In the period leading up to the Great War, during it and indeed following it, the main forms of entertainment in England were the music halls and variety theatres. Famous artists used their voices for the war effort. Miss Florrie Forde amused audiences with ‘It’s A Long Way to Tipperary’, and ‘Take Me Back to Dear Old Blighty’. These were common entertainments for common people, though humour was a touch coarse, and unfettered by any of the sensibilities we have come to know in the twenty-first century with regards to issues of feminism and racism. This was probably not because folk were rude or insensitive, but rather because they were preoccupied with more immediate issues of mortality and survival.

The text of the song that follows, originally from the comic singer Billy Merson (and which Taffy Thomas has heard sung on several occasions by Essex folk singer Simon Ritchie), has to be considered in the context of the 1900s, where it elicited hearty chuckles and belly laughs from both men and women, together enjoying a bit of escape from the death and destruction of Flanders Fields. If you find yourself chuckling likewise, just enjoy those few moments of freedom and guilty pleasure.

When first I made me mind up that a soldier I would be,

The girl that I was courting she came round and said to me

‘I’ve had me photo taken, Bill, and if we are to part

Promise me you’ll always wear the photo next your heart.’

She hung the locket round my neck and her ruby lips I kissed

Borrowed the fare to Aldershot and off I went to enlist.

Chorus:

With the photo of the girl I left behind me

I went and joined the army full of glee

Then someone came up to remind me

The doctor wanted to examine me.

When the doctor found the locket next my heart he said to me

‘Whose photograph is this sir that I find?

Is this the captain’s bulldog?’ I said, ‘No, sir, if you please, sir

It’s the photo of the girl I left behind.’

I never shall forget the first day that I went under fire

I’d been looking at the photo of the girl that I admire

I thought her lovely face would encourage me to go

And fight like Englishmen should do when going to face the foe.

The Captain said, ‘We’re cornered, boys, so fight like mad you must.’

I kissed the photograph and then you couldn’t see me for dust.

Chorus:

With the photo of the girl I left behind me

I rushed into the thickest of the fray

When the Captain said, ‘We’re out of ammunition

I’m afraid it’s going to be a losing day.’

I said, ‘Don’t worry over ammunition, if you please

I have something far more terrible you will find

I will rush amongst the enemy and I’ll frighten them to death

With the photo of the girl I left behind.

With the photo of the girl I left behind me

I went to practise shooting one Summer day

When we found a gust of wind had been unkind and

Blown the blooming target right away.

The Captain said, ‘The target’s gone whatever shall we do?’

I shouted just to cheer him, ‘Never mind

If you haven’t got a target and you want something to shoot at

Here’s the photo of the girl I left behind.’

Song lyrics written and composed by

Billy Merson (1881–1947)

![]()

Billy Merson’s song is actually a cheeky version of the following, traditional folk song dating back to the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, known simply as ‘The Girl I Left Behind Me’. The sad words of this traditional song were particularly relevant to the men who went off to the Great War, who would sing it about their loved ones back home.

The hours sad I left a maid

A lingering farewell taking

Whose sighs and tears my steps delayed

I thought her heart was breaking.

In hurried words her name I blest

I breathed the vows that bind me

And to my heart in anguish pressed

The girl I left behind me.

Then to the East we bore away

To win a name in story

And there where dawns the sun of day

There dawned our sun of glory.

The place in my sight

When in the host assigned me

I shared the glory of that fight

Sweet girl I left behind me.

Though many a name our banner bore

Of former deeds of daring

But they were of the day of yore

In which we had no sharing.

But now our laurels freshly won

With the old one shall entwine me

Singing worthy of our size each son

Sweet girl I left behind me.

The hope of final victory

Within my bosom burning

Is mingling with sweet thoughts of thee

And of my fond returning.

But should I n’eer return again

Still with thy love I’ll bind me

Dishonors breath shall never stain

The name I leave behind me.

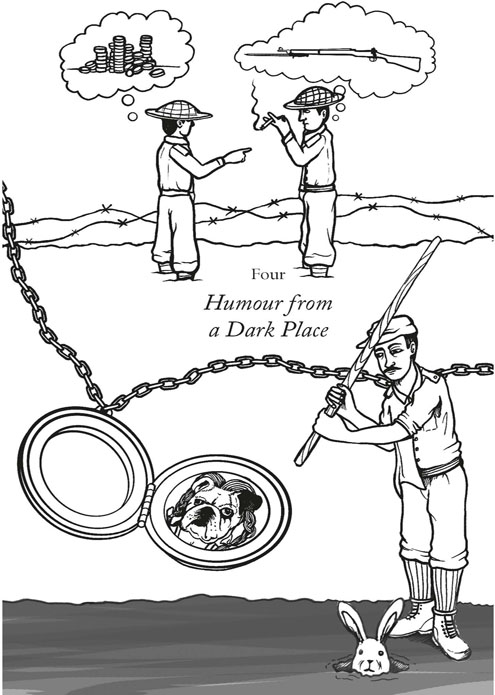

An old soldier from the Devonshire Regiment, Wrey Tucker, lived in the small Devon village of South Zeal near Okehampton until his death in 2012. A caretaker at the local primary school, Wrey told the story that follows to Taffy Thomas over several games of cribbage. It’s amazing how expensive collecting a new tale can be at a penny a point! Wrey told this as a Second World War story, although conversations indicated it was a First World War story that he had recycled.

The soldiers of the Devonshire Regiment had completed their training on Dartmoor prior to their posting to France, and they had one more training week at the barracks at Catterick Camp in North Yorkshire to endure.

After a long journey, the Devon men settled into their Nissen huts at the barracks, and went down to the mess for a meal. The food was disgusting. The Dartmoor and Exmoor boys all agreed that they had to do something about it.

They noticed that at the back of the officer’s mess stood a tatty old upright piano. The visitors stripped some of the strings from the scrapped musical instrument and fashioned some snares. Then they slipped out of camp to the moorland, returning later with about a dozen snared rabbits.

The Devon boys, poachers to a man, knew well what to do next. Using the long nail on each rabbit’s foot, they paunched and skinned the dead coneys then they delivered the fresh meat to the kitchen and a fine stew was cooked up.

Sitting down to supper that night was a much more pleasurable experience for both the West Country visitors and their Yorkshire hosts. The colonel of the ‘Yorkies’ commented on the ‘fine tucker’, and enquired as to its provenance. One of the Devon boys told him he wouldn’t normally disclose such information. However, as they were all in ‘that damned war together’, he would. He told the Yorkshire officer that, where his boys came from, people called it ‘underground mutton’.

Fascinated, the colonel asked how one could acquire such ‘underground mutton’.

Mischievously, the Dartmoor private told him that he had to get a bloody great stick and make his way out onto the moors until he spotted a hole in the bank. Then he had to stand by the hole, raise the stick, and make a noise like a carrot. When the brown hairy ears appeared … ‘BANG!’

Despite the cheek of the junior soldier, even the dour Yorkshire officer managed a smile, for now even he had a story to tell.

As in the ‘underground mutton’ story, soldiers on the battlefront during the Great War would sometimes supplement their rations with wild rabbit or – if they were lucky – produce from nearby farms. But undoubtedly, life on the front line was tough and energy-sapping and so it was essential that soldiers were kept well fed – not only to maintain their health but also their morale. Conditions in the trenches were often unsanitary and cooking and storing food in these conditions was never going to be easy. However, thanks to a French chef named Alexis Benoit Soyer (1810–58), cooks were able to provide the troops with adequate meals, cooked well.

Soyer’s contribution was an invention he designed in 1849 and which was known as Soyer’s Magic Stove. The stove was small enough to be taken anywhere and was powered by pressurised fuel which could become hot enough to cook food – and more importantly to kill any bacteria in the ingredients – in just a few minutes.

Soyer took his stove to the Crimean War, realising that soldiers there were more in danger of dying from food poisoning than from war wounds. Yet Soyer did not stop there; he also made sure that every regiment had a cook, trained personally by him.

Soyer’s Magic Stove was so successful that it travelled with many Victorian explorers on their expeditions and was even used to prepare a meal on the top of one of Egypt’s pyramids. Sixty-five years after its invention, the Soyer Stove was also an essential piece of life-saving equipment in the field kitchens of the First World War.

The heavy and light engineering communities around the edge of Birmingham, including places such as Dudley, Walsall, Wolverhampton, Quarry Bank and Cradley Heath, have been known as ‘The Black Country’ since the Industrial Revolution. The area was famous for chain and nail making; amongst other things. The anchor chain for the RMS Titanic was made there and the Cradley Heath women chainmakers’ strike of 1910, called when the employers refused to pay a proposed minimum wage, was a landmark in industrial relations history.

But in this tough area, where local culture includes such delicacies as faggots and peas and groaty pudding, a sense of humour has prevailed. The main protagonists of this Black Country wit have always been and indeed continue to be Enoch (pronounced Anock) and Eli (pronounced Ali). As many Black Country men served in the Great War, it should be no surprise that Enoch and Eli joined up together.

Black Country storyteller, Graham Langley, told the tale which follows to Taffy Thomas at Whitby Folk Festival in 2012.

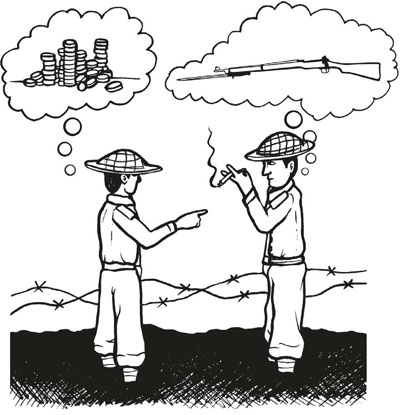

Enoch and Eli stood knee-deep in mud and blood in a trench, sharing a Woodbine – or a ‘coffin nail’ as they called it.

Enoch reminded Eli that the good news was that the major had promised them a pound for every German they shot.

Enoch then told Eli that he didn’t want to worry him, but the bad news was that there were £2,000 worth streaming across no-man’s-land with fixed bayonets.

History doesn’t recall Eli’s response, although it’s possible that the two pals’ last words came quietly in the form of the following song:

Take me back where the smoke blows black

And the home-brewed ales flows free,

And factory wenches line all the park benches,

Cradley Heath means home to me.

However, due to the miracle of reincarnation allowed by the oral tradition, Enoch and Eli tales continue to thrive in this very special part of the Midlands.

Before anyone wearing an anorak contacts us with the information that the song ‘Cradley Heath means home to me’ wasn’t composed till the 1960s, we know; but as Enoch and Eli are a concept not constricted by any logical time frame, the authors are claiming a certain amount of poetic licence.

Throughout the 1970s, Taffy Thomas’ folk theatre company, Magic Lantern, was fortunate to have as its lead singer the renowned Wolverhampton songwriter, Bill Caddick. Sometime during this period, Bill heard a story claiming that the song ‘It’s A Long Way To Tipperary’, which was composed by Black Country variety artist Jack Judge in one night just prior to the outbreak of the First World War, was sung to win a bet in a pub. Bill turned this snippet into one of his finest songs, ‘The Writing of Tipperary’. For this collection, Taffy has turned it back into a spoken word version.

The story begins with a family originating from Ireland. The communities that surround Birmingham, such as West Bromwich and Oldbury, have long provided sanctuary for immigrant Irish families fleeing the horrors of war and famine.

The family of Rodger Judge first came to the English Midlands from County Mayo in 1860. Eleven years later, in 1871, Rodger’s youngest son, John Junior, married Mary McGuire in Oldbury. In 1872, their first child, John Thomas (known as Jack), was born and the family moved into Low Town near the Malt Shovel public house. Before long, Jack had two sisters: Jane-Ann and Mary.

Although the Judge family lived in poverty, Jack grew to be a big, striking, red-haired lad, tall and strong beyond his age. To help support his family, at the age of twelve Jack bluffed his way into a job with his father at Bromford Ironworks. Jack was popular, often whistling and always with a cheery quip or a ditty to sing.

In 1885, Jack and his father left the ironworks to become fish dealers. Together they opened a wet fish stall next to ‘Polly on the Fountain’, a drinking fountain opposite the Junction Vaults.

At that time, the main places of entertainment in Oldbury were the music halls – the Gaiety and the Old White Swan Museum and Concert Hall. Jack and Jane-Ann, his sister, sometimes went to the evening events at these venues, as well as to local public houses, to sell fish, cockles, mussels, whelks and prawns. This Black Country tradition continued until the 1960s, when Taffy Thomas himself was resident in Dudley.

It was by watching the professionals at work during these visits to the halls that young Jack began to develop his own singing and comedy talent and he started to enter talent competitions. By the late 1890s, Jack Judge had become well known locally and was even offered some engagements further from home. However, Jack had to balance his entertainment ambitions against the survival of the family fish business, as his father had perished from TB at the age of thirty-eight.

As a grown man, Jack spent a lot of time in the Malt Shovel where the landlord’s brother, Harry Williams (a disabled pianist), took time to write down and arrange Jack’s songs. This was something Jack himself could not do, as he was virtually illiterate. In return, Jack promised Harry that if he ever got a song published, he would include his friend in the credits as co-author.

One night in the Malt Shovel, Jack was asked to oblige with a song. Accompanied by Harry, he launched into a tune called ‘It’s A Long Way To Connemara’.

A large Irish navvy, full of ale at the bar, seized Jack by the kerchief and muttered, ‘I’ll have you know, I’m a Tipperary man’.

Rather than get a bloody nose, Jack thought on his feet and came up with a new song. His friend Harry transcribed it as Jack was singing it, and then Jack put the words and music in a battered leather music case, which he took to all his performances.

When on tour to halls farther afield, Jack usually sought solace between shows in one of the local hostelries. He’d developed a scam. Easing the conversation around to his song-writing ability, he would bet strangers that he could compose a new song in one night and sing it at the next performance. He did this knowing that he had dozens of unused songs in that battered leather music case.

In January 1912, Jack was performing at the Grand Theatre in Stalybridge just east of Manchester. Being there for several nights, he was staying in a nearby pub and it was in that pub one evening that he pulled the song-in-a-night scam. Jack won five shillings when, on the 31 January, he sang ‘It’s A Long Way To Tipperary’ – his new song!

Once out of that leather music case, the song began to fly. Other performers, including the famous music-hall star Florrie Forde, took it up and publisher Bert Feldman signed up the royalty in September 1912, adding another ‘Long’ to the title, and including Harry Williams as co-author of ‘It’s A Long, Long Way To Tipperary’.

The sheet music was billed as ‘the marching anthem of the battlefields of Europe’ and, within two years, nearly every serviceman marching off to the Great War knew it. Even at Armistice Day in 2013, the veterans marched past the Cenotaph in London still singing this tune. Just imagine what Jack Judge would have said had he known this when he won his five bob in 1912.

![]()

Up to mighty London

Came an Irishman one day.

As the streets are paved with gold

Sure, everyone was gay,

Singing songs of Piccadilly,

Strand and Leicester Square,

Till Paddy got excited,

Then he shouted to them there:

It’s a long way to Tipperary,

It’s a long way to go.

It’s a long way to Tipperary

To the sweetest girl I know!

Goodbye, Piccadilly,

Farewell, Leicester Square!

It’s a long, long way to Tipperary,

But my heart’s right there.

Paddy wrote a letter

To his Irish Molly-O,

Saying, ‘Should you not receive it,

Write and let me know!’

‘If I make mistakes in spelling,

Molly, dear,’ said he,

‘Remember, it’s the pen that’s bad,

Don’t lay the blame on me!’

It’s a long way to Tipperary,

It’s a long way to go.

It’s a long way to Tipperary

To the sweetest girl I know!

Goodbye, Piccadilly,

Farewell, Leicester Square!

It’s a long, long way to Tipperary,

But my heart’s right there.

Molly wrote a neat reply

To Irish Paddy-O,

Saying ‘Mike Maloney

Wants to marry me, and so

Leave the Strand and Piccadilly

Or you’ll be to blame,

For love has fairly drove me silly:

Hoping you’re the same!’

It’s a long way to Tipperary,

It’s a long way to go.

It’s a long way to Tipperary

To the sweetest girl I know!

Goodbye, Piccadilly,

Farewell, Leicester Square!

It’s a long, long way to Tipperary,

But my heart’s right there.

Jack Judge and Harry Williams (1912)