Chapter Six

The Parade:

Marching Toward Freedom

We’re marching on to freedom land, we’re marching on to freedom land.

God’s our strength from day to day, as we walk the narrow way.

We’re going forward, we’re going forward.

One day we’re going to be free.

— “We’re Marching on to Freedom Land,” Carlton Reese,

Voices of the Civil Rights Movement: Black American Freedom Songs

1960–1966, Smithsonian Folkways, 1997.

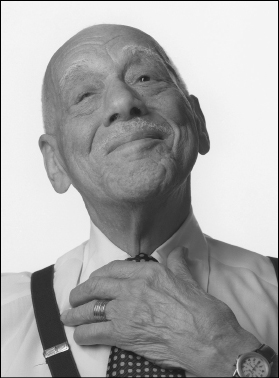

Spotlight on ...

James Lewis, like Ray’s great-grandparents on his father’s side and grandparents on his mother’s side, was a former slave who escaped to Canada. He operated a business as a barber and hairdresser in Simcoe, Ontario. Ray Lewis was born in Hamilton in 1910, and in the 1932 summer Olympics he became the first African-Canadian athlete to win an Olympic medal for the 4 x 100 relay. Ray Lewis was a special guest at Emancipation Day in Windsor in the 1930s. In honour of his achievements and his ability to overcome racial discrimination, Ray was awarded the Order of Canada in 2001. A Hamilton school was named after him in 2005, and in 2010 he was inducted into the Hamilton Sports Hall of Fame.

The parade was the main attraction of most Emancipation Day celebrations. Parades were very popular in North American cities during the 1800s and 1900s and remains so today. For Emancipation Day, street processions became a significant feature of the annual tradition to commemorate the end of the enslavement of Africans, to mark the anniversary of the abolition of slavery, and to celebrate freedom. What made the parades so appealing, drawing hundreds and even thousands of people annually? How were they organized and structured to appeal to the masses year after year? What did the crowds see and hear?

Raymond Gray Lewis often ran alongside railway tracks to practise for track and field while he worked as a porter. He was given the nickname “Rapid Ray” because of his ability to run fast.

Courtesy of the Hamilton Spectator.

Parade Marshals

The ceremonial title of grand marshal was given to a special guest or dignitary, often a recognized community leader, and this person was chosen to lead the parade. In the nineteenth century, grand marshals, mounted on horses, led the parade of marchers, carriages, and floats. They were also the official greeters for those arriving from out of town by steamer or train and were responsible for ensuring an orderly public demonstration.

Spotlight on ...

Charles Peyton Lucas was a self-emancipated man from Virginia. He ran away in 1841 in his early twenties and eventually settled in Toronto by 1852, after making his way north to protect his family from the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law. As a teenager, Charles was hired out as an apprentice to a blacksmith and trained in that skilled trade. He went on to become a blacksmith in Toronto and was noted as an exceptional shoer of horses. Charles, his wife Catherine, and their three children lived on Centre Street in downtown Toronto, near Osgoode Hall, which had a large population of fugitive slaves. His children attended the neighbourhood school. Always a very active supporter of the Black community, he was a marshal in an Emancipation Day parade in Elmira, New York, in 1850. Charles died in Toronto in January 1870 at the age of fifty.

Moses Brantford Jr. was appointed the grand marshal for the parade in Amherstburg in 1894, as shown in the image on the cover of this book. James Lewis, the maternal grandfather of Hamilton-born track athlete and railway porter Ray Lewis, was chosen to be the grand marshal three times: 1884, 1888, and 1893, all of these in Hamilton.

Mounted assistant marshals helped to guide the procession and ensure it ran smoothly, directing the line of the march as it wound its way through the main streets. Charles Peyton Lucas, a blacksmith and a former slave from Virginia, was the assistant marshal of the 1854 August First parade in Toronto. Later on in the twentieth century, with the introduction of the automobile, parade marshals led marchers in decorated convertibles. As another example, Windsor’s 1954 parade was marshalled by a seven-man motorcycle squad.

Marching Bands

A uniformed musical band followed the Grand Marshal in the procession. Hired bands provided lively entertainment with their horns, drums, cornets, trombones, clarinets, violins, guitars, and banjos. Most of these regimental marching bands were made up of volunteer militiamen and war veterans. The former soldiers who played in August First parades were exceptionally artistic because it was common for Black men to be the musicians in most military units.

Military bands regulated everyday life for soldiers in service. They gave signals or provided coded orders during battle, lifted the spirits of soldiers during wartime, and performed tattoos — outdoor military exercises that were evening entertainment for troops. The Weaver Band from Chatham, named after politician and business owner Henry Weaver, was led by drum major John Freeman at Windsor’s 1895 parade. The Excelsior Band of Chatham, under captain and drum major Jack Richards, was one of the marching bands in the 1883 Toronto procession, and the Sons of Union from Detroit were invited to march in the parade in Windsor in 1852.

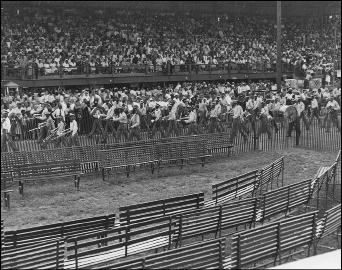

Celebrants packed the grandstand at Jackson Park to watch the spectacular parade enter the grounds.

Courtesy of the E. Andrea Shreve Moore Collection, Essex County Black Historical Research Society.

Spotlight on ...

Henry Weaver escaped slavery in America and settled in Chatham with his wife, Annie. They purchased a building, where Henry owned and operated a butcher shop downstairs, while his wife ran a small inn upstairs. She rented rooms to Black travellers who were denied accommodations at local White-owned hotels because of their race. Henry was the first Black man elected as a city councillor in Chatham, serving from 1891 to 1893 and again from 1895 to 1898. He was also very involved in the Black Masonic lodges of the city. The Weaver Band was named in recognition of his community achievements and his personal support for the band.

The tunes played by the bands were a musical expression of Blacks’ heartfelt loyalty to Britain and the ideas of national and cultural identity they held. Bands played patriotic pieces such as “God Save the Queen,” “The Star Spangled Banner,” and later “O Canada.” They also played popular folk songs and good-time music like “When the Saints Go Marching In,” anti-slavery songs like “Get off the Track,” and marching songs like “John Brown’s Body.” There were woodwind, string, brass, or fife and drum bands. Parade-goers listened to the Harrow Brass Band of Essex County play in Amherstburg in 1894 and the Union Brass Band from Hamilton in Chatham in 1874. Scott’s Cornet Band and Reed Brass Band from Buffalo played in Brantford in 1894 and Cleveland’s Drum and Bugle Corps marched in 1970 in Windsor.

Along with regimental bands, other musical ensembles that marched in Emancipation Day processions during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries included police bands, community band groups, professional troupes, concert bands, and drill teams from Ontario and the United States. John W. “Jack” Johnson was an exceptionally talented bandleader. The London, Ontario, native moved to Michigan and founded the Detroit City Band in the early 1880s. He returned to his hometown to lead the Forest City Band at the end of that decade. Local musical bands such as the Windsor City Band, the Optimists Youth Band, and the South Windsor Lions were also regular players.

The North Buxton Maple Leaf Marching Band. Ira. T Shadd offered music classes to families in North Buxton and once the student’s skills developed, they became members of the band.

Courtesy of the Buxton National Historic Site & Museum.

Freedom Through Music

The Weeks Band from Thorold (near Niagara Falls), the Chatham City Band, the Eureka Colored Band from Niagara, the Forest City Band of London, the Detroit City Band, and the Mount Pavement Band from Detroit were just a few of the hundreds of bands that performed in Emancipation Day parades across Ontario in the 1800s.

The well-known North Buxton Maple Leaf Band was formed by Ira T. Shadd in 1955. They participated in Emancipation Day parades in Windsor, beginning in 1956 and regularly after that. Historian, author, and researcher Adrienne Shadd was a majorette in the North Buxton Maple Leaf Band in the 1960s. She recalls that their most notable marching song was “The Maple Leaf Forever,” recently revived by Michael Bublé at the closing ceremonies of the 2010 Winter Olympics, in Vancouver.

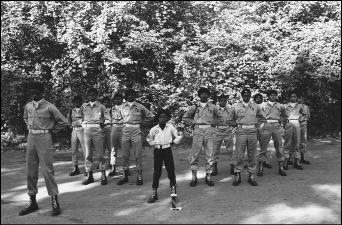

African-American drill bands performed elaborate manoeuvres based on military drills as part of Windsor’s parade. One such group was the popular French Dukes Precision Drill Team from Ann Arbor, Michigan, who performed annually between 1966 and 1970. People who attended Emancipation Day celebrations in Windsor as a child during the 1950s and 1960s identify the drill teams as their most memorable recollection. One person states, “The drill units were replete in military uniform and toting rifles. Their drills and routines were so rhythmic and exact.”[1] Another individual recalls, “I especially remember the military style bands with the young men and women performing the most exquisite precision drill marches. The French Dukes from Michigan were my favourite. They routinely won the Emancipation Day contest for the best drill team.”[2]

Walter Perry, organizer of Windsor’s Greatest Freedom Show on Earth, scouted and invited talented Ohio, Michigan, and Indiana singers and bands to participate in Emancipation Day festivities. The talents of drill teams and baton twirlers were showcased when they marched. Majorettes, which were young female dancers, accompanied marching bands beginning in the mid-1950s. The majorettes twirled batons skilfully while performing choreographed movements.

The French Dukes Precision Drill Team were regular winners for the best drill team at Emancipation Day celebrations in Windsor during the 1960s, due to their exceptional talent. Formed in 1962, the group went on to win every state and national competition they entered.

From theAnn Arbor News, September 8, 1968. Courtesy of the Herald Company, Inc.

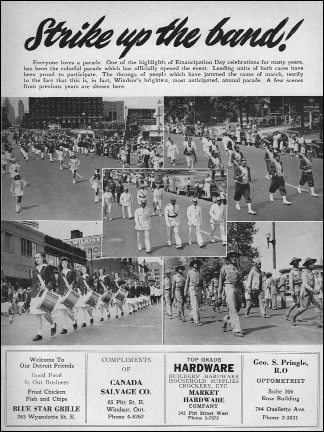

Several snapshots of Windsor’s Emancipation Day parade in 1947 that highlight the diversity of the marching bands.

Courtesy of the E. Andrea Shreve Moore Collection, Essex County Black Historical Research Society.

Spotlight on ...

The French Dukes Precision Drill Team was sponsored by the junior auxiliary of the Elks-Pratt Lodge No. 322, Improved Benevolent and Protective Order of the Elks of the World. The twenty-five Black youth, ages fifteen to eighteen, were selected to march in the 1969 inaugural parade for Richard Nixon in Washington, D.C.

A variety of other ethnic marching bands participated in the August First parades. Several First Nations and European bands have performed throughout the celebration’s history. Aboriginal bands included the Grand River Band, which performed in 1875 in Brantford. The 37th Haldimand Rifles, a regimental marching band made up of former soldiers from the Six Nations Reserve, played in Woodstock in 1898 and in Brantford in 1912. The Oshweken Indian Cornet Band marched in Hamilton’s 1893 parade, and the Muncey (also spelled Munsee) Indian Band took part in Emancipation Day commemorations in London in 1895. White bands included the Toronto Victoria Band of the Orange Order, a fraternal organization of Protestant men of Scottish or North Irish heritage. They marched in St. Catharines in 1891 and in Brantford in 1903.

African Canadian and Native bands were also invited to play in other civic parades, including Victoria Day, Dominion Day, and Labour Day parades. They performed at public events that celebrated the British monarchy, such as royal visits and Queen Victoria’s Golden and Diamond Jubilees in 1887 and 1897. These bands often played at agricultural shows across the province, and these performances were huge social events. The Canadian National Exhibition (CNE) was an agricultural show that featured farm animals, equipment, and recreational activities. They provided musical entertainment at political dinners, public anniversaries, opening ceremonies, and other public observations. Black and Native bands would take part in funeral processions for community leaders and elected officials. These bands also held annual tattoos that were widely attended.

Emancipation Day was definitely a multicultural affair. Although the majority of participants were of African heritage, people of different races not only marched alongside one another, but also interacted at various junctures of this huge exhibition.

Marchers

Marchers in August First parades represented various social and community organizations. Following behind the bands and veteran military units were numerous chapters of Black Masonic lodges: Prince Hall Grand Lodge of the Province of Ontario, the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows, and the Knights of Pythias. These fraternal orders were also involved in the organization of Emancipation Day celebrations, including St. John Lodge No. 9 of Chatham, Eureka Lodge No. 20 of Toronto, and Victoria Lodge No. 2 in St. Catharines, along with the groups mentioned in Chapter 3. The lodge’s lady auxiliary groups were made up of the wives and daughters of male members. They sponsored carriages and cars in August First processions. The Women of the Order the Eastern Star, the Household of Ruth, the Daughters of Samaria, and the Star of Calanthe are some of the longstanding African-Canadian female organizations that were active in the community.

Literary groups, cultural clubs, benevolent societies, political groups, music and dance ensembles, school children, and African-Canadian temperance societies also marched in the parade. During the 1860s, there was a growing movement with settlers of both races to abstain from drinking alcohol, because they believed that it led to the ruin of individuals and society. The Temperance Society of Amherstburg and the Sons of Temperance in Hamilton were part of the trend to reduce the harmful impact of alcohol on the Black community.

One approach to improving the conditions of the community was to establish educational support groups such as the Chatham Literary and Debating Society and the Hour-A-Day Study Club in Windsor. The Chatham Literary and Debating Society, also called the Chatham Lyceum, was formed in 1872 by grocer Ezekiel C. Cooper and other board members to offer lectures and debates. Beginning in 1934, the women of the Hour-A-Day Study Club in Windsor dedicated sixty-minutes a day — hence the name — to expanding their intellect. They also encouraged childhood literacy by giving books to mothers with babies.

Wordplay

A benevolent society is a voluntary organization that is established for the purpose of charity. They plan activities and events to raise money for a particular cause.

Associations that provided help to incoming fugitives included the Provincial Union Association, the Victorian Reform Benevolent Society, and various abolitionist societies in Ontario and Nova Scotia. As refugees from American slavery were a major concern during the mid-1800s, a considerable number of support groups arose. The Brotherly Union Society in Hamilton was a benevolent society. It was formed in 1862 by several community leaders to provide financial assistance to those in need. The Ladies Auxiliary of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, Pullman Division, focused on educational programs and scholarships for young people from the 1940s through to 1957. Many organizations had a number of chapters across the province or the country, like the Universal Negro Improvement Association in Toronto, Montreal, and Nova Scotia (in Sydney, Halifax, and Glace Bay). African Canadians were frequently members of more than one organization. Community organizations had a strong presence in Emancipation Day parades.

Male and female marchers dressed up in coloured costumes, elaborate dress, and full regalia or uniforms. Former soldiers wore their uniforms with pride while Black Masons donned their ceremonial dress. This was often vividly described in newspapers covering the events. One such account notes, “In line were the colored Knights Templars, in plumed helmets and drawn swords....”[3] Another describes a group of six Black freemasons masons “… dressed in gowns like a beadle’s, three-cornered cocked hats with feathers, and white pants (excepting one carrying a sword whose costume was partly scarlet).”[4] When the female members of the Household of Ruth performed drills in Hamilton in 1884, they were described as looking stunning in their “regalia of gold braid and black velvet, with tiaras and crowns of glittering tinsel.”[5]

A poster advertising the 1939 Emancipation Day festivities in Windsor.

Courtesy of the E. Andrea Shreve Moore Collection, Essex County Black Historical Research Society.

Parade Symbols

Many symbols have been part of August First parades. Participants proudly waved flags: the Union Jack, the Stars and Stripes of the United States, and later the Canadian flag. Most people carried banners and signs with political and anti-slavery messages, such as “God, humanity, the Queen, and a free country,” “Sons of England,” and “Am I not a man and a brother?” which means that God made all men from one blood. Banners and sashes identified the assorted groups of marchers as they passed. The emblems of Black Masonic orders and other participating organizations were displayed with confidence, and other symbols representing Britain and America, such as John Bull and Uncle Sam — the respective icons of each country’s patriotism — were much in evidence.

Freedom, history, and remembrance have been regular themes since 1834. Pamphlets, flyers, leaflets, and posters were distributed or posted along parade routes to encourage people to participate in community initiatives that addressed specific issues of concern to African Canadians once Emancipation Day celebrations were over, issues such as the abolition of American slavery, segregated schools in Ontario, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick, or the other numerous concerns during the Civil Rights Era. In 1964 Toronto marchers carried a placard with the words “Canada needs racial equality, too!”

Programme booklets were another form of text used to communicate with Emancipation Day visitors. They were distributed or sold at various Emancipation Day venues, local businesses, and community organizations. First published in Windsor in 1948, the Emancipation Day event magazine Progress: An Official Record of the Achievements of the Coloured Race, printed annual issues that contained articles and interviews highlighting the achievements of people of African descent, photos and images of Blacks, advertisements for Black and White owned businesses, and the weekend programme of Emancipation Day events.

Parade Floats

Spotlight on ...

James Mink earned his riches by operating Toronto’s largest livery stable, on Adelaide Street, and a hotel called the Mansion Inn, at the corner of Richmond and York streets. James and his brother George (the sons of freedom seekers) owned stage coach companies that transported mail and federal prisoners between Toronto and Kingston. James also provided his service to the mayor and city councillors of Toronto.

In an unfortunate turn of events, James gave his daughter’s hand in marriage to a White man who was from Yorkshire in northern England, who then took her to the United States under the guise of going on a honeymoon and sold her into slavery. It took James large amounts of time and money to purchase his daughter’s freedom and bring her back to Canada.

August First street processions included very popular float entries that honoured the occasion. Horse-drawn carriages, wagons, and later automobiles well-decorated with streamers, ribbons, flags, and flowers were pulled or driven through the main streets: “One feature of the morning procession was quite impressive — that of a car, beautifully decorated with flowers, etc., forming a canopy, under which were seated, we should judge, at least thirty little girls tastefully arrayed in white, and with wreaths of flowers on their heads.”[6] In London in 1896, seventeen out of twenty carriages carried women, two of them were White.

It would take days, weeks, or even months to design, create, and build floats. Throughout the year, fundraisers were held and time, money, and materials were donated to make marvellous floats. They were used to communicate various messages such as the death of slavery. Different effigies, which are crafted representations of a disliked person or political idea, which represented slavery, were included in parades, and their destruction symbolized the abolition of slavery. In Hamilton in 1859, men of the Masonic lodge Sons of Uriah carried axes as a symbol of the downfall of the slave master. Floats also depicted topics of historical significance and promoted pride. Carriages and convertible cars carried dignitaries, community leaders, and guests of honour. Open-back trucks were used to transport children in the parade. Motorcades, a procession of vehicles, were another prominent aspect of the parade.

Emancipation Day parades often left a lasting mark on the viewer. In the 1850s, the daughter of Canadian author Susannah Moodie, Agnes Chamberlin, who was then in her early twenties, recalled seeing James Mink, one of the wealthiest Black people in Toronto, in the first carriage of the parade, being drawn by eight horses.

The Spectators

CELEBRATION

THE Abolition Society intend to celebrate the Anniversary of the Abolition of Slavery in the British Dominions, on the First of August next, by a PICNIC, &c., to take place at Belmont. The Committee of Management therefore request the attendance of all the colored people of Halifax and the vicinity, and all the Friends of Liberty and Freedom. They would likewise appeal to the Ladies and Gentlemen of Halifax for permission to the colored servants in their employ, to hold this one day of rejoicing as a holiday.

A procession will start at 9 o’clock from the African School House, and proceed to Church, where service will commence at 10 o’clock, after which they will proceed to Belmont, and pass the remainder of the day in healthful and innocent enjoyments. Tickets to be obtained at the gate. Entrance 77. By order of the President.

THOMAS JONHNSON.

July 17. Secretary.

— British Colonist (Halifax), July 19, 1851

Parades were an opportunity to make a grand public show. The amount of observers lining the parade routes ranged from dozens to hundreds, sometimes as many as ten deep. People also watched parades from rooftops and second- and third-story windows. The large audiences included spectators from near and far, from all kinds of backgrounds.

Spectators were given a visual treat. Gestures and shouts were exchanged as the procession passed, and goodies were thrown to the crowds. The role of the parade observer was important — certainly the demonstration was put on to entertain them, but the parade also served to educate them for a lifetime and to motivate them to take action in their communities in the days that would follow.

To ensure a good turnout, the public had to be informed of the parade well in advance. Emancipation Day committees placed ads in local newspapers and distributed flyers weeks before the actual events. One reason for this was to ensure that Black workers could get the day off if August First fell on a weekday. In one instance, the African Abolition Society, which was sponsoring Emancipation Day in Halifax in 1851, requested — right in their advertisement — that White employers give their Black employees the day off.

Parades varied in scale and duration, from small processions that lasted for a brief time to massive demonstrations that lasted for two hours. Emancipation Day processions were a public occasion filled with pomp, ceremony, pageantry, and carnival motifs. It was a visual experience, and generally the most anticipated event of Emancipation Day.

Together, the various elements of the parades told stories of resistance, victory, freedom, and achievement, as well as the importance of memorializing African ancestors, Black history, and African-Canadian customs. The parade also served as a way to interact with the larger Black community and mainstream society. It reflected the structure of the local Black community and mirrored the values community members held, such as equality and justice. The organizers, marchers, and many of the people that watched the affair were the ones who assisted and contributed to the development of the Black community. The yearly public demonstration was also about making a political statement on issues of concern, such as racial discrimination in employment, housing, public businesses, and the presence of segregated schools, but it also served to mobilize community members around these matters. The other important point made by processions was that African Canadians were capable of conducting themselves in an orderly, well-behaved, and civilized fashion, debunking many myths and stereotypes. Some blatant misconceptions about Blacks existed into the twentieth century: that they were lazy, uncivilized, rowdy, and ill-mannered.

August First parades were also a public display of Black solidarity, strengthened with the inclusion of multiple generations. Additionally, the marches were a place to publically challenge the White dominance of the other days of the year. Purposely, Blacks occupied the most prominent streets of the town or city, areas that in some cases would otherwise not be accessible to them because of their race. Lastly, the processions symbolized racial pride.

Caribana

Caribana, the Trinidadian-style carnival parade, has roots in Emancipation Day commemorations in the West Indies. Since 1967, the vibrant festival has attracted spectators of all cultural backgrounds, with a large number of them being African Americans who go to Toronto to “jump up.” Held in Toronto, Caribana has replaced Emancipation Day as the major Black event in the city.

A steel pan band playing on a parade float for Caribana. The steel pan is a percussion instrument. It originated in Trinidad and Tobago in the 1930s when the tops of petroleum oil drums were cut and hammered out to make different musical notes.

Courtesy of Hameed Shaqq.

The first parade route followed Yonge Street and ended at Nathan Phillips Square, then it moved to University Avenue in 1970 and remained there until 1991, when it was relocated to Lakeshore Boulevard. Some of the islands represented are Trinidad, Jamaica, Barbados, and the Bahamas. The South American country of Brazil is also included. Parades consist of hours of masquerade bands, vibrant costumes, and steel bands. The music includes calypso, soca, reggae, R&B, and hip hop. Thousands of people enjoy West-Indian music, art, and food over the civic holiday long weekend. Other Caribana activities include competitions, boat cruises, dances, and concerts. The festival is a big financial boost to Toronto, bringing almost five hundred million dollars into the economy.[7]

Several junior Caribana parades were introduced in Toronto in the 1990s to provide an opportunity for youth of all backgrounds to connect to Caribbean culture through music, costume, and dance. They traditionally take place one week before the main Caribana parade.

All Dressed up with Somewhere to Go

The grandeur of Emancipation Day required that men and women dress their best. How they looked and presented themselves was important. Wearing their finest clothes, their “Sunday Best,” was an expression of freedom, because enslaved Blacks had not been permitted to wear certain clothes. The slave master provided clothing, usually once a year. It was often old, tired hand-me-downs or clothing made from coarse fabric such as burlap, and sometimes shoes were not included. At Emancipation Day events, the dress was often formal and glamorous. Men and women chose to wear elaborate and extravagant suits and dresses to symbolize their status as free persons and to express themselves in as masculine or feminine a way as they desired.

Processionists wore sophisticated uniforms and ornate costumes. Celebrants dressed in holiday garb. They had their outfits specially made, or purchased them in special shops. The local newspapers provided detailed accounts on how Emancipation Day excursionists were dressed. In 1859 the Hamilton Spectator noted, “... our colored lady friends displayed, yesterday, the most effulgent robes, the most splendid silks and satins, that can be seen in a day’s shopping.”[8] In 1907 in Ingersoll, a town in Oxford County in southwestern Ontario, women wore “fine hooped skirts” and men dressed in “white vests, full dress coat, peg-top trousers, and white neck-tie with elaborate stand-up collars.”[9] The Brantford Weekly Expositor described how ladies looked lovely from their feet to their heads: “Young women robed in floor sweeping gowns of salmon pink and royal blue raise delicate gloved hands, to their coiffed ringlets.”[10] The men were portrayed as wearing “black frock coats, light pants, white vests, and black plug hats.”[11] Their exceptionally neat dressing during the mid to late nineteenth century showed the civility of Blacks and reflected their elevated social standing.

Emancipation Day celebrations received media coverage in newspapers across the country.

Courtesy of theChatham Daily News.

In the twentieth century, donning the latest fashion during August First festivities remained popular. During the 1930s, ladies dressed in lace-trimmed dresses, butterfly skirts, and sailor suits, while gentlemen looked sharp in zoot suits. African Canadians continued to attend Emancipation Day in the 1940s and 1950s, well-dressed in peep toe shoes, gloves, puppy skirts,

Beehive hairstyles, a-line skirts, empire-line dresses, slim-fit pants, and Mary Jane shoes with bobby socks. Men sported flannel suits and penny loafers.

The 1960s saw an evolution of fashion that reflected the revolutionary sentiments and racial pride of the Civil Rights Movement and an emerging middle class and urban culture. Ladies wore mini-skirts, psychedelic prints, highlighter colours, pillbox hats, sleeveless shift dresses, skinny jeans, pleated skirts, and patent leather or vinyl shoes and handbags. Men wore buffalo plaid shirts and unisex fashions, such as bell-bottom jeans, blue jeans, and dashikis. Both genders widely embraced what the afro symbolized — pride in one’s African identity. In the following decades, celebrants continued to wear trendy but less formal clothing. The clothing reflected the social attitudes of the time, as more liberal and inclusive ideals of youth led to different styles of dress.

Every year African Canadians were marching toward freedom, celebrating the freedom that was achieved so far, and taking steps toward the freedom yet to be fulfilled. The involvement of youth in the most anticipated event of Emancipation Day — the parade — ensured the longevity of the tradition. Emancipation Day parades were important, effective in the public expression of and petition for freedom.