The English county of Cumbria has a long history of legend and folklore. Its beautiful, often wild and rugged landscape, with Lakeland as the jewel in its crown, is not surprisingly a natural source of inspiration for storytellers and writers. This was certainly the case in Victorian times, when Lakeland became a popular destination and place of residence for poets and storytellers like the great William Wordsworth, John Ruskin and Beatrix Potter. However, it was also during this period – a time when adventure and exploration was very much encouraged – that Lakeland also became a venue for a new recreational sport: that of rock climbing. The following story from the early twentieth century is proof that these two Cumbrian passions – mountaineering and creating and telling stories – did not suddenly cease with the end of the eighteenth century and the onset of the Great War.

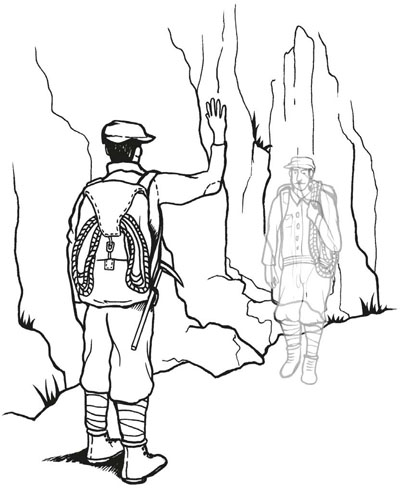

In the years leading up to 1900, two young men loved to test their skill, strength and courage together on the rock faces that grace the likes of Scafell, Skiddaw and Helvellyn. With the start of the First World War, Lord Kitchener pointed his finger and one of the pair answered the call, heading for France, Belgium and the horrors of trench warfare. His friend continued on his days off to rock-climb, although it had become a lonelier and more dangerous activity, as any solo climber knows.

One sunny day, after a particularly tough route on Scafell Crag, he was walking down a gully known as Hollow Stones, when he heard a cheery whistling. He was delighted to see the smiling face of his soldier friend coming towards him, presumably home on leave, going up to do the same route he himself had just conquered. They chatted of what they might do when the war was over. Then, parting, the pair agreed to meet up later at the Wasdale Head Inn for a pint.

The soldier never showed up for that drink. A couple of days later, the climber heard that his friend had fallen at Passchendaele, at exactly the time they had met in the beautiful sunshine of a Lakeland summer.

On the Sunday nearest to 11 November every year, people gather at war memorials to remember the dead of the two world wars. There is probably a war memorial somewhere near to you, and if so you will know that war memorials usually take the form either of a statue of a soldier, or of a column of stone engraved with the names of the dead. However, if you were to go to the war memorial in the village of Hartest in West Suffolk, you wouldn’t know you were at a war memorial unless you had read or heard this story.

For a start you’d be in the bar of The Crown, the village pub! If you investigated the room carefully, you might just spot some coins nailed to a wooden beam: twenty-four florins and a farthing to be exact. Even without any names to accompany them, these coins are this village’s war memorial. This story explains why.

In 1914, the men of the village of Hartest – and the boys who looked old enough to pass as men (and boys often did pretend they were old enough) – volunteered to join the British Army.

The night before these brave young men left to go to war in France and Belgium, they took their mothers, wives and girlfriends for a drink in the village pub. As they said their sad farewells, each woman nailed a coin to the beam, telling her man that when he returned home safely, he could take that coin to buy enough food and drink to have a week’s rest before returning to work on the farm. (Amazingly, a florin – worth about ten pence – would have done that, a hundred years ago.) The one woman who couldn’t afford a florin nailed a farthing (a quarter of an old penny).

Thankfully, if you visit this place today and look closely at the same beam, you will see that there are more holes in the wood than there are coins, one for every soldier who returned. But the fact that there are twenty-five coins remaining shows that, even in that small village, there were twenty-five good men who never returned to their families – a sad but true story.

![]()

The late Albert ‘Nabs’ Smith – a Suffolk forester from the village of Chillesford near Orford – regaled Taffy Thomas on many occasions with the following rhyme as they supped Adnams Ale in the bar of his sister Vera’s pub in Butley, The Oyster Inn.

Old Brown sat in the Rose and Crown talking about the war.

He dipped his finger in the froth and then began to draw.

These are the Allied lines he said, and this is the German foe.

The potman he called time. Old Brown shouted Whoa!

Do you want us to lose the war? Do you want us to lose the war?

To call time now it would be a sin,

Another two pints we could have been in Berlin!

Do you want us to lose the war?

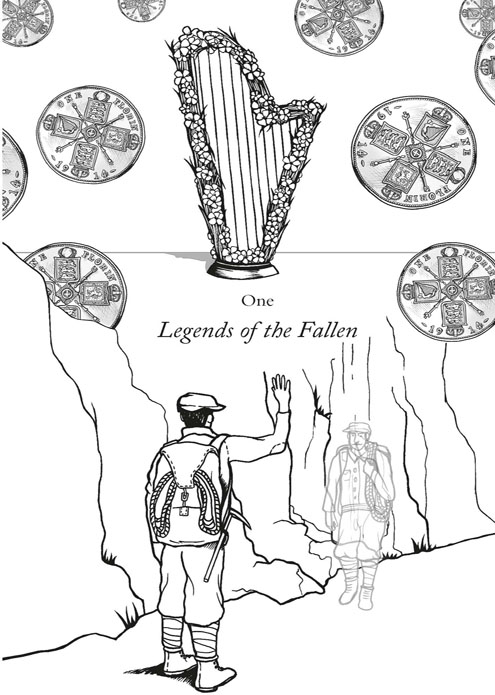

Since the seventeenth century, the people of Grasmere, Cumbria, have picked rushes from the lake, decorated them with wild flowers and paraded them through the village to St Oswald’s church on Rushbearing Day. The Grasmere parish magazine of 1890 describes the bearings as follows:

The rushbearings are varied in device; simple poles, crosses, hearts, wreaths are all common and among others have been wont to appear a tall pole with a serpent twisted about it, a little Moses in the bushes and a harp, designs which probably at one time conveyed scripture lessons or bore witness to some old legend.

Over the years the custom has attracted many different visitors and followers, one of whom was William Wordsworth, who wrote the following passage about the Rushbearing in 1815:

Closing the sacred Book which long has fed

Our meditations, give way to day

Of annual joy one tributary lay;

This day, when forth by rustic music led,

The Village children, while the sky is red

With evening lights, advance in long array

Through the still churchyard each with garland gay,

That, carried sceptre-like, o’ertops the head

Of the proud bearer. To the wide church door,

Charged with these offerings which their fathers bore

For decoration in the Papal time,

The innocent procession softly moves:

The spirit of Laud is pleased in the Heaven’s pure clime,

And Hooker’s voice the spectacle approves.

William Wordsworth (1770–1850)

The following short tale centres on a Grasmere lad who took part in the Rushbearing before going off to war.

William ‘Billy’ Warwick Peasecod was born in 1898. As a boy he became a member of the church choir at Grasmere’s parish church, St Oswald’s. Like most of his friends, Billy participated in the Rushbearing processions, carrying a bearing year after year, throughout the first decade of the twentieth century.

However, Billy’s bearing was very different from all the others. As he was of Irish descent, it was decided that the local carpenter should create for him a new bearing in the shape of the harp of David. Billy’s mother then decorated the intricate wooden structure with rushes and flowers, rowing out far on to Grasmere Lake to collect lilies.

For several years Billy proudly carried his harp in the Rushbearing. But then, in 1915, one year into the Great War, he joined the Border Regiment as a signaller. His regiment was posted to France where, on 5 November 1917, Billy was killed, aged nineteen.

No one could face carrying Billy’s harp in the Rushbearing after that, and it fell into disrepair. However, for the Millennium Rushbearing, Billy’s successors in the O’Neil family invited the local carpenter to make a replica of Billy’s harp. The bearing was decorated once again with lilies, and was carried in the parade that year by Terry and Sarah O’Neil.

As the procession passed by Taffy Thomas’ famous Storyteller’s Garden in the centre of Grasmere, this story of Billy and his harp was told in his memory.

![]()

Each and every year, as they celebrate Rushbearing Day, the people of Grasmere pause their procession at the village green in order to sing the following hymn:

Today we come from farm and fell,

Wild flowers and rushes green we twine,

We sing the hymn we love so well,

And worship at Saint Oswald’s shrine.

The Rotha streams, the roses blow,

Though generations pass away.

And still our traditions flow,

From Pagan past and Roman day.

Beside the church the poets sleep,

Their spirits mingle with our throng,

They smile to see the children keep

Our ancient feast with prayer and song.

For saintliest king and kingliest man

Today our ‘burdens’ glad we bear,

Who with the cross Christ’s war began

And sealed his dying wish with prayer.

We too have foes in war to face,

Not yet our land from sin is free,

Lord, give us Saint Oswald’s grace

To make us kings and saints to Thee.

Our garlands fall, our rushes fade,

Man’s day is but a passing flower;

Lord, of Thy mercy send us aid

And grant Thy life’s eternal dower – Amen.

Canon Hardwicke Drummond Rawnsley (1851–1920)

Arguably one of the most famous names associated with the First World War is that of poet Wilfred Owen. Born near Oswestry, Shropshire, in 1893, Owen joined the British Army as a volunteer in October 1915 at the age of twenty-two. He experienced trench warfare and would have understood how horrific conditions could be on the front line in those narrow, cramped ditches, which were often deep in water, mud and snow. Owen also saw the terrible results of poison gas attacks and himself suffered both physical and mental injuries. After a period in a Scottish hospital, recovering from shellshock, Owen returned to the war. In October 1918, he won the Military Cross for the bravery he showed in taking a German machine-gun post and using the gun he had captured to kill enemy soldiers.

It was these brutal experiences which influenced much of Owen’s writing and which undoubtedly coloured his view of the war. Once a proud, enthusiastic volunteer, he became one of the war’s most outspoken critics.

The following story is based on an entry in the diary of Harold Owen, Wilfred’s younger brother, who was a naval officer serving on board the HMS Astraea which had been sailing the South Atlantic off the coast of Africa. It was during this time that Harold contracted malaria.

The diary entry in question was written in the days following the Armistice. It is not impossible that the severe fever which can accompany this life-threatening disease caused Harold to suffer the hallucination which he recounts, but his description of it is lucid and, even if his vision was brought about by a temporarily disturbed mind, its timing was nonetheless remarkable.

On 11 November 1918, the day peace was finally declared, Harold Owen, a British naval officer, was on board ship, moored off the coast of Cameroon. His thoughts, however, were thousands of miles away on the Western Front, where his older brother, the poet Wilfred Owen, had been fighting. Harold wondered how his brother would be celebrating the long-awaited news of peace and he looked forward to seeing him again when they were both back home in England.

When the red African sun had sunk behind the horizon, Harold went down to his cabin to write some letters. As he drew aside the curtain which separated his bunk from his fellow officer’s, he was shocked to see Wilfred sitting in his chair, his brother’s khaki field dress looking strangely out of place on board a navy ship.

The stunned but overjoyed young officer asked his brother how he had got there, but Wilfred replied only with a smile. Confused, Harold repeated his question a second time, but again Wilfred remained quiet, and again he answered with only a smile.

Harold was so happy to see his brother after so many months of separation that, rather than continue with his questioning, he accepted Wilfred’s silence and sat down on his bunk, turning away as he did so to remove his cap and lay it on the blanket beside him. When he turned back to look upon his brother once more, the chair Wilfred had been sitting on was empty.

Overcome with sadness, Harold lay down on the bunk and soon fell into a deep slumber. When he woke a few hours later, he did not need to turn his eyes to the chair beside him. He knew that it would be empty, for he had woken with the certain knowledge that his brother Wilfred was dead.

Although Harold had received no official communication, Wilfred Owen had indeed been killed in action far away in Northern France. On 4 November 1918, in the final week of the war, he had been shot dead while crossing the Sambre-Oise Canal.

![]()

Knowing that Harold Owen claimed to have seen his brother’s ghost in his cabin on board ship, it is uncanny that Wilfred himself wrote the following famous poem in which the ghost of a fallen soldier appears to another.

It seemed that out of the battle I escaped

Down some profound dull tunnel, long since scooped

Through granites which Titanic wars had groined.

Yet also there encumbered sleepers groaned,

Too fast in thought or death to be bestirred.

Then, as I probed them, one sprang up, and stared

With piteous recognition in fixed eyes,

Lifting distressful hands as if to bless.

And by his smile, I knew that sullen hall;

By his dead smile, I knew we stood in Hell.

With a thousand fears that vision’s face was grained;

Yet no blood reached there from the upper ground,

And no guns thumped, or down the flues made moan.

‘Strange friend,’ I said, ‘Here is no cause to mourn.’

‘None,’ said the other, ‘Save the undone years,

The hopelessness. Whatever hope is yours,

Was my life also; I went hunting wild

After the wildest beauty in the world,

Which lies not calm in eyes, or braided hair,

But mocks the steady running of the hour,

And if it grieves, grieves richlier than here.

For by my glee might many men have laughed,

And of my weeping something has been left,

Which must die now. I mean the truth untold,

The pity of war, the pity war distilled.

Now men will go content with what we spoiled.

Or, discontent, boil bloody, and be spilled.

They will be swift with swiftness of the tigress,

None will break ranks, though nations trek from progress.

Courage was mine, and I had mystery;

Wisdom was mine, and I had mastery;

To miss the march of this retreating world

Into vain citadels that are not walled.

Then, when much blood had clogged their chariot-wheels

I would go up and wash them from sweet wells,

Even with truths that lie too deep for taint.

I would have poured my spirit without stint

But not through wounds; not on the cess of war.

Foreheads of men have bled where no wounds were.

I am the enemy you killed, my friend.

I knew you in this dark; for so you frowned

Yesterday through me as you jabbed and killed.

I parried; but my hands were loath and cold.

Let us sleep now …’

Wilfred Owen (1893–1918)

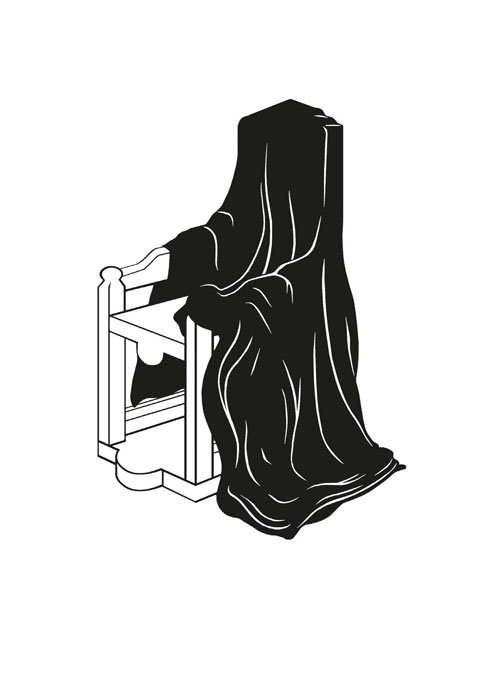

This story is adapted from a tale given to us by singer and storyteller Kathy Wallis. It tells of a young shepherd who lived near the village of Trawsfynydd in North Wales, and who became a national hero. The shepherd’s name was Ellis Evans and, as well as tending sheep, the young man was also a talented poet. He was so talented in fact, that in 1917 he was awarded the Chair for Poetry and Storytelling at the National Eisteddfod of Wales – an annual celebration of Welsh culture and heritage. Evans’ name was called out three times at the ceremony before it was sadly announced that the poet would not be able to collect his award, for he had been killed in the fighting at Passchendaele. So the chair was draped in a black cloth before being presented, instead, to his parents. The chair still exists and is on display for visitors to see in the poet’s former farmhouse home of Yr Ysgwrn.

High up in the hills of the Snowdonia National Park lies the small Welsh village of Trawsfynydd. It is a beautiful place. If you go there in the morning, you can see the sun coming up over the hills, drenching the valleys with gold. If you go there in the spring, you can see how the colours change from the harsh, dark browns and greys of winter to the fresh, green colours of spring. That’s the time when the sheep go back up the mountains, and with them go the shepherds.

If you had been on those same mountain slopes in spring just over a century ago, you might have seen one particularly talented young shepherd herding his sheep down the track and up into the hills to graze. He knew all the best places. He had learned from his father, along with his brothers. It was in his blood. Oh, how that young shepherd loved to sit up on the mountain and look down into the valleys. He said it gave him inspiration … and it did. He took the colours, the greens, the purples, the reds and the golds, and he wove them into pictures painted with words.

The shepherd’s name was Ellis Evans, and he was the eldest of eleven children. It was not always easy being the eldest of so many children; sharing a small cottage with all his siblings and both parents on an isolated hill farm. Ellis was given daily chores to do, as well as being asked to help look after the sheep.

In the mornings, Ellis would get up early and help his mother and father get the house ready for the day. He would fetch the water from the well and the wood for the fire, then he would help his brothers and sisters to get up and dressed. And when all this was done, he had to walk the mile or two down the lane to the elementary school where he was taught his letters and his numbers.

Most of the time, Ellis was a good lad, but sometimes he would be accused of daydreaming. He wasn’t really daydreaming; he was conjuring – conjuring pictures in his head and weaving them into words.

By the time he was eleven years old, Ellis was already composing beautiful poems and his teachers spotted in him a real talent. He wasn’t so good at his numbers, or his geography or his history, but when it came to words, Ellis shone.

Now, the Evans family was a very Christian family and every Sunday without fail, whatever the weather, the whole family would walk down to the chapel in the next village, walk back home again for a bite to eat and then walk back to the chapel a second time for the evening service.

To the young Ellis, the sermons seemed to go on for ever, and sometimes he’d be told off for fidgeting and not paying attention. He didn’t always want to hear what the vicar was saying either. His sermons were all hell, fire and brimstone, designed to warn the congregation – and especially the children – of all the dreadful things that would happen to them if they were not good in the eyes of God.

Hearing the vicar’s words, young Ellis was truly afraid and shook to his boots. But as soon as the sermon had finished and the hymns began, his heart would rise up once more, full of joy. The words of those hymns wove the pictures back into his life, and once again his ideas would flow.

Back then children didn’t stay on at school as long as they do today, and Ellis was just fourteen years old when, armed with what he’d learned at school and in the chapel, he set off on the next stage of his life. From then on he went to work all day and every day on his father’s farm, tending the sheep.

As he sat up in the mountains and on the hills, the colours, the pictures and the words all spun round his head and he began to write. At the end of the day he would come down off the mountain and read his poems to his friends and neighbours in the village. Listening to the beautiful words, the villagers could see the pictures exactly as Ellis had seen them in his head: the beauty of the land, the beauty of the valley, all conjured into beautiful verse.

Sometimes Ellis would talk of religion, and his poems would retell the stories that he had learned in chapel. Sometimes his poems would be about nature, reflecting the beauty of the Welsh landscape which formed his very own part of heaven here on earth.

Ellis was just nineteen years old when he entered the local Eisteddfod. He did not win, but to him taking part was pure joy. He found that he loved performing his poems and the people loved his performances. Wherever Ellis went, the people would come to hear him. They would hold their breath as he took to the stage and marvel at the beauty, the romance; his pictures of nature woven into words.

They knew him not as Ellis Evans, but as Hedd Wyn or ‘Blessed Peace’. They say Ellis chose the name one morning as he watched the sun cutting through the mist in the valley below him as he tended the sheep.

As the years passed, Ellis’ poems took on a maturity. He mastered his craft, and his poems were a thing of wonder.

And so it was that he decided to write a special poem – a poem in praise of Wales’ highest peak, Snowdon. It was a poem of beauty and Ellis was proud of it – so proud, in fact, that he entered it in the National Eisteddfod of Wales.

Once again, Ellis’ poem did not win the coveted chair, and although everybody loved it and wanted to hear more, this wasn’t good enough for our Ellis. He was determined that one day the chair would be his; one day it would be his poems, his pictures woven in words, that would earn him the National Chair.

But dark days were to come. People’s lives were turned upside down. The evil in the darkness began to spread, from one country to another, across the world. The people of Trawsfynydd didn’t think that a war across the sea would harm them or touch them in their little village halfway up the mountain, but eventually it did. The days would still dawn bright, the sheep would still need tending and there were still poems to write, but now the whole country needed their help.

The men from the Ministry came to visit and demanded that the farmers grow extra food, raise extra sheep. Then the men from the parliament in London said that all the young men had to join the war. The men from Trawsfynydd and thousands of villages like it began to march away, leaving the women and children behind.

Then the messengers began to arrive. One after the other they would come, bringing news of yet another life ripped from this earth – a friend, a relation, gone for ever.

And so the weeping began. Those left behind wept enough tears to water the earth. They wept enough tears to make the crops grow in a barren year. And all the time they wept, their young men and boys marched away to become shadows in their memory.

It was a dark morning when Ellis marched away from his village. It seemed the war wasn’t going to plan. So many of the young men who had first been claimed by the government were being senselessly slain in the mud of Belgium, that they came for the rest. Among them was Ellis.

What pictures must have been going through his head as he walked away from his beloved mountain, from his beloved valley, and away from his beloved home! No more pictures of beauty. No more pictures of romance. For Ellis was going to a world where green had turned to brown, where fields had turned to quagmire, and in the place of the peaceful sounds of sheep, birds and water tumbling over the rocks, came the sounds of gunfire and bombs. Trees that once had green leaves touching the earth now stood as stark trunks, bereft of branches. The beauty that had enshrined Ellis’ life was wrenched away and he was plunged into a world of terror and mud and blood.

Ellis was lucky at first, and after his training, he was allowed home for two precious weeks of leave. Back in the warmth of his farmhouse kitchen, he sat at the table and wrote and wrote – the shocking experience of his time at war pouring onto every page. Ellis did not stop until fourteen days had turned to twenty-one and he had turned from a soldier to a deserter. There was a knock on the door and Ellis was marched from the hayfield to the prison, and then from the prison straight to the muddy trenches of Passchendaele as a Royal Welsh Fusilier.

Amid the mud and the bloody gore of the Belgian battlefield, Ellis finished the poem he had begun back on the kitchen table in the cottage in Trawsfynydd. He signed it with the pseudonym Fleur de Lys, and on the day his completed poem was sent back to Wales, he marched to the Battle of Passchendaele.

Ellis was crossing Canal Bank at Ypres when a nosecap shell cut him down. As blood seeped from his stomach, he fell to his knees, grabbing the earth with his hands. Desperately trying to save him, the stretcher bearers ran quickly to his side and carried him to the first aid post, but it was too late. After asking the doctors, ‘Do you think I will live?’, Ellis drew his last breath and died.

When the name Fleur de Lys was called out as the winner at the National Eisteddfod that year, the trumpets sounded but no one stepped forward to claim the chair. The trumpets sounded a second time but again no one stepped forward. Then, for a third and last time, the trumpets blew, before the archdruid stood and solemnly announced that the winner, the mysterious Fleur de Lys, had been killed in action just six weeks before. The empty chair was draped in a black sheet and the archdruid proclaimed, ‘The festival in tears and the poet in his grave’.

The black chair was then carried all the way to the mountains of Snowdonia and to Ellis’ parents’ farmhouse in Trawsfynydd. And there it remains, to this day, for everyone to see so that, instead of a legacy of death and mud and blood, people can celebrate the legacy of the mountains, the valleys, the sheep and the babbling stream that Ellis loved: the beauty of this life.

Why must I live in this grim age,

When, to a far horizon, God

Has ebbed away, and man, with rage,

Now wields the sceptre and the rod?

Man raised his sword, once God had gone,

To slay his brother, and the roar

Of battlefields now casts upon

Our homes the shadow of the war.

The harps to which we sang are hung

On willow boughs, and their refrain

Drowned by the anguish of the young

Whose blood is mingled with the rain.

Ellis Evans (1887–1917)

Translated by Alan Llwyd for Out of the Fire of Hell: Welsh Experience of the Great War 1914–1918 in Prose and Verse (Gomer Press, 2008), reprinted by permission of Alan Llwyd.