21

Musical Research

21.1. FUNDAMENTAL RESEARCH

In this section we are not going to try to redefine research into music. This whole work leads in this direction by endeavoring to demonstrate a practice rather than a theory and to limit rather than extend objectives. We think, however, that we should justify the fundamental phase in a piece of musical research.

We know that in science this term, apart from any direct application, denotes the exploration of basic principles, the possible revision of premises and the clarification of methods. In suggesting that the study of musical objects should come before the study of the way they are used (writing music, composing), we are likely to surprise some and discourage others. For the former this type of research is ultimately only justified at the level of language, and the most serious researchers may doubt that we can stop halfway, as it were. For the others, notably composers, this type of research goes against their instincts, which are to work directly toward music, any intervening theories (nowadays so frequent) being for the most part only aesthetic pretexts, trompe-l’oreilles, and hardly ever going right down to the level of the fundamental or the elementary. In both cases we must ask these preliminary questions: What materials is music made of? How much of these materials do we perceive? What part does our conditioning play in what we do perceive? What, beyond this conditioning, is the potential of sound, in relation to both the physical properties of the objects and the properties of perceptual structures, which man, naturally gifted, can seek to develop?

This is fundamental research, which we said should be inseparable from musical experiments at the level of language, and experimental works, which we should prefer to call studies, “experiments just to see.” We do not think the necessity of this fundamental research can be denied, any more than a traditional musician would reject music theory or would claim immediate access to composition without it.

The aim of the present chapter is to give a general outline of the program for this fundamental research. So it forms a conclusion to the preceding chapters, which are its premises; it is an introduction to the last two books, which put into practice the theories defined in the proposals for a generalized theory of music. We must repeat that this work represents an initial approach and outlines a research program for the future rather than being a summary of definitive results.

21.2. INTERWOVENNESS OF LEVELS OF COMPLEXITY AND SECTORS OF ACTIVITY

Nothing appears so simple as the concepts of timbre, melody, and value, deduced from current experience. Nothing is so tricky as attempting to establish their foundations, as we wish to do, by trying to distinguish what may be natural or conventional in musical activity.

Gestalt psychologists discovered their theory precisely by emphasizing the permanence of melody across its instrumental or transposed variants. What is natural or cultural in such a simple experience? Do we need a piano to demonstrate this? Is it common to East and West, civilized and primitive man? This elementary problem can be extremely challenging: it conceals several other embedded problems.

The division into “sectors” has already shown us how to separate out what comes from the four cardinal points of musical or sound activity. But this “diagram,” already loaded, comes into play at every level of complexity in a sound or musical chain. We have applied it (chapter 18) at the level of musical notes. This is already a highly expert usage. As for the listener, he instinctively applies it at the level of musical phrases or virtuoso passages in the course of listening. Later, if he tries to remember, his memory will doubtless function at a higher level of complexity: the work as a whole, the performer’s style . . .

We will endeavor to sum up the parallels between various levels of spoken and musical discourse mentioned above.

Limiting ourselves to a reflexive analysis “from the meaning” starting from the higher levels of complexity (the easiest for ordinary listening), we find the following:

utterances in language |

pieces of music |

|

phrases in language |

musical phrases |

|

words from the lexis |

melodic or rhythmic intervals, chords, motifs, etc. |

|

phonemes (distinctive features) |

values (pitch, intensity, timbre, duration) |

But we know all this requires training. This way of proceeding does not in the slightest help us to make a reverse analysis—that is, a synthesis building up from the elementary levels. This should be the aim of fundamental research.

So we will complete this list with other links in the chain, from research activities or comparisons that are completely absent from the parallels above. First, between words and phonemes we will insert the syllable, the phonic object (in our sense, but which has so little sense in language that it is not even considered). Similarly, between intervals (or motifs) and values we will insert the sound (or musical) object: for we must recognize the existence of an object that carries these values. Finally, we will add two lines that, in any case, are of a level of complexity no different from phonemes:

L1 utterances in language |

pieces of music |

|

L2 phrases in language |

musical phrases |

|

L3 words from the lexis |

musical motifs (chords, intervals) |

|

L4 syllables (phonic object) |

sound objects or musical object (instrumental note, for example) |

|

L5 phonemes (pertinent or distinctive features) |

(music theory) values |

|

L6 phonetic features |

sound criteria |

|

L7 acoustic parameters |

acoustic parameters |

We should again emphasize that the last three lines are not in decreasing order of complexity but represent the selection of elements of equal complexity coming from different intentions, with a view to building up the higher-level structures.

21.3. PREPARATORY EXERCISES

We have already applied the experimental method to the conventional system; in effect sectors II and III (see illustrations below in sections 21.4 and 21.5) raised their own problems. In sector II we focused on factures; we practiced comparing pizzicati, bow strokes, and blowing, independently of the violins or metal sheets, trumpets or harps to which they belonged. We did not go very deeply into this study, which at the more advanced levels leads on to the characteristic features of a way of playing, an interpretation, a virtuoso. Of course, this very complex sector II would deserve a treatise of its own. We must keep in mind that we compared objects at quite an elementary level to see the emergence of new pertinent features, which are nothing to do with musical identification. Not that a well-executed bow stroke, tonguing, or vibrato are not important in music, but they serve to qualify the sonority and are not the basis of the musicality. These comparisons have been made implicitly (but it would be better, in future, to recreate the circumstances in which they were made, even from memory), by grouping together objects that no longer have anything in common, neither timbre nor values. In comparing only bow strokes, thuds, attacks, we were studying what might be called the criterion for instrumental factures: the gestural typology that governs the vibratory processes of sound bodies. This means that we substituted a new sector 2 for the old sector II, to accommodate different forms of structuring and grouping.

As for sector III we tackled it head-on when studying the notes of the piano keyboard. This time, we were going down to the most basic levels, neglected in musical listening, to values and timbres, but not to the sonorities of these values or timbres. We were making new comparisons between levels L4 and L6, with a collection of sounds marked out by a register L5 but examined differently; for from that point we refused to consider timbre, as it emerges crudely at the higher levels of causality, as an instrumental constant. Comparing one piano note with another accelerated or slowed down until it reached the same pitch, we discovered, this time, the criteria for the note, features ignored because they are not properly identified, though perfectly well perceived. In other words, we were undertaking a musical description of the note now considered a structure and elucidated by means of the elements on the lower level L6: the morphological criteria.

Without these preparatory exercises, we should be ill-equipped to tackle the systematic generalization that is our aim. First we will draw on them to discover the rules for identifying the object at the level of sonority.

21.4. HOW THE EXPERIMENTAL SYSTEM WORKS

How do we identify sound objects? We have already given the answer: the most naturally in the world, through a mechanism absolutely identical to the one mentioned above, which is the basis of sector I. At the more advanced levels of languages, it seems to us quite natural (although, as we have pointed out, this naturalness has to be learned), to identify the bird by its trills, the wave by its breaking, the engine by its throbbing, and so forth. This is far from being an analysis of logatoms,1 and it is certainly not a general way into sound: it is the recognition of a superimposition of parallel sound chains, which, of course, include those of speech, which themselves, in every language system in the world and all possible codes, rest on the same phonatory material, which can be written in international phonetic script but not without considerably muddling the meaning of the text.

These are indeed the two extremes whose influence we should dread: the two extreme levels, one too advanced, Level 2–Level 3, enabling speakers to be recognized by their natural or conventional languages, the other too elementary, Level 5–Level 6, applicable only to an even more specific domain of sound than the domain of music, such as the sonority of speech (phonic objects).

We must place ourselves at an intermediate level, where the meanings of languages are forgotten and instrumental domains, including the phonetic, are not yet specialized. But the latter can serve as an example, or at least point to a method. It is at this (syllabic) level L4 that we placed the instrumental note in the traditional system, and where we now place the elementary sound object, into which eventually the most complex sound chain will be resolved, just as words resolve into logatoms, not now for linguists but for telephonists.2

We have already noticed that the sound universe appears to obey the same laws of articulation and stress, provided we stick to generalities and interpret these criteria very broadly.

Here our experiments with the former sectors I and II will be of use. The factures of a gestural typology, in the new sector 2, could be a first criterion for identification and therefore also for classification of all sound objects. As for what we learned from sector III, we can conjecture that, beyond timbres or short of musical values, there is doubtless a fairly general morphological criterion characterizing the stress of sounds in the new sector 3.

We can see that here, also, generalizing musical experience leads us to a very different system. We replace the timbre-pitch pair in the old sectors I and IV, used to identify musical objects, with an articulation-stress pair in the new sectors 2 and 3, a first step toward a typomorphology that should enable us not only to identify but also to classify, and hence select, sound objects. What we lose in rigor, nuance, and musicality, we will gain in amplitude and sound dominants in general.

Thus, in future we will not accept objects from specific instruments, carrying sector I timbres (which we also forbid ourselves to describe, prematurely, with conventional sector IV values), and we also refuse to accept them already grouped according to their natural sources. Faced with so many disparate objects, totally without grouping, without their conventions or their natural patrimony, a classification, even approximate, is essential, a sort of “grid” completely replacing instrumental tablature or the natural repertoire of noises. For how can we study an infinity of sounds that are not identified in any way? We will therefore use “sound identification criteria.” They will give us the means to isolate sound objects from each other, since we refuse to do this through the usual sound or musical structures. In addition, they will lead us to a practical classification of sound objects, an obvious prerequisite for any further musical regrouping.

Finally, we must recognize that this search for criteria for identifying sound is not without musical bias.3 More precisely, since we do not wish to make premature judgments about music in general, we admit to a deliberate but specific intention, as musicianly as it is musical. What are these two so simple and, doubtless, so obvious decisions that we have taken years to make? We will not make the reader wait until he has read the next books, where they will be dealt with at length, before arming him with these two lamps to lighten the way: the (syllabic) articulation of sounds seems to us to relate fairly well to the character of their sustainment; the (vocalic) criterion of (vocalic) stress appears to be fairly well linked to intonation, to the fact that sound is fixed or variable in pitch, or that this pitch is complex or harmonic. In other words, by combining the typology of factures and the morphology of stresses, and retaining some of their criteria on both sides at the two poles of the object, we obtain an indispensable key to sonority, not at all sophisticated but with a bias in favor of music, as limited and as justified as possible.

Of course, we must not confuse sectors 2 and 3 on the origin of sound in a more general system with sections II and III in the earlier traditional system: the contents and the comparisons are no longer concerned with the same material. Figure 23 illustrates the definitive and comparative summary of the two systems.

FIGURE 23. The traditional musical system.

21.5. CONTENTS OF THE TRADITIONAL SYSTEM

Although we have already given a rough idea of this several times, this time we will explore it more fully, to make a definitive comparison between it and the experimental system. Its contents are in the four corners of our summary illustration (fig. 24).

FIGURE 24. Program of musical research.

Sector I. Identifying timbres (concrete aspects of instrumental sounds in general).

Two questions arise from the conventional instrumentarium.

I. Identifying one (instrumental) timbre from other (instrumental) timbres.

Ia. Identifying various notes in the same timbre.

Sector II. Describing the sonority of particular timbres (specificity of the concrete aspects of performance).

II. Describing one instrumental timbre among other examples from the same instrument.

IIa. Describing various (identical) notes from the same instrument in other performances (performance timbre).

Sector IV. Identifying values (the abstract in general).

IV. Identifying the value of one (identical) note in various timbres: pitch, duration (?), intensity (??).

IVa. Identifying the values of different notes through reference to calibrations (melodic, rhythmic, dynamic).

Sector III. Describing the sonorities of instrumental notes (the concrete aspects of notes in general).

III. Describing the sonorities of the (same) note in various timbres (in general instrumental).

IIIa. Describing the various notes in the same timbre (in general instrumental).

Remarks.

These questions make four pairs that, on the figure, match four relationships of permanence-variation or, again, similarity-difference.

We find:

I and II: That the same instrumental timbre is musically identical with the timbres of other instruments and that instrumental examples of the same timbre are different (in sonority).

IV and III: That notes of various (instrumental) timbres are (musically) identical in value, and various (instrumental) notes of the same value are different (in sonority).

These two pairs, going from the top down (musicality to sonority), describe respectively the sonority of the timbre identified among timbres, and the note among notes of the same value.

We also find:

Ia and IIIa: That the timbre of notes from one instrument is (musically) identical, and the timbre of each of these notes is different (in sonority).

IVa and IIa: That a structure of values is (musically) the same while their various performances are different (in sonority).

These two pairs, diagonally (musicality to sonority), describe the sonority of the notes identified by having the same timbre or the same structure of values respectively.

It can be seen that the identification-description relationships systematically refer back from the explicitly musical to an ill-defined sound material. It can also be seen that the traditional system, however simple and rational it may appear, raises eight interrelated questions that are, moreover, entirely to do with means of performing.

21.6. ORIGINS OF THE EXPERIMENTAL SYSTEM

How can we simplify these eight questions, on the one hand, and find greater independence between the musical and its instrumental means, on the other?

First of all, we can see that these eight questions are to do with the fact that the traditional system complicates itself by grouping notes at the level of the instrument. Along with its investigations into general values, it pursues investigations into timbre, which always have a double meaning: we never know whether we are dealing with the timbre of the note, which involves an additional description of value, or the timbre of the instrument, which involves a particular grouping of notes or a manner of performing them.

Is it possible to do without the specificity of the instrument? Yes, provided we no longer expect to find notes nicely grouped by (instrumental) timbre. But if there is no longer an instrument, there are no longer any notes either. It would be simpleminded to imagine that, in losing the instrument, we do not also lose notes—that is, the registers of values that it enabled us to identify, in addition to its timbre. Conclusion: if we abandon traditional musical identification, we must find another system in the free-for-all of sound because we are no longer guaranteed anything: neither timbres nor values.

If we do then manage to identify objects in sound, we will have to analyze them musically—that is, describe them.

We will imagine the problem is resolved, and reexamine the four pairs of questions we have just put together. Using a degree of wordplay, we will imagine that the word timbre, by extension, refers to the most concrete aspect of each object, its properties as a whole, the fact that it is itself: its character, a more precise term than timbre. And that the word note refers to what is most general in objects, their shared properties as a whole: a criterion, a more general term than value. If the problem has been resolved, this could only have come about through a series of approaches, since our starting point is the generality of sound objects. Could the four pairs of questions above be taken up again to illustrate the passage from sound to the musical in four phases? As we are going from back to front, we should start with the last pair.

Questions IVa and IIa. Here we are comparing what is most disparate: a particular performance and a note value. Now the question is to find the starting point for a principle for identifying objects. Is it reasonable to ask the seemingly most sensitive question (and the most delicate: the facture of the performance), just when we are embroiled in the universe of disparate objects? Indeed it is: it is from the concrete that we must now start, but on condition that all we want to do, at this stage, is sort through it very approximately. The requirement is reversed. Instead of a delicate judgment about facture, we will retain only elementary criteria, common to all sound factures in the world. Instead of quibbling over values, we will be content with rudiments: whether the sound, for example, is fixed or varied, complex or harmonic. These questions, intersecting on an elementary diagram, give us a grid with two criteria, which will lead us to a typology: a means of grading, from which sound material will emerge labeled according to (musical) types of (sound) objects.

Questions Ia and IIIa. If we turn for a moment from the sound body and its specific timbre and focus solely on the difference in sonority of the “timbre of each individual note,” we are comparing the sonority of these notes (as we did with the piano, taking no notice of values, which are now only numbers for ordering objects in a collection that is being studied for something else). A study of the sound forms or formal qualities of the objects examined in this way, without any premature consideration of calibrations of values, is a morphology. From it emerge criteria, distinctive features of the form of the objects (their identification underpinned by the morphology), some of which are described as musical, if we judge them suitable for the musical, or at least interesting enough for us to pursue a procedure for describing them. We will suppose that in this way we did find rules for identifying types of sounds and criteria for the perception of sound. We have still done no more than apply a musicianly ear to the totality of sound objects. We still need to describe these objects musically.

The pairs of questions above (I and II, IV and III) are no longer relevant, as they are based on particular instrumental groups. We may have to revise the way the questions intersect, giving the word timbre the generalized connotation we have adopted. In this case we must transpose a little.

Pair II-IV, which should read like this: do these timbres (these sound objects) produce the same type of note—that is, do they give a structure belonging to the same criterion? Is this criterion (which has scarcely any chance of standing out as a value in the disparate mass of timbres) perceptible to musical awareness and how? This is a form of musical analysis that aims first to describe a certain criterion and then to see if it can be incorporated in a calibration.

Pair III-I. If various timbres produce the same note, it is because, on this occasion, the fundamental timbre-value relationship has been achieved. We have described musical structures, from objects we know how to describe, then produce, and which then emerge as values. We have achieved the most general syntheses of the musical.

21.7. INVARIANTS IN THE EXPERIMENTAL SYSTEM

Figure 24 will practically govern the plan of all the rest of the work. The reader will therefore need to refer back to it. Like all syntheses, this one will only be useful once some of the many relationships it regroups have been tested out.

The basic axiom is still the same: a collection of objects displays certain similarities and certain differences. Whether we are dealing with the formulations of linguists (Jakobson’s rules) or the first discoveries of a particular musical invariant (the latter varies in the collection, provided that the former remains constant), we always come back to the same somewhat paradoxical stumbling block,4 which may, if we are not careful, sometimes be expressed as follows: “What varies is what is constant.” Thus, the timbre of an instrument seems constant to us, but this is only if we find other timbres and observe that these timbres, in fact, vary from one instrument to another. Similarly, pitch appears as a constant value in a particular note in the melody but only if other notes also have a pitch and serve as a foil. Now, immediately, we can see that timbre is dispersed into notes (of the same timbre), each of which has therefore not only a pitch but also a timbre. In the same way that criteria including harmonic timbre, dynamic profile, and so forth are dispersed from a single note with a pitch, similarly, what was previously identified (that is, perceived as fixed and linear in a varying context) now appears as described; that is, its earlier fixedness and how it was identified (as a value) are no longer of interest to us, but the problem now is its complexity, which is revealed through new processes of identification, at lower levels, of the elements of which it is itself composed. Here, of course, we recognize the object-structure chain, and the two successive processes of identification (on the higher level) and description (on the lower). Was it necessary to say this yet again? Perhaps, for as often happens in mathematics, as well, a very simple axiom conceals many implications, which we will develop in detail in the next seven sections.

21.8. SUITABLE OBJECTS

This caricature of a formula, “What varies is what is fixed,” elicits the usual shrug of the shoulders. A pitch structure reveals the value pitch. The tautology is only apparent.5 The word pitch is used here in two senses. One is the characteristic attached to the object. The (harmonic) notes that are (implicitly) supposed to form the melody are very specific musical objects, and their essential property is, in fact, to present a pitch. As a result they can be put together to reveal a pitch structure in a second meaning of the term, as a value and, indeed, after this, a calibration of pitches, in a third meaning. This value of the object, now forgotten as such, becomes only a quality with a structure that allows of abstraction. This is the only quality of objects in a structure that we will retain. We will imagine three situations by way of illustration, then a fourth. We have a cymbal, a triangle, a piano, a gong, a violin, and a trumpet. Some of the sounds produced by these instruments have the characteristic of pitch; others do not. They are not suitable for the experiment. They cannot form a pitch structure. Second experiment: piano, violin, and trumpet notes. Despite the disparate nature of the objects, they share the characteristic of pitch. The experiment works, but attention may be divided. This is not how we would proceed with a child, a beginner, or a primitive man to make a value appear. Third experiment: we take notes exclusively from the piano or the violin. It seems now that only the pitch changes, thanks to a constant timbre. We know what to think of this timbre, so inconstant, which itself requires identification and description. We also know that each note possesses its timbre and that it is not only the value pitch that changes from one note to another. But there is indubitably a reinforcement of perception. This collection is the most suitable. It is clear to the child, the beginner, and even the outsider from another musical civilization. The fourth experiment, altogether different, and which, beyond traditional theories, is at the basis of musical theories, is calibrations. So we have three levels of comparison between objects, simply for a value to emerge: unsuitable objects, because they do not have this characteristic; objects that are just about suitable, because they have this characteristic, but among a totally disparate mass of other characteristics; and, finally, very suitable objects (for music, let us not forget, therefore musical), because of the not necessarily simple reinforcement of the perception of a value through the nature of the other characteristics, which make this one appear special, dominant. And above all, we must be sure to separate this phase of identifying a value from any description of the same value using intervallic relationships related to calibrations.

21.9. PERCEPTUAL FIELD

In effect, in the above experiments we were, it seems, working only with the properties of objects, revealed by their structures, and we scarcely went beyond the descriptive. In fact, we could divide the melodic experiment in two, as we did with questions IV and IVa. This is where the play on words “What varies is what is fixed” is resolved. We determine what is constant, that is, the perceived property that enables us to identify this characteristic through a more limited, but more convincing, experiment: unisons in several timbres. Then, once we have found out about this, we focus on something else: the relationship between values this characteristic can assume, the interval these values give, and whether this relationship has a meaning. So these particularly suitable objects lead to a new experiment, quite different from the three earlier ones, concerned with describing this relationship, even evaluating it relatively, even evaluating it numerically through a calibration in degrees. This description can therefore be either all-embracing and instinctive (by analogy with other, not necessarily musical, perceptions: we do in fact say grainy, velvety, hollow, bright, etc.), or else we can order them (putting them roughly into a series), or, and this is the best, locate them in a calibration with relationships that are cardinal, not just ordinal, and even arranged in their field in the form of vectors.

21.10. OBJECT AND STRUCTURES

Until now we seem to have made no hierarchical distinction between these two related perceptions of the same object, except to note the paradox that if the object is identified at the higher structural level to which it belongs, we remember only one of its properties. It is only when it has been extracted from this structure that its true self appears; but, immediately, if we want to understand it, we must explore this unit, break it down in turn into components that explain it on the lower level, and describe it, components that the object, now taken as a structure, enables us to identify.

By dint of being moved back and forth from its function in the higher-level structure (where it is changed into a value) to its resolution at the lower level (where it is analyzed into criteria), the object seems finally to be spirited away and reduced to the purely formal series of movements between one level and the other. It is time to stop confusing the scaffolding with the monument. This commonsense remark can be backed up as follows.

The object, if we now intend to stay on its level, leads to two sorts of problems. One of these is analytical. The same object can in fact be transferred from one structure to another on the same level. If it is identified in one of them, how will it appear elsewhere? It will, we know, take on different roles, which emerge as various other values. And so melodic, rhythmic, or dynamic structures will bring out the values of the same note: pitch, duration, or nuance. Conversely, at its own level, the same object can be seen as carrying several different structures. As structures of duration, it will be broken down into slices of time, and attention will be given selectively, depending on its movement through time, to either its dynamic or its melodic criteria. As a whole, in its duration, memorized in time or perceived at a given moment, we could just as well consider this object a harmonic structure and endeavor to identify criteria, this time vertical and no longer to do with form in duration.

It can be seen that we still have to return to the synthesis of the object. Each of the earlier procedures in reality cancelled out the object on the level under consideration, in favor of a structuring process on both levels. But the object is all this; it is the sum of all these properties. It possesses all these characteristics. Any further, and we should forget its existence, its coherence, and think only about its functions. It does not have to be either in or out of a structure. We can isolate, contemplate, penetrate it. All this, explored, worked on by analysis, can be reassembled in an infinitely greater richness of perception, underpinned by our intention, if we wish. But do we?

21.11. MEANING AND SIGNIFICATION

Not always. And it is doubtless this that explains, more fundamentally than anything else, our two reservations regarding not only physicists but also linguists. We must once and for all determine the rules of the game between these two partners and the musician, who is a third.

The diagram in chapter 8, in fact, deals only with these three practitioners. One is concerned with the natural content of sound objects and, through the indicators it contains, seeks to control the event or demonstrate its workings. And this is where, as we have often pointed out, the scholar and the Native American are on the same side. The main thing is the focus on the event. The fact that it is natural—that is, common to man and animals, or referenced to meanings—6to more or less abstract systems is secondary, but it is understood that the focus is not on the object, that all that is retained from it is information about the event and not concepts, to which it would only be linked by virtue of convention. The linguist, in contrast, interested in sounds only insofar as they are signifiers conveying signified concepts, eliminates everything else from his study—that is, the properties of sound that have no function in this approach.

When we were dealing with music, we avoided using the term signification, too strongly suggestive of a code, or the purely arbitrary signified-signifier relationship, which, for sound, refers to the concept. Conversely, we can hardly deny that music has a meaning; that it is a communication between a composer and a listener, in spite of its essential difference from language (the sound no longer being the arbitrary medium of an idea, easily replaced by another); that a given music does not come, ultimately, from a system that, like a language system, is learned through two types of training, intellectual and auditory. It is this body of remarks that justifies us in saying that it is a language. Similarly, when we allow ourselves to talk about a “sign,” we mean all the values or pertinent features that underpin the function of a particular sound object in a musical structure, leaving aside its other nonpertinent properties.

To try to find this meaning in an abstract relationship analogous to the linguistic sign is to deny the evidence. At the very least, part of the musical lexis and musical syntax are inscribed in nature. We will try to rediscover their origins in four axioms.

21.12. CONSTITUENT ACTIVITIES: THE FOUR AXIOMS OF MUSIC

At the beginning of chapter 16 we mentioned two perpendicular structural chains. Until then, the horizontal object-structure chain seemed a foregone conclusion. Indeed. It functions from the very beginning in accordance with preconceived ideas, with a given material. If I listen to a singer, I know that, on the one hand, I am listening to a speech chain, which follows a verbal material, a code, and so forth, and with an intention to understand a language system; on the other hand, I also know (and can easily identify this if the singer hums without words) that I must operate in a quite different fashion, in accordance with a musical material and code, and with an intention to hear music.

The same “sound phenomenon” (for the singer has split into a speaking and humming singer only to convince us of this) can thus be broken down in different ways, depending on different constituent intentions.

We should not therefore be surprised that it is not enough to put ourselves in the presence of collections of putatively musical sound objects for something to happen. We must, here as well, examine the perpendicular chain and discover a founding mechanism of the musical.

The very great difference, then, between the conventional and the experimental approach is that the former can still seek inspiration in the linguistic approach, starting from a given material, in some way a scientific object, whereas the other starts from the other direction, backward, as we have already said. This, moreover, explains why, with the same numbers and in boxes as close together as the square and the diamond in our illustration, the contents are so profoundly different, perhaps more than we should like to admit on first reading.

The traditional situation is a de facto situation, and it does not much matter whether the facts are natural or cultural. They have developed so slowly, they have matured for so long, they have become so full of meaning, that we cannot but benefit from their being reorganized, even if these reorganizations seem at first sight artificial. For it is art we are dealing with, and in a moment we will prove that we have to return to this as the ultimate research objective. For instruments are given, registers are given, as are all manner of relationships between values (melodies, harmonies, rhythms), and also characteristics, since man first came into being and worked at his instruments. We can tear up all these collections of sounds grouped in this way, restructure or unstructure them. Let us take a pickaxe to this system: we are bound to find meaning in it; it contains a hidden treasure.

If we do indeed overthrow the lot, compare object with object, in the totally disparate mass of sound and the most uncertain intuition about the musical, how can we imagine this enterprise without formulating working hypotheses, without becoming aware of a choice of musical axioms that are tantamount to new constituent activities?

This is the main raison d’être for the four major relationships that appear in the four sections of the diamond.

It is indeed a matter of choosing four axioms for the musical. These choices are as follows. The articulation-stress pair underpins the choice of types. The form-matter pair determines sound morphology. The criterion-dimension pair is the one that ultimately gives a meaning to the analysis of objects: the meaning of its musical proportions.

This leaves the choice for the last section, where we find the well-known pair value-characteristic and a variant of it, which we will not deal with until book 6: variation-texture.

21.13. SYNTHESIS OF MUSICAL STRUCTURES OR THE INVENTION OF MUSICS

Whereas in the conventional system every structure was given (and, in theory, full of meaning owing to the suitability of the objects), in this one we start from the various structures of sound, which are immediately broken up and artificially restructured in accordance with the rules for identification and typological classification in sector 2. So we compare these objects in order to bring out the perceptual criteria suitable for the musical. There is nothing that is not classical about these two successive analyses, each time leaving the higher-level object in order to concentrate on the lower-level elements. So in sections 2 and 3 of figure 24 we have covered three levels, which from now on we will call sound structures, sound objects, and sound criteria.

Everything changes meaning and becomes expedience, artificial in the higher sections. Unlike a scientific or linguistic investigation, starting from natural or cultural facts, we intend to go the other way—to put sound objects into a structure and see what this gives. We must not forget, in fact, that every structuralist approach applies to preexisting structures, already given, for example, in languages. Thus the object-structure chain, like our grandmothers’ knitting, unravels in one direction. It is impossible to knit it up again so easily, by going from preexisting objects to automatic structures. Thus the chemist is never sure of achieving a synthesis, which cannot be safely deduced from analyses.

So we try out groups of objects; we feel our way instinctively, until the collection begins to say something to us. This shows we are approaching, or can hope for, an authentic structure, that is, one that is perceived in reality, where, precisely, these objects could be exploited as a value. So the principle behind sectors 4 and 1 can be seen much more clearly from this new (and adventurous) perspective. In 4, we form collections of objects in which we identify a certain sound criterion, and we see whether these objects, in spite of the disparity of their other criteria, will reveal relationships within the criterion under consideration that are meaningful, that is, can be described, ordered, or located in our musical perceptual field. Then we know we are working in the worst of conditions. Our morphological experiment has indeed revealed this criterion (as was the case with pitch in our experiments in section 21.8); but at best, all we have is (various) pitches given by (various) timbres. We know this experiment was already less convincing for the most robust value in music. How fragile will be those in which, in the disparate mass of characteristics, we endeavor to postulate the structures of an unknown criterion, necessarily less secure than pitch. . . . This is musical invention.

Now we can grasp the complementary need for the musicianly invention in sector 1. We need to go back to collections of the third type, analogous to piano or violin notes leading to registers. Registers such as these, while having all sorts of equally variable criteria in terms of pitch, did not disturb that perception and sometimes reinforced it. Is this possible? We could say yes, technically. We might refuse to give such a prompt reply in respect of artistic value, that is, the potential development of musics based on fundamental relationships such as these. We have already demonstrated this mechanism with the Klangfarbenmelodie. By fixing a value for pitch, it is possible to make a structure of timbres, provided we remove any allusion to instruments. We know how to do this better than our predecessors, without, for all that, maintaining that it is a very joyous finding for music. We will go further. We will imagine sounds with a less salient pitch (e.g., nonharmonic sounds). A register of sounds like this, where the characteristic of pitch does not dominate, will offer the potential for another structure, color, or thickness, provided we are not concerned with a suitable harmonization of the characteristic shared by the objects in the collection. Now we imagine a series of melodic glissandi or dynamic grains. These are criteria that could become dominant characteristics. They are not necessarily desired by the ear: but such glissandi, such grains, demonstrate the possibility of structuring objects that have a strong, inherent characteristic between which value-relationships can then be established.

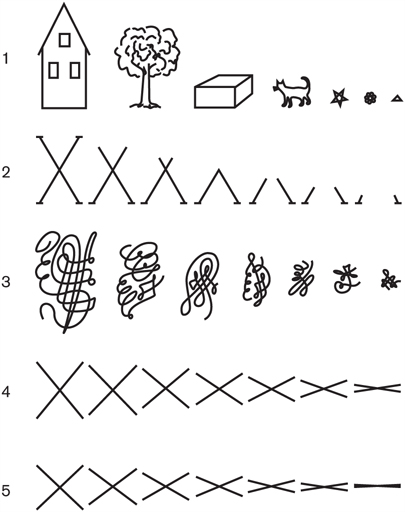

We thought of illustrating these ideas in figure 25. The first line shows a collection of completely disparate objects. It is only because of the artificial arrangement on paper or the comparison with other lines that we are tempted to arrange them in order of “height.”

FIGURE 25. Objects and structures.

The second line shows the opposite extreme. A single object is cut into slices. This is the physicist’s approach, taking no account of the form of the object and taking it to pieces from the top down, all other things being equal.

Line 3 introduces the neutrality of graphics; these objects, although formless, can nevertheless be arranged better in order of height.

Then there are two examples of a structure that is successful because of the permanence of its characteristics. In the last, there is reinforcement through concomitant variation in another dimension. In the penultimate figure, one dimension remains fixed, but the object retains its character. We must think back to the piano. We will represent the pitch of the note by the height of the X in our illustration and the brightness of its timbre by the width of its base. In a total transposition of a piano note, its specific timbre remained fixed, and only the pitch changed: this is what happens in the fourth line. In the case of the real piano the timbre becomes more bulky (the figure becomes wider) as the note becomes deeper (the height decreases): there is reinforcement and an equilibrium of proportion, visible here in plastic terms.

21.14. PROPERTIES OF THE PERCEPTUAL MUSICAL FIELD

We can see that, ultimately, the study of musical objects leads to the study of the properties of musical sensibility. We might have suspected this. In a situation not lacking in humor, and to which we have already drawn attention, it is scientists who would happily study our (musical) sensibility, whereas composers, true workaholics, would only delight in arranging “structured” objects, as they say, without the slightest regard for our perceptual properties or for psychoacoustic curves. Without doubt, the criterion and the perceptual field make up that relationship of indeterminacy that so upsets our usual vocabulary. For us to retain a sound criterion, it must also, on the one hand, be suitable and have musical interest and, on the other hand, allow for evaluation in our sensibility, with everything depending constantly on the objects presented and their own contexture.

We will also have to disconnect what musical habit has taught us to link together so strongly, because of the triple reinforcement of the value pitch, dominant first as a characteristic, then also as an ordinal relationship, then finally exceptional for its cardinal evaluation and its “vectorial” tensions, the only value out of all his perceptions that is given like this naturally to man.

In other words, an initial faculty of the perceptual field is the capacity to compare two objects, finding the same property in them. A second is the ability to order these values. A third is the ability to establish, more or less precisely, degrees for this calibration. Thus, we can equate colors with great precision but without being able to serialize them, and even less, find relationships of octaves or fifths between them, and with good reason.

21.15. CONTENTS OF THE EXPERIMENTAL SYSTEM

It sums up everything we have just said and ultimately does nothing other than apply the rules of structuring four times over. We will look anew at this description of the experimental system without deducing it, this time, from the conventional system. In this way we will come back to the findings in section 21.6, previously deduced by extrapolation.

(a) In the experimental system, then, we do not at first know what a timbre, or even a value, is. We start from sound chains. We cut these chains into pieces using the identification criteria “articulations and stresses.” And how will we sort these objects? By using the sustainment-intonation pair; we call this process typology. Identifying sound objects in this way, classifying and referring to them by a nomenclature of types, sums up the procedures in the new sector 2, the first sector of the experimental system.

(b) These objects, once identified, have contextures. To compare them is both to describe them (insofar as they are sound objects) and to identify the elementary perceptions to which they give rise. This is the morphology sector, which, in describing sound objects, will identify the perceptual criteria. How will we discover these? By analyzing the contextures using the fundamental form-matter relationship (which will be discussed in the next chapter, the first of book 5).

This concludes the analysis of sound decoded through what we have called a “musicianly” approach.

(c) But the comparison of sound objects has not yet involved the musical ear, in which, in theory, we expect to find a field of qualitative, even graded, appreciation. We are not going to claim to have rediscovered this entirely. We have practiced in it for a long time and are readying ourselves to refine or develop this field rather than limit it to what convention would give it to hear.

How are collections of objects, brought together to test out a particular criterion, structured in the natural field of the ear, refined, of course, by expert training? Here we find, by force of circumstance, the relationship of indeterminacy between the criterion presented to the ear and the perceptual field the ear can offer. We must not be premature in discussing this particularly delicate aspect of experience, always in the balance between the natural and the cultural, between innate gifts and the sometimes surprising potential of training: it is dealt with in musical invention in sector 4.

This relationship between the site of the criterion (or its caliber) and the perceptual field (or the dimensions of its musical calibrations) is the subject of sector 4, absolutely “analytical,” more to do with the senses than the sensibility, more scientific than musical, at least more experimental than artistic.

How can we draw practical conclusions for music from all this? How will we attain a generalized but perceptible musical, without conventions that are more artificial and maybe more arbitrary than the previous ones?

(d) We do so by renewing, through synthesis, the fundamental relationships between possible musical structures and by identifying objects, now justifiably described as musical, which are also, of course, made up of “bundles of criteria” (character) that, when put together, can, through the permanence of their criteria, produce an easily perceptible structure of values and have musical interest.

That is just about all for this chapter, which from all the traditional and experimental systems has compared only one state of musical structures: the discontinuous state, where the objects are distinct from each other. But what if the musical structure is continuous, because the objects are variants and ultimately linked? This subject will be discussed in chapter 33. It adds to the earlier relationship that governs the discontinuous in music a complementary relationship that links variation to texture, a law of the continuous in music. Our illustration of musical syntheses would be incomplete without this addition, to which we will return at the end of this work.

These are the aims of sector 1, now final, the aims of musicianly, here as much as musical, invention in the experimental system.