Chapter Eight

Oral Culture and Emancipation Day:

Talking about Freedom

Talking about freedom, talking about freedom,

we will fight for the right to live in freedom.

— “Freedom,” Paul McCartney, Driving Rain, Capital Records, 2001.

Speeches were an integral component of Emancipation Day commemorations. In the 1800s, speeches were an important form of education because of the low levels of literacy. Few people could read or write, especially among formerly enslaved Africans who had been denied access to a formal education. An oral culture developed, which was essential for communicating and preserving history and cultural values, as well as bringing public awareness to pertinent issues of the time. Speeches were also a form of entertainment and drew on the importance of the oral tradition in African culture. While discussing serious topics, humour was incorporated as well as aspects of church sermons. The “call and response” was utilized to hold the attention of the audience.

A spectrum of speakers were invited to talk at various venues, including churches, parks, mechanic institutes, and community and private halls were filled with individuals both Black and White, male and female, from assorted professions and backgrounds.[1] Storytelling by community elders became an important aspect of the oral traditions of August First. Organizers invited speakers who remembered slavery because they were once enslaved or because they could share the experiences of older relatives who were once enslaved. In 1952 the Windsor Daily Star announced, “An unusual treat will be the appearance of Rev. William Harrison of Windsor, who will speak Sunday afternoon. He is 87 and the oldest living resident who can recall the days of slavery.”[2] Reverend Harrison, the minister of the BME church in Windsor, was an annual griot — the term for a respected traditional West-African storyteller — at Jackson Park since 1935. He talked about the early freedom seekers who journeyed to Canada. Perhaps the newspaper called his appearance unusual because it was rare at that time for the public receive such rich first-hand information. He had been born in London, Ontario, on February 24, 1866. His mother was Isabelle Nelson Harrison, a free Black woman from Kentucky, and his father was Thomas Harrison, a fugitive slave from Missouri. His brother, Richard B. Harrison, also born in London, became a famous actor in the United States. He performed in the Broadway play called The Green Pastures, which ran from 1930 to 1935.

Abolitionists, many of whom were church ministers, spoke about the moral evil of the enslavement of Africans and the urgent need to abolish the inhumane practice. Reverend William King, founder of the Elgin Settlement in Buxton, delivered a sermon at an Emancipation Day church service in Chatham in 1856, which he mentioned in his diary. In 1858 he spoke at Tecumseh Park on the state of slavery in the southern United States: “I hope the day is not far distant before this fould blot shall be wiped off from the national escutchion. The institution is doomed to destruction. Slavery cannot always last, it is in direct violation of the laws of God and the natural rights of man — a spirit of uneasiness is manifesting itself.”[3] Reverend King referred to the increased agitation to end slavery in the South that would lead to the Civil War. Picnicking and dancing followed in the barracks. Other White ministers who participated in Emancipation Day included ministers from Montreal: Henry Wilkes, John McKillican, John McVicar, and Alex Kemp, who delivered sermons in the 1860s, as well as the men listed in the White Celebrants section in Chapter 4.

Reverend William King, founder of the Elgin Settlement and Buxton Mission, the most successful planned community for fugitive slaves. By the 1860s, over 400 Black families (about 2,000 people) owned land in Buxton and helped to build a thriving community.

Courtesy of the Buxton National Historic Site & Museum.

Lecturers often expressed patriotic sentiments toward Britain for ending slavery and gratitude to Canada for being a place of refuge to fugitives. In Montreal Alexander Grant, an African-American self-employed launderer who had come from New York four years earlier, asked his audience in Montreal on August 1, 1834 (the date the Slavery Abolition Act took effect), to “join [him] heart and hand in giving [their] warmest acknowledgements to Great Britain for the noble act she has performed.” He went on to point out the privileges freed bondsmen and bondswomen could now embrace “under the protection of the British flag.”[4] In 1847 in Windsor, Black abolitionist and newspaper publisher Henry Bibb, in addressing a group of recent fugitives, said, “… now you are in Canada, free from American slavery; yes the very moment you stept upon these shores you were changed from articles of property to human beings.”[5]

Racial discrimination was another recurring topic that Emancipation Day orators tackled. In 1871 Robert L. Holden commented on the increase in racial prejudice against Blacks in Canada, particularly in Ontario and British Columbia. Robert argued that African Americans, who were only recently freed from slavery, were progressing better socially and politically than African Canadians who obtained liberty first. Robert L. Holden was also one of several speakers in Chatham in 1891 who focused their attention on denouncing the unacceptable level of racism Blacks in Ontario were facing in sending their children to public schools, employment, housing, serving on jury, and receiving service in hotels and restaurants.

Spotlight on ...

William King, a White Presbyterian minister and teacher, was living in Louisiana when he accepted a missionary position in Toronto in 1846. The following year, to his dismay, he inherited fourteen slaves from his wife’s estate. William brought them back to Canada, including a young man whom he purchased, with the intention of freeing them all. He started the Elgin Settlement in Buxton, Ontario, to help former slaves to support themselves. Today the area is known as North Buxton and is recognized as a national historic site. The Buxton National Historic Site and Museum consists of one of the schools and a log cabin of the settlement, along with some of Reverend King’s belongings. Descendants of original

settlers continue to live in the community.

Guest speakers who were “race men,” community activists concerned with the upliftment and betterment of the Black race, were always on the program. Prominent among them were Henry Bibb, in 1847 in Windsor; Frederick Douglass, in 1854 at the Dawn Settlement in Dresden; Martin R. Delany, in 1857 in Chatham; Josephus O’Banyoun, in 1878 in Hamilton, 1889 in Amherstburg, in Dresden in 1890, and in Chatham in 1891; Robert L. Holden, in 1871 and 1891 in Chatham, as well as 1895 in London; John Henry Alexander, in Amherstburg in 1894; and Stanley Grizzle, in Toronto in the 1950s. They encouraged social advancement of the African race through education, personal demonstration of integrity, and inspiring excellence.

Youth were often targeted by headline speakers, who encouraged them to pursue an education. Obtaining an education would ensure a better future for the individual, their family, and their community. In Amherstburg in 1889, Reverend E. North of Colchester South pointed out “the power of education to remove prejudices against their race, as it elevated them in all relations of life and qualified them to fill any position in the land.” In Chatham in 1891, Josephus O’Banyoun suggested that Emancipation Day should be a time to celebrate what African Canadians should be and aspired to be. Orra L.C. Hughes, a Black lawyer from Pennsylvania, addressed the gatherers in Hamilton in 1878. He stated that any man who had an impact on the world acquired knowledge by some means and that knowledge would be an important tool for Blacks in dispelling myths of African inferiority while reclaiming their position as disciplined learners.

Black speakers consistently worked to instil racial pride and a sense of history among youth and adults by educating them about the development of African civilizations and Black contributions to Canada and the world. Black nationalists, people who believed in the necessity for unity among Africans around the world, used Emancipation Day speeches to encourage African nationalism. Marcus Garvey, founder and president of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, delivered a speech with a call to action in St. Catharines in 1938. While in Toronto for the Eighth International Convention of the Negro Peoples of the World, Garvey attended the annual picnic sponsored by the Toronto division of the UNIA at Lakeside Park, Port Dalhousie, in St. Catharines. Hundreds of people heard Garvey say, “The negro must take his place in the world before it is too late,”[6] referring to the necessity of people of African origin to have their own nation, to repatriate to Africa in order to ensure the survival of the race. Pan-Africanists pressed emigration out of North America to places in Africa or the Caribbean with Black majorities to attain equality.

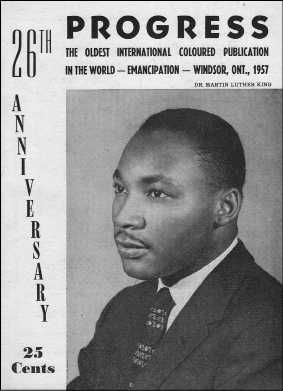

African-American civil rights activists made up a large number of the speakers in the 1950s and 1960s, especially at events in Windsor. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke there in August 1956, just after helping to kick start the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which was triggered by the arrest of Rosa Parks. Based on the Jim Crow Laws in Alabama, Rosa was required to give up her seat on the bus if it was needed by a White person. However, Rosa refused and was arrested by the police. In a show of solidarity and in an effort to change the racist law, Blacks refused to take public transit if they were going to be limited to sitting at the back of the bus. After thirteen months, the boycott ended in December 1956 when the United States Supreme Court ruled that segregation on buses was illegal.

An audience of over 5,000 at Jackson Park heard Baptist minister Martin Luther King Jr. describe the birth of a new age of justice and freedom for all men, filled with hope and possibility. He asserted that “there can be no birth without growing and pains and labor pains.” Dr. King was referring to the fervent fight against segregation that was occurring in the southern states and the slow changes towards equality and integration that were taking place. He then encouraged Blacks to “prepare for the new age of freedom” and to “achieve excellency in the areas that [they lived] in.”[7]

Civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., 1956. Dr. King travelled across America to advocate for equal rights for Blacks and the poor. In 1964 he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in acknowledgment of his non-violent movement in the fight for justice.

Courtesy of the E. Andrea Shreve Moore Collection, Essex County Black Historical Research Society.

Adam Clayton Powell Jr., a church minister and congressman from New York, delivered addresses in 1945 and 1954. At his first Emancipation Day appearance, Mr. Powell warned the 30,000 listeners,

The war is not finished and we shall not celebrate V-E Day when Japan is finished. There is another V-E Day to be anticipated. The true V-E Day will come in the United States and Canada when we celebrate equality of the races. We march towards a second emancipation ... We must not cringe before those people who in the war were ready to allow us to shed our blood in the fight but who in peace wish to give us again the mops, pail, and the broom ... There is no one here who can stop the rendezvous of the Black man with his true freedom.[8]

V-E Day was Victory in Europe Day, on May 8, 1945, when the Second World War ended. He referred to the fact that Black men have fought for equality in several wars, but have yet to obtain it for themselves in their own countries. Other American civil rights speakers included Daisy Bates, an American civil rights activist; Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, Baptist minister and civil rights activist in Birmingham, Alabama; and Mrs. Medgar “Myrlie” Evers, wife of slain civil rights activist Medgar Evers of Mississippi.

African-Canadian civil rights activists were also very involved as August First speakers. Daniel G. Hill, the first director of the Ontario Human Rights Commission, delivered an address at Victoria Memorial Park in Toronto in 1958 and discussed the historic role of African-Canadian associations in that city going back to the 1840s. George McCurdy, who was at that time the human rights administrator in Ottawa, spoke briefly at Harrison Park, Owen Sound, in 1970. George was one of the community leaders who led the fight to close the segregated schools in Ontario. The last segregated school was closed in Colchester, just south of Windsor, in 1965.

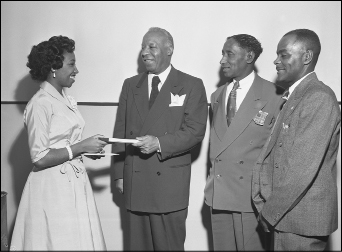

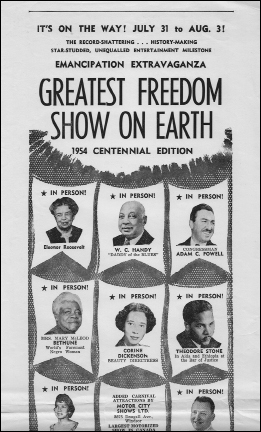

Up until the 1950s, the headline guest speakers invited to speak were all men. As a reflection of the change of the social status of women, they began to be featured speakers at Emancipation Day observances. Female speakers included former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt and Mary MCleod Bethune, both of whom addressed the crowds at Jackson Park in Windsor in 1954. Mary, an African-American civil rights activist, threw a challenge to the listeners; “We must do away with everything like segregation and discrimination where we have one man up and another down. We must build a world where every man is up and no man is down.”[9] Wife of the former U.S. president Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Eleanor delivered the speech to close the four-day festival. She talked about the freedom movements around the world in countries such as India and China and the push for equal rights by women worldwide: “There is a need for unity in the human race. People must learn to play together, work together, and live together.”[10] African-Canadian Violet King, a native of Alberta, was invited to be the featured speaker in Toronto in 1958. Four years earlier, Violet had earned the distinction of becoming the first Canadian-born Black female lawyer. On the 125th anniversary of the Slavery Abolition Act, Violet highlighted three recent accomplishments in Black Canadians’ fight for equality: serving in integrated military units in the Second World War, the unionization of the Sleeping Car Porters, and the passage of anti-discriminatory legislation such as the Fair Employment Practices Act of 1951 and the Fair Accommodation Practices Act of 1954. She summarized that all of these victories helped to narrow the gap of racism.

Violet King, left, in Calgary, Alberta with Bennie Smith and Roy Williams (second and third right), leaders of the Calgary branch of the International Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. Asa Philip Randolph, president of the North American all-Black union presents Violet with a purse in recognition of her achievement as the first African-Canadian female lawyer.

Courtesy of Glenbow Archives and Museum, NA-5600-7757a.

African-Canadian politicians like Isaac Holden, Robert L. Dunn, Ovid Jackson, and Lincoln Alexander also addressed August First assemblies.[11] Chatham alderman Isaac Holden spoke in 1871 and 1882 in Chatham. In 1882 he discussed the

philanthropy of Wilberforce and his contemporaries who sounded the first tocsin (warning signal) of freedom, for eight hundred thousand slaves. He also dealt with considerable spirit on the great emancipation in America which broke asunder the manacles of four million beings. He closed the address by urging his people to make the best of themselves and lose no opportunity to cultivate all the humanities, that their race might prove they were worthy the freedom given them.[12]

Windsor city councillor Robert L. Dunn delivered a speech in Windsor in 1895 and in Chatham in 1899.

Owen Sound’s first Black mayor, Ovid Jackson, spoke in Amherstburg in 1983 at the North American Black Historical Museum’s inaugural Emancipation Day commemoration. The Honourable Lincoln Alexander was the keynote speaker at Uncle Tom’s Cabin Historic Site in Dresden in 2005 and 2006. He spoke about the racism he had experienced as a youth and as an adult growing up in Hamilton. Alexander was born in Hamilton and achieved recognition as a lawyer and politician. He was the first Black lieutenant-governor in Ontario, Canada’s first Black member of Parliament, and the first Black cabinet minister. The former politician discussed how he overcame prejudice and how Canadians of various races have fought for equality in Ontario and across Canada. He encouraged people “to stand up and be counted and never let this sort of thing [slavery] happen again.”[13]

Spotlight on ...

Black politicians like Alderman Robert Leonard Dunn delivered speeches at Emancipation Day celebrations, as he did in Windsor in 1895. A very successful businessman, he and his brother James owned the Dunn Paint and Varnish Company. He also was a co-owner of a theatre in Detroit. Robert was one of the founding members of the Colored Citizens Association (later known as the Central Citizens Association) in the 1930s. Robert L. Dunn served as a school board trustee in Windsor, was elected alderman in 1893, and was re-elected several times until 1903.

At times, other faith leaders were asked to speak to Emancipation Day crowds. This illustrated the wide array of Canadians who fought for equality for all citizens. Rabbi Abraham Feinburg of Holy Blossom Temple in Toronto shared his insight on discrimination with those who gathered in 1964. He asserted that mankind would “destroy itself in racial conflict” if society and the world did not become colour blind. He urged listeners to see beyond the colour of someone’s skin by being accepting of everyone.

Emancipation Day speakers were articulate and eloquent. Many delivered carefully prepared addresses, while others spoke unscripted but passionately, from the heart. The purpose of including speakers in festival programs was to educate, captivate, inspire, motivate, and mobilize the Black community. Additionally, orators helped to encourage youth to make a positive impact on the future and to fight for the end of slavery and various forms of racial discrimination. Speeches were literary entertainment, an extension of African spoken word, and a means of voicing the goals and concerns of Black Canadians. The speeches were often printed later as pamphlets for educational purposes.

A poster of the featured speakers and performers at Windsor’s 1954 celebration.

Courtesy of the E. Andrea Shreve Moore Collection, Essex County Black Historical Research Society.

Toasts and Resolutions

The toasts and resolutions at Emancipation Day gatherings were also meaningful elements of the African oral culture. A toast is a tribute or proposal of best wishes, good health, and success, offered to someone or a group, and can be marked by people raising glasses and drinking together. Well-wishers could also respond in agreement, like responding with “amen” to a delivered toast. This kind of interaction between the speaker and the listener is known as “call and response,” which is another example of African oral tradition. The speaker and his or her message is affirmed by the giving of a favourable verbal response. A resolution is a formal expression of opinion by a group of people in a meeting. Both forms of speaking were used to show patriotism toward Britain and the Queen.

They also reflected how African Canadians embraced their new citizenship and the rights and privileges that came along with it. As well, toasts expressed messages to fellow White citizens that they, the Black citizens, were appreciative of the opportunities afforded to them, such as free soil, security from slavery, as well as education. They communicated that Blacks in Canadian provinces were good, productive citizens.

Proclamations and resolutions called upon the future and declared new beginnings. Resolutions would be passed to chart the course for political or social action for the year to come, expressing the issues important to Black cultural organizations and the community.

For example, these seven toasts were offered at the gathering in Toronto in 1854:

- The Queen — three cheers

- The army and navy of Great Britain — three cheers

- The Governor General — three cheers

- “The Provincial Freeman” — remarks by the president and three cheers

- Three cheers for the Toronto and Hamilton Bands

- Resolved, That we celebrate the 1st of August, 1855 at Hamilton

- Concluding toast — “Our Wives and Sweethearts.”[14]

The toasts proposed in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1855 showed the racial and global awareness of the long-established Black community. They acknowledged their African roots. Black Haligonians were loyal to their country and to the British crown. Further, the toast reflected their understanding of the necessity of an international coalition in attacking slavery:

- Africa — the land of our fathers …

- The Queen — God bless her. Long may she reign over a free and generous nation.

- Prince Albert, Prince of Wales, and all the Royal Family.

- General Simpson, and the Allied armies in the Crimea …

- Sir Gaspard Le Marchant, Governor, and Commander-in-Chief, and the British Army.

- Vice Admiral Fanshawe, and the British Navy.

- Wilberforce and Clarkson — the noble advocates for African liberty.

- The President and Abolition Society of Nova Scotia.

- The health of the Abolition Society in Canada, Bermuda, and all the West India Islands, who assemble in honor of this day.

- The Lord Bishop and the Clergy of Nova Scotia.’11th. The Mayor and Corporation.

- The Press of Nova Scotia.

- Lady Le merchant, and the fair daughters of Acadia.

- Our next merry meeting.[15]

The collective declaration passed at Emancipation Day in 1896 in London, as noted by a newspaper, was as follows:

God bless the Baptists, continued the speaker.

“Amen.”

GOD BLESS THE POLITICAL PARTIES.

“God bless the Conservatives.”

“Amen.”

“God bless the Reformers.”

“Amen.”

“Amen make Laurier a man that will protect this country and not give away its rights to the United States.…”

“God bless England,” shouted somebody in the crowd.

“God bless England for her protection, for every good act she has done. God bless the Queen who sits on the throne and rules so nobly for men of all nationalities and colors….”

“Three cheers for the Queen,” concluded Mr. Bazie, and they were given.[16]

Toasts and resolutions kept to a similar format wherever they were delivered, and they were regularly printed in local newspapers. They were usually drafted by members of the organizing committee. This media publicity meant that White Canadians got to see that Blacks shared some of the same feelings, sentiments, and aspirations.

Readings

Readings were a significant ritual of the usual August First program. For example, sections of the Slavery Abolition Act, the Emancipation Proclamation, and the Thirteenth Amendment would have been read to those in attendance. Laws that had a significant impact of the lives of people of African origin in North America were shared. The British Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 that was passed on August 28, 1833, for example, read, “Whereas divers persons are holden in Slavery within divers of His Majesty’s Colonies, and it is just and expedient that all such Persons should be manumitted and set free ...”

The Emancipation Proclamation was officially issued on January 1, 1863. While it did not end slavery, it provided the anticipated outcome of the Civil War if the Union Army won:

... all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people thereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free ... I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.

The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, enacted on January 31, 1865, abolished slavery in America. It took effect on December 18, 1865. Section one read, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” This is some of what was imparted to listeners.

As time went on, other freedom laws that were passed in Canada and the United States were read, such as the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution, the Fair Employment Practices Act of 1951, the Fair Accommodations Practices Act of 1954, the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.[17] Copies were often put on display as well. Readings of freedom documents were another way in which patriotism and thanksgiving were exhibited. After the Reconstruction Era (1865 to 1877), the years after the Civil War and the end of American slavery, Emancipation Day readings commemorated North American Blacks’ entitlement to constitutional rights.

The literary works of Black authors, including books, essays, and poems, were often recited. Written pieces that emphasized collective feelings and emotions or personified relevant social concerns were selected. Sharing their work illustrated the success of Black writers.

The oral tradition feature of Emancipation Day was a vital part of the education of celebrants. The purpose was to pass on the history from one generation to the next to guarantee that the diverse history of Black peoples was kept alive. It armed African-Canadians with the ammunition needed to continue the fight for freedom and equality.