18

The Conventional Musical System

Musicality and Sonority

18.1. A DELIGHTFUL ASSORTMENT

So, off with the masks: let the traditional system say what it has to declare. It names four things.

Pitch, duration: we shouldn’t ask too much of them. The manuscript papers are checked. Seven keys, that’s a lot, what a large bunch for twelve notes. . . . A half note is worth two quarter notes? A quarter note three eighth notes when they’re triplets? Maybe, as long as we don’t look too closely. After book 3 there’s an amnesty. We’ll write that down in the register of values, which will, of course, have the number 4 on it. We will remark that those pitches are pretty approximate and are often different from the nominal value, as are a phoneme’s irrelevant variants. We have already observed, more seriously, that half notes and quarter notes mark out spacing much more than actual durations: they give rhythm to silences, or at least breaks in silence, rather than to the presence of sounds. There will be no perceptible relationship of duration except within an instrumental structure or between instruments that make comparable objects (short-lived or sustained). Because we do not play in durations, we will accept the cruder value rhythm (at least in the traditional system, for there is no question of stopping there in a better researched music).

What begins to look pretty bad in the values filing cabinet is this intensity, elsewhere jealously measured in “amplitude,” here visibly abandoned to the charming imprecision of an Italianate notation, where a double superlative is sometimes needed to bail it out from its depreciation: “pianississimo.” Now, all this works admirably well, provided that we are not more demanding than the maestro himself and are not made to take nuances for decibels. . . . The musician, of course, appreciates nuances for their acoustic content (decibels), the audiological transmission (phons), and the absolutely unpredictable weight of complex sounds,1 but he appreciates them much more for the melody of weight that these sounds create with their neighbors (which is a consequence of the perception of structures). The disparity of complex sounds is such, dynamically, that a musician can only hear them through reference to their source, a pedigree that is always available to back up judgment in the same way the candidate’s youth or the weakness of his muscles is taken into account when his performance is being evaluated. Never has a drumbeat prevented us from hearing fortissimo a tiny piccolo sound. Never has a trumpet pianissimo been confused with a violin fortissimo, which is, however, a meager acoustic presence compared to the other. There remains the fourth partner, the too notorious musical timbre. This one, as we saw in the last chapter, cannot be confused with the others.

18.2. A DANGEROUS INTERSECTION

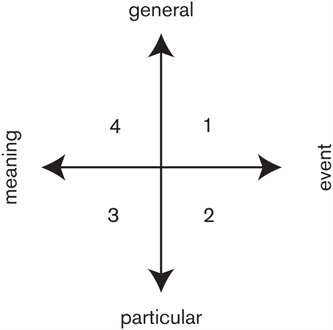

We, who had believed we could put the abstract on the left, the concrete on the right, just as we had placed the meaning on one side, the event on the other in our diagrams in book 2, what are we to think of this irruption of the concrete into the abstract, since every musical value, if we consider it rigorously, implies an instrumental quality? In the contrast we have drawn between language systems and speech, just as valid for language as for music, do we not have the impression that ultimately it is the abstract that rises to the higher sections in our illustrations, having decanted concrete sound to the bottom? And now in musical composition we are adding the generic syllables of sector 1 to the values in sector 4.

We inevitably come to the point of wondering what the abstract is, having thought it so firmly in our grasp when it appeared in the reassuring form of written signs or musical symbols. We turn once more to Lalande’s vocabulary for help: “Abstract is said of every concept of quality or relationship considered from a more or less general standpoint independently of any representation of it. Conversely, full representation, as it is or can be given, is called concrete.” We can see that the end result is two sorts of musical abstractions: one leading to values, a quality recognized in a collection of objects; the other leading to instrumental timbre, the mark of the instrument on other collections of objects. This process of abstraction is very similar to the mechanism that allows us to identify the object in the structure, except that it summarizes experience. It is “an activity of the mind giving separate consideration to one element—a quality or relationship—in a representation or a concept, giving it special attention and ignoring the rest.”

Thus the term violin, in the direction “a G on the violin,” is no less abstract than the value indicated by the symbol G. Ignoring the rest, we have retained what could be common to all possible violins.

In short, our schema is compromised. We have, in fact, tended to make it a one-way street, at least in conventional systems where the sound object is forgotten in favor of the meaning. But we cannot extricate ourselves like this without ignoring reality. The two diagrams in the last chapter, which depict a single schema of perceptual structures, have already shown this.

Thus, in every and any case we will have to make two in some way perpendicular phenomena intersect. One of them has been described many times: it is the way every sound object moves toward the two poles of the event and the meaning, the source that produced it and the message it delivers. The other is a relationship going from the general to the particular:

What can we abstract from a mass of particular experiences, going toward either pole? Where sources are concerned, it may be that instead of being overwhelmed by a profusion of disparate events, we manage to extract some general ideas that enable us to organize them, not only by sources (violin, voice, etc.) but by phonation. This is how the phonetician draws up a list of phonetic material (sibilants, dentals, etc.), which may be compared to the list of instrumental factures (friction, pizzicati, etc.) applied to various types of sound bodies.

Where sound effects or qualities are concerned, we know that they are only retained in structures of meaning. It will be even easier, once a way of using sounds is established by custom, to abstract these qualities: phonemes in language, values in music.

Thus, starting from a concrete experience, a story, or natural as well as cultural phenomena, we arrive at two concepts that can be encoded, notated, written down: these are the contents of sectors 1 and 4.

Indeed, but there is still the question of hearing. So we hear in two ways: either in reality, therefore specifically, or in the mind. If we can read, we can, by means of a text or a score, hear it in implicit or imaginary reality, which can only exist through the (spoken or sound) materials supplied by our memory. The exercise undeniably “works” better for language systems than music, and the reasons for this are immediately obvious. One is owing to the fact that in language the sound object is superseded (this is justified by the arbitrariness of the codes that allows signifiers to be easily permutated); the other is to do with the content itself of the written or musical symbols: with language systems, in any case, writing is much more reliable than in music.2 The articulatory, causal event is entirely forgotten. It should never be the same with music, where the diversity of timbres (instruments and instrumentalists) is part of the language itself. So we observe a strange disproportion between the contents of sectors 1 and 4, since 4 summarizes the very meager residue of shared formal values; in 1 a multiplicity of instruments; and for each instrument a multiplicity, not only of notes, but also of factures. This is the divergence, already mentioned, between pure and instrumental music.

This helps to explain two tendencies in music: a tendency to orchestrate, inasmuch as this allows reference to events and the active presence of instruments; a tendency to Klangfarbenmelodie, in which, out of nostalgia for pure music, there is a tendency to reincorporate timbre (here not of the instruments but the notes) into sector 4 and make them into a value, as we explained in chapter 16.

18.3. MUSICALITY AND (TRADITIONAL) SONORITY

Finally we will tackle the work in its two forms, abstract and concrete: its score where it appears in a general, virtual state, in the form of signs, and the gramophone record where one of its particular performances is engraved. Can we give a clear account of such an everyday parallel?

Not very easily. All the ex-concrete from sector 1, all the ex-abstract from sector 4, are notatable and appear on the score. Like a literary text, which potentially contains a language system and speech, even if it is only read with the eyes and memorized in silence, the “work” is in principle given, once it comes off the publisher’s press, and its unobtrusiveness would make us believe it is what it is not: a text.

This text, virtually but authentically sound, has, however, one particular quality: it brings together an infinite number of potential performances, which will all have the “musicality” of the score in common, while each has an “individual sonority.”3 . . . We can think of no better definition of these two terms.

We will now look at all the notes used in the traditional system and take stock of them. First, the normal orchestra and its usual instruments, playing in accordance with the rules of music. It is with these materials that the composer will compose his work. We will simply present him with this material in somewhat better order than usual, and, remaining at the lexical level, we will not even mention the grammars or syntaxes he will have to obey or flout. Now we can sum up our results like this, and present them in four boxes (fig. 20), which should correspond to our definitions, otherwise so vague and ambiguous, of musicality and sonority:

• In the domain of musicality we include everything that is made explicit through symbols,4 everything therefore that can appear on a score, everything, short of performance, that enables a work to be constructed. We will take care to separate the values of “pitch” and “duration” on the left and instrumental timbres on the right, sidestepping nuances or, more precisely, bringing them into play in both diagrams.

• In the domain of sonority we will hear . . . everything else. Opposite sector 4 with its values that can be symbolized, we must also mention the sonority ordinarily attached to all instrumental notes, which, one by one, take on color in their own way. This is assuming that in this left-hand part we only put (in our minds) what is general, what can be abstracted from the particularity of every performance. For example, we will know that a string sound, independently of the violin or the violinist (or the viola, or the cello) will definitely have complementary values of sonority (resonances, harmonics, fluctuations, profiles, etc.) and that some bass sounds (piano, bassoon, double bass) will have a grain, or a value of thickness, that contrasts them with different parts of the register and has practically nothing to do with particular instruments or performers. The composer knows this, and, as he orchestrates, he anticipates and uses this knowledge in advance.

FIGURE 20. Musical-sonority summary (traditional system).

Finally, in sector 2 there is a contingent residue, the only individual, ultimately the only concrete elements, that cannot be determined on the score, even by using all that its symbols contain and everything they imply. This is the margin of freedom reserved for the performance. As we have placed ourselves under the austere conditions of considering only the material, we will not even explore the virtuoso’s style, only his technique. By technique he produces notes in his own way, linked, of course, to his personal instrument; it is their particular sonorities that will appear in sector 2, to nuance, personalize, put their signature on the complementary values in sector 3.

18.4. INSTRUMENTAL OVERVIEW

This way of grouping is not easy, but it provides a framework, which until now had been completely lacking, for anyone wishing to draw up an inventory of the intrinsic characteristics of an instrumental domain, as much for use in composition as for its resources or performance margins.

How can we analyze the musical domain of every principal instrument? How can we assess, rather less vaguely than usual, and in ordinary words, what is called their musicality and their sonority, while still strictly limiting ourselves to the traditional system and its conditioning?

We will imagine that we are comparing a dozen of them in the following four ways, corresponding to the four sectors in our illustration:

Sector 4: available values, quality, and quantity. Extent and accuracy of the register, ability to deliver sounds within the code of pitch, duration, and intensity.

Sector 3: sonority of notes. Margin of coloration of the above values, additional enrichment, presence of sound values over and above nominal values.

Sector 1: instrumental timbre. General musical interest of the instrumental timbre: originality and richness of this. Permanence. Emergence of this timbre in ensembles.

Sector 2: sonority of timbres. Same relationship between 1 and 2 as above between 3 and 4. Particular coloration of individual instruments. Leeway left to the performer for personalization, enrichment, nuances.

Within the traditional system, musicians—whether amateurs, performers, or composers—have vast experience of this musicality, as well as this sonority that we have just mentioned. Teachers, like their pupils, know even better how to embark on the conquest of each of these instrumental domains—that is, what impersonal and rigorous foundations must first be laid (note values and a consistent timbre), and then what must be mastered in terms of register, color, and personality.

So many and such subtle judgments have—and for good reason—never been reliant on a clear description, and even less on a comparative diagram of the musicality-sonority complex. For it to be possible, in fact, to answer the questions we will ask, they must be perfectly well-founded and perfectly understood. In other words, we need a clear frame of reference on which the questioner and the questioned unhesitatingly agree. Developing this would demand of the author, as well as the reader, work that may well be pointless. In the absence of precision, all we can suggest is a sort of parlor game, which will be sufficiently instructive if it allows us to quantify the extraordinary complexity of the cultural references to which each one of us spontaneously relates.

18.5. WHAT IS YOUR FAVORITE INSTRUMENT, AND WHY?

Thinking about the use of instruments, not in experimental music but in the most strictly traditional music system as it is taught in the conservatories and put into practice in Sunday concerts, we will ask four questions in relation to ten instruments: six traditional instruments (1: piano, 2: violin, 3: flute, 4: harmonium, 5: trumpet, 6: voice), to which we will add a newcomer (7: ondes martenot), and three gatecrashers that have only one note in their entire vocabulary and are not therefore instruments but isolated sound objects (8: a gut-wrenching grating noise, 9: a complex electronic sound, 10: a gong sound).

The first question concerns the emergence of timbre: classify these ten instruments—or isolated sounds—according to their ability to stand out clearly in an orchestral ensemble, to be distinguished from the others both by differentiation and the originality of their own timbre.

The second question concerns the emergence of interpretation: classify these ten instruments—or isolated sounds—according to the opportunities they give for the instrumentalist to express his personality (or in other words, according to what the facture of the objects they come from can reveal about the talent and sensitivity of the instrumentalist).

The third question, not to be confused with the previous one, concerns the emergence of the sonorities that, as we have just seen, we consider to be independent of the interpreter’s playing, his particular instrument, and values properly speaking. (The gong, for example, will have no register of values and will give hardly any margin for play. Conversely, its sonority will be indubitably richer than a piano note, beyond any musical notation in sector 4.) So classify the instruments according to their sonority, depending on whether this adds to the nominal values.

The fourth question is the most classical, and question 3 is related to it: classify these instruments according to the accuracy, the clarity and the refinement of their register, with reference to the nominal values of the traditional system.

This is all about assessing the instrumental qualities we have learned to identify: in the first and fourth question, those that give a guarantee to the composer; in the second and the third, those that provide reciprocal pleasure for the listener who enjoys virtuosi and the virtuoso who enjoys instrumental techniques.

In suggesting an exercise such as this to a group of people, we will stir up a lot of arguments and often come up against hesitation to the point of refusal to reply. For what it is worth, here is our personal contribution, which will at least shed light on the meaning of the questions.

First question: First, very obviously, come the grating noise and the electronic sound, which are far too recognizable. Then the ondes martenot because of its novelty in the orchestra rather than its intrinsic originality. Then the gong, this time for its originality. Then, in order, we would place the voice, the piano, the violin, and only after these the trumpet and the flute. Last by a long way, the harmonium, which has little chance of standing out in an ensemble.

Second question: Clearly, the voice and the violin give the musician the most leeway, followed by the flute, the piano, and the trumpet. The ondes martenot gives fewer opportunities for personalizing the sound, the harmonium and the gong hardly any at all. The two fixed sounds (grating noise and electronic sound), of course, give none at all.

Third question: The grating noise and the gong add most to the values recognized by the system and are therefore likely to “unbalance” it: the disproportion between this added value, sonority, and the nominal value is huge. The complex electronic sound, about which we are told very little, is doubtless not far behind. Then the ondes martenot and the voice, which we know can give a very different timbre to every note they make (we are talking about something quite different from general timbre, which refers back to the instrument). The violin comes immediately afterward. With the piano, the trumpet, and the flute the margin for coloration, which is there, is clearly more limited than in the previous cases; finally, for the harmonium, it is close to zero.

Fourth question: At the top is the ondes martenot, the grand champion of values of all types, continuous or discontinuous, chromatic or tempered, in the most extensive register, capable of guaranteeing durations, as well as nuances, with incomparable accuracy. Far behind, with less formal reliability and breadth (but also with the resources for chromatics, sounds sustained in duration, and subtlety in pianississimi), comes the violin. Then, the instruments tuned to a temperament, to the discontinuous and sounds that are sometimes short-lived: among these the piano comes first, because of its reliable and extensive register, with which the flute and the trumpet bear no comparison. Only then, the voice. Having made much of it elsewhere, here we must recognize its weak points: a restricted register and unreliability in relation to values. We will give low marks to the gong and the electronic sound, as very poor pupils, but with more or less indulgence depending on whether they are locatable in terms of the tonic or only in terms of color. No marks for the grating noise (or 1 at a pinch if, like its fellows, it places itself in an area of the register, with a minimum of discipline). In these last three cases the classification makes hardly any sense, given that we are no longer assessing registers but isolated objects. We will see that the latter may either approximate—roughly—to a note or—more probably—merge with other bass or high notes, which certainly achieves nothing in the “system.”

In figure 21 we played around with transferring this classification of the ten above-mentioned instruments, based on each of the four questions, on to the four diagonal lines in the figure. By joining up the resultant dots, we obtain a sort of contour for each instrument. Quite well balanced for the piano, which has a very honorable ranking throughout, this contour takes on the appearance of an irregular quadrilateral with the highest point at personalization for the voice, or objective performance (in relation to nominal values) for the ondes martenot or the harmonium. The violin covers a large and well-balanced area, whereas the other instruments only cover smaller ones. Finally, as may be expected, we find the invalids (in relation to the traditional system), which hardly go beyond the timbre-sonority diagonal.

FIGURE 21. Sonority and musicality of instrumental domains.

18.6. IDENTIFICATION AND DESCRIPTION

Even if the complementariness of musicality-sonority is obvious in music, we have just described it from the outside based on the de facto situation of the score and the performance. We can go back over these ideas, which we will now place on a higher level in order to explain them more fully and link them more clearly to the fundamental phenomenon of structuring.

We have already described in section 17.5 the various ways in which the object may appear: an isolated sound object, heard as an event (as in a piano work by John Cage), or for its particular meaning, grouped objects forming a structure, and so forth.

To come to firm conclusions within the traditional musical system, we must take another look at the processes we have described. As soon as we hear the notes of a melody, our conditioning makes us name them, and all the more so if we are musicians. Otherwise, if we were more amateur—or uncultured—we would be completely unable to name them, or we would perhaps hear differently. And better? No, not better: with an ear that is less accurate, less refined, less “intelligent,” as sound engineers say, but perhaps more naive, more sensitive to what would be a novelty for it, which it would start by “tasting,” as it would not be able to understand. For the musician, in his system, every act of melodic listening is not to describe the notes but to identify them. This done, he will ask for them to be played again, more slowly (“Stop on A-flat,” says the teacher), to “taste” the object this time, to hear it outside the structure that identified it but did not allow it to be described. Hearing this note again, he can, all over again, identify its component elements, pick out the attack, the continuation, the decay, the vibrato, and so forth. This time he will only perceive them, name them—not describe them. It is by isolating this fragment of object (this feature,5 as linguists say), repeating it, reexamining it, that he will seek to describe it and naturally as a structure, doubtless the smallest he can isolate. All instrumental teaching is familiar with, or at least practices, this type of analysis.

Conversely, we go up the descriptive chain. This feature describes the note. The notes describe the melody, and so on.

Now we move on to timbres. In an orchestra the various instruments contrast with and differ from each other: instruments have left traces in the memory, and this is how we can identify one of them, among the others, or on its own. To describe it, we have to compare different examples of the instrument and form a structure of the same timbre, which will reveal the timbre of the timbre. These (what we have called sector 2) comparisons must not be confused with the note-by-note comparisons in sector 3. In 2, various pianos are compared. In 3, various notes from any piano are compared. This is irrelevant. The latter piano is concrete, the overall sonority of a particular piano compared to others. Comparing piano notes in general amounts to abstracting from all pianos a value added to all of their notes. The proof of this is that the notes from various pianos in general all obey the laws of the invariant described in book 3. So we can more easily see what the sectors are for. Earlier, they simply seemed to be a convenient set of drawers to evaluate the musicality-sonority pair. Here we see that they are part of the effective working of the “system.” We identify, nominally, in sectors 1 and 4. Then we qualify in 2 and 3, either to complete the description of particular sonorities in 2 or to discover more general criteria of sonority 3. Once sector 3 has been explained, new musical values emerge (in 4). Thus analyzing sonority would, if possible, use up the contents of timbre (1) and values that elude formal musicality. If the analysis could be taken to its limits, only what is abstract in music and what is concrete in sound would remain, in the pair in the two sectors 4 and 2 alone.

18.7. DIABOLUS IN MUSICA

Systems, just like civilizations, develop, live, and slowly die while undergoing change. We should say straightaway that it appears particularly futile to claim to pull one system out of our hat and that this is not our intention. We know, however, that no radical change can take place without questioning the whole system, not revising it. Besides, every development makes its impact, focuses on a certain level of language, and stays there as long as this level is capable of dealing with reorganizations and extensions. The first to be attacked are the higher levels, more accommodating, where the aesthetic quarrels of ancients and moderns are finally settled to the satisfaction of all. That is what used to be done in our music.

One does not have to be a great scholar to diagnose the present situation: the crisis is much too serious, calling the very foundations of the system into question. We are not here to complain about this or rejoice in it, and doubtless it is in no one’s power to hasten or slow down the course of events. It is, however, very pretentious and quite absurd to jump on the bandwagon of innovative, exclusive, self-assured systems when we are in a period of change and when, desperate to escape from an ancient system, people daily use its material, its notions, its methods, and, above all, an antiquated symbolism that conceals whether the value of signs is immutable or can be changed.

The crack, in any case, is clearly visible, and the fissure cannot escape anyone at the frontiers of the musical and sound. Contemporaries often make sectors 2 and 3 on virtuoso playing and eccentric sounds carry the burden of their innovations. Without good virtuosi using their instruments in unusual ways, providing effects way beyond the directions on the score, without the competition, this time creative, between players and their conductor, the work is worse than badly played; it does not exist, by which I mean it is not realized. The audience, often disappointed with so much “speech,” looks for “a language system” that is absent. So what is going on? The frame of reference 1–4 has been superseded, it is no longer note values and timbre that count; the score is no longer an analytical score that gives an account of the work but an empirical score, entirely performance-based.

We will take some more specific, simpler examples and bring the ondes martenot into the orchestra. While paying tribute to this excellent invention, we cannot but acknowledge that it undermines the “system”; it muddies the waters in an apparently benign way but is indicative of catastrophes to come. In vain do we wonder about its nature. The papers are in order—an extensive, accurate, and nuanced register: timbres, which can at will be made meek or rebellious, concealing themselves turn and turn about through mimicry, yet remain ready to give a “helping hand” where colleagues fall short for lack of breath or register. It is too good to be true. Those cunning craftsmen who have been polishing up their tools for centuries, humble servants of a grand duchy fastidious about correctness, see it coming in its great clogs, the electrical device that can do anything, the vanguard of electronic or concrete hordes. . . . Is this too far-fetched a sketch?

The ondes had, however, done everything it could to seek inclusion and forgiveness. Consider the gong, infinitely more brutal. And the cencerros, comical and loose-living. These are, strangely, looked upon more kindly, and people allow themselves to be intimidated, corrupted by what laughs in their face. Doubtless, they were expecting the gong to be rarely used, that it would settle for playing the final cymbal clashes in a symphony, more gravely, more piously perhaps (wasn’t it brought up in temples?). Here there are several of them. And each one acts on its own behalf. Who would believe in a keyboard of gongs? Messiaen, at Chartres,6 for a moment makes as if he believes in one. Stockhausen does open-heart surgery.7 . . . We must endeavor to make the roll call of our defensive sectors. In fact, it is not enough to say that each gong is located in sector 1 and its sounds in sector 3: we can see that the system is in disarray in two ways. We are no longer dealing with systems of structures but the perception of an isolated structure-object. As an instrument, it is off-key in sector 1. As an object it holds sway in sector 3 without bothering about values, and all we are left with is its presence (is it in 2?), without our being able to attach its sonority to a formal or complementary value. The system, if not completely destroyed, is at the least threatened by a foreign body.

The gong only disrupts the system so seriously because it suggests another system, whereas we might have thought it was simply an ambiguous case, an exception to the rule.

Other instruments could make us hear intercalated “wrong” notes or badly tempered keyboards. They would still remain within the concept of instrument; they would have a generic name in sector 1, and it is difficult to know what is most to be feared: sector 3 upsetting the balance of sector 4 because of the strangeness of the sonorities, or sector 4 being disrupted by unusual calibrations. Such systems may therefore oppose each other, be superimposed on each other, or fight each other; but they are still the same type of system, like two related civilizations, two homologous types of writing or language. But it is difficult to compare a population to a family, a language system to a cry, a city to a standing stone. In short, the gong, even if it is compared in the mind or the memory to other gongs, tears the orchestral system apart, and we need the amiable hospitality of contemporary laxity to enjoy this bombshell, this huge spelling mistake, and immediately bedeck this idol with garlands. . . . This gong comes to us from elsewhere. It stands out, a solitary sound object. You can hear nothing else apart from it. We try very hard to make it fit in with what is around it; it forms a musical structure only when it pleases—that is, if it pleases to sing along with it. This gong is not in a situation of its own: it is the situation of every more or less suitable sound object that is invited to make music within the system. It does not work.

When sound precedes the musical, the stakes are down. The system is turned on its head. Rather than ducking the issue, cheating, composing, we must resolutely look to the sound. To our very great surprise, instead of what we thought were formless noises, we find a system—antagonistic, no doubt, but perfectly constituted. That really is something.