NINETEEN

Parliament vs the People

If we do not represent the people of Canada, we have no right to be here. John A. Macdonald

The sweeping success of the Quebec Conference was followed by the double afterglow of a triumphal tour of Canada by the Maritime delegates and the plaudits for the accomplishment expressed by British newspapers from the Times on down. Macdonald’s response to all this praise was to go on a prolonged binge. He performed like a tightly wound spring that, once released, flies all over the place and then collapses in a heap.

The post-conference tour, which had the dual purpose of showing Canada to the Maritimers and showing off the Maritimers to Canadians, began in Montreal with a gala dinner hosted by Cartier. To encourage the delegates to complete their good work, the program of toasts included the verse “Then let us be firm and united / One country, one flag for us all; / United, our strength will be freedom / Divided, we each of us fall.” The cavalcade then moved to Ottawa, where Macdonald was to act as host. It began well: the crowds were huge and they escorted the visitors in a torchlight procession to the Russell Hotel, where they were to dine. As the gala’s principal speaker, Macdonald got to his feet, said a few words, then stopped and fell silent.*128 Galt had to fill up the vacuum with an extemporaneous speech. Macdonald rejoined the group when it left by train for Kingston, with succeeding stops planned at all the communities—Belleville, Cobourg, Port Hope—on the way to Toronto, where Brown would be host. But Macdonald never left Kingston. It’s safe to guess that he spent most of his time at Eliza Grimason’s tavern, periodically collapsing into the bed kept for him there.

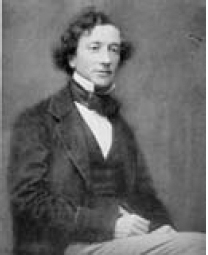

As all who knew him realized well, Macdonald, from this period on, would every now and then go on one of these binges and be unable to do anything until they were over. Then suddenly he would reappear as though nothing had happened, as full of vigour and zest as ever. His constitution was a minor marvel. Macdonald did enjoy walking, but he never undertook any strenuous exercise. He ate lightly, not because he drank heavily as is frequently the case, but because he always ate lightly. A photograph of Macdonald taken at around this time—in 1863 by the famed William Notman of Montreal, and the front cover of this book—portrays him as lean and fit and impressively erect.†129 The photo also captures perfectly the distinctive quality of his eyes—amused, observant, commanding. It may have been Notman’s magic (all the more magical because he used only natural light), but absolutely nothing about the photo suggests a public figure with a single care in the world, least of all that of his having become, if irregularly, an out-of-control public drunk.

After Macdonald had finished wrestling with whatever devils were assailing him, he went right back to the job at hand. With the Quebec Conference over and a constitution agreed on, the way ahead was clear. Macdonald needed now to get approval for the Confederation scheme first from Canada’s legislature, and then from the legislatures of the key Maritime provinces, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. As the climactic step, he needed the approval of the Parliament at Westminster. Thereafter, he could come back home with Confederation’s constitution in his pocket.

One intervening step was required, though. The British press had indeed been laudatory, but it had also expressed some disquieting notes. The Edinburgh Review, while applauding the accomplishment, had gone on to describe it as the “harbinger of the future and complete independence of British North America,” while the Saturday Review judged the achievement as “not so much a step towards independence as a means of softening the inevitable shock.” The Times, in its more orotund way, declared that while “nothing could be more in correspondence with the interests and wishes of this country” than Confederation, nevertheless “the dependency that wishes to quit us has only to make up its mind to that effect.” What Macdonald needed, then, was an official stamp of approval to Confederation from the Imperial government that could be waved in front of the Canadian and Maritime legislatures, and, as an additional reassurance, a cessation of talk in London about possible Canadian independence.

For this vital but delicate mission, Macdonald chose Brown. It was a deft choice. Brown’s key qualifications were that he wasn’t Macdonald and that he was the leader of Canada’s largest party. He would carry in his person to London the message that support for Confederation was widespread. He would also allow Macdonald to get on with his immediate task of assembling the legislature and of figuring out how to secure as quickly as possible its agreement to the scheme.

For Brown, this transatlantic trip had to be one of the most agreeable he ever made, not least because Anne went along with him. They travelled first to Edinburgh, and then Brown went on alone to London.

On December 3, 1864, Brown called on the colonial secretary, Edward Cardwell, who received him almost as a brother. Cardwell had already drafted a memorandum setting out his views on the Quebec Resolutions; this, if Brown approved of it, he intended to dispatch to the governor general in Ottawa and to the Maritime lieutenant-governors. Brown not only approved but was ecstatic. “A most gracious answer to our constitutional scheme. Nothing could be more laudatory—it praises our statesmanlike discretion, loyalty and so on,” he wrote afterwards to Macdonald.

Cardwell had one more bit of news of even greater import to pass on. Confederation, he told Brown, was a subject “of great interest…in the highest circles.” Brown immediately picked up the reference that Queen Victoria herself wanted Confederation for her distant colonies. He was so overcome by this confidence that he asked whether the Queen might come to Canada to open the first post-Confederation Parliament. Cardwell’s reply, no doubt couched in the correct circumlocutory phrases, was that Victoria, a grieving widow ever since the recent death of her beloved Prince Albert, was so emotionally shattered that it was “totally out of the question” for her even to open Parliament in next-door Westminster.

Nothing else was denied Brown, and so by extension Canada’s Confederates. He went to Prime Minister Lord Palmerston’s country house in Hampshire and took a long stroll with the prime minister through the gardens. He met the foreign secretary and the rising political titan and fellow-Liberal William Gladstone. A bit carried away, Brown afterwards told Anne of his encounter with Gladstone: “Though we had been discussing the highest questions of statesmanship—he did not by any means drag me out of my depth.” Then hastily he added, “Don’t for any sake read this to Tom or Willie, or they will think I have gone daft.”

Brown did have one concern to report to Macdonald: “There is a manifest desire in almost every quarter that ere long the British colonies should shift for themselves, and in some quarters evident regret that we did not declare at once for independence.” The cause, Brown said, was “the fear of invasion of Canada by the United States,” an affront that might compel Britain, for the sake of honour and of face, to make the futile gesture of intervening to try to save its colony. In fact Brown and Macdonald would have been even more concerned had they known of a letter sent at this time to Governor General Monck by the junior minister for the colonies, C.B. Adderley. In it, he reported, “Gladstone said to me the other day: ‘Canada is England’s weakness, till the last British soldier is brought away & Canada left on her own. We cannot hold our own with the United States.’”

Britain was onside all right, but in its own way.

Brown landed back in Canada on January 13, 1865. Two days earlier, Macdonald had passed a significant milestone—he’d reached the age of fifty. He either paid no attention to his birthday or marked it by consuming a bottle in his room in some boarding house. But for cronies, Macdonald was now alone. Hugh John, at the age of fifteen, was distant from his father, both because he had been brought up by Margaret and James Williamson in Kingston and because he was now beginning to feel the strain of being the son of a famous father. That fall, Hugh John entered the University of Toronto as an undergraduate.*130

At this same time Macdonald was becoming increasingly concerned about the condition of his law practice. His law partner Archibald Macdonnell had died the previous spring, and ever since Macdonald had been discovering just how deeply his company was in debt, with some of the debts resulting from transactions of highly questionable probity, but for which he would be personally responsible. Brown, in one letter to Anne at this time, confided that “John A.’s business affairs are in sad disorder, and need more close attention.”†131

Macdonald’s two escapes from solitude now were the Confederation project and drink.

Macdonald in his prime. This photo was taken by the famous William Notman of Montreal in 1863. The two minutes of motionlessness required for a photograph at the time did nothing to dim his energy and vivacity.

The Legislative Assembly met unusually early that year—on January 17, following Macdonald’s request to Governor General Monck. The members would need the extra time to debate and, all going well, approve the seventy-two Quebec Resolutions. Thereafter would come the debates in the New Brunswick and Nova Scotia legislatures about the same draft resolutions to establish Confederation.

As if in anticipation of his impending triumph, Macdonald was advised of a tribute soon to be extended to him—he was to be given an honorary degree by Oxford University, the first Canadian to be so recognized.*132 It is probable, although not certain, that Monck also gave Macdonald early notice that, when it came time to form a government for the new nation (in about a year, it was generally expected), he would invite him to be its first prime minister. At Quebec City, Macdonald had raised himself to the status of the irreplaceable man; he was about to become the man.

About winning approval of the draft constitution from Canada’s Legislative Assembly, Macdonald had no qualms. “Canada on the whole seems to take up the scheme warmly,” he wrote to Tilley. About opinion in his own Upper Canada, he was absolutely right: the only naysayers were a few Tory Conservatives worried that Confederation might weaken the country’s ties to Britain. In Lower Canada the prospects were more mixed, yet still predominantly positive. Rouge leader Antoine-Aimé Dorion had already published an anti-Confederation manifesto charging that the Quebec Resolutions would produce not a “true confederation” of sovereign provinces but a disguised legislative union in which the provinces would be mere municipalities and so unable to protect their electorates. As an example of the way Confederation lurched along, one step forward, one back, Galt at this same time was reassuring audiences of his fellow Lower Canada English-speakers that, precisely because the provinces would be merely “municipalities of larger growth,” controlled by a strong central government, there was no need for them to worry about being reduced to a minority in a French-dominated province. Fortunately, none of Cartier’s bleu members had blinked at any of these concerns, and this was all that really mattered in Lower Canada—soon to become Quebec.

And then some of them did blink. The cause wasn’t a real problem but an apparent one—in politics, no different from a real problem. The Throne Speech read by Monck at the opening of the legislature included a call for Canadians to “create a new nationality.” This ambition was logical enough: everywhere, the reason for creating new nations, as in Italy, which had come into existence just four years earlier, was either to create a new nationality or to liberate an old one from oppression. McGee had been calling for years for a “new nationality.” During the Quebec Conference, Prince Edward Island delegate Edward Whelan had got so caught up in the national vision that he dismissed his own province as “a patch of sandbank in the Gulf.” Even the cautious Oliver Mowat got into the nationalist spirit, although his exuberance may have been for show because, right after the conference, he announced he was leaving politics to become a judge in the chancery court. (Macdonald filled the vacant Reform cabinet slot by appointing the little-known W.P. Howland.)

The problem was that all this talk about a Canadian nation and a Canadian nationality threatened the national distinctiveness of Canadiens. Adroitly, Dorion moved a resolution calling on members to disavow plans for a new nationality. It was defeated, predictably, but it gained the support of twenty-five French-Canadian members. If Dorion could find another hot button, he might yet be able to whip up an anti-Confederate storm in Quebec.

On February 3, Macdonald moved that the House adopt the Quebec Resolutions. He made a brief explanatory statement, following up three days later with a two-hour speech. Subsequently, all the leading pro-Confederates—Brown, Cartier, Galt and McGee—had their say, as well as some of the far smaller number of anti-Confederates, notably rouge leader Dorion and Independent Conservative Christopher Dunkin. All these words, filling 1,032 double-columned pages, became known as the Confederation Debates.

It was in his short statement that Macdonald made his key new contribution to the Confederation project. He had already anticipated the now well-known difficulty of implementing a new constitution or of making major changes to an existing one: that all those unhappy for any reason particular to themselves can vote No, and that all the Noes may add up to a deal-breaking majority, even though the reasons for many of them contradict each other. In Canada—inevitably—there was a further problem. Any division in an overall vote on a constitution can cause frictions to national harmony; a division caused by confrontations between races or religions, though, can shatter national unity. Two values were thus put into conflict—democracy and national unity. Macdonald’s choice, naturally, was for national unity over democracy.

In his statement of February 3, Macdonald set out first to reduce to a minimum the extent of the legislature’s debate on the constitution. Rather than a discussion and a vote on each of the seventy-two clauses, there should be only a single vote, for or against the entire document.*133 The entire Confederation package “was in the nature of a treaty,” he said;†134each of its clauses had already been fully discussed and either agreed to or amended after compromises. “If the scheme was not now adopted in all its principal details as presented to the House,” he informed the members, “we could not expect it to be passed this century.”

That mission accomplished, Macdonald moved on to his main argument: approval by the legislature’s members was all that was needed for the constitution to be passed. “If this measure received the support of the House,” he said, “there would be no necessity of going back to the people.” There was no need, that is, for the people to say what they felt, either in an election or in a plebiscite.

That Macdonald wanted to avoid delay and division was the immediate, practical motive for his stance. But it was by no means the only one. He believed also, entirely genuinely, that the decision was the exclusive responsibility of the members of Parliament whom the people had elected to represent them, rather than that of the public at large. Canada’s constitution was to be for the people, but not of the people.

On the same day that he spoke, Macdonald sent a letter to a supporter, John Beattie, setting out the philosophical justification for his policy. The constitutional package, he pointed out, had received “general if not universal favour.” The government had the right, therefore, “to assume, as well as the Legislature, that the scheme, in principle meets with the approbation of the Country, and as it would be obviously absurd to submit the complicated details of such a measure to the people, it is not proposed to seek their sanction.”

Today, after the Meech Lake and the Charlottetown accords, no politician would advance such an argument, except one wishing to commit instant political suicide. Oddly, though, the constitutional change cherished most highly by the majority of Canadians, that of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, was never submitted for approval in a referendum.

In the mid-nineteenth century, however, nothing that Macdonald said was in any way novel or shocking. Then, representative democracy was the norm. He was taking his stand on the side Edmund Burke had taken in his famous declaration to the electors of Bristol: “Your representative owes you, not his industry only, but his judgment; and he betrays, instead of serving you, if he sacrifices it to your opinion.” It was the duty of elected members to make the decisions they judged the best; it was the duty of voters to elect those they judged best able to make those decisions.

Today, most of that is an archaism. On almost all occasions now, MPs make the decisions that their party has already decided they should make. Voters today insist on contributing themselves—the system is known as direct democracy—to the making and the implementing of decisions. It could be said that the era of the divine right of kings was followed, comparatively briefly, by an era of the divine right of Parliament, and this is now giving way to an era of the divine right of the people.

The mid-nineteenth century, though, was still the era of parliamentary supremacy. The Canadian version of it might have been small and parochial, yet it was a branch of the majestic Mother of Parliaments in London stretching back, often gloriously, at times bloodily, over the centuries. And the Canadian version had won for its people the great victory of Responsible Government. Its debates were widely followed, and reported nearly in full, in the newspapers. Its leading men—Macdonald, Cartier, Brown and McGee—were national celebrities, the only ones there were then. The widespread distaste for “partyism,” or for disciplined, organized parties, reflected the presumption that individual members would—certainly should—speak out for and vote for their personal beliefs, even their conscience, rather than just the partisan interests of their party. The doctrine of parliamentary supremacy was as much a part of all people’s upbringing as were the doctrines of their particular Christian faith. When Macdonald said, “Parliament is a grand inquest with the right to inquire into anything and everything,” everyone, except perhaps the dwindling number of populist Grits, would have agreed.

The alternative doctrine of democracy not only had few supporters but was widely suspect. A prime reason was that democracy was an American idea. To Canadians, what was happening south of the border was not democracy but mob rule. Canadians, by contrast, assumed that they themselves enjoyed real liberty because their ultimate ruler was a constitutional monarch rather than an elected president who might become a dictator. That their head of state was essentially powerless was the reason, so hard for Americans to comprehend, why anti-democratic Canadians were genuinely convinced that they enjoyed more real freedom and liberty than their neighbours. Nor were critics of democracy without good arguments: in France it had led to the Terror, then to the dictatorship of Napoleon; in the United States, to the Revolution, then to the Civil War. And Macdonald’s arguments were persuasive. The Confederation project had got this far only because of “a very happy concurrence of circumstances which might not easily come again.” He appealed to members to “sacrifice their individual opinions as to particular details, if satisfied with the government that the scheme as a whole was for the benefit and prosperity of the people of Canada.”

As thought Macdonald, so did almost everyone else. If, in Macdonald’s judgment, Americans were subject to “the tyranny of mere numbers,” to the Toronto Leader U.S. presidents were “the slave of the rabble,” to the Globe democracy was “one of those dreadful American heresies,” and to Brown American elections were a sham, because “the balance of power is held by the ignorant unreasoning mass.” McGee, during his speech in the Confederation Debates, said, “The proposed Confederation will enable us to bear up shoulder to shoulder, to resist the spread of this universal democracy doctrine.” In Lower Canada politicians thought the same way; so, still more vociferously, did the Catholic hierarchy. In Canada there were conspicuously no great debates about democracy as there had been in Britain during each of its Reform Laws.*135

There nevertheless was a debate in Canada’s Legislative Assembly about whether a constitution should be sanctioned by the people or only by those few who happened to be members of the legislature. A Reform backbencher, James O’Halloran, addressed the issue directly. “When we assume the power to deal with this question, to change the whole system of government, to effect a revolution peaceful though it may be, without reference to the will of the people of this country,” he said, “we arrogate to ourselves a right never conferred upon us, and our act is a usurpation.” He went on, describing the people as “the only rightful source of political power.” Another backbencher, Benjamin Seymour, supported O’Halloran,*136 as did a few newspapers, such as the Hamilton Times, which declared forthrightly, “If their [the people’s] direct decision on the confederation question is unnecessary…we can imagine none in the future of sufficient importance to justify an appeal to them. The polling booths thereafter may as well be turned into pig-pens, and the voters lists cut into pipe-lighters.”

A second debate on the issue of democracy occurred after the Confederation Debates had ended, when a Conservative member, John Hillyard Cameron, moved a motion calling for an election to be held before the constitution was enacted. The motion was defeated easily. The brief debate that followed, though, inspired Macdonald to muster his most extended and considered arguments to justify parliamentary supremacy over the will of the people.

The only way to determine the people’s will on a single issue would be to hold a referendum, declared Macdonald. In a letter to a supporter, Saumel Amsden, he argued that a referendum would be “unconstitutional and anti-British” anyway, “submission of the complicated details to the Country is an obvious absurdity.” In the Parliament, he based his argument on the nature of Parliament itself. “We in this house” he told the members, “are representatives of the people, not mere delegates, and to pass such a law would be robbing ourselves of the character of representatives.” The idea itself was dangerous, because “a despot, an absolute monarch” could use referendums to win public approval “for the laws necessary to support a continuation of his usurpation.” The strength of Macdonald’s feelings came through in his unaccustomed eloquence: “If the members of this house do not represent the country—all its interest, classes and communities—it never has been represented. If we represent the people of Canada…then we are here to pass laws for the peace, welfare and good government of the country…. If we do not represent the people of Canada, we have no right to be here.”*137 Macdonald genuinely believed what he was saying; as a desirable bonus, his argument ensured that the Quebec Resolutions would be approved as quickly as possible.†138

One other factor may have influenced Macdonald’s arguments against democracy: he knew that referendums produce losers as well as winners, and that turning some people into losers always comes at a cost. Macdonald had anticipated this point in the speech he delivered at the beginning of the conference in Quebec City. The effect of the constitution, he told the delegates, would be to create “a strong and lasting government under which we can work out our constitutional liberty as opposed to democracy, and be able to protect the minority by having a powerful central government…. The people of every section must feel they are protected.” One of the constitution’s purposes would be specifically to protect minorities—religious, ethnic and linguistic. Here Macdonald was feeling his way towards the thoroughly modern and pre-eminently Canadian concept that democracy must balance its own defining rule—the will of the majority—with the needs, and the rights, of minorities.

Contemporary sensibilities are still bruised by Macdonald’s exclusion of Canadians from any say in making their own constitution. If he had included them, though, it might not have made that decisive a difference. Then, no more than 15 per cent of adults in Canada had the vote. And the turnout might well have been low. A systematic search of Macdonald’s correspondence during the key years of 1864 and 1865 reveals how few letters he sent out expressing his views about and arguments for the constitution. The explanation is disconcerting: he wrote few letters about the constitution because he received very few asking for his thoughts. The truth is that at the same time they were excluded from constitution making, Canadians willingly excluded themselves. Moreover, there was always the risk that a referendum might indeed have made a decisive difference: Confederation might well have lost.

Macdonald’s main speech, two hours in length, given on February 6, wasn’t one of his best. He was tired, suffering an illness of some kind that was caused or exacerbated by heavy drinking. Anyway, he had said everything many times before. He declared that he had always favoured a legislative union—“the best, the cheapest, the most vigorous, and the strongest system of government we could adopt”—but accepted that a federation of some kind was needed to protect “the individuality of Lower Canada.” In addition, both of the Maritime provinces now committed to Confederation were not prepared to “lose their individuality as separate political organizations.”

He did broach one fresh topic of potentially great importance. Some Canadians, Macdonald noted, opposed Confederation out of fear that “it is an advance towards independence.” He himself had no such concern; he did, though, expect the transatlantic relationship to change. “The colonies are now in a transition state. Gradually a different colonial system is being developed—and it will become[,] year by year, less a case of dependence on our part, and of overruling protection on the part of the Mother Country, and more a case of healthy and cordial alliance. Instead of looking on us as a merely dependent colony, England will have in us a friendly nation to stand by her in North America in peace or in war.”

Among all the speakers in the six-week debate, no one identified the dilemma inherent in Canada’s ongoing relationship with Britain with more devastating accuracy than Christopher Dunkin.*139 Small and whip-smart—perhaps too smart for his own good, because he generated more bright ideas than his hearers could absorb—Dunkin asked rhetorically, “What are we doing? Creating a new nationality, according to the advocates of this scheme. I hardly know whether we are to take the phrase as ironical or not. It is a reminder that, in fact, we have no sort of nationality at all about us…. Unlike the people of the United States, we are to have no foreign relations at all to look after…therefore, our new nationality, if we could create it, could be nothing but a name.” Cruelly, but unanswerably, Dunkin commented, “Half a dozen colonies federated are but a federated colony after all.”

In response to the contradiction identified by Dunkin—of creating a nation that would have no nationality—Cartier did his best, very possibly, since he was no intellectual, by repeating ideas suggested to him by Macdonald. “When we were united together, if union were attained, we would form a political nationality, with which neither the national origin nor the religion of any individual would interfere,” said Cartier. Some complained that Canada was too diverse, but, he continued, “the idea of unity of races was utopian—it was impossible. Distinctions of this kind would always exist. Dissimilarity in fact appeared to be the order of the physical world, of the moral world, as well as in the political world.” Britain itself was composed of several nations. Likewise in Canada, the English, French, Irish and Scots would each, by their “efforts and success[,] increase the prosperity and glory of the new confederacy.” In his rough way, Cartier was talking about a nation whose unity would be its diversity.

Cartier’s principal purpose was to mollify Quebecers’ anxieties about a “new nationality.” Nevertheless, his comments were one of perhaps only two genuinely original insights to emerge during the prolonged debate. The other insight has almost vanished from the history books, but it merits being revived. Its author, Alexander Mackenzie, that worthy but dull rawboned Scot, later a Liberal prime minister, commented in the midst of an otherwise routine speech, “I do not think the federal system is necessarily a weak one, but it is a system which requires a large degree of intelligence and political knowledge on the part of the people.”

As the days passed, it became clear that those opposed to the scheme, principally the rouges, had nothing to suggest in its place. A mood of inevitability took hold. At times, there were only twenty members in the chamber. In the description of the Stratford Beacon, the House had deteriorated to “an unmistakably seedy condition, having as it was positively declared, eaten the saloon keeper clean out, drunk him entirely out, and got all the fitful naps of sleep that the benches along the passages could be made to yield.”

The vote on the main motion was called at last, at 4:30 a.m. on Saturday, March 11, 1865. The result was 99 to 33. The Nays included nineteen French Canadians—a half-dozen fewer than those who had voted six weeks earlier for Dorion’s motion opposing a “new nationality.”

Except for the legislatures in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, Confederation was now a done deal.

Four weeks later, the long agony south of the border ended when General Robert E. Lee called on Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, bringing with him the signed surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia. Thereafter, the North began demobilizing its vast armies with remarkable speed. Fear of an invasion northwards receded rapidly, in Canada as well as in Britain. In Macdonald’s judgment, either the huge Northern armies, “full of fight,” would invade almost immediately or, if not, “we may look for peace for a series of years.”

One substantive concern did remain. Among those soon to be released from the Northern armies were tens of thousands of Irishmen, all now trained in the arts of war. A new word entered the Canadian political vocabulary—Fenian (from the Fenian Brotherhood, originally created in 1858 for the purpose of liberating Ireland). Macdonald charged his intelligence chief, Gilbert McMicken, to keep a close eye for any possible cross-border raids. He took seriously the declarations by Fenian leaders that one effective way to deliver a blow at Britain would be to attack the lightly guarded Canada. “The movement must not be despised,” he wrote to Monck. “I shall spare no expense in watching them.”

Before the Confederation Debates ended, other news—this time deeply discouraging—reached Macdonald. It came from New Brunswick’s small capital of Fredericton. The result of a provincial election there, even though not yet completed, was almost certainly going to be the defeat of Premier Leonard Tilley’s pro-Confederation government. Shortly afterwards, Nova Scotia’s premier, Charles Tupper, sent word to Macdonald that support for Confederation was slipping fast there.

Patching these pieces back together now became Macdonald’s principal mission. It would remain so for far longer than he, or anyone, imagined.