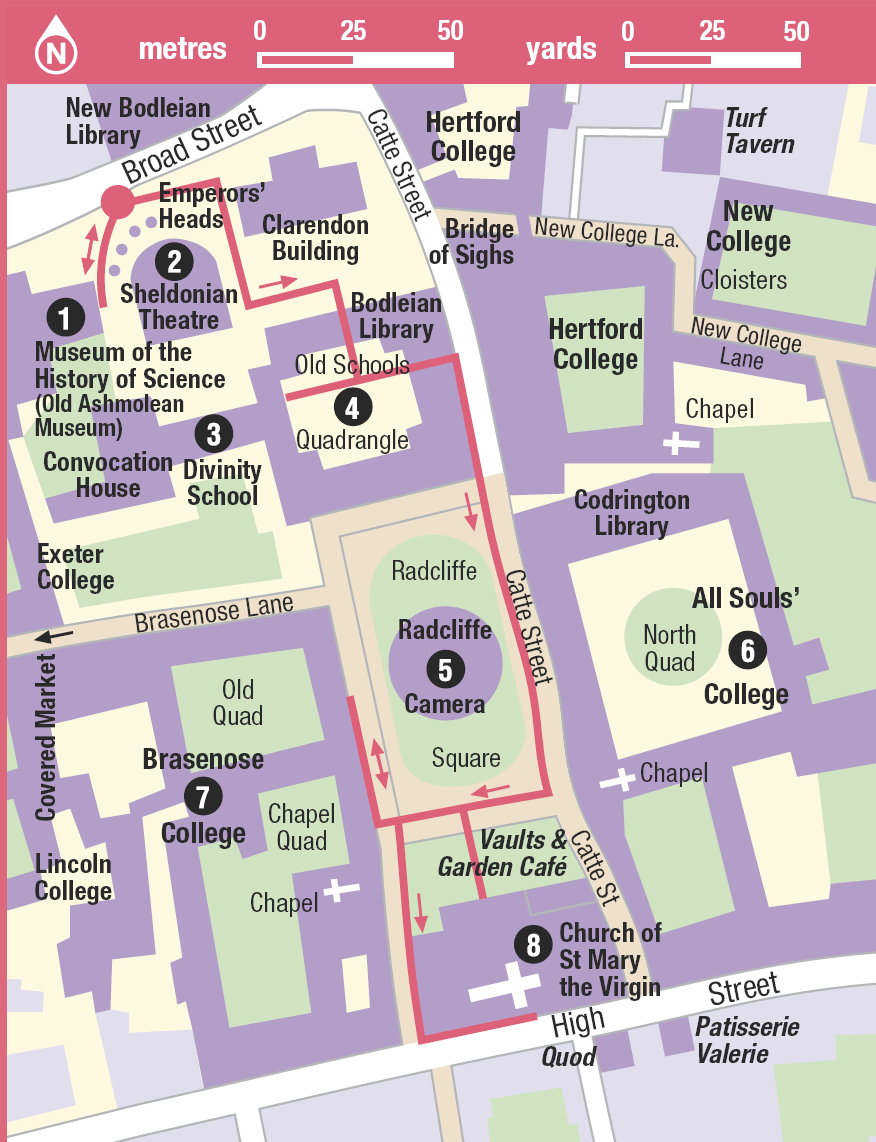

Tour 1 : The Heart of the University

Follow in the footsteps of Harry Potter, Inspector Morse, Christopher Wren and Thomas Cranmer for an hour or two on this ¼ mile (0.4km) stroll around the university

Highlights

While the busy crossroads of Carfax is usually considered the centre of the City of Oxford, the university – founded as it is on the college system – has no such focal point. Yet there is one area that, by virtue of the historic role of its buildings, can be described as the heart of the university. Lying between the High Street and Broad Street, it also represents one of the finest architectural ensembles in Europe.

Bodleian Library.

Dreamstime

Bearded Ones

At the eastern end of Broad Street, visitors are met by the intimidating gaze of the Emperors’ Heads, or ‘Bearded Ones’, which tower over the railings separating the street from the precinct of the Sheldonian Theatre. Such busts were used in antiquity to mark boundaries, but no one knows whom these particular ones represent. They were installed in 1669, the same year that the theatre was completed, but over the years their features eroded so considerably that they were no longer recognisable even as faces. Facelifts were performed by a local sculptor in 1970.

One of the curious Emperors’ Heads.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Science Museum

To the right is the Old Ashmolean Museum, the original home of the famous art and antiquities museum before it moved to Beaumont Street. Designed by Thomas Wood and completed in 1683, it is considered one of the most architecturally distinguished 17th-century buildings in Oxford.

It now contains the Museum of the History of Science 1 [map] (tel: 01865 277 280; www.mhs.ox.ac.uk; Tue–Fri noon–5pm, Sat 10am–5pm, Sun 2–5pm; free), with the world’s finest collection of European and Islamic astrolabes, as well as quadrants, sundials, mathematical instruments, microscopes, clocks and, in the basement, physical and chemical apparatus, including that used by Oxford scientists in World War II to prepare penicillin for large-scale production. Also on display in the basement is a blackboard used by Albert Einstein in the second of his three Rhodes Memorial Lectures on the Theory of Relativity, which he delivered at Rhodes House, Oxford, on 16 May 1931. Part of the basement was once used as a dissecting room, and set into the stone floor you can see a number of small holes. The legs of the dissection table were slotted into these holes to keep the table still while professors and students worked on the corpses. The museum also runs a programme of talks, guided tours and workshops. See the website for details of family events where you can look through old telescopes or take part in scientific experiments.

Original University Press

The imposing neoclassical edifice to the left of the heads is Nicholas Hawksmoor’s Clarendon Building, erected in 1715 – erstwhile home of Oxford University Press. The OUP’s first home was the basement of the Sheldonian Theatre, but this was far from ideal as compositors had to move out every time the theatre was required for a ceremony. However, between 1702 and 1704 the Press published its first bestseller, Lord Clarendon’s History of the Great Rebellion, and subsequent profits enabled the University to erect this new building. The Press moved out of the Clarendon to its present site on Walton Street in 1830, but it is still used for meetings of the Delegates of the Press, the University committee that directs its affairs. Around the roofline are James Thornhill’s sculptures of the nine Muses.

Sheldonian Theatre

Through the gateway is the Sheldonian Theatre 2 [map] (tel: 01865 277 299; www.sheldon.ox.ac.uk; Mon–Sat 10am–12.30pm, Mar–Oct 2–4.30pm, Nov–Feb 2–3.30pm, though times can vary depending on functions; charge). Commissioned by Gilbert Sheldon, Chancellor of the University, in 1662, this was Christopher Wren’s first architectural scheme, which he designed at the age of 30, while still a professor of astronomy. Modelled on the ancient open-air Theatre of Marcellus in Rome, but roofed over to take account of the English weather, the Sheldonian was built primarily as an assembly hall for more or less elaborate university ceremonies. Chief among these is the Encaenia – the bestowing of honorary degrees that takes place each June.

For most of the year, however, the Sheldonian is used for concerts. It is not the most comfortable of venues, with its hard seats, but is a fine interior nonetheless, spanned by a 70ft (21m) diameter flat ceiling, painted with a depiction of the Triumph of Religion, Arts and Science over Envy, Hate and Malice. The ceiling, with no intermediate supports, is held up by huge wooden trusses in the roof, details of which can be seen on the climb up to the cupola, which, though glassed in, provides fine views over central Oxford.

Music to the Ears

Ever since 1733, when Handel was honoured with a Doctor’s degree in music, which was celebrated with a week of performances of his music here, the Sheldonian has been the venue for a large variety of classical concerts. For further information, contact Music at Oxford (www.musicatoxford.com) or the Oxford Philomusica Orchestra (www.oxfordphil.com), which often performs here as well as at other venues in the city.

The Sheldonian Theatre offers fine views from the rooftop cupola.

Sheldonian Theatre

To the south of the Sheldonian, through the small gateway into Old Schools Quadrangle, are the buildings of the Bodleian Library (tel: 01865 277162; www.bodley.ox.ac.uk). Before admiring the beautiful main courtyard in too much detail, first journey back in time by entering the doors behind the bronze statue of the Earl of Pembroke (a university chancellor) and proceeding through the vestibule into the much older Divinity School 3 [map] (tel: 01865 277 224; Divinity School only: Mon–Fri 9am–5pm, Sat 9am–4.30pm, Sun 11am–5pm; charge, except for children under 15). It is well worth taking a guided tour, since it will allow you to see areas not otherwise accessible, including Duke Humfrey’s Library (tours Mon–Sat 10.30am, 11.30am, 1pm and 2pm, Sun 11.30pm, 2pm and 3pm, university ceremonies permitting; charge). The Bodleian runs a Family Tour and a History Trail for children.

Harry Potter

The makers of the Harry Potter films made extensive use of Oxford as settings for numerous scenes. Most notably, the Divinity School became Hogwarts Sanatorium and Duke Humfrey’s Library doubled up as Hogwarts Library. Other films set in various parts of the Bodleian complex include Philip Pullman’s The Golden Compass, Shadowlands (about C.S. Lewis, author of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe) and The Madness of King George (in which the Divinity School stands in for Parliament’s House of Commons).

Regarded by many as the finest interior in Oxford, work began on the Divinity School itself in 1426, following an appeal for funds by the university. Being the most important of all subjects at the time, theology required a suitable space, but money kept running out and the room took almost 60 years to complete. Its crowning glory is the lierne-vaulted ceiling, which was added in 1478, after the university received a gift from Thomas Kemp, Bishop of London. Completed by local mason William Orchard, the ceiling is adorned with sculpted figures and 455 carved bosses, many bearing the arms of benefactors.

Divinity School vault.

iStockphoto

Candidates for degrees of Bachelor and Doctor of Divinity were not the only people to demonstrate their dialectical skill under this glorious ceiling. It was here, too, that Latimer, Ridley and Cranmer were cross-examined by the Papal Commissioner in 1554, then condemned as Protestant heretics.

Duke Humfrey’s Library

In around 1440, a substantial collection of manuscripts was donated to the university by Humfrey, Duke of Gloucester, the younger brother of Henry V. The walls of the Divinity School were built up to create a second storey for Duke Humfrey’s Library. The library, with its magnificent beamed ceiling, was first opened to readers in 1488, but was defunct by 1550, largely as a result of neglect and the emergence of book printing (which rendered manuscripts redundant), but also owing to the depredations of the King’s Commissioners after the dissolution. It was while he was a student at Magdalen College that Thomas Bodley became aware of this appalling state of affairs. Posted abroad as Ambassador to the Netherlands by Queen Elizabeth I, he used his far-reaching network of contacts to establish a new collection of some 2,000 books to restart the library. The room was restored and opened once more in 1602, and subsequently extended by the addition of the Arts End. Here, visitors can see original leather-bound books dating from the 17th century, some of them turned spine inwards so that chaining them to the shelves (a common practice) would cause less damage.

Postcard-perfect – the Radcliffe Camera, the earliest example in England of a circular library, and All Souls’ College to the right.

Dreamstime

Old Schools Quadrangle

In 1610, an agreement was made whereby the library would receive a copy of every single book registered at Stationers’ Hall. Soon, Bodley’s collection had grown so large that a major extension was required, hence the Old Schools Quadrangle 4 [map] . Though only the cornerstone was laid before Bodley’s death in 1613, this magnificent piece of architecture, designed in Jacobean-Gothic style, can be regarded as the culmination of his life’s work. The quadrangle boasts a wonderful serenity, and despite being built much higher than college quads is still light and airy.

The view from Broad Street through the historic corridors of the Bodleian Library.

iStockphoto

Underground Storage

The Radcliffe Camera is by no means the latest addition to the library. In 1930, the huge New Bodleian Library was opened on the other side of Broad Street to house the overspill. The new library is linked to the old one by a system of underground conveyors, and books lie just below the surface of Radcliffe Square. The Bodleian not only has to cope with a constant flow of new book titles, but also every single newspaper and magazine published in the UK – literally millions of items, including some priceless treasures. The New Bodleian is currently being revamped to make it more accessible to the public (completion 2015).

The quadrangle was also built as the new home of the various schools of the university. Their Latin names can be seen in gold lettering painted on a blue background above the doors. Above these is the library space, but the continuity around the quad is broken at the east end by the splendid gate-tower, or ‘Tower of the Five Orders’ – so named because it is ornamented with columns and capitals designed to provide students with an introduction to the five orders of classical architecture: Doric, Tuscan, Ionic, Corinthian and Composite. In a niche on the fourth storey is a statue of James I, the reigning monarch when the quadrangle was built.

Radcliffe Camera

Leaving the quad through the eastern exit and turning right, you come to the broad expanse of Radcliffe Square, dominated by the most familiar symbol of Oxford, the Radcliffe Camera 5 [map] (closed to the public). Dr John Radcliffe, a famous Oxford physician, bequeathed the sum of £40,000 to found a library on his death in 1714.

Based on an idea by Nicholas Hawk-smoor, this purely classical, circular building, surmounted by a dome, was ultimately designed by James Gibbs and completed in 1749. Absorbed as a reading room of the Bodleian in 1860, the building was part of a grand 18th-century scheme to open up this area of the city as a public square, and replace the existing jumble of medieval houses. Not all the plan was realised, but it is impressive how the circular Radcliffe Camera appears to fit so naturally into the rectangular square.

All Souls’

To the east of the Radcliffe Camera is the gateway to the North Quadrangle of All Souls’ College 6 [map] (visitor entrance on the High Street; tel: 01865 279 379; www.all-souls.ox.ac.uk; Mon–Fri 2–4pm; free). Founded in 1438, this is the only college in Oxford never to admit any students, restricting membership to Fellows only, providing them with facilities to pursue their research (as well as fine vintages from Oxford’s largest wine cellar).

The distinctive twin towers of All Souls’ College.

Fotolia

Much of the North Quad is the result of 18th-century alterations and additions, which came about after the medieval cloisters were levelled and a Fellow, Christopher Codrington – whose fortune was founded on the slave trade – bequeathed much of his estate, including a large collection of books, to the college. The resulting Codrington Library (viewing only by special permission) occupies the building on the north side of the quad. Designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor, the exterior (with the enormous sundial by Wren) is in Gothic style to mirror the chapel opposite, while the interior is purely Renaissance.

The eastern edge of the quad is dominated by distinctive twin towers, also by Hawksmoor, while the southern side accommodates the 15th-century chapel, complete with original hammerbeam roof and a magnificent reredos behind the main altar.

Brasenose College

On the other side of Radcliffe Square is the main entrance to Brasenose College 7 [map] (tel: 01865 277 830; www.bnc.ox.ac.uk; generally open in the afternoons – telephone for exact times; charge). The battlemented gate-tower and the Old Quad behind it date from 1516, but the latter was altered a century later by the addition of attic rooms with dormer windows. The most distinctive feature of the quad is the sundial on the north wall. Looking back after crossing to the far side, visitors are treated to one of the most startling views in Oxford, with the huge dome of the Radcliffe Camera looming above the entrance tower, and the spire of St Mary’s church to the right.

Statue adorning the facade of the Church of St Mary the Virgin.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Brasnose College is named after the ‘brazen nose’ – a bronze door-knocker – that once hung on its gates. In medieval times, anyone fleeing the law could claim sanctuary within by grasping the knocker. However, in the 1330s some students stole the ring and took it to Stamford where they intended to establish a rival university. Edward II refused to sanction the breakaway institution, but the brazen nose remained on a house in Stamford until 1890, when the college bought the whole building in order to retrieve the knocker. It is now hung in the dining hall. Meanwhile, in 1509, a replacement knocker had been commissioned. Shaped like a human head, this can be seen at the apex of the college’s main gate.

Landmarks from the Tower

The views from the top of the University Church are superb. Due north is the Radcliffe Camera with the Bodleian Library behind. To the east, the High Street curves away towards the River Cherwell, with the bell-tower of Magdalen College in the distance. Due south, the squat tower in front of Christ Church Meadow is Merton College Chapel, while to the southwest looms the cupola of Christ Church’s Tom Tower. At the top of the High Street to the west is Carfax with its tower, and beyond it the round, green spire of Nuffield College. Just below, is Brasenose College and, beyond, the neo-Gothic chapel of Exeter College.

Immediately to the north of Brasenose, the narrow Brasenose Lane leads through to Turl Street and the Covered Market. The cobbled gully down the middle marks the line of the original open sewer.

Church of St Mary the Virgin

The Church of St Mary the Virgin 8 [map] (tel: 01865 279 113; www.university-church.ox.ac.uk; daily 9am–5pm, July–Aug to 6pm; charge for tower), with its soaring 13th-century spire, completes the harmony of Radcliffe Square. It can be regarded as the original hub of the university, for it was here in the 13th century that the first university meetings and ceremonies were held, and all the administrative documents kept.

Before entering via its north door you will see, on the left, the entrance to the Vaults and Garden Café. There can be few cafés with a history such as this, for it occupies the space of the former Convocation House, an annexe built in 1320 specifically to house the University governing body, which continued to meet here until 1534 when the administration moved to Convocation House at the west end of the Divinity School. The vault is beautiful, but in summer the garden is the perfect place to rest a while.

The Interior

Now entering the vestibule from the north side, visitors are first given the option to climb the tower (Mon–Sat 9am–5pm, Sun 11.45am–5pm; charge). After a series of steps and walkways, the ascent culminates in a narrow spiral staircase, which finishes at the gangway at the base of the spire.

Back down on the ground again, the 15th-century nave is a fine example of the Perpendicular Gothic style, with slender, widely spaced columns and large windows. Look out for the pillar opposite the pulpit in the north side of the nave which has been cut away; this was done to build a platform for the trial of Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, in 1556, a major event in English history.

Cranmer faced his persecutors for the last time here. Having witnessed the deaths of fellow martyrs Bishops Latimer and Ridley six months earlier, he was already a condemned man. But the Papal Commissioner now expected him to denounce the Reformation. Cranmer refused to do so, instead retracting all the written recantations he had previously penned; he was dragged from the church and taken back to his cell in the Bocardo prison above the city’s North Gate before being burned at the stake in Broad Street.

Church detail.

Corrie Wingate/Apa

Oxford Movement

Almost 300 years later, the church was again the centre of controversy when, in 1833, John Keble preached his famous sermon on national apostasy. This led to the founding of the Oxford Movement, which espoused a renewal of Roman Catholic thought within the Anglican Church and whose ideas were published in 90 Tracts for the Times (1833–41). A leading Tractarian was John Newman, vicar of St Mary’s, who ultimately converted to Catholicism and became a cardinal. Oxford remains a major centre of High-Church Anglo-Catholicism to this day.

Leave the church and venture round onto the High Street to study the main entrance of St Mary’s, the South Porch. Built in 1637, with its twisted columns, broken pediment and extravagant ornamentation, the porch bears all the hallmarks of the Italian Baroque, and was directly inspired by the canopy which had just been built by Bernini over the high altar of St Peter’s in Rome.

Eating Out

Patisserie Valerie

90 High Street; tel: 01865 725 415; www.patisserie-valerie.co.uk; Mon–Sat 8am–7pm, Sun 9am–7pm. Smart café serving breakfast all day and salads and other lighter meals from lunchtime onwards. It is the cakes and pastries, however, that are this outfit’s speciality. £–££

Quod Restaurant and Bar

92–4 High Street; tel: 01865 202 505; www.quod.co.uk; daily 7am–11pm. A stylish and bustling brasserie-style establishment, offering a varied menu with an Italian slant. It is particularly worth visiting during the week between the hours of noon and 7pm, when an excellent-value set-lunch menu (£) is available. Children are welcome here. ££–£££

Vaults and Garden Café

Vaults of the University Church, entrance from Radcliffe Square; tel: 01865 279 112; www.thevaultsandgarden.com; daily 8.30am–6.30pm.

This informal café-restaurant serves soups, salads, sandwiches, cakes and other snacks daily. £