Photos Section

General Sir Douglas Haig, commander of the British army, was optimistic and bullish, and believed his Third and Fourth Armies would punch through the German lines on the first day of the Somme, bringing a return to mobile warfare. His attack was focused on the strongest portion of the German Second Army’s positions and was significantly under-resourced. (Te Papa)

General-der-Infanterie Erich von Falkenhayn, the German Chief of General Staff, Supreme Army Command, was focused on operations at Verdun and Galicia, and believed his Second Army had the resources to ward off an Anglo-French offensive on the Somme. Falkenhayn underestimated the French component, however, and was forced to rethink his Somme strategy going forward. (Period postcard)

Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Rawlinson, commanding Fourth Army, preferred a step-by-step approach to operations on the Somme and doubted a breakthrough would be achieved on the offensive’s first day. (Imperial War Museum [IWM])

General-der-Infanterie Fritz von Below, commanding the under-resourced German Second Army, expected a strong British offensive north of the Somme, but underestimated the strength of the French attack. (Author’s collection)

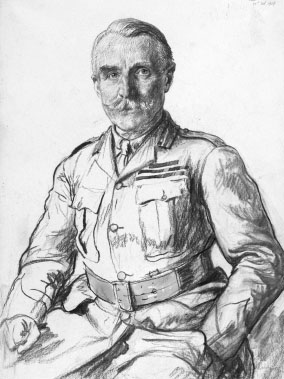

Lieutenant-General Sir Edmund Allenby, commanding Third Army, went along with plans for an operation at Gommecourt salient to divert German artillery and infantry reserves, despite his initial reservations. (IWM)

Generalleutnant Hermann von Stein, commanding the German XIV Reserve Corps, expected the Allied offensive, but the outcome of battle revealed his failure to create defences of uniform strength north of the River Somme. (Period postcard)

Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas D’Oyly Snow did not understand the difference between diversions and feints, which explains why his VII Corps became a magnet for German machinegun and artillery fire at Gommecourt. (IWM)

Generalleutnant Richard Freiherr von Süsskind-Schwendi was the aloof and ruthless commander of 2nd Guards Reserve Division at Gommecourt, where his men annihilated VII Corps. (Author’s collection)

Lieutenant-General Sir Aylmer Hunter-Weston condemned his VIII Corps to disaster around Serre and Beaumont Hamel after bungling his artillery plan and the timing of the Hawthorn Ridge mine blast prior to battle. (IWM)

Generalleutnant Karl von Borries oversaw his 52nd Infantry Division’s construction of bespoke and robust defences between Gommecourt and Serre, which defeated VII and VIII Corps. (Courtesy of Infantry Regiment 170)

Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas Morland’s X Corps mostly failed bloodily because of his linear thinking around Thiepval, while dithered command decisions on his part resulted in missed opportunities at Schwaben Redoubt. (IWM)

Generalleutnant Franz Freiherr von Soden drove his 26th Reserve Division hard to develop a lethal network of defensive killing zones between Serre and Ovillers, which mostly repulsed III, VIII and X Corps’ attacks. (Courtesy of 26th Reserve Division)

Lieutenant-General Sir William Pulteney was guileless and ignorant of the strength of the German defences his III Corps faced at Ovillers and La Boisselle, which was why it failed so tragically in a maelstrom of machine-gun fire. (IWM)

Generalleutnant Ferdinand von Hahn, the head of 28th Reserve Division, successfully defended La Boisselle against III Corps, but lesser-quality positions at Fricourt and Mametz saw both lost to XV Corps by 2 July 1916. (Courtesy of Reserve Infantry Regiment 221)

Lieutenant-General Sir Walter Congreve, VC, was professionally minded and prepared, which was why his XIII Corps triumphed over German positions at Montauban. He focused on consolidating gains rather than exploiting them. (IWM)

Generalleutnant Martin Châles de Beaulieu’s hands-off command of 12th Infantry Division between Montauban and the River Somme condemned his men to failure against the British XIII Corps and French XX Corps. (Courtesy of Infantry Regiment 23)

Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Horne had a ruthless, nimble mind and produced partial victory by his XV Corps at Fricourt and Mametz, but his opportunist streak caused unnecessary casualties when he attempted to force Fricourt’s early capture. (IWM)

General Sir Hubert Gough was the bullish, attack-minded commander of Reserve Army, which was to come into play after German lines were breached. He was to be frustrated throughout the opening day of the Somme. (Te Papa)

Officers and men of 15th West Yorkshires take a break from practising trench digging in England. This battalion was destroyed by German machine-gun fire near Serre on 1 July 1916. (Peter Smith Collection)

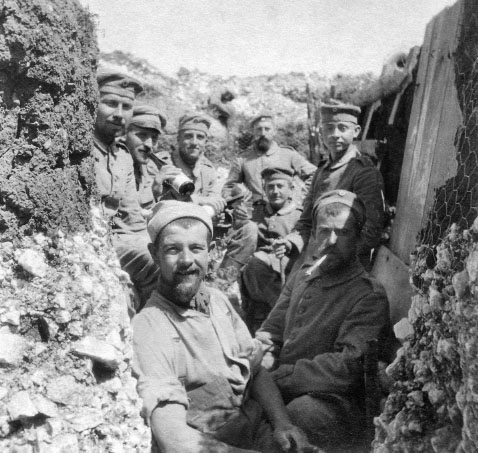

Württemberg soldiers of all ages stop work for a cigarette and a crafty swig of wine in a trench near Beaucourt, in the River Ancre valley. (Author’s collection)

Tin hats, puttees, gas masks and Lee Enfields — soldiers from a York and Lancasters’ battalion scrubbed up well for a behind-the-lines studio photograph to be sent home to their families in England. (Peter Smith Collection)

‘You will certainly be a bit miffed as I didn’t send you any news, but I totally forgot,’ wrote Ersatz-Reservist August Stegmaier, Infantry Regiment 180, from the trenches at Serre. Stegmaier, pictured at top left, was killed on 28 September 1916. (Author’s collection)

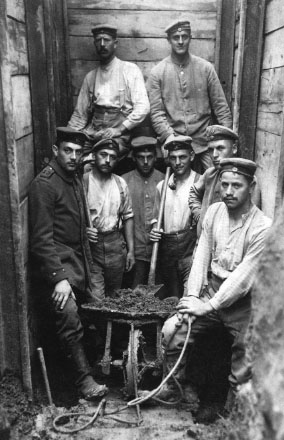

Dig, dig, dig! Württemberg soldiers from Pioneer Battalion 13 take a breather from excavating what appears to be either a deep dugout to withstand British shellfire or a mine chamber under no-man’s-land. (Author’s collection)

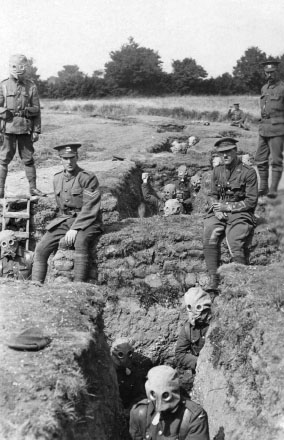

Gas-mask-wearing British soldiers rehearse the job of clearing a mock German trench under the watchful eye of trainers in England. Fist-sized beanbags were used as substitutes for hand grenades during training. (Peter Smith Collection)

‘I was terribly worried,’ wrote Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Collins, 17th (Northern) Division headquarters, of the 10th West Yorkshires’ role on the first day of the Somme. The battalion suffered galling casualties advancing from trenches like these near Fricourt. (IWM)

‘The air reverberates to the drum of our cannonade,’ wrote Major James Jack, 2nd Scottish Rifles, of British shellfire on enemy positions. Pictured is a 9.2-inch gun immediately after belting out its high-explosive payload sometime on 1 July 1916. (IWM)

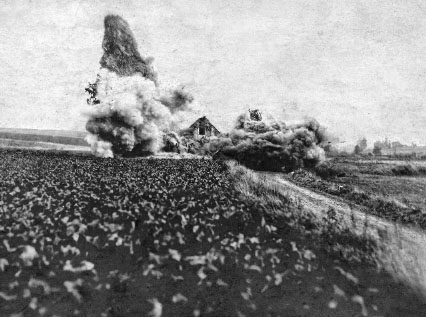

‘What would it be like to receive a direct hit from a ship’s 30-centimetre gun?’ pondered Fahrer Otto Maute, Infantry Regiment 180. The road shown here being struck by a high-explosive shell, near Miraumont in June 1916, was on Maute’s wagon route. (Author’s collection)

‘Down there we sit and read and write by the light of a candle,’ said Unteroffizier Wilhelm Munz, Reserve Infantry Regiment 119. These Württemberg artillerymen are holed up in a shell-proof dugout, and using a salvaged house door as a table. (Author’s collection)

This well-camouflaged Bavarian field gun at Montauban may have gone unseen by the probing eyes of Royal Flying Corps observers, but its flimsy shelter did nothing to protect it from searching British counter-battery fire. (Author’s collection)

‘The earth rose in the air to the height of hundreds of feet,’ wrote Lieutenant Geoffrey Malins, who filmed the massive Hawthorn Ridge mine blast. Its detonation at 7.20 a.m., 10 minutes before VIII Corps’ advance was due to begin, alerted German soldiers that they were about to be attacked. (IWM)

‘The field was white, as if it had snowed,’ wrote Leutnant-der-Reserve Matthaus Gerster, Reserve Infantry Regiment 119, of the Hawthorn Ridge mine explosion. It was no different at La Boisselle, as evidenced by the chalkstone jaws and spoil of the huge Y-Sap crater. (IWM)

‘How feeble and tiny they looked in that ghastly reek,’ thought Second-Lieutenant William Tullock, 53rd Machine-Gun Company, of British infantry advancing on the German front line near Montauban behind great spurts of liquid fire from Livens flame projectors. (IWM)

‘My heart seemed to stop; now comes the end,’ wrote Leutnant-der-Reserve Friedrich Kassel, Reserve Infantry Regiment 99, of a British shell that landed above his dugout. Pictured are Bavarian gunners in their dugout at Montauban early in the British preparatory bombardment. (Author’s collection)

‘Anyway, it was time to go over,’ wrote Lance-Corporal Archibald Turner, 10th Lincolns. Equipment-laden infantrymen of 34th Division trudge slowly towards the tornado of German machine-gun and artillery fire near La Boisselle. (IWM)

Mash Valley’s killing zone was designed by Hauptmann Otto Wagener, RIR110. (IWM; courtesy of Reserve Infantry Regiment 110)

‘I wanted to find out what they were looking for,’ noted a perplexed Private Lew Shaugnessy, 27th Northumberland Fusiliers, of soldiers he saw going to ground on the La Boisselle no-man’s-land. Many of them were dead or wounded, or seeking respite from the German fusillade. (IWM)

‘Never in the war have I experienced a more devastating effect of our fire,’ stated Vizefeldwebel Theodor Laasch, Reserve Infantry Regiment 110 (RIR110). He was writing about Mash Valley, where British dead lay thickly (top). Mash Valley’s killing zone was designed by Hauptmann Otto Wagener, RIR110 (above). (IWM; courtesy of Reserve Infantry Regiment 110)

A Bavarian machine-gun team set up for business on a shellfire-hammered trench parapet, having raced up from their dugout beneath. Even heavily damaged positions were defensible, as this photo taken later in the summer of 1916 illustrates. (Author’s collection)

Barbed-wire pickets and fields of fire — a German view of no-man’s-land through a metal observer’s shield, said to have been taken near La Boisselle. British infantry relied on their artillery sweeping away the wire and at least suppressing enemy resistance. (Author’s collection)

‘By thunder Herr Feldwebel, I am firing!’ yelled a Baden soldier to Vizefeldwebel Theodor Laasch, Reserve Infantry Regiment 110. Here soldiers of Laasch’s regiment draw bead on British infantry stranded in no-man’s-land near La Boisselle on 1 July 1916. (Courtesy of Reserve Infantry Regiment 110)

‘If the British had made a fresh attack we could not have held our position,’ wrote Unteroffizier Paul Scheytt, Reserve Infantry Regiment 109. Soldiers of 7th Queen’s and 7th Buffs pause on the Mametz–Montauban road on 1 July 1916, before their final attack on Montauban Alley. (IWM)

‘God only knows how any of us got there, but we did,’ recalled Private Clifford Barden, 7th Royal West Kents, of reaching his battalion’s objective, Montauban Alley. Soldiers of 55th Brigade (above) began consolidating that trench for defence soon after its capture. (IWM)

‘I considered further sacrifice to be pointless,’ said Oberst Jakob Leibrock, commander of Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 16, whose headquarters’ dugout was hidden among the ruins of La Briqueterie (above), a brickworks east of Montauban. He and his staff soon surrendered. (IWM)

‘It was pure bloody murder,’ remembered Private Peter Smith, 1st Borders. This unidentified British soldier, found dead in the trenches near Montauban, is slumped on his rifle and wearing a haversack of hand grenades. (IWM)

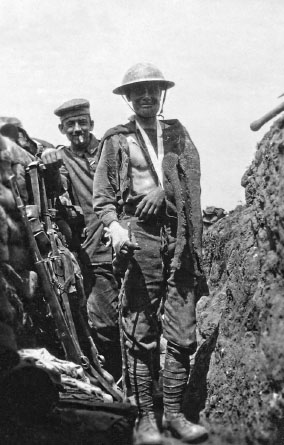

‘Hands up, you fool!’ A dishevelled and wounded British prisoner, said to have been nabbed during the brutal close-quarter Heidenkopf fighting, manages a weary smile as his triumphant captor from Württemberg looks on. (Author’s collection)

‘I cannot now see the features in a person’s face,’ wrote Private Sidney Smith, 1/5th Sherwood Foresters, of being wounded on 1 July 1916. Here, a badly injured British soldier, with his eyes crudely bandaged, lies in the German trenches at Gommecourt. (Author’s collection)

‘We will have lunch in the German trenches,’ said Lieutenant Billy Goodwin, 8th York and Lancasters, to one of his soldiers just before battle. The Corpus Christi College graduate was highly regarded by his platoon. He died snared in German wire in Nab Valley on 1 July 1916. The 23-year-old, who liked golf, tennis and motorcycles, is buried at Blighty Valley Cemetery. (Liddle Collection, University of Leeds)

‘It’s a shame the holiday came to an end so quickly,’ wrote Reservist Friedrich Bauer, Infantry Regiment 180, after returning to the Somme trenches from leave. The 25-year-old, from Rudersberg in Württemberg, had been an orchard worker and liked to sing on his way to and from work. He was killed on 3 July 1916 at Ovillers and has no known grave. (Author’s collection)