THIRTEEN

Double Majority

Is it a decree of destiny that Mr. Macdonald shall be the everlasting Prime Minister? We must face issues.

The Colonist, June 19, 1858

As the decade of the 1850s drew to its end, Macdonald was approaching a political peak. He had outmanoeuvred Brown over the “double shuffle” with all the ease of a feral cat toying with a mouse. The bloc of bleu members who followed faithfully behind Cartier assured him of a semi-permanent majority in the legislature. His Liberal-Conservative Party, while shaky in several places, hugged the vital centre of the political spectrum, with the Tories in its ranks lapsing into sullen silence. As the de facto premier since 1854 and as co-premier in title since 1856, he’d held that post longer than had anyone in the life of the United Province of Canada. He’d deployed his tactics of compromise and accommodation to dispose successfully of long-standing issues such as the Clergy Reserves, the seigneurial system and separate schools, and had managed to select a single capital for the nation. Encomiums about Macdonald that floated across the Atlantic from the upper reaches of the Colonial Office described him as “a distinguished statesman” and “the principal man” in Canada. It’s always easier, though, to stumble when standing on a peak than on flat ground.

The warning to Macdonald came from an inconsequential source. On June 29, 1858, a small newspaper, the Colonist, ran a startling editorial titled, “Whither Are We Drifting?” After citing examples of national drift, it asked, “Is it a decree of destiny that Mr. Macdonald shall be the everlasting Prime Minister? We must face issues. Worse can happen than a ministerial defeat.” What was truly startling was the fact that the Colonist was a pro-Conservative newspaper—and that it was on to something. A disconnection had opened up between the governed and the governing; a disconnection, that is, between reality and politics.

Early in 1858, a letter proposing an extravagant idea crossed Macdonald’s desk. In it, Walter R. Jones of Kingston suggested that the government should encourage the formation of a company to build a railway “through British American territory to the Pacific.” The next step should be “a line of steamers from Vancouver Island to China, India, and Australia.” Although the historical record contains nothing more about Jones, his letter catches perfectly the spirit of the times.

The years from the late 1850s to the mid-1860s were either the best that Canadians experienced throughout the entire nineteenth century or a close second-best.*73 Everything was booming. The economy was benefiting triply: from the Reciprocity Treaty (a free trade deal) with the United States, a general upturn in world trade, and the special demands created in Britain by the Crimean War and the closing of the rival lumber trade from the Baltic. Immigration was booming, at the same time as outmigration to the United States had slowed substantially. Towns such as Toronto and Quebec were acquiring some of the characteristics of cities, while Montreal, with close to one hundred thousand inhabitants, was not that far behind Boston. Promising new manufacturing towns were taking shape, including Hamilton and Brantford; London, in just the last half decade of the fifties, tripled its population to fifteen thousand.

The word “progress” was on almost everyone’s lips. In The Shield of Achilles, edited by W.L. Morton, the historian Laurence S. Fall is notes that there was “an almost total absence of a literature of pessimism in the Province of Canada.” Optimism was generated by the abundance of jobs and by rising wages. By no coincidence, a great many of the country’s finest and boldest buildings, most spectacularly the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa, but also churches, cathedrals and public halls such as Toronto’s St. Lawrence Hall, date from this period. One other agent of change affecting Canada more decisively than any other country in the world was the steam engine, and the parallel lines of steel that stretched out beyond the horizon.

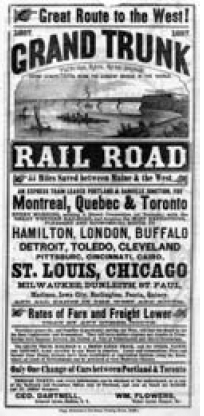

Initially, Canadians went timidly into the Age of Railways. In 1844, a decade and a half after George Stephenson’s famous Rocket made its first run in England, there were just fifty miles of track in the entire country. Then Canadians embraced the new age of transportation totally and extravagantly: by 1854 there were eight hundred miles of track; by 1864 there would be more than three thousand, including the Grand Trunk, reputedly the longest line in the world, stretching all the way from Quebec City to Sarnia. Soon, there were lines all over the place, built by the Great Western, the Northern Railway, and the St. Lawrence and Atlantic. In fact, almost all these companies lost money and had to be subsidized by government. Often the railways disappointed; their underpowered locomotives repeatedly broke down and could be halted by even minor snowdrifts.

Poster for the Grand Trunk Railway, the longest railway in the world. The illustration shows the tubular iron Victoria Bridge, which spanned the St. Lawrence River. It was completed in 1859 and, the next year, was opened officially by the visiting Prince of Wales. Both railway and bridge reflected the emerging expansionist and confident Canada.

Railways were by no means the only catalyst of change. Canada’s Pioneer Age was beginning to pass. The last parcel of “wild land” in the Bruce Peninsula was sold in 1854; the first “macadamized” roads were being built; and a few towns even boasted street lights. In some homes, parlour organs broadened the means of entertainment beyond fiddles and squeeze boxes. People had begun to realize that each new mechanical advance was not a fluke but the product of a system that would forever produce more and more marvels, from the mechanical harvester and the sewing machine to the telegraph. Many of these inventions brought further radical changes, such as the division of labour and the elimination of distance. During this period, no change would be more transformational than the publication in 1859 of a massive, near-unreadable tome—Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. Decades would pass before the melancholy, long withdrawing roar”*74 of the loss of faith would reach Canada, but a defensive response came early when the curriculum of the required courses at the University of Toronto was altered to incorporate natural theology and “evidences” of the validity of Christianity.

One Canadian sage compared the transformational effect of the railways to that of the invention of printing. They made a huge difference, although the small-engined locomotives had a hard time pushing through the snow on the Grand Trunk rails.

Nothing, though, changed Canada more than did the railways. In 1849 the Montreal engineer Thomas Coltrin Keefer, a kind of nineteenth-century Marshall McLuhan, published a pamphlet, Philosophy of Railroads, in which he proclaimed, “Steam has exerted an influence over matter which can only be compared with that which the discovery of Printing has exercised upon the mind.” A century later, the historian Michael Bliss revisited this idea in his book Northern Enterprise: “Steam conquered space and time. It seemed to liberate communities from the tyrannies of geography and climate…. Steam changed the land itself, for wherever the rails went, they gave the land value.” From now on, Canadians were less and less immured in their villages and small towns. They could reach out to each other to exchange everything from goods to ideas. Newspapers—the Toronto Globe most particularly—ceased to be purely local; business, from nail-makers to insurance companies, began to operate on a province-wide basis. Goods became more diverse and more competitive, and food became fresher and more varied. Mrs. Beeton’s monumental cookery book became available in 1860. Time became standardized—by Sandford Fleming. In short, Canadians began to become a single community.

This was the environment, optimistic and expansive and ever more agreeable, in which a great many Canadians lived during the last years of the 1850s and the first of the 1860s. Keefer proclaimed, “Ignorance and prejudice will flee before advancing prosperity.” The magazine Canadian Gem and Family Visitor told its readers: “Canada is destined to become one the finest countries on the face of the globe.” The geologist and surveyor of the west, Henry Youle Hind, in his book Eighty Years Progress of British North America predicted “a magnificent future…which shall place the province, with the days of many now living, on a level with Great Britain herself, in population, in wealth, and in power.” That the nineteenth century would belong to Canada seemed obvious; the politicians, though, were talking quite differently.

The changing circumstances did effect political change. Railways gave politicians a whole new range of power: they could decide who would win a charter to build and operate a company, and where its line should go. It could also give them personal profits—Premier MacNab as president of the Great Western; Cartier as solicitor for the Grand Trunk; and Hincks, the ex-premier, as a major shareholder in the same company. A British lobbyist for the Grand Trunk remarked, “Upon my word, I do not think that there is much to be said for Canadians over Turks when contracts, places, free tickets on railways or even cash was in question.” Put simply, there was now incomparably more money than ever before rattling around inside the Canadian political system. Keefer described the period as “the saturnalia of nearly all classes connected with railways.” Surprisingly, Macdonald himself never seems to have benefited personally from this first railway boom, and the only shares he appears to have bought were a modest number in the Great Southern Railway. But Canadian politics had undergone a sea change from its glory days of fighting for Responsible Government.

Macdonald ought to have been thoroughly enjoying himself. The boom made people happy, and happy voters are grateful voters. Yet time and again, Macdonald’s naturally sunny nature seemed clouded by an undertone of dissatisfaction—as if he himself was wondering, “Is that all there is?” The frustration came through in comments he wrote to friends: “I find the work and annoyance too-much for me,” and, “Entre nous, I think it not improbable that I will retire from the Govt.” He even let down his guard enough to allow some of his pessimism to creep into letters to his family. To his sister Margaret, he wrote, “We are having a hard fight in the House & will beat them in the votes, but it will, I think, end in my retiring as soon as I can with honour” and to his mother, “We are getting on very slowly in the House, and it is very tiresome.” In 1859 the rumour spread that Macdonald intended to retire. Joseph Pope wrote of Macdonald, “I believe, [he] had fully made up his mind to get out.” The entreaties of Conservatives eventually kept Macdonald at his post, but, as Pope wrote, “sorely against his wishes.”

Macdonald expressed much the same sentiments in public. At a formal dinner given for him in Kingston in November 1860, he lapsed into quite-out-of-character self-pity. “When I have looked back upon my public life,” he said, “I have often felt bitterly and keenly what a foolish man I was to enter into it at all (Cries of ‘No, no’)…. In this country, it is unfortunately true, that all men who enter the public service act foolishly in doing so. If a man desires peace and domestic happiness, he will find neither in performing the thankless task of a public officer.”

One factor exacerbating Macdonald’s pessimism was sheer loneliness. He lived in boarding houses, as, for example, jointly with a Mr. Salt on Toronto’s Bay Street. In 1861 he wrote to his sister Margaret about his new apartment-mate, an Allan McLean: “He is a very good fellow but rather ennuyant and I will be glad when he goes. I am now so much accustomed to live alone, that it frets me to have a person always in the same house with me.”

His natural optimism was rubbed down further by the progressive weakening of his beloved mother, Helen. She died on October 24, 1862. Alerted by Louisa, Macdonald was at her side through her last days. She too was buried in the family plot at Cataraqui Cemetery. Of his own family, only Margaret and Louisa remained; also Hugh John, but by now he had become a detached son. From this time on, Macdonald had less and less reason to go to Kingston, and, inevitably, he became increasingly distanced from his own childhood and youth.

While Macdonald was subject to occasional depressions, this general mood of listlessness and pessimism was alien to him. His usual philosophy of life is set out in a reply he wrote to a friend who had complained about financial problems. “Why man do you expect to go thro’ this world with trials or worries. You have been deceived it seems. As for present debts, treat them as Fakredden [sic] in Tancred treated his—He played with his debts, caressed them, toyed with them—What would I have done without those darling debts said he.” Macdonald then described his creed: “Take things pleasantly and when fortune empties her chamberpot on your head—Smile and say ‘We are going to have a summer shower.’”

Not until later did Macdonald—by now without any real confidante—reveal a major cause of his sense of alienation and purposelessness. The occasion—to cite it here requires slipping out of the straitjacket of chronology—was a dinner in Halifax in September 1864, right after the close of the first Confederation conference in Charlottetown. During his speech, Macdonald turned confessional in a way that was most unusual for him. “For twenty long years I have been dragging myself through the dreary wastes of Colonial politics,” he told his audience. “I thought there was no end, nothing worthy of ambition, but now I see something which is worthy of all I have suffered in the cause of my little country.” By that vivid phrase—“twenty long years…through the dreary wastes”—Macdonald was coming very close to saying that his entire career had been an exercise in pointlessness.

Macdonald loved power for its own sake, and he loved the political game for itself, so it would be far too sweeping to conclude that he meant literally what he was saying. But there is hard truth in that analysis. Macdonald had not come into politics with any grand goal or vision, and after two decades in politics, a good half-dozen of them at the top of the ladder, he had yet to accomplish much that would linger after he left. During this time he had missed out on several chances to make real money or to have a normal family life. Most particularly, Macdonald was failing in politics itself. Rather than the national harmony that should have resulted from his turning the Conservative Party into a centrist group, by forging a French-English alliance and by settling long-standing disputes, what had grown stronger over these same years was disharmony, division and sectarianism.

Religion was the “other” of these times. Almost every topic of public debate was dominated by and deformed by sectarianism. It was Canada’s equivalent to the division then rapidly taking hold in the United States between the slave-owning South and the anti-slavery North. The Orange Order, its membership constantly augmented by new Irish Protestant immigrants, was becoming ever more explicitly anti-Catholic, and the moderate Ogle Gowan was steadily losing ground to the hard-liner John Hillyard Cameron. At the same time, the Catholics in Lower Canada were becoming ever more ultramontane, or authoritarian. In Toronto, Bishop Armand-François Charbonnel declared that any Catholic who possessed the vote but failed to use it to elect candidates committed to expanding separate schools was guilty of a mortal sin. Differences in religion multiplied those of race, and the reverse equally.

In particular in Upper Canada, there was an ever-rising anger at the political power exercised in the national legislature by Lower Canada’s Canadiens, this in important part because of the very alliance that Macdonald had forged with Cartier and his bloc of bleus. As was rare, Macdonald’s political antennae failed to function. He dismissed Representation by Population as “too abstract a question [for the public] to be enthusiastic about.” Rather, and as always in politics, appearance mattered far more than fact, and the appearance here was that the minority—a defeated one, moreover—was now in charge.

The responses went far beyond mutterings in the various Orange Lodges. The Globe laid it out explicitly: “Our French rulers are not over particular, we are sorry to say, and we are powerless. Upper Canadian sentiment matters nothing even in purely Upper Canadian matters. We are slaves…. J.A. Macdonald may allow his friend to buy an office, he may even take a thousand pounds of plunder, if he likes; so long as he please Lower Canada, he may rule over us.” George Brown was even more intemperate: he railed in the Globe against “a deep scheme of Romish Priestcraft to colonize Upper Canada with Papists…a new scheme of the Roman hierarchy to unite the Irish Roman Catholics of the continent to a great league for the overthrow of our common [public] school system.”

Macdonald was by no means without sin himself. While he deplored sectarian strife with a vigour few other English-Canadian politicians matched, he also exploited it. In a letter to education reformer Egerton Ryerson, after mentioning a grant to the university that Ryerson favoured, Macdonald urged, “The Elections will come off in June, so no time to be lost in rousing the Wesleyan feeling in our favour.” He wrote to Sidney Smith, a Reformer he was trying to lure into his cabinet, “We must soothe the Orangemen by degrees but we cannot afford now to lose the Catholics.” It was in this letter to Smith that Macdonald laid down his often-quoted maxim of how to rule: “Politics is a game requiring great coolness and an utter abnegation of prejudice and personal feeling.”

Two solutions existed. One was Macdonald’s policy of compromise, endlessly and exhaustingly pursued by guile, skill, outright deviousness and a sizable portion of self-interest. He still had Gowan on his side, and he had bought off the bleus, a great many them right-wing ultramontanes, by patronage. Despite its patches and outright holes, the Liberal-Conservative Big Tent still stood.

A second solution existed. Known as the “double majority,” it amounted to a mechanical device for keeping Upper Canadians and Lower Canadians apart from each other politically. Up to a point, this system could work for regional matters, but national or province-wide measures became virtually impossible to put into effect. The solution merely papered over the problem, at the cost of making government paralysis all but inevitable and permanent.

Macdonald began by refusing to accept the double-majority rule. Gradually, he came to apply the rule he himself had spelled out in his legislature speech of 1854, of “yielding to the times” rather than engaging in “affected heroism or bravado”—and, also, of saving his political skin. He now proclaimed, “In matters affecting Upper Canada solely, members from that section claimed the generally exercised right of exclusive legislation, while members from Lower Canada legislated in matters affecting only their own section.” This compromise ceded the double majority in fact, if not officially. It worked, but at the cost of making the legislature largely unworkable.

Paralysis was never absolute, of course. Work began in Ottawa in 1860 on the construction of a complex of Parliament Buildings of exceptional grandeur—and cost. In 1859 Macdonald’s finance minister, Alexander Tilloch Galt, enacted higher tariffs on British imports to preserve Canada’s vital Reciprocity Treaty with the United States. British manufacturers protested furiously, but the Colonial Office endorsed Galt’s schedule. Effectively, London thereby added full economic self-government to the political self-government already ceded to Canada. And the term “world class” began to be applicable to Canada. Besides the Grand Trunk as the world’s longest railway, the Victoria Bridge, spanning the St. Lawrence at Montreal and a marvel of tubular iron, was the world’s longest; completed in 1857, it was opened officially in 1860 by a visiting royal prince.

The Parliament Buildings under construction, c. 1862. They were huge, dramatic and extraordinarily ambitious for so small a colony. They were also the one thing in Ottawa that everyone liked.

But the dominant, all-consuming issue in Canadian public life remained sectarianism. To increase the tension, Brown’s call for Representation by Population had become unanswerable. The census for 1861 showed that Upper Canada now had 285,000 more inhabitants than Lower Canada. More and more Conservatives were coming to accept that Upper Canada had to be given more seats in the legislature, in proportion to its population. Cartier—naturally—was adamantly opposed to any change in the balance of seats between Upper and Lower Canada, and Macdonald had to stand in solidarity with him or lose his bleu supporters. Yet rejecting Rep by Pop only magnified the fury in Upper Canada.

A yet-more-radical solution now began to be proposed—to disassemble the Province of Canada and recreate its two original provinces. Each province could then have whatever number of constituencies it wanted, because the two legislatures would be quite separate. But Canada itself would be no more.

Brown, who had begun to assert his authority over both the moderate Reformers and the radical Grits, took up this notion of sundering the nation. An editorial in the Globe threw down the gauntlet: “The disruption of the existing union” was needed to remove Canadien influence over Upper Canada. This would satisfy Lower Canada by giving it “a position of comparative independence.” The alternative would be to “sweep away French power altogether.”*75

Macdonald’s response was defiant. “I am a sincere unionist,” he declared. “I nail my colours to the mast on that great principle.” There had to be both union with Britain and “union of the two Canadas,” he said. “God and nature have joined the two Canadas and no faction should be allowed to sever them.” He had an obvious self-interest in keeping a Canadien bloc onside to compensate for the paucity of Conservative members in Upper Canada. His problem was that a call for compromise and accommodation had none of the mobilizing power of Brown’s war cry for Rep by Pop.

There was only so much that Macdonald—or anyone—could do about sectarianism itself. Any real solution would have to wait for the time when Canadians cared less deeply about their religion, and about the religion of others. On a personal level, though, there was something that Macdonald could do about his sense of malaise, of being unfulfilled, of feeling he was making no mark that he would leave behind: to find a woman to marry who could fulfill him.

In no way did Macdonald take advantage of his widowerhood to gain a reputation similar to that which would later earn his cabinet colleague Charles Tupper the nickname “the Ram of Cumberland.” In the engagingly eccentric book Kingston: The King’s Town (1952), Queen’s University professor James Roy declared flatly that Macdonald “was known to have an amorous disposition,” but provided not a scintilla of proof. As for sex specifically, Macdonald’s prevailing attitude appeared to be that of worldly amusement. Apprised of one minister’s marital misdemeanours, Macdonald responded by quoting the maxim, “There is no wisdom below the belt.” As could be expected, the evidence of Macdonald’s amorous activities as a widower is scanty. Most accounts pass over it in silence. Enough evidence exists, though, to suggest that during this period Macdonald may have had some kind of a relationship with at least five women, and in one instance to have come very close to an offer of marriage.

There’s no question whatever that Macdonald liked women and, as is considerably less common, that he was entirely at ease in their company. In the very practical and rather prosaic Canadian society of the mid-nineteenth century, this alone would have made him a considerable catch. About that society, the visiting Englishwoman Anna Jameson observed, astutely and tartly, “I have never met with so many repining and discontented women as in Canada…. They seem to me perishing of ennui, or from the want of sympathy which they cannot obtain.”

To any woman of spirit, Macdonald, by contrast, would have been catnip. There was his Windsor Castle companion of 1842, Miss Wanklyn, with whom he “sympathized wonderfully.” Later on that same trip, he spent the considerable sum of seven pounds fifteen shillings on a riding whip as a present for an unnamed lady, very likely the same Miss Wanklyn. In 1845, while taking Isabella to Georgia, he sent one letter to Margaret Greene that captures his delight in female company: “I forgot to tell you that Mrs. Robinson, a sweet pretty woman, called on Saturday & I went to find her out today, but the directory was vague & I was stupid and & so did not see her again, much to Isabella’s delight, who says she does not like me taking so much to your lady friends.” That confidence committed to paper, Macdonald became bolder. “I always considered you a Charming Woman, but I did not calculate for all your friends being so. From those I have seen, I have only to say that you will confer a great favor*76 on me by sitting down & writing me letters of credence to every one of your Yankee friends, and it will go hard but I [will] deliver most of them.” It would appear that Isabella had good reason to be glad that Macdonald had failed to say “Hey” to Mrs. Robinson.

That Macdonald understood how to charm women is confirmed by the extraordinary St. Valentine’s Day ball that he organized for February 14, 1860, while living in Quebec City. It was held in the Music Hall of the St. Louis Hotel, the city’s grandest. The chamber was packed with large garlands of roses and graced by busts of Queen Victoria and the Prince of Wales (who was booked to visit the colony later in the year). The walls were adorned with new mirrors everywhere and thirty small wreaths of artificial flowers stitched by the Sisters of Charity. A fountain splashed out eau de cologne. The bill for food and drink came to an incredible $1,600, and the list included sparkling Moselle, sherry, port, ale, porter, and both red and white wine. Close to one thousand guests were invited, and on arrival each lady was presented with a valentine on which Macdonald had penned “very, pretty remarks.” There was music throughout the evening, and dancing far into the night. As a highlight, when an exceptionally large pie was carried into the centre of the room, four and twenty blackbirds flew out from it once it was opened. Macdonald never organized another gala like it again. He was premier, after all, and he had no need to stage an extravaganza to impress local society. In this instance, given the day he chose for the party, it’s entirely possible that he was trying to impress a particular woman.

St. Louis Hotel, Quebec City. It was here, in 1860, that Macdonald staged the splendid, if extravagant, St. Valentine’s Day ball that featured a huge pie from which twenty-four blackbirds emerged.

In fact, after Isabella’s death, Macdonald wouldn’t have had to work hard to impress. His looks remained odd, but he was growing into them. He was self-assured, clever, funny, a delight for any woman to find seated beside her at a dinner table. He also possessed the aphrodisiacal allure of power. His one glaring defect was that he drank far too much—and this may have deterred the woman he came closest to proposing to during this period. She was Susan Agnes Bernard, the daughter of a wealthy Jamaican sugar planter and the sister of Hewitt Bernard, Macdonald’s own top civil servant. They met once by accident in Toronto, then by Bernard’s design in Quebec City, where Susan Agnes was living with her mother. They met there several other times, and it was reported that Macdonald asked her to marry him. Nothing came of it in the end, but Susan Agnes will make another appearance in these pages.

The most intriguing case of a might-have-been involves Elizabeth Hall, herself a widow. Macdonald and her late husband, Judge George B. Hall, had become friends when both of them were freshmen legislature members after the 1844 election. Hall died in 1858, and as a favour Macdonald wound up his estate and set up a trust fund for his children. Macdonald described Hall as “a warm, personal friend,” and Hall, just before he died, wrote to Macdonald to say, “Have had a hard tussle with grim death…. If I don’t see you again may we meet in Heaven.” While settling his friend’s legal affairs, Macdonald saw Elizabeth Hall often. Their relationship continued, and on December 21, 1860, she wrote him a letter that, between some bits of business information, positively aches with her longing for him.

“My loved John,” she began, and then discussed the sale of some of her effects, the progress of the railway being built to Peterborough and the condition of the mails. She used this point to reach right out to Macdonald: “No hope now till I return from the backwoods where I only intend to stay a week & you will have no letter for that time—if that is a privation to you what must I feel if a fortnight without hearing from you. I cannot bear to think of it.” Next came a description of a visit to neighbours, with her added comment: “A lady who was there made a set at me to find out if I was to be married in [the] Spring & I told her it was rumour, & my mother advised me when setting out in life to believe ‘nothing I heard & only half of what I saw.’” Finally, she noted that the horses were being readied to take her for a drive, followed by a confident—or perhaps an overconfident—“Goodbye my own darling—love from loving Lizzie.”

Unquestionably, something was going on between Macdonald and Elizabeth Hall. Most commentators have assumed that it was principally in Elizabeth’s mind and that she made the mistake of pressing Macdonald too hard and lost him. Perhaps not, though; perhaps the opposite happened. What is truly fascinating about Elizabeth’s letter is that it should exist at all. Macdonald kept very few personal letters, and none at all from either of his wives or from his mother. That he should have kept this one, hanging on to it for more than a quarter-century, suggests some recognition of a lost chance. Perhaps nothing happened because, with several children to bring up, Elizabeth Hall had too many dependants for him to cope with. She would, though, have already been well aware of his drinking “vice,” and she possessed the invaluable asset of experience as the wife of a public man. So perhaps Macdonald let happiness slip through his fingers out of ineptitude or timidity.

Two of the other women are only wraithlike figures. There were rumours that the sister of a Prince Edward Island politician might marry him, but nothing came of the affair. And, at the close of a routine October 29, 1861, letter to one Richard William Scott, Macdonald added the tantalizing postscript: “P.S. You can make love to Polly.” Here, Macdonald appears to have been telling Scott that whatever may once have passed between him and the semi-anonymous Polly, the way was now open for Scott to press his own suit.

Then there is Eliza Grimason.

Two writers, Patricia Phenix, the author of Private Demons, and more tentatively Lena Newman, the author of the excellent 1974 coffee-table book The John A. Macdonald Album, have suggested that a physical relationship may have existed between Macdonald and the lady. Eliza Grimason was a remarkable woman, and there’s no question she adored Macdonald. No beauty by even the most generous estimate, but strong and confident, she owned and managed Grimason House, Kingston’s leading tavern.*77 She performed this role with such aplomb that, having started as an illiterate Irish immigrant, she went on to own properties with the handsome value of fifty thousand dollars. When they first met, she was just sixteen and he had turned thirty. Her husband, Henry, bought the property that became the tavern from Macdonald; when Henry died eleven years later, Macdonald did not press her for the balance of the payments, knowing she had three children to bring up.

Eliza Grimason, owner of the tavern in Kingston that Macdonald frequented. Rumours of a relationship between them were almost certainly untrue, but, even though they were from totally different social backgrounds, they were lifelong close friends.

Under her management, Grimason House became the most popular place in the town. It also became Macdonald’s unofficial campaign headquarters. In one description, admittedly from the suspect source of James Roy, it was “the shrine of John A.’s worshippers with Mrs. Grimason as high priestess.” The place was crowded, raucous, rowdy and raunchy. Macdonald went there regularly, bantering with the customers (mostly Conservatives), watching the cockfights (though not himself betting on them) and drinking a great deal. Election nights were his night. Eliza Grimason reportedly controlled one hundred votes, and she made her van available to take Conservatives to the polls, held “open house” for workers and voters and contributed to his campaign funds. According to Macdonald’s early biographer Biggar, “when the returns were brought in, she would appear at Sir John’s committee room, and walk up among the men to the head of the tables, and, giving Sir John a kiss, retire without saying a word.” On the one occasion he lost, she was devastated. “There’s not a man like him in the livin’ earth,” she said.

Many years later, Eliza Grimason came to Ottawa as Macdonald’s guest at the opening of Parliament. He toured her round the buildings. Then she went to Earnscliffe to have tea with Lady Macdonald, whom Eliza judged “a very plain woman” but doing the job that needed to be done, because “she takes very good care of him.” It’s just not credible that Macdonald would have taken a former mistress around Parliament and then handed her on to have tea with his wife. The kiss she gave him in his committee rooms after he won each election must have been innocent, or the half-tipsy Conservative ward-heelers would have been shocked and, incomparably worse, they would have talked.

Macdonald’s character, though, gave his friendship with Eliza Grimason a dimension that was far less common and far more interesting than any illicit relationship between them would have been. Their friendship was an extraordinarily democratic one. Macdonald, the nation’s most powerful man, and a highly intelligent and well-read one to boot, was the true friend of a rough countrywoman who earned her living running a grungy tavern. Their friendship was so close, and so unaffected, that Macdonald in later years kept a framed photograph of Mrs. Grimason on his desk, beside one of his mother. It was because Macdonald knew people like Mrs. Grimason and her customers that he knew Canada better than any succeeding premier or prime minister ever did.

Maybe, post-Isabella, Macdonald could not allow himself to be close to another woman. One chronicler, the historian Keith Johnson, has written that Macdonald seemed to have a “central, emotional dead spot.” That’s too strong an assessment; all his life he could be extraordinarily tender with children and wholly at ease with them. But except for Isabella during their first few years together, he never again really let down his guard with a woman.

Here, as always with Macdonald, there is a glaring contradiction—although perhaps only an apparent one. Women adored him. That was the judgment of that sophisticated observer Sir John Willison, the editor of the Globe, who wrote in his Reminiscences that “because women know men better than they know themselves and better than men ever suspect, there was among women a passionate devotion to Sir John A. Macdonald such as no other political leader in Canada has inspired.” (Since Willison was a confidante of Laurier, this was high praise indeed.) Willison ends, with the gallant flourish, “No man of ignoble quality ever commands the devotion of women.”

One other aspect of Macdonald’s relations with women deserves some attention, if cautiously so. In an essay on Macdonald in the 1967–68 edition of the Dalhousie Review, the historian Peter Waite first remarks that “his liking for human beings was genuine” and then goes on to make the intriguing comment, “It is not too much to say that he often liked men as much for their bad qualities as for their good.” A readiness to like people for their faults, or at least an acceptance that such failings are an integral part of the human condition, is more a female trait than a male one. In his own person, Macdonald was thoroughly masculine: he drank a lot, told bawdy stories, had a nasty temper and was highly competitive. But there was also a female side to his nature—an aspect of him caught by the novelist Hugh MacLennan’s comment quoted in the introduction, “This utterly masculine man with so much woman in him.” Whatever his own nature, he took people as they came and worked with their faults and shortcomings, rather than trying to reform them or to improve them. As well, the failings of human beings provided him with invaluable raw material for the endless anecdotes by which he gently tugged self-doubting opponents into his web.

Whatever his qualities, Macdonald, during the years on either side of 1860, succeeded neither with women nor with sectarianism. Perhaps he did win one signal victory over the latter challenge, though proof is impossible. A fascinating document exists that captures the essence of the policy of compromise and accommodation that Macdonald deployed to try to resolve the deeply divisive issue of sectarianism that so disfigured Canadian politics through the 1850s and early 1860s.

In a long dispatch to the colonial secretary in June 1857, the governor general, Sir Edmund Head, wrote, “If it is difficult for any statesman to stem their [sic] way amid the mingled interests and conflicting opinions of Catholic and Protestant, Upper and Lower Canadian, French and English, Scotch and Irish, constantly crossing and thwarting one another, it is probably to the action of these very cross interests and these conflicting opinions that the whole united province will, under providence, in the end owe its liberal policy and its final success.” Head added, “In such circumstances, constitutional and parliamentary government cannot be carried on except by a vigilant and careful attention to the reasonable demands of all races and all religious interests.”

To that analysis of Canada’s essential nature, there was not a word Macdonald would have wanted to add. He may indeed have helped to compose many of them. He and Head had several long, private conversations when the government was located in Toronto. Pope wrote in his biography that Macdonald was “never so intimate with any Governor-General as with Sir Edmund.” Moreover, the governor general needed to learn from Macdonald; when he first arrived in 1855, Head caused an uproar among Canadiens by commenting to an Upper Canadian audience on “the superiority of the race from which most of you have sprung.”

If Head learned from Macdonald, the reverse was not true. In another dispatch home in 1858, Head suggested a federation of all the British American colonies. To Macdonald, such an idea was but an intellectual abstraction—perhaps nice, but irrelevant because undoable.

By this time Macdonald was well aware that something was fundamentally amiss in Canadian politics and governance. But he still had no idea what to do to cure the malaise. Around him, though, the times had begun to change.