SEVEN

New Guys with New Ideas

The British people of the North American Colonies are a people on whom we may safely rely, and to whom we must not grudge power. Lord Durham, in his report of 1839

By luck, Macdonald began his political career in 1844, at the best possible time for a newcomer to arrive at least in the wings of the political stage. Shortly before he got there, the Canadian political system had been decisively shaken up and had set off in an entirely new direction. Shortly afterwards, the system was galvanized by the introduction into it of a new, almost revolutionary, idea in governance. The decisive change was caused by a new constitution that joined the two previously separate colonies of Upper and Lower Canada (today, Ontario and Quebec) into the United Province of Canada; for the first time, the country’s two European peoples, French and English, were brought into direct political contact. The almost revolutionary idea was that of Responsible Government: it called for the colony’s government to be responsible to the elected legislature, not, as before, to the governor general. Under the old system, the governor general exercised unchallengable authority as the personal representative of the monarch; he selected and appointed all the ministers, who then functioned as his ministers rather than as those of the legislature and the voters. Transferring responsibility to elected ministers who commanded a majority in the legislature effectively ceded to the colony full self-government in domestic affairs. Only Confederation, still two decades away, would change the country as radically as these two measures.

For the politicians, whether Macdonald or anyone else, the effect was like that of a comprehensive spring cleaning. As Creighton observed in The Young Politician, almost all the leading political figures of the era before Responsible Government “failed, with astonishing uniformity, to survive very long in the new political atmosphere.” Macdonald thus joined the system at the very moment when it was time for new guys with new ideas. Except that Macdonald did not—yet—have any new ideas. He survived, nevertheless, because he was street-smart and a quick learner. Still, he contributed nothing to the transformational changes themselves, and it took him time to figure out how to take advantage of the extra space at the top that had just been opened up for someone like him.

Macdonald also had to cope with practical constraints. During his first term, from 1844 to 1848, he was a backbencher, literally as well as figuratively, because he chose to sit in the very back row. His appearances on the actual stage itself were in the junior cabinet posts of receiver general and commissioner of Crown lands, in each instance briefly. During his second term, from 1848 to 1852, he sat in opposition, because the Conservative government had lost to the Reform Party. Mostly what he did during this time was to listen and learn, to make useful contacts and to acquire insider know-how, all of which would be highly useful, whether he chose to give politics up for the law or try clambering up the ladder.

As an even more practical constraint, Macdonald was having problems with his law practice. Campbell complained, justifiably, that he was being underpaid, particularly because Macdonald was often absent on political business. In 1846 they rewrote their original agreement, this time dividing the general profits equally between them, giving Campbell a third of the Commercial Bank business and allowing him a lump payment of £250 a year to compensate for Macdonald’s absences. This arrangement tightened Macdonald’s finances at the very time he had to look after a permanently invalided wife as well as his mother, who kept suffering strokes even while recovering from the latest, and provide for the financial needs of his unmarried sisters, Margaret and Louisa.

Before we carry on with the chronicle of Macdonald’s career, it’s necessary—anyway, it ought to be useful—to describe the new political environment within which Macdonald now found himself operating.

Here, all readers to whom this mid-nineteenth-century period of Canadian politics is a well-annotated book should jump ahead to the next chapter. However, their ranks may be relatively thin. A great many Canadians have come to assume that their country began on July 1, 1867, not least because we celebrate each year that anniversary of Confederation. But Confederation wasn’t the starting point of all that we now have and are. It developed from its own past, and that past, even if now far distant from us, still materially affects our present and our future.

The most explicit description of the continuity of Canadian politics across the centuries is made by historian Gordon Stewart in his book The Origins of Canadian Politics. There he writes, “The key to understanding the main features of Canadian national political culture after 1867 lies in the political world of Upper and Lower Canada between the 1790s and the 1860s.”*32 His argument, one shared fully by this author, is that all Canadian politics, even those in our own postmodern, high-tech, twenty-first-century present, have been influenced substantively by events and attitudes in the horse-and-buggy Canada of our dim past.

One key example would be the role of political patronage in Canadian politics. Except on rare occasions, our two mainstream parties have either no ideology at all or only fragments of it. Their distinguishing difference is not in their titles, Liberal and Conservative, but in the fact that, at any one time, one party is in and the other is out. Without patronage, it would be just about impossible for either organization to function as a national party. Other motives, of course, attract individuals to join one or other of the mainstream parties, which alternate, rather irregularly, in office: idealism, the attraction of public service and, no less, the adrenaline high that is generated by the fierce competitiveness of the political game. But the prospect of good, high-status jobs matters as critically—in effect, no patronage, no national political parties. (Regional parties have in their very regionalism a substitute for ideology, as do the rarer ideology-driven parties like the New Democrats and the Greens.) Two international comparisons may confirm the point: in Britain, from which we originally copied a great deal, there is relatively little patronage but a considerable difference in ideology between Labour and Conservative; in the United States, always our principal comparison, there is about as much patronage as there is north of the border, but Democrats and Republicans differ in their ideology or, perhaps more particularly these days, in their cultural assumptions. Patronage really is as Canadian as maple syrup.

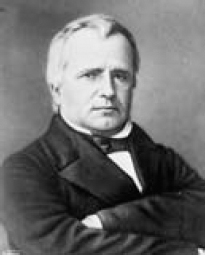

Lord Durham, known as “Radical Jack.” He found “two nations warring in the bosom of a single state” and set out to assimilate the second one—les Canadiens.

Another example, this one unique to Canada, is the effect on our political system of the ongoing alliance of convenience between the French and the English, or now, more accurately, of francophones and English-speaking Canadians. No less so before Confederation than after it, whichever party has been able to forge a partnership with francophone Quebecers has almost automatically become the government and remained in power for a long time. Few of Macdonald’s political insights were as perceptive as his recognition early on that a stable national government would be impossible without abundant amounts of patronage and a close, mutually self-interested apportionment of the spoils (including that generated by government spending) between the French and the English.

Now to go back to our future, this of course being also Macdonald’s present.

The catalyst of fundamental change in pre-Confederation politics were the rebellions in 1837–38 by the Patriotes in Lower Canada led by Louis-Joseph Papineau, which was a serious uprising, and by the rebels in Upper Canada led by William Lyon Mackenzie, which was more of a tragicomedy. Both uprisings provided a warning to London that, as had gone the American colonies a half-century earlier, so the colonies of British North America might also go. To deal with the crisis, the Imperial government sent out one of its best and brightest.

John George Lambton, Earl of Durham, arrived accompanied by an orchestra, several race horses, a full complement of silver and a cluster of brainy aides, one of whom had achieved celebrity status by running off with a teenage heiress and serving time briefly in jail. Still in his early forties, “Radical Jack” was cerebral, cold, acerbic and arrogant. After just five months in the colony, he left in a rage after a decision of his—to exile many of the Patriotes to Bermuda without the bother of a trial—was countermanded by the Colonial Office. Back home, he completed, in 1839, a report that was perhaps the single most important public document in all Canadian history.*33 Lord Durham himself died of tuberculosis a year later.

Parts of Durham’s report were brilliant; parts were brutal. The effects of each were identical: they both had an extraordinarily creative effect on Canada and Canadians. The brutal parts of Durham’s diagnosis are, as almost always happens, much the better known. He had found here, he declared, “two nations warring in the bosom of a single state…a struggle, not of principles, but of races.”†34 The French Canadians, les Canadiens, had to lose—for their own sake. They were “a people destitute of all that could constitute a nationality…brood[ing] in sullen silence over the memory of their fallen countrymen, of their burnt villages, of their ruined property, of their extinguished ascendancy.”

In fact, Durham was almost as harsh about the English in Canada. They were “hardly better off than the French for the means of education for their children.” They were almost as indolent: “On the American side, all is activity and hustle…. On the British side of the line, except for a few favoured spots, all seems waste and desolate.” He dismissed the powerful Family Compact as “these wretches.” Still, he took it for granted that Anglo-Saxons would dominate the French majority in their own Lower Canada. “The entire wholesale and a large portion of the retail trade of the Province, with the most profitable and flourishing farms, are now in the hands of this dominant minority.” All French Canadians could do was “look upon their rivals with alarm, with jealousy, and finally with hatred.”

The only way to end this perpetual clash between the “races,” Durham concluded, was for there to be just one race in Canada. The two separate, ethnically defined provinces of Upper Canada and Lower Canada should be combined into the United Province of Canada. As immigrants poured in from the British Isles, the French would inevitably become a minority. To quicken the pace of assimilation, the use of French should cease in the new, single legislature and government. To minimize the political weight of Lower Canada’s 650,000 people, compared with Upper Canada’s 450,000, each former province, now reduced to a “section,” should have an equal number of members in the new legislature.*35

Montreal. Place d’Armes, with a view of Notre Dame church, c. 1843. It was Canada’s only real city, the first to install such technology as gas lights and the horse-drawn omnibus.

Durham’s formula worked—but backwards. Quebec’s commitment to la survivance dates less from Wolfe’s victory over Montcalm (after which the Canadiens’ religion and system of law were protected by British decree) than from 1839, when Durham told French Canadians they were finished. The consequence of this collective death sentence was an incredible flowering of a national will to remain alive.*36

In the years immediately following 1839, a sociological miracle occurred in Lower Canada: a lost people found themselves. Historian François-Xavier Garneau, the poet Octave Crémazie, and Antoine Gérin-Lajoie, author of the patriotic lament Un Canadien Errant, created the beginnings of a national literature. Étienne Parent, a brilliant journalist, wrote a long series of articles calling for sweeping social, educational and religious reforms. The Instituts canadiens were founded as a means of generating intellectual inquiry and speculation and as a form of adult education. Montreal’s Bishop Ignace Bourget, an ultramontane,*37 or right-wing Catholic, attracted major orders of priests—the Jesuits and the Oblates—and four orders of nuns to staff the new collèges classiques, from which a new and educated middle class would soon graduate. In 1840 there was just one priest for every two thousand parishioners; by 1880 there was one for every five hundred. As historian Susan Mann Trofimenkoff wrote in The Dream of Nation, “the clergy was as much a means of national unity as the railroad.” The culmination of this new surge in national self-assertiveness, the Société St-Jean-Baptiste, was established in 1843.

Few in Upper Canada noticed. Their attention was focused on the other part of Durham’s report, one calling for a totally different kind of Parliament. It was to be a responsible Parliament, with a cabinet composed of members of the majority party rather than chosen at the pleasure of the governor general. In a phrase of almost breathtaking boldness, Durham wrote, “The British people of the North American Colonies are a people on whom we may safely rely, and to whom we must not grudge power.”

Durham almost went right to the constitutional finish line. He recognized the advantages of Confederation: “Such a union would…enable all the Provinces to cooperate for all common purposes,” he said. “If we wish to prevent the extension of this [American] influence, it can only be done by raising up for the North American colonist some nationality of his own.” At the last instant, Durham drew back from specifically recommending Confederation because he doubted that Canada possessed politicians of the calibre needed for so ambitious an undertaking.

At the time, Durham’s report attracted little applause either in Canada or in Britain. A century passed before it came to be recognized by some as “the greatest state document in British imperial history.” His recommendation for Responsible Government began a fundamental reordering of the Empire, and it set the political maturation of the British North American colonies in motion. Had that precedent—and its logical successor of Confederation—been applied to Ireland, as William Gladstone attempted in his Home Rule Bill in 1886, thousands of lives could have been saved.

Embedded in the proposal for Responsible Government was a fundamental illogicality. The colonial secretary, Lord John Russell, spotted it immediately: it would be “impossible,” he wrote his cabinet colleagues, “for a Governor to be responsible to his Sovereign and a local legislature both at the same time.” To stop Responsible Government, the British government sent out another of its best and brightest, Lord Sydenham, then in the cabinet as president of the Board of Trade. Still in his thirties, multi-lingual, highly professional and confident to the point of cockiness, Sydenham was one of the ablest of governors general—and one of the most dashing. Described as “worship[ping] equally at the Shrine of Venus and at the Shrine of Bacchus,” he died following a fall from his horse after a visit to his mistress. He was also one of the more corrupt. The election of 1841, which he ran single-handedly, has few equals in Canadian history for chicanery, gerrymandering, vote-rigging, bribery and the systematic use of violence. Sydenham’s candidates won handily.

To implement the part of Durham’s program that the British government found wholly acceptable—the assimilation of the French—Sydenham moved the seat of government to Kingston, its attraction being that it was entirely English-speaking. All the legislative documents were unilingual; and the Throne Speech, read by Sydenham himself, was in English only.*38 Following his death later that year, his successor, Sir Charles Bagot, quickly recognized that Britain had positioned itself on the wrong side of history. “Whether the doctrine of responsible government is openly acknowledged or only tacitly acquiesced in, virtually it exists,” Bagot wrote home in 1842.

In fact, Britain ceded Responsible Government with remarkable readiness. The quite separate colony of Nova Scotia actually gained it two months ahead of Canada, in 1848. But it had been allowed effectively in 1846, when Britain adopted free trade and abolished its protectionist Corn Laws and Navigation Laws. Thereafter, Canada and several other colonies were free to make their own trading arrangements, thereby exercising de facto self-government.

The fight for Responsible Government mattered, though. It entered Canadian political mythology as a sort of non-violent version of the Boston Tea Party. And the struggle brought together one of the most important and appealing of all Canadian political partnerships, one that would provide Macdonald with a template of the way to fashion and sustain a political alliance between the country’s two principal European races.

One of these partners was Robert Baldwin. The son of a successful lawyer, William Baldwin, who had originated the idea of Responsible Government, Robert came from the same social circles as the Family Compact. He was highly intelligent and of irreproachable integrity. Robert took over the cause from his father and, in January 1836, sent a letter to the Colonial Office. In it, he made a case for Responsible Government on the politically shrewd grounds that it was essential for “continuing the connection” with Britain. Durham’s advocacy of the idea can be dated to this letter.

The other partner in the emerging alliance was Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine. He was the prototype of the commanding le chef figure whom Quebecers have so often followed. Grave in manner and exuding gravitas, LaFontaine was blessed with a resemblance to Napoleon that he assiduously fostered. As a one-time Patriote, he had nationalist credentials that were unimpeachable.

Robert Baldwin. He won Responsible Government, or self-government, for the colony of Canada. High-minded and single-minded, he was known as the “Man of the One Idea.”

Soon after the formal creation of the United Province of Canada, LaFontaine spotted an opening for himself and for his Canadiens. Skilfully used, the new configuration could lead not merely to la survivance in defiance of Durham’s assimilation program but to substantive economic benefits for his people. He saw that an alliance between his bloc of French members and the Reform group led by Baldwin would form a majority in the legislature. Baldwin would get the Responsible Government he so desired (even if it was of small interest to LaFontaine, who, by inclination, was a conservative). In exchange, LaFontaine would get the keys to the patronage treasure chests that Responsible Government would transfer from the governor general to the Canadian politicians in power. Though a partnership of convenience, the alliance was also one of principle and of personal trust. In the election of 1841, with LaFontaine badly in need of a winnable seat, Baldwin found one for him among the burghers of the riding of Fourth York in Upper Canada. A year later, LaFontaine returned the compliment by handing to Baldwin the equally unilingual riding of Rimouski. (And at the personal level, Baldwin sent all four of his children to French schools in Quebec City.)

Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine. With Baldwin, he forged a French-English political alliance that turned Durham’s policy upside-down.

To move the Imperial government over to the “right” side of history took a new governor general, Lord Elgin. Exceptionally able, he was Durham’s son-in-law and, later, viceroy of India—the top position on the Imperial ladder.*39 The key year was 1848, when an election re turned a majority for Baldwin and LaFontaine. Acting on the principle of the sovereignty of the people, Elgin accepted the result and invited the pair to form the first biracial ministry. (Technically, LaFontaine, the leader of the largest bloc of members, was the premier. In practice, Baldwin functioned as co-premier, a system followed throughout the life of the United Province of Canada.) At the opening of that year’s session of the Legislative Assembly, Elgin read the Throne Speech in English, as all his predecessors had done, and then, after a fractional pause, read it again in French. Canadien members burst into wild applause and song; one so forgot himself that he rushed up and kissed the governor general on both cheeks.

Governor General Lord Elgin, with his wife, Mary Louisa, her sister and an aide. Unusually able and far-sighted, he ended Durham’s assimilationist policy by reading the Throne Speech in English and then, for the first time ever, repeating it in French.

The main immediate beneficiaries of the change were the graduates now pouring out of Lower Canada’s collèges classiques. Historian Jacques Monet has memorably described what happened in his essay “The Political Ideas of Baldwin and Lafontaine”: “With a kind of bacterial thoroughness it [Quebec’s emerging middle class] began to invade every vital organ of government and divide up among its members hundreds of posts.” Monet went on to remark that Canadiens “came to realize that parliamentary democracy could be more than a lovely ideal: it was also a profitable fact.”

Elgin accepted this downgrading, for himself and for his successors. In a dispatch to the colonial secretary he remarked that, henceforth, governors general would have to depend on “moral influence,” adding, surely without really believing it, that this could “go far to compensate for the loss of power consequent on the surrender of patronage.” Even Baldwin, himself skittish about patronage, declared stoutly in a legislature speech that “if appointments were not to be used for party purposes, let those who thought differently occupy the treasury benches.”*40

As always in government, some of the consequences of Responsible Government were unanticipated. The transfer of power from the governor general to elected politicians meant that Canadians hereafter placed blame for the mistakes that all governments make no longer at the entrance to their governor general’s residence but at the doors of their cabinet ministers and premiers. Certainly, the tone of Canadian politics worsened from this time on. Sectarianism, or the injection into politics of the rivalries, suspicions and hatreds between religious groups, now became the dominant issue in Canadian politics. No less significant, once the premiers occupied the shoes of the governors general, they began to acquire some of the quasi-dictatorial habits of those who had run the country before the change to Responsible Government in 1848. Cabinet ministers now became the premiers’ ministers, just as they had once been ministers of the Crown’s representative. The ascent to an imperial prime ministership—best described by Donald Savoie in his Governing from the Centre—began very early in this country’s history; it happened, moreover, far earlier here than in the United States, occurring there largely because the United States acquired immense foreign responsibilities—always quasi-imperial in their nature—which was not at all the case here. An imperial prime minister is another political attribute that is as Canadian as maple syrup.

These were epochal changes to Canada’s political makeup. Yet Macdonald’s contribution to them was almost non-existent. He made a few somewhat critical but carefully noncommittal comments about Responsible Government as a potential threat to the connection with Britain. For the most part, though, he simply listened and learned. It wasn’t long, now, before the era of Responsible Government would be replaced by the era of government by Macdonald.