25

Typology of Musical Objects (II)

Balanced and Redundant Objects

25.1. BALANCED OBJECTS

It is likely that the most suitable sound objects for the musical will be those that conform to the criteria set out in the nine central boxes in figure 30, numbered:

23, 24, 25

33, 34, 35

43, 44, 45

These objects have in common that they have a good form; that is, they are held together by an undeniable unity of facture, with an optimal time for memorization by the ear, with the exception of the middle column (brief objects right down to the micro-object).

As for masses, these are what the orchestra takes as its usual material: fixed percussion masses, determined pitches of sounds notatable on the staff, or again sliding glissandi on the strings, the drums, and so forth.

So here we come back to describing balanced objects according to the two criteria of mass and facture, at greater length than in the preceding chapter, the purpose of which was simply to give an overall methodological view.

25.2. ANALYSIS BASED ON THE CRITERION OF FACTURE

With the aim of clarifying our perception of factures we will first of all adopt a mechanic’s approach, pointing out that it is possible to identify three characteristic ways of sustaining the vibration of a sound body: none at all (percussion), continuously (active sustainment), and repeated percussions (iterations).

Although traditional music, centered on pitch, has neglected this important and easily perceptible aspect of the sound object in formulating a theory, we can nevertheless pick up a distinction rather similar to our own in the form of performance directions, mainly for stringed instruments but also for woodwinds and even the piano:

— |

• |

“pizz.” |

“stac.” |

“trem.” |

(held sound) |

(plucked sound) |

(pizzicato) |

(staccato) |

(tremolo) |

This notation really relates to sustainment, since with varying degrees of imperiousness it lays down a way of making sound, with a view to its effects. But the notation also indicates considerations that are not exclusively to do with energy. A system of classification by sustainment alone would not be enough to link together or efficiently separate out the types of objects we meet all the time in traditional music alone: a brief violin sound (arco) is in fact sustained, whereas a bass piano note is not, but it is clear that the difference in sustainment, although perceptible, is not the only thing that characterizes the differences between the perceived factures. So, using what is suggested by traditional directions, but taking into account the sustainment criterion given above, we will have to define original facture criteria more fully.

In some cases the gesture will be perceptible; the form given to the sound will depend on the movement of the forearm or the breath; it will respond to a living dynamic: there will be a crescendo and a diminuendo that will shape the note, even if they are scarcely perceptible. The facture may disappear through excess or insufficiency: through excess if it is prolonged, through insufficiency if it does not have the time to make itself heard. If sustainment is prolonged, the sound will no longer be perceived as a measured form; only the mode of sustainment will be perceptible in its regularity or its fluctuations. On the contrary, in brief “plucked” sounds the only thing perceptible will be an all-or-nothing impulse. Of course, we will come across hybrids: a staccato, well executed from one end of the bow to the other, is as well formed an object as a bowed note “on the string”: the individual form of each impulse disappears into the general form. Finally, we should observe that our criterion of facture, linked with sustainment, will also bring into play the listener’s capacities for memorization.

By bringing these various elements together, we get the following main types of facture, which, for the sake of simplicity, we will apply here to musical notes that are common but can easily be generalized. First of all, the note with no particular sign: N will be a well-formed sound, situated between the sustained sound N̄ and brief sounds; among the latter we must distinguish between brief but sustained sounds, which we will notate N′ (e.g., a plucked violin note), and those that are similar to the pizzicato (i.e., a brief nonsustained sound), which we will notate Ṅ. (Here we must point out that in choosing these, we are deliberately diverging from the traditional practice of notation, in which Ṅ, and not N′, most clearly refers to a plucked violin sound.)

Furthermore, whether the sound is tonic or complex, we will generally keep the prime sign (′) for brief sustained sounds and the full stop (.) for percussion sounds. But then we must distinguish between a woodblock and a piano percussion sound, given the great morphological difference between the two corresponding sound objects. We will use the fermata for the piano to signify that the resonance of the note  follows the percussion (.) while the use of (.) alone will indicate the contrary (the absence of any resonance); this is the sign for the impulse or the micro-object.

follows the percussion (.) while the use of (.) alone will indicate the contrary (the absence of any resonance); this is the sign for the impulse or the micro-object.

Finally, we will use the double-prime sign (″) for iterative notes—that is, those formed of repeated brief sounds, staccato or drum roll, for example. As brief sounds, as we have seen, may be of type Ṅ or N′, we will have two types of formed iterative notes: (N′)″ and (Ṅ)″, that is, the bowed staccato and the drumroll on a sound body without resonance.

So eventually we have the following series for noniterative notes, ordered approximately according to the duration of the note’s continuation (whether this results from resonance or active sustainment):

and for iterative notes two pairs of variants of N and respectively

But such distinctions, which we will necessarily return to when we embark on an analysis of values and characteristics in book 6, are too refined for the stage we have reached at present. For the moment we will leave out prolonged sounds and consider only well-formed, sustained, or iterative notes—that is, N and N″: it will be simpler to place only one brief type between these two; we will not go into detail about sustainment. Therefore, ignoring the distinction between N′ and Ṅ, we will notate all brief sounds N′ and call them “impulses.” For the sake of similar simplification, the two types of iteratives (N′)″ and (Ṅ)″ arising from the previous ones will all be notated N″. Furthermore, we can bring the piano and the bow together if we take into account that both have a characteristic, profiled, memorable form; the nature of their sustainment thus taking second place, we will conflate  with N.

with N.

Ultimately we will retain only three central types: held sounds or formed resonances, impulses, and formed iterations, notated respectively: N, N′, and N″.

25.3. ANALYSIS BASED ON THE CRITERION OF MASS

Either one or the other:

• either the mass of the sound is heard as condensed into one point of the tessitura—that is, it has a pitch that meets the traditional definition of the musical note—and we notate it N; or, without being able to be clearly located, the mass appears fixed in the tessitura (even if, as with the gong or the cymbal, it displays large variations in timbre), and then we have a fixed complex note, which we will indicate with an X;

• or the mass of the sound evolves in the tessitura in the course of its duration. We find few examples of objects like this in the sounds of the traditional orchestra; the Hawaiian guitar is the most obvious in the variety orchestra; but modern music makes very great use of glissandi produced in all sorts of ways.

Moreover, most natural sounds, perhaps because of the various causes that give rise to them, have masses that evolve in the tessitura. All notes like this, described as reasonably varied, will be indicated with a Y.

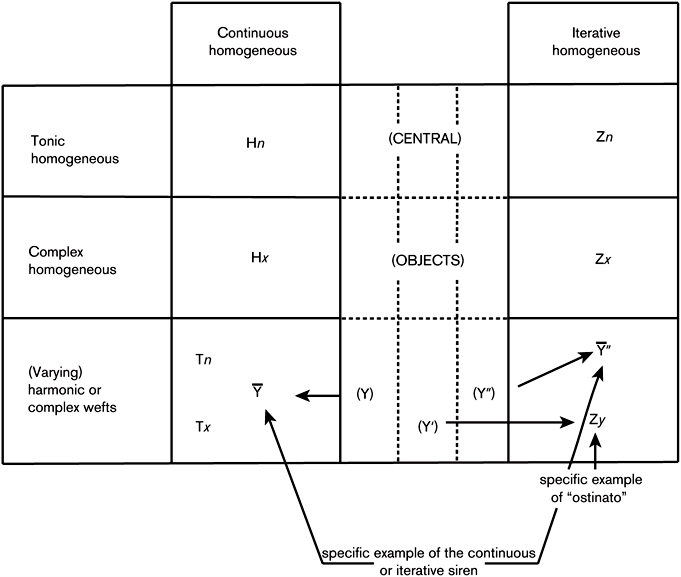

By combining the criteria of facture and mass, we finally obtain a figure with nine boxes of so-called balanced objects (see fig. 31).

FIGURE 31. Typology of balanced objects.

We will now endeavor to classify a few simple sounds according to this figure. We have already given examples for the first line. Going on to the second, we can only name a very few traditional musical objects that in theory come under the notation X, although low organ, piano, bassoon, and double-bass sounds are, in fact, heard as complex notes just as much as, and even more than, tonic notes. Conversely, experimental instruments, electronic or concrete (among the latter we could mention rods or sheet metal played with a bow) produce a great range of X as well as Y sounds.

A cymbal with a metallic brush drawn across it will give us an example of X. The same cymbal, struck and immediately muted, will give an X′ and, with a tremolo from ordinary or bass drumsticks, X″ sounds. A very slurred tremolo where the pulsations are indistinct will go back to being an X. The same is true of the drum. So we may have to go from one box to another: depending on how much we concentrate on sustainment, the context created by other objects and the conditions under which they are used, we will need to emphasize different typological characteristics. A system of classification based on perception offers precisely the advantage of highlighting and justifying this sort of flexibility, in keeping with the context and the intention of hearing objects at different levels of complexity or according to different criteria.

We will use Y to notate every glissando that in our judgment should be highlighted, and not just the most obvious, such as glissandi on the Hawaiian guitar; if, however, singers use these discreetly in order to ensure their voices are accurately placed, we can still use Y to notate what is clearly included in a well-defined N. Asiatic music, on the contrary, deliberately seeks out these Y or Y′ sounds, which bowed or wind instruments play slowly between two degrees on the scale, or strings and membranes produce when, violently plucked or struck, they begin to vibrate at a higher pitch than their final resonance. Finally, the slide-drum, dear to our avant-garde composers for its tremolo-glissando, gives us a surfeit of Y″ sounds.

25.4. REDUNDANT OR NOT VERY ORIGINAL OBJECTS

Going back to figure 30, we can see that we have not shunned the lack of originality or the redundancy of objects with either fixed or slightly varying mass: so it is facture that appears as the first criterion of redundancy in our discussion. To obtain redundant sounds, all we need to do is start from balanced objects as described in the last section and extend their duration until all dynamic form disappears. As above, we will have two types:

(a) Fixed mass:

The balance of an N or an X (or an N″ or an X″) will be upset through lack of originality when sustainment is prolonged indefinitely, whether a mechanical device creates the continuity or whether the instrumentalist deliberately intends this extension in time and absence of salience. In the latter case, where slight dynamic variations can still clearly be identified, we will have the sustained notes N̄ or X̄, or the unformed iterations (prolonged beyond the duration threshold of the ear)  or

or  . If the sustainment is mechanical, we can indicate the higher degree of regularity by using another sign to indicate homogeneity: the corresponding “homogeneous” sounds would be Hn, Hx, and the impeccable iterations Zn and Zx. However, as the transition between an Hn and an N̄ may be imperceptible, our use of two notations does not justify using two different boxes.

. If the sustainment is mechanical, we can indicate the higher degree of regularity by using another sign to indicate homogeneity: the corresponding “homogeneous” sounds would be Hn, Hx, and the impeccable iterations Zn and Zx. However, as the transition between an Hn and an N̄ may be imperceptible, our use of two notations does not justify using two different boxes.

Finally we should note that in general the redundant prolonged sounds Hn and Hx, Zn and Zx are of no interest when they occur in isolation; the more or less homogeneous sounds used in practice by the experimental musician are wefts T, harmonic packages or complexes of elementary N or X sounds put into “sheaves,” which we will discuss later.

(b) Variable mass:

How can we reconcile the idea of a redundant object with the idea of variation? In other words, how can a varied note such as a Y become redundant? Because when it spreads out in time, the variation, which is reasonable at the level of Y sounds, becomes, if not entirely predictable, at least unsurprising. So it is a question of relative redundancy.

We will begin with sounds with continuous sustainment. When it is formed and limited in time, note Y contrasts very clearly with notes N or X, and we can easily distinguish a melodic (Yn) or a complex (Yx) glissando. As soon as note Y distends, this latter difference, at least as far as sounds that hold the experimenter’s attention are concerned, will diminish. The prototype of Ȳ is of little interest: it is the slow siren, both varying and redundant, more obtrusive than a homogeneous sound but wearisome in the monotony of the variation itself. Musically, the most interesting types are less ordinary either because they show slow variations of melodic-harmonic structures, interweaving held N notes, or because they have complex X timbres superimposed in a variable or slowly evolving manner. The word note in varied note no longer applies here for superimpositions of such rich sounds, heard nevertheless as groups, for they are not made to be constantly analyzed and can thus meet the concept of object. These fusions of slowly evolving sounds are called wefts in our vocabulary, and they will be notated Tn or Tx, depending on whether their structure is formed mainly of N or X sounds.

What will happen with iterative Y sounds? There are two very distinct types here, the first being less engaging than the second: it is still the siren, going on endlessly, but this time staccato. Beside this irritating specimen, which could still be notated  if need be, we have the lively varied note Y′ constantly reiterated, like the interminable tweet-tweet of a bird or the regular creaking of a mill wheel. We are dealing with a sustained iterative of Y, which will be notated Zy. We are also happy to call this sound an “ostinato,” by analogy with this type of piano or orchestral accompaniment. We will soon find ostinati in the same column, but for the reiteration of more complicated objects than Y or Y′ sounds, and should prefer to reserve the letter P for this purpose and keep the notation Zy here for this particular example.

if need be, we have the lively varied note Y′ constantly reiterated, like the interminable tweet-tweet of a bird or the regular creaking of a mill wheel. We are dealing with a sustained iterative of Y, which will be notated Zy. We are also happy to call this sound an “ostinato,” by analogy with this type of piano or orchestral accompaniment. We will soon find ostinati in the same column, but for the reiteration of more complicated objects than Y or Y′ sounds, and should prefer to reserve the letter P for this purpose and keep the notation Zy here for this particular example.

25.5. PURE SOUNDS

If, in the great final diagram in the previous chapter (fig. 30), we assigned the first line to pure sounds, it was in the interests of symmetry, in order to contrast this line 1 with an eventual line 5 and thus keep a center to our classification. Besides, as we have seen, this symmetry is more to do with the layout of the schema than its contents: the simplicity of the objects in the upper half does not in fact really balance with the huge diversity of those in the lower half. Moreover, differentiating between defined sounds with a recognizable instrumental timbre and electronically pure (sine wave) sounds, even assuming this were possible in every case, actually depends on a fine distinction that the general typology of sound objects could not accommodate. We therefore propose purely and simply to get rid of the first line as superfluous. It is true that sounds with weak facture will be more redundant there than elsewhere, stripped of any harmonic fluctuation, developing in a completely straight line. Since we locate these sounds in pitch, it will do to put them in the second line, which then becomes the first in the definitive figure.

25.6. SUMMARY DIAGRAM OF REDUNDANT OR NOT VERY ORIGINAL SOUNDS

FIGURE 32