TWENTY-ONE

The Turn of the Screw

The left arm is then extended a little, and the Queen laid her hand upon it which I touched slightly with my lips. Alexander Tilloch Galt, describing his presentation to the Queen

Sometime in the spring of 1865, Macdonald figured out how to haul the Maritime provinces onto the side of Confederation. He would appeal to their sentiments about Britain. To do that, a Fathers of Confederation mission would call upon the Great White Mother.

No real reason existed for Macdonald and the other Canadian leaders to go over to London. In the legislature, Macdonald described the group’s purpose as “to take stock…with the British Government”—about as vague a description as he could concoct. For a time Macdonald even protested that he was too busy to go. This excuse was blatantly untrue, because he was due to go to Oxford to collect his treasured honorary degree. But once Macdonald had committed himself to the trip, a doubting Brown agreed to go along as well. The actual topics to be discussed while they were in London were not easy to compile: the Imperial government had already made clear its wholehearted support for Confederation, and although there were defence matters to go over—the Canadian government had just voted one million dollars for new defence works—no one in London had the least interest in provoking the United States by new military projects. Nevertheless, off went the Big Four—first Cartier and Galt in a ship that made a stopover in Halifax, giving them time for discussions on railway matters there, and then Macdonald and Brown shortly afterwards on a different vessel. The real purpose of their mission was to use the Imperial government to get the Maritimers to turn around and face in the right direction.

The softening process has already begun. The colonial secretary, Edward Cardwell, after his meeting with Brown the previous December, had dispatched to Canada the laudatory memorandum on Confederation that had so pleased his visitor. Still more useful was the covering note attached by Cardwell to the copies he sent to the Maritime lieutenant-governors. “Our official dispatch,” he wrote to Arthur Gordon in New Brunswick, “will show you that Her Majesty’s Government wish you to give the whole [Confederation] scheme all the support and assistance in your power.” Britain’s general policy, he explained, was “to turn the screw as hard as will be useful, but not harder.” Two discrete turns of the screw were then applied. Gordon was reminded that his career depended on his shepherding New Brunswickers towards voting for Confederation. His counterpart in Nova Scotia, Sir Richard MacDonnell, who had made no secret of his opposition to Confederation, was pulled out completely and sent to Hong Kong. He was replaced by a soldier hero, Sir William Fenwick Williams, who knew how to take orders. Less successfully, Prince Edward Islanders were warned that the bill for the salary of their lieutenant-governor might be transferred from London to Charlottetown, but this pressure made them only more truculent than they already were.

For the Big Four, the reception in London was at least as agreeable as had been the earlier one for Brown alone. The Colonial Office chose the moment of Macdonald’s arrival to send word to the Maritime capitals that Maritime Union was no longer discussible; all that was left on the Maritimes’ negotiating table, therefore, was Confederation.

The quartet did have diligent discussions with the appropriate British politicians on matters such as defence, Confederation, the prospects for Canada’s renewing the Reciprocity Treaty with the United States and the future of the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North-West. At the only meeting that actually mattered, none of these topics was raised. That was the meeting with Her Majesty.

On May 18 the four went excitedly to Buckingham Palace in a carriage that picked them up at the Westminster Palace Hotel. On arriving, they discovered, to their mixed pride and terror, that Queen Victoria had asked for them to be presented first. “Dukes and Duchesses had to give way and open up a passage to us,” Brown reported to Anne. The procedure that followed was a trifle more complicated: it involved, as Galt described it to his wife, going “down on the right knee (a matter involving, in my own case, a slight mental doubt as to the tenacity of my breeches), the left arm is then extended a little, and the Queen laid her hand upon it which I touched slightly with my lips.” That ordeal completed, the quartet was kept together so the Queen could engage them in small talk, including an exchange with Cartier in French. Then she glided away.

Back across the Atlantic went a report that amounted to a command: Her Majesty and her Canadian ministers were as one.

Earlier, the four had spent little time at the Westminster Palace Hotel, because night after night they were out dining at the mansions of dukes and lords and cabinet ministers and railway magnates, or they went to balls where coiffed, bare-shouldered ladies exhibited a remarkable interest in the details of Canadian politics, economics and culture. No less deeply interested in Canadian doings was the Prince of Wales. He had them over to dinner at Buckingham Palace, drew them into an inside room filled with a specially selected group of one hundred of the two thousand guests, and while chatting with them smoked cigars and showed off his new Turkish dressing gown. (In an exercise in re-gifting, Galt was given one of these cigars, which earlier had been presented to the prince by the King of Portugal.) Less interested in the Canadians and in Canada was Bishop Wilberforce, who, as Brown reported to Anne, asked “whether Darwin believed that ‘turnips are tending to become men.’”

Queen Victoria. The last British monarch with real political influence, she used it to give Confederation the push it needed to overcome Maritime opposition.

They also went to the Epsom Downs on Derby Day, taking with them a hamper of food and wine from Fortnum and Mason. The Times’s famed war correspondent from the Crimean War, William Russell, took them around, getting them into one of the most socially fashionable of tents, where they sipped turtle soup and champagne cup. They took in the races (Macdonald won twenty guineas) and gazed, as Galt reported to his wife, at “the sights of the course, gypsies, music, mountebanks, games of all kinds, menageries of savage animals, and shows of Irishmen disguised as savage Indians.” On the jam-packed road driving back, they used the roof of their carriage as a mobile platform from which to fire dried peas through a peashooter at passersby, who, as was customary, fired back balls of flour. Brown and Macdonald also went together to the opera Lucrezia Borgia.

That was it. Official replies to their queries about specifics such as defence were exasperatingly vague. There was one significant shift in their own attitudes, though. The people they had met, Brown reported home, “are a different race from us, different ideas, different aspirations, and however well it may be to see what the thing is like, it takes no hold on your feelings, or even of your respect.” Galt was more easily impressed, writing back, “We were treated as if we were ambassadors and not as mere Colonists,” yet even he added warily, “it bodes no good no matter how flattering it may be.”

Three of the four returned home on June 17. Macdonald stayed a week longer to go up to Oxford for his honorary degree of Doctor of Civil Law. “This is the greatest honour they can confer, and is much sought after by the first men,” Macdonald reported in delight to his sister Louisa. He made it back to Canada early in July.

While little or nothing specific had been accomplished, things could hardly have gone better. Before the Canadians left, Cardwell gave Governor General Monck the green light to employ “every proper means of influence to carry into effect without delay the proposed confederation.” Above all, Confederation had been given de facto Royal Assent.

The Confederation project now resumed its forward motion, if still creakily. A shift in Maritime public opinion began. To help it along, Cardwell began to dangle before the Maritimers the possibility of improvements in the terms agreed to in the Quebec Resolutions. Those most attracted by this bait were the Maritime Roman Catholic bishops, who set out to secure guarantees for their separate schools.

On closer scrutiny, Confederation’s election defeat in New Brunswick turned out to be less crushing than it had first seemed. The Saint John Telegraph calculated that the vote had been 15,979 for the anti-Confederate Smith against 15,556 for Tilley. A key by-election was due that fall. To help New Brunswickers make the right judgment about what to do, Tilley wrote to Macdonald, estimating first that victory would require “an expenditure of 8 or ten thousand dollars,” and then asking, “Is there any chance of the friends in Canada providing half the expenditure?” On the back of this letter, Macdonald scribbled to Galt, “Read this. What about the monies?” Later, Charles Brydges of the Grand Trunk Railway reassured Macdonald that he had “sent the needful to Tilley” and had “kept all our names here off the document.” Down went Canadian money; in came the votes for the pro-Confederate candidate.*142 By the fall, New Brunswick’s Lieutenant-Governor Gordon was able to brag to London, “I am convinced I can make (or buy) a union majority in the Legislature.”

A new problem had arisen. On July 30 Étienne-Paschal Taché died, sending Macdonald his last poignant note: “J’aimerais à vous voir encore une fois avant le long voyage que je vais bientôt entreprendre.” The day after Taché’s funeral, Monck asked Macdonald, as the most senior of the quartet, to head the ministry. Brown, when called in to see Monck, would have none of it; while denying he had any “personal aspirations whatever,” he pointed out that his own Reformers were twice as numerous as Macdonald’s Conservatives. He and Macdonald then met one on one. They reached no meeting of minds, despite an offer by Macdonald to step down for Cartier. Given that those two were joined politically at the hip, Brown naturally rejected it. Eventually they reached a compromise: the new premier would be an anonymous, long-serving Canadien, Sir Narcisse-Fortunat Belleau. He was sworn in on August 7.

Then came another complication. Brown, always quick to identify a slight, had already complained that Macdonald had given Galt public precedence over him. He also harboured suspicions—justified, no doubt—that Macdonald and Cartier were dispensing patronage that ought to have been his to allocate. From that point on, Brown refused to speak to Macdonald, dealing only with Cartier.

The malaise continued. A mid-summer government statement on Confederation made to the legislature in August had nothing new to say. Macdonald himself was often absent, supposedly on doctor’s orders, but in fact because he was drinking heavily.

Yet while Macdonald was drinking far too much at the worst possible time, his antennae remained as alert as ever. In July a large conference was held in Detroit, organized by the Detroit Chamber of Commerce, to discuss and if possible reverse Washington’s decision to end the Reciprocity Treaty with Canada in the spring of 1866. No fewer than five hundred American businessmen attended, as well as fifty Canadians, all worried deeply by the impending loss of cross-border trade. During the meeting the American consul general in Montreal, J.R. Potter, chose to declare in his speech that the entire problem could be resolved by the United States annexing Canada. News of this extraordinary behaviour by the principal representative of the U.S. Government in Canada took time to reach Ottawa. Macdonald invented an occasion for himself to deliver a speech in Ottawa (press releases didn’t exist then), and on September 28 gave his reply in a way that revealed a great deal about his personal feelings on Canada’s future in North America. First he talked about Confederation, actually a bit optimistically: “The union of all the Provinces is a fixed fact.” Then he talked about himself: “The mere struggle for office and fight for position—the difference between the ‘outs’ and ‘ins’ have no charms for me,” he said, “but now I have something worth fighting for—and that is the junction of Her Majesty’s subjects in all British North America as one great nation.” Macdonald knew fully what his own leitmotif was.

As fully, Macdonald now knew precisely what he was doing for himself. The month before, in a letter to Monck on June 26, 1866, he described Confederation as “an event which will make us historical.” He then added, almost as if warning Brown to stay out of his way, “—not with my will would another person take my position in completing the scheme for which I have worked so earnestly.”

As was now inevitable, relations between Macdonald and Brown went from bad to worse. In November, Brown took umbrage at Galt’s having been sent alone to Washington to try (unsuccessfully) to negotiate an extension of the Reciprocity Treaty. Macdonald got Galt to explain that his mission had been unofficial and that, on a second trip, a Reform minister would accompany him.

A parting could no longer be prevented. On December 17 Brown sent in his resignation. Afterwards, he wrote to Anne, “Thank Providence—I am a free man once more.” Macdonald got Galt “without fail to prepare at once” an account of what had happened between him and Brown so he could show it to the other Reform ministers, in the hope that he could convince them to stay rather than leave with Brown. The tactic worked: there were no other defections from the Great Coalition, and a third Reformer took Brown’s place in the government.

The long, intensely personal duel between Brown and Macdonald had reached its end. The clash of personalities made their parting inevitable, as did the fact that their objectives were fundamentally at odds. Brown wanted a “mini-federation” within just the United Province of Canada, to separate the French and the English. He had exulted at the end of the Quebec Conference that French-Canadianism had been extinguished and was delighted when he heard in the spring of 1865 that New Brunswick’s pro-Confederation government had been defeated in the election. This result, he wrote to Anne, “is a very serious matter for the Maritime provinces, but magnificent for us.” Macdonald’s purpose, by contrast, was a transcontinental nation, with Confederation as its essential first building block, one based on a pact of trust between French and English. Brown’s last comments about Confederation before it actually happened, during a debate in the legislature in the summer of 1866, showed how distant he was from Macdonald. There, Brown condemned as “a most inconvenient and inexpedient device” any attempt to use the constitution “to bind down a majority…to protect a minority” rather, he argued, the majority should be left free “to act according to their sense of what is right and just.”

Nevertheless, Brown fully deserved McGee’s encomium to him for having displayed “moral courage” in bringing his followers with him into the Great Coalition government that would bring about Confederation. While many of his political views were narrow, Brown was an exceptional public figure. There was even an expansiveness to his later explanation for quitting: “I want to be free to write of men and things without control…. Party leadership and the conducting of a great journal do not harmonize.” Most certainly he deserved from Macdonald a great deal more than the crabbed, ungracious compliment he later paid him: “[Brown] deserves the credit of joining with me; he and his party gave me that assistance in Parliament that enabled us to carry confederation.”

From this point on, the tide began to turn decisively. Through the winter, New Brunswick’s Premier Smith and his government progressively lost their way. By the spring of 1866 he had been pushed back so far onto the defensive that the Throne Speech actually contained a description of Confederation as “an object much to be desired.” Not long afterwards, his government was defeated in the House and an election called. At that instant, there appeared exactly the political reinforcements that Macdonald most needed: the Fenians appeared on New Brunswick’s borders.

In fact, Canada-U.S. relations had improved considerably by this time, if for the worst of all possible reasons. The previous April, just one week after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House, President Lincoln had been assassinated while attending a play at Ford’s Theater in Washington. Unanimously, Canadian politicians and the press recognized that a giant had been struck down, and they mourned the loss to the United States as well as to the world. The day after, the Toronto Globe appeared with its front page bordered in black; Toronto sent two municipal representatives to attend the funeral, and during the two hours that the service was being held, church bells throughout the country pealed unceasingly while ships in the ports of British North America lowered their flags to half-mast. The most moving and the most deeply grieving services for Lincoln were those held in the small wooden churches of Canadian blacks.

At the same time, the rapid demobilization of the North’s armies provided relief from the threat of a possible invasion. Just one lingering cause for alarm remained: demobbed soldiers had been allowed to buy back their rifles for six dollars; noticeably, many of those doing so had been Irish Americans. Macdonald was kept well briefed about the Fenians’ doings by his intelligence chief, Gilbert McMicken. At least as much, he was kept well briefed by the Fenians themselves. They were talkative, boastful, combative (with each other) and, while brave soldiers individually, hopeless as an organized force. They did have one good marching song: “Many battles have been won / Along with the boys in blue / And we’ll go and capture Canada / For we’ve nothing else to do.”

As St. Patrick’s Day, March 17, 1866, approached, nervousness mounted in Canada. Some ten thousand militia men were mobilized. Nothing happened. Then on April 7, the streets of the Maine seaport of Portland were suddenly crowded with Irishmen, most carrying revolvers and with long knives in their belts; they went on to the town of Eastport to hold a “convention.” Their objective was the island of Campobello, New Brunswick. Two British warships hastily sailed from Halifax, followed by two troopships from Malta. Soon there was a mini Royal Navy fleet off the Maine coast, together with some five thousand British and New Brunswick militia soldiers. The Fenians straggled out of Eastport, leaving behind unpaid hotel bills and around fifteen hundred rifles. Actual action was limited to one boatload of Fenians who made it to an offshore Canadian island and burned down a customs warehouse.

That the Fenian raid had been a fiasco didn’t change its consequences but only multiplied them. Canada had been threatened. Britain had fulfilled its obligation to rush to its aid. Most disturbingly, American authorities had allowed the invasion to be attempted from its territory (no Fenian was ever charged afterwards for violating the neutrality laws). Everything that had happened reinforced the argument that Confederation was essential to national security.*143 Governor General Monck sent home the word that the militia’s performance had ended forever the accusation so often hurled at the North American colonies of “helplessness, inertness and dependence.” Indeed, the Fenian expedition had been so counterproductive that some people speculated that Macdonald had stage-managed the entire affair with McGee’s help.†144 Not a scrap of evidence suggests that was so. There was, though, something ominous. One of McMicken’s detectives reported he had been told that “one thousand dollars is offered in gold to anyone that will bring in D’Arcy McGee’s head.”

For the time being, Macdonald could not have asked for more than he already had. In Nova Scotia, Tupper was able finally to get the Legislative Assembly to approve a pro-Confederation resolution, which cleverly asked not for approval of Confederation but only for Nova Scotia delegates to take part in negotiations that could “effectually assure just provision for the rights and interests of Nova Scotia.”*145

A month later, Tilley won the New Brunswick election, winning even more decisively—33 seats to 8—than had his anti-Confederate opponent the previous year. One factor was the support of the Roman Catholic bishops. But money talked even more loudly than did the faith. In June Tilley had written to Macdonald, “Telegraph me in cipher saying what we can rely on…. It will require some $40,000 or $50,000 to do the work in all our counties.” A few days later, he wrote again, even more urgently, “To be frank with you, the election in this Province can be made certain if the means are used.” He suggested that the exchange of cash be made outside the province, in Portland, Maine. Monck then got into the act, telegraphing Macdonald: “I think it is very desirable that he [Galt] should undertake the journey to Portland.” In counterpoint, Galt wrote to Macdonald, saying, “That means had better be used—I think we must put it through,” adding that he would go to Portland together with Brydges in order to meet with Tilley and consummate the exchange. The use of the “means” did achieve its end. This exercise, undertaken for the higher cause of Confederation and one fully approved by a governor general of the highest probity, introduced Macdonald to the art of extracting election campaign funds from a large railway company.†146

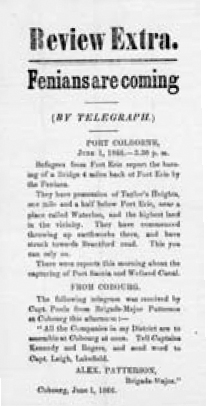

The Fenians had not yet completed their contribution to Confederation. On June 1, one of McMicken’s detectives sent an urgent telegram from Welland: “1,500 Fenians landed at Fort Erie.” Inaccurate in some details, it was correct in substance. About half that number of Fenians, many wearing Union or Confederate uniforms, had been ferried across the Niagara River led by a capable officer, John O’Neill. Canadian authorities, made complacent by the earlier fiascos, were slow to respond. O’Neill’s men occupied Fort Erie and cut the telegraph wires. A clash with the Canadian militia took place at the village of Ridgeway, in Welland County. The ill-trained militia were overwhelmed, suffering nine killed and thirty-eight wounded. Another clash with militia units outside Fort Erie ended in a second victory for O’Neill’s Fenians. None of the promised reinforcements from the United States arrived, though, so O’Neill ferried his troops back across the Niagara River. The U.S. authorities persuaded them to “abandon [their] expedition against Canada” in exchange for free transportation to their homes. The Globe proclaimed, “The autonomy of British America, its independence of all control save that to which its people willingly submit, is cemented by the blood shed in the battle.” To intensify Canadians’ anger, and to magnify their sense of aggrieved nationalism, three of the militia men killed had been teenaged students from the University of Toronto. Never again would Macdonald treat a threat of Fenian invasion as probable comedy.

The Fenians decisively helped Confederation. As American Irish trying to end British rule in Ireland, they invaded Canada—and so reminded Canadians of the threat to them from the south.

With approval now from both New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, with Canadians having just shown they were ready to fight for their country and, far from least, with the Imperial government having committed itself to guarantee five million pounds in loans for the Intercolonial Railway, Confederation stretched out ahead like a broad, flat highway.

A bump soon appeared. In London, the government of Lord John Russell went down to defeat on its key Reform Bill. The new prime minister, Lord Derby, would have to replace Cardwell, by now an authority on the Confederation file. The new colonial secretary was announced as Lord Carnarvon, just thirty-six years old, but, as was unusual, happy to have the post because he was a strong believer in the Empire. Carnarvon moved quickly. By July 21 a complete British North America Bill had been drafted in London, and it merely awaited the arrival of the Canadian and Maritime delegates to agree on its details before the document would be submitted to the Westminster Parliament.*147

Then came another bump, and a considerably larger one. The Maritimers arrived in London as planned, at the end of July 1866, but neither Macdonald nor any Canadians appeared.

One of the lesser mysteries of the Confederation chronicle resides in Macdonald’s failure to exploit the momentum built up by the middle of 1866 to rush a British North America Act through the British Parliament by that fall. There were some technical considerations. The constitutions for the soon-to-be created provinces of Quebec and Ontario had yet to be approved by the Canadian legislature. Also, Macdonald was convinced that the government needed first to lower Canadian tariffs to ease Maritime fears about high taxation before the climactic negotiations began. The new Derby government was weak, though, and the longer the delay, the greater the risk that the political crisis absorbing the British Parliament would halt Confederation’s progress and give its critics a chance to regroup.

Macdonald remained gripped in his inertia. He ignored a June 17 warning from Tupper reminding him that an election in Nova Scotia—of which the outcome was far from certain—had by law to be held before May of the next year, 1867. Tupper pleaded, “We must obtain action during the present session of the Imperial Parliament or all may be lost.” Governor General Monck was at least as anxious. To get Macdonald moving, he sent him a stinging letter on June 21. In it, he bluntly told Macdonald that “valuable time is being lost and a great opportunity in the temper and disposition of the House is being thrown away by the adoption of this system of delay.” Monck then showed the mailed fist inside his habitually well-padded glove: “I have come to the delicate conviction that if from my cause this session of Parliament should be allowed to pass without the completion of our portion of the Union scheme…that my sense of duty to the people of Canada myself would leave me no alternative except to apply for my immediate recall.” A bit disingenuously, he added that he wasn’t mentioning his possible resignation “by way of threat.”

Macdonald’s reply, one day later, began by saying that Monck’s letter had “distressed” him greatly. Thereafter, he conceded nothing. “The proceedings have arrived at the stage that success is certain and it is now not a question of strategy. It is merely one of tactic,” he wrote. This tactic involved picking “the proper moment for projecting the local scheme [the provincial constitutions].” Macdonald then showed his own mailed fist: “With respect to the best mode of guiding the measure through the House, I think I must ask Your Excellency to leave somewhat to my Canadian Parliamentary experience.” The fist having been shown, Macdonald offered a conciliatory hand: Monck must not resign because “to you belongs…all the kudos and all the position (not to be lightly thrown away) which must result from being a founder of a nation.” After that delicate reminder of the relationship between Monck’s prospects for future Imperial employment and the achievement of Confederation, Macdonald ended jauntily, as he so often did, “My lame finger makes me write rather indistinctly. I hope you can read this note.”

Governor General Monck. He and Macdonald had their disagreements, but they worked well together, making sure that Tilley had enough money to win the key election in New Brunswick for Confederation.

Monck’s reply, written the day he received Macdonald’s letter, was almost as deft. While he accepted without question “your right as a leader of the Government to take your own line,” he nevertheless reserved the right to advise Mac donald against “a course of conduct which I consider injudicious.” He retained his right to resign should Macdonald continue to “hang back now when all other parties to the matter are prepared to move on.” Thereafter, Macdonald moved no faster than before, but some of the tensions each felt had been released. And their relationship remained as cordial as ever, even surviving Macdonald’s spectacular misdemeanour of so losing control during one visit to the governor general’s residence as to vomit over a newly upholstered chair Lady Monck had installed in her drawing room.*148

A major cause of Macdonald’s shilly-shallying was the most obvious. He was drinking more heavily, more continually than he had ever done before, at times having to grip his desk so he could remain standing in the House. Tiredness and stress made him vulnerable. So did D’Arcy McGee. Night after night they caroused together at Ottawa’s Russell Hotel. After one such binge, while Macdonald managed to make it back to his room, McGee wandered off into the night and was found the next morning curled up on the desk of the editor of the Ottawa Citizen. Cabinet finally addressed the matter, one minister calling the behaviour of the pair a “disgrace.” In response, Macdonald sought out McGee and informed him, “Look here McGee, this Cabinet can’t afford two drunkards, and I’m not quitting.”

Both continued to drink heavily. On August 6, Brown, now an ordinary member, reported to Anne that “John A. was drunk on Friday and Saturday, and unable to attend the House. Is it not disgraceful?” The Globe went into attack mode: Macdonald had not been sober for ten successive days and was unfit for his duties as minister of militia. In fact, it was not until the legislature had adjourned in September that he began to regain control over his drinking. He was able to handle a mini-crisis caused by Galt’s resignation from the cabinet after he failed to win his long-sought guarantees for Protestant education in Quebec. After shuffling the ministry, Macdonald still persuaded Galt to come to London as one of Canada’s constitutional delegates. In the meantime, though, McGee in particular continued to drink heavily.

That Confederation was now so close yet still remained vulnerable was undoubtedly a major cause of Macdonald’s prolonged drinking. But cool calculation may also have influenced his behaviour. As people kept blaming Macdonald for his misdeeds, they paid less attention to the fact that time was indeed slipping steadily by. And that is precisely what Macdonald wanted to happen.*149 His objective was to shrink to a bare minimum the span of time between the moment when the Confederation delegates finally agreed on a revised constitution and the actual introduction of the document into the British Parliament. The longer the gap between those two events, the greater the risk that Confederation critics would learn of any last-minute changes to the original Quebec Resolutions and demand a reopening of the entire debate on the grounds that Canada’s Legislative Assembly had approved a different version of Confederation.†150Macdonald explained his stratagem to Tilley in a letter on October 6: “The Bill should not be finally settled until just before the meeting of the British Parliament” the measure had to be “carried per saltum—with a rush. No echo of it must reverberate through the British provinces until it becomes law.” Premature disclosure could “excite new and fierce agitation on this side of the Atlantic.” But, he promised, “the Act once passed and beyond remede, the people will soon be reconciled to it.”

Not until the end of November 1866 did the Canadians finally make it to London. They—Macdonald, Cartier, Galt, Hector-Louis Langevin (a rising Quebec bleu) and two Reform ministers, William McDougall and William Howland—all stayed at the now-familiar Westminster Palace Hotel, looking out on Westminster Abbey and with the Houses of Parliament across the road.*151 Already ensconced there were the two five-member Maritime delegations, headed by Tupper and Tilley. In getting them to join this final, climactic phase of a project that by now had been going on for more than two years, Macdonald and the Fenians had played critical roles. For the Maritimes, though, the decisive force had been that of Britain—far less by its “turn[ing] of the screw” than by the irresistible pull of loyalty. In the end, what caused Maritimers to come in was their realization that in order to remain British, they had to become Canadians.