MAUD BUTLER FALKNER, MATRIARCH OF THE FALKNER FAMILY and my beloved grandmother, was one of those people I thought were just born old. She was sixty-four when I came along. Recently the Oxford Eagle ran a picture of her taken by an unidentified photographer in the mid-1890s. There she sits in all her lace and ruffles, puffed sleeves falling below her elbows, a wide sash at her corseted waist, upswept hair, a small, delicate, lovely, dark-eyed figure with a childlike countenance, slightly sad, innocent and shy, and very, very young.

This is not the woman I thought I knew. Growing up I became aware of her private nature, of the distance she kept between herself and the rest of the world—and her family—but I had no idea of the extent to which she had isolated herself. For instance, we never celebrated her birthday because no one knew the date. Though I had always understood that I was named for my father, I did not know until I was a grown woman, long after Maud’s death, that my father had been named for his maternal grandmother, Lelia Dean Swift Butler.

The day that Maud married Murry Falkner in the fall of 1896 in Oxford, Mississippi, she gave up being a Butler and became a Falkner. It was as if she wished to eradicate everything pertaining to the Butlers, or so I’ve been told. Yet there are a few family members and Faulkner biographers who credit the Butlers for the genius of William Faulkner.

I did not know that Maud’s mother and brother were buried in St. Peter’s Cemetery within a stone’s throw of all the old Falkners (and now of Maud herself). I was not aware that she had a brother or that they grew up in Oxford. The house where she spent her childhood still stands on what is now Jefferson Avenue. A Victorian cottage with a touch of gingerbread surrounding the porch, of light brown clapboard construction with heavy oak double doors and a backyard large enough to hold her father’s pigs, cow, and mule, it is situated a few blocks northeast of the square within shouting distance of the L. Q. C. Lamar house. The Butler and Lamar children were playmates. I like to think of her as a happy little girl sitting in the front porch swing, waiting for her father to come home for supper.

Maud’s family arrived in Oxford long before the Falkners. According to Joel Williamson’s William Faulkner and Southern History, Charles G. Butler and his wife, Burlina, Maud’s grandparents, were living in Oxford in the early 1830s while the Falkners were still in Ripley, Mississippi. They were among the earliest settlers in Lafayette County. Charles G., an influential Baptist and prosperous property owner, was the first county sheriff and surveyor. He laid out the grid for the new city of Oxford. He and Burlina owned twenty-five acres of land, including lots on the courthouse square where, in 1840, they built a hotel named the Oxford Inn that “became the centerpiece of the Butler family’s prosperity.”

I had no idea, growing up, that my Butler great-great-grandparents owned more property in Oxford than the Falkners. Their real estate holdings approached $12,000, “placing them comfortably among the well-to-do people in the county.” There were six children in the family. The youngest son, Charles Edward, was to be Maud’s father. They called him “Charlie.” I never heard his name mentioned.

After Charles G. died in 1855, Burlina, “a woman of impressive managerial skills,” was able to double her husband’s real estate holdings. A successful businesswoman and a “slaveholder of significant proportions,” she, along with her sons William and Henry, owned real estate holdings worth some $95,000, nearly twice that of the Falkner fortune.

Then the Butlers fell on hard times. During the war, General A. G. “Whiskey” Smith burned Oxford to the ground. Burlina, according to Williamson, “escaped from her burning hotel with nothing more than the clothes on her back.” Until then, the Butlers and Falkners had led parallel lives, comfortable and financially secure. They also shared a penchant for violence, which was a source of pride for the Falkners, shame for the Butlers.

Very little is known about any Faulkner ancestors before the “Old Colonel,” William Clark Falkner, for whom William was named. He was larger than life with an extraordinary career: lawyer; veteran of two wars, Mexican and Civil; owner of extensive land holdings in Ripley, Mississippi; builder of the first railroad in north Mississippi; and published writer, best known for The White Rose of Memphis and Rapid Ramblings in Europe. He served as the prototype for several of William’s aristocratic characters, such as Colonel John Sartoris and Major de Spain. In many ways William emulated his great-grandfather by living as a gentleman farmer with horses and dogs on an antebellum estate, and by writing, of course.

The Old Colonel was the most violent of the Falkners. It was generally known in north Mississippi that his “Bowie knife and pistols [were] consistently about his person.” In May 1849, one Robert Hindman made the fatal mistake of calling Falkner “a damned liar,” then pointing a revolver at him. As the two men struggled for the pistol, it misfired three times. Falkner drew his knife and stabbed Hindman through the heart, killing him instantly. The inscription on Hindman’s original tombstone read “Murdered at Ripley, Miss. By Wm. C. Falkner May 8, 1849.” The Old Colonel was tried and acquitted. “Murdered” was changed to “killed.”

Two years later, the Old Colonel shot and killed a friend of the Hindman family, Erasmus W. Morris. Again, an argument had led to violence. Falkner pulled his pistol and fired at Morris’s head, killing him instantly. Once again he was tried for murder and acquitted.

Then Colonel Falkner and Thomas Hindman, Jr., the brother of the murdered—or killed—Robert Hindman, drew up an agreement to fight a duel in Arkansas, where it would be easier for the survivor to avoid prosecution. The agreement read: “Each man is to have two revolvers, take stands fifty yards apart, and advance and fire as he pleases” (italics mine), which is the strangest dueling procedure I’ve ever heard of. Fortunately, a mutual friend intervened and the duel never took place.

On November 5, 1889, Colonel Falkner was shot dead on the public square in Ripley by his former business partner, Richard Thurmond. The two had run against each other for a seat in the state legislature, which Falkner won by a landslide. Presumably embittered by the loss, Thurmond came looking for Falkner. The local newspaper reported that “Thurmond used a .44 caliber pistol to do the work.” Thurmond was indicted for manslaughter and was released on his own recognizance after he posted a $10,000 bail. His trial was postponed for a year. When the jury came in after a short deliberation, the verdict was “Not guilty.” Guilty verdicts were obviously hard to come by in those days.

A statue of the Old Colonel, which he himself commissioned in Italian marble at a cost of $2,022 (paid for by his heirs), stands today in the Ripley cemetery—in Williamson’s words: “Eight feet in height and one quarter larger than life. It rests atop a fourteen foot pedestal.… The right forearm thrusts forward from the elbow, hand open, palm up” as though “explaining earnestly, patiently, things that can be made clear to thoughtful persons.”

When I was a girl and a not-so-thoughtful person, I organized a midnight ride to Ripley to offer my respects to the Old Colonel. All was quiet in the cemetery. The moonlight was bright enough for us to read the inscription on the tombstone.

COL. WILLIAM FALKNER

BORN

JULY 6, 1825

DIED

NOV. 6, 1889

It took a few moments and a little help from my friends for me to climb his statue. They handed me a cold Budweiser already opened. I carefully placed it in his palm.

The violent streak passed over the next generation only to be inherited by Murry Falkner, the Old Colonel’s grandson and William’s father. According to Williamson, Murry “in an overly aggressive attempt to defend the honor” of a young woman (not Maud) “got into a fight with a local man with a dangerous reputation.” Murry won the fight, but the next day the man found him in a drugstore on the square and shot Murry “from behind with a twelve-gauge shotgun.… Then, while Murry lay on the floor, pointed a pistol at his face and shot him in the mouth.” His mother, Sallie Murry Falkner, rushed to the scene as soon as she heard about the shooting. She used asafetida to induce vomiting. Murry threw up the bullet, the story goes, and his life was saved. A miracle.

Growing up I heard about Falkners good and bad, but the Butlers were seldom mentioned. I knew, for instance, that my father’s generation called the Young Colonel and his wife “Grandfather and Grandmother Falkner.” Murry was referred to as “Big Dad.” My cousins Jimmy and Chooky called their uncle William “Brother Will,” though my cousin Jill and stepcousins Cho Cho, Malcolm, and Vicki—and I, of course—called him “Pappy.” Maud was “Sis Maud” to her in-laws, “Granny” to Vicki and Jill, and “Nannie” to Jimmy, Chooky, and me. This confusing array of nicknames demonstrates once again the Falkner propensity for failing to agree about almost anything. And yet only one such name survived in the Butler family: “Damuddy” was her grandchildren’s pet name for Lelia Dean Swift Butler, Maud’s mother.

There were, as I was to discover, reasons for this omission.

Charlie Butler—Maud’s father—and Murry’s father, John Wesley Thompson Falkner, were contemporaries, both born in 1848. In 1885, J.W.T. moved his family to Oxford, set up a law practice, and later became the founding president of the First National Bank. At the same time, the war and its aftermath had taken a serious toll on the Butlers. Before he was twenty, Charlie became head of the family. His father and two older brothers were dead. On July 31, 1868, Charlie and Lelia Dean Swift applied for a marriage license in Lafayette County. They were married on August 2.

Little is known about Lelia Dean Swift. It was said that she came to Oxford from Arkansas, that she had studied sculpture and painting, that she was a staunch Southern Baptist, and that she had been offered a scholarship to study art in Italy, which she declined because by that time she had two children: Sherwood, born in 1869, and Maud, born in 1871.

Maud rarely spoke of her mother, but when she did it was with admiration for her talent. All of Oxford, it seemed, knew of Lelia’s ability to carve a pound of butter into a swan, or chisel dolls from blocks of ice. She was considered an intelligent, talented woman, yet, as far as I know, only one of her paintings survives.

In 1875, Charlie Butler had to borrow money to support his family, but the next year his circumstances improved vastly. He was appointed town marshal by the mayor and board of aldermen, a position he would hold for nearly twelve years. According to Williamson, as town policeman, a job similar to that of his father, Oxford’s first sheriff, Charlie’s duties included the arrest of “anyone drunk or committing a nuisance, or exhibiting a deadly weapon or using profane or obscene language or acting disorderly or violating any ordinance of this town.”

In addition to keeping the peace, Williamson continues, Charlie served as tax collector. His salary was $50 a month and 5 percent of all taxes collected. In 1876, city taxes totaled $3,000 and Charlie earned $150, a sum that quadrupled over the next few years as Oxford grew. Charlie was also responsible for enforcing quarantines during epidemics, for “disinfecting privies with lime, and the never-ending, exasperating chore of rounding up livestock that had escaped into the streets. He was paid 50 cents for catching a pig, 25 cents for keeping it, 25 cents for removing a dead dog.”

Charlie filled an office later called “town manager,” and with it his duties grew. His “place in the Oxford community seemed very secure.… He was seen as an energetic and engaging young man … who moved about town doing its business effectively and efficiently.” He joined the Masonic Order in 1878.

Charlie’s downfall started in 1881, when he came up $2,000 short in reported tax revenues. The board of aldermen showed leniency, however, and allowed him sizable deductions for expenses. He ended up paying the city $138.05.

The next problem was far more serious. On May 17, 1883, the Oxford Eagle reported that Charlie had killed Sam Thompson, the editor of the newspaper. On the day of the shooting, court was in session and Charlie was acting as bailiff. It was his job to summon defendants to court. He called for a man named Sullivan. At that moment Sam Thompson, also waiting to be summoned, was slumped on a bench outside the courthouse, very drunk. Each time Charlie called Sullivan’s name, Thompson answered, “Here!” Then he staggered about, pretending to be the bailiff, calling his own name.

Thompson was facing trial “for abduction of a female and unlawful cohabitation.” This was no news to Oxford. Everyone knew that Thompson was keeping a teenage mistress, Eudora Watkins. She lived with an African American woman who worked in Thompson’s household and, according to rumor, served “sexual purposes.” Eudora herself was under indictment for carrying a deadly weapon.

When Sullivan passed Thompson on his way into court, Thompson cursed him, “applying to him … a very gross epithet.” Charlie attempted to arrest Thompson, who at first went peaceably. Then he refused to go any farther. In the ensuing scuffle, Thompson grabbed Charlie’s “coat sleeve, lapel or throat,” and Charlie shouted for help. A man appeared within seconds; everyone inside the courthouse heard the shouting and commotion. The three men became locked in a deadly embrace. Charlie drew his revolver and said, “Thompson, if you don’t let me go, I’ll kill you.” Then he lowered the gun and pointed it at the ground and repeated, “Turn me loose or I will kill you.”

“Shoot, you barn-burning son of a bitch!” Thompson yelled. And so Charlie did. Thompson was dead, a bullet through his heart. Charlie surrendered, was indicted for manslaughter, and released on $2,500 bail pending the next court session. No one knows why Thompson accused Charlie of arson. As Williamson writes, barn burning, “the crime of sneaks and cowards,” was not one of Charlie’s failings. At his trial in May 1884, Charlie Butler was found not guilty of manslaughter, the consensus being that “if there was any man who needed killing in Lafayette County … it was Sam Thompson.”

Throughout the next year Charlie continued to serve as marshal and tax collector. Since taxes had been raised to support a new school, a considerable amount of money was flowing through his hands. Then the board of aldermen hired attorney J. W. T. Falkner to audit the books. He found a great deal of tax revenue missing. No one knew exactly how much, since Charlie had been keeping the accounts. Before Christmas 1887, Charlie Butler disappeared. He took his leave on a westbound train with an estimated three to five thousand dollars in embezzled city tax revenues and a beautiful octoroon, a seamstress in the Jacob Thompson household. Jacob Thompson was a prominent lawyer and politician who served as secretary of the Interior from 1857 to 1861. They vanished without a trace, never to be seen or heard from again—or so the Falkner version of the story goes.

Four inches of snow fell on Lafayette County that December. Oxford must have looked like a Christmas card. I ache for Maud, who turned sixteen that November. She never (in my lifetime) put up a Christmas tree, no red and green candles in the dining room, no wreath on the front door. There was no Christmas celebration for Maud in 1887 or thereafter. I had always thought Dean’s death caused her to ignore the holiday. Now I know better.

I’ve learned much more about Charlie’s disappearance thanks to a newly discovered cousin, Carolyn Butler Cherry. We share Charlie, for better or for worse, as a great-grandfather: Charlie’s son, Sherwood, was Carolyn’s grandfather; Charlie’s daughter, Maud, was my grandmother. (Charlie was William Faulkner’s grandfather.) I was raised in the Faulkner family, where Charlie’s infamous departure was never discussed. Carolyn grew up in the Butler family, where the consensus was that Charlie had no intention of abandoning his wife and children, was planning to come back home someday, and was possibly killed by a prisoner he was transporting.

The source of this information, previously unpublished and appearing here for the first time with Carolyn’s permission, is a letter passed down in the Butler family. It is handwritten by Charlie and dated November 19, 1887:

My Dear Lelia,

I did not stop in either St Louis or Kansas. I was up all night last night & feel real well this morning. I will only be here a few minutes, so I will have to make this short—but I will write you a long letter as soon as I stop. I never saw any body that I even know before I left—Cairo. I wanted to stop and see Barry Glick in Kansas City but did not stop will see when I come back through there. Much love and kisses for your self and children.

Lovingly,

Charlie

According to Carolyn, the Butler family has long believed that Charlie, acting as a deputy sheriff, was in the process of transporting a prisoner from Topeka, Kansas, to Holly Springs, Mississippi. He and the unnamed prisoner disappeared and were never heard from again. Sometime after the disappearance in November 1887, Lelia Butler received an envelope marked “United States Senate/Official or Department Business/FREE” postage. It was addressed to Mrs. L. D. Butler of Oxford, Mississippi. The envelope contained an unused ticket, number D437, on the Kansas City, Memphis and Birmingham Railroad. The ticket was issued in Memphis on November 13, 1887. The passenger is identified as “Charles Butler + one.” It was good from Memphis to Holly Springs. The account listed was I.C.R.R. and it was good for one trip only, until November 31 [sic], 1887. This reservation for two seats was sent to her apparently because it had been paid for in advance but had not been used.

Another document that was passed down in the Butler family is a telegram dated “December 188?” from Topeka, Kansas, addressed to “G. T. O’Haver Supt of Police Mps.” The message reads simply “No such warrant applied for.” It is signed “E. B. Allen, Secy State.”

A month after Charlie disappeared, Lelia must have contacted authorities to investigate whether he was indeed assigned to bring back a prisoner from Kansas. The Memphis superintendent of police, G. T. O’Haver, contacted Topeka on her behalf, and this telegram indicates that no prisoner transfer warrant was applied for, by Charlie or anyone else.

It is possible that Charlie told Lelia that he was going to Topeka to escort a prisoner back to Mississippi. The letter does not mention his mission, which implies that Lelia might have known why he was in Topeka.

Carolyn observed that “the tone of the letter does not appear to be from a man who was about to disappear, leaving a wife and two children.” I agree, but if there was no warrant or prisoner, Charlie’s letter becomes suspect. Why was he in Topeka? At best, the letter seems to be a poignant farewell to his wife and children. One senses the desperation of a man on the run, missing his family and racked by guilt, yet at the same time trying to cover his tracks and provide a plausible explanation for his disappearance. The promised follow-up letter (“a long letter as soon as I stop”) never arrived.

With his experience in law enforcement, Charlie would have known that reserving a train ticket for two was routine planning for transporting a prisoner. At a stopover in Memphis, before boarding the train to Kansas (via Cairo, Illinois) he reserved two return tickets from Memphis to Holly Springs for “Charlie Butler + one.” Two days later he posted a letter from Topeka and disappeared forever.

Carolyn grew up believing that the prisoner Charlie allegedly was transporting from Topeka robbed and killed him. She accepted that his letter to Lelia was sincere and that he intended to return to Oxford and take his punishment. She grew up hoping for the best, whereas I grew up knowing nothing about the Butlers.

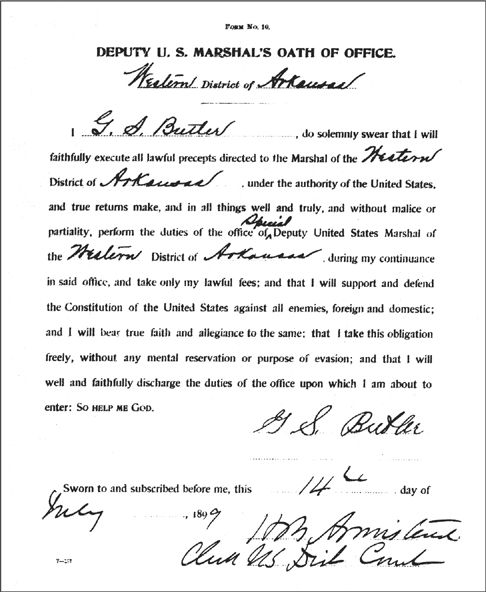

However, I now believe Charles E. Butler may have surfaced in Fort Smith, Arkansas. In 1899, a “G. S. Butler” was sworn in as a U.S. deputy marshal at Fort Smith. Was this Charles E. Butler’s alias? Charles may have substituted his father’s and son’s initials for his own. His father’s middle initial was G and his son was named Sherwood.

It is logical that Charlie would have returned to law enforcement. If so, Fort Smith was the place to do it. The Federal Court for the Western District of Arkansas was based there. Judge Isaac C. Parker, known as the “hanging judge,” presided over the court, which had jurisdiction over the Indian territories and many lawmen on its payroll.

It is intriguing that the deputy marshal’s oath of office signed “G. S. Butler” contains a signature similar to Charlie’s handwriting. He had a distinctive way of writing a capital B with a loop before it. This loop can be seen in both the G. S. Butler signature and the name “Barry” in line eleven of Charlie’s November 19 letter to his wife.

G. S. Butler was a man of mystery who left behind no personal data, no birth or burial records. He is not listed on any census in Fort Smith, Arkansas, or the surrounding counties. Who was he? Was he Charles E. Butler?

When Charlie left Oxford with the town’s tax receipts, a seamstress in the household of Jacob Thompson disappeared at the same time. It was said that they ran away together. The 1880 census listed two mulatto servants in the Thompson household, Laura Poindexter, twenty-five, born in Kentucky in 1855, and her daughter, Lou, six, born in Tennessee in 1874. At the time of the census, Jacob Thompson lived in Memphis, but he had retired by 1887 and had a home in Oxford when Laura ran away (presumably taking her daughter with her). It is possible that Laura Poindexter was the “beautiful octoroon” who disappeared with Charlie Butler. We will probably never know.

The situation is as complicated as a William Faulkner short story: After Maud’s father ran away with tax receipts, her future father-in-law, J. W. T. Falkner, in his capacity as city attorney, prosecuted Charlie Butler in absentia. Obviously, Maud and Murry were so much in love that they did not allow the tensions between their parents to affect them. Almost to the day nine years later they were married, and from then on neither her father’s crime nor his name was discussed by the Falkners.* William would not have learned about his Butler grandfather at home. Perhaps one of his schoolmates said, one day at recess, “Hey, Bill, I hear your granddaddy ran off with the town’s money.”

In January 1888, Charlie was voted out of office, in absentia, at a special meeting of the board of aldermen held “for the purpose of hearing report of committee to audit Books of C.E. Butler, absconding marshall.”

At the time of Charlie’s flight, Lelia was thirty-eight years old. Their marriage had been above reproach. Charlie was considered an earnest, hardworking provider. Although Lelia herself remained a mystery, refusing to discuss her past with anyone, the couple was well connected socially. The problem, as Joel Williamson diplomatically observes, was that Charlie and Lelia “did not get along.” Lelia did not have any more children after Sherwood and Maud. The absence of doctors’ records of miscarriages or stillbirths would suggest that after Maud’s birth there was little or no sexual relationship between Lelia and Charlie.

Charlie did not leave his family penniless. The house was in Lelia’s name, and in 1889, the 148 acres that Charlie had inherited from his parents were auctioned off on the courthouse steps. Meanwhile, Maud attended the Industrial Institute and College for the Education of White Girls in Columbus, Mississippi. In 1890, she and Lelia were living in Texarkana, Arkansas, where Maud worked as a secretary. She and her mother visited Sherwood often in Oxford. Maud renewed friendships with her childhood friends, among them Holland Falkner and her brother Murry.

Murry and Maud were married in the Methodist parsonage on November 8, 1896, quietly, without any family members present. They left for their new home in New Albany, Mississippi, the next morning. Lelia did not attend the ceremony because of her hard feelings toward Murry’s father. For years afterward, whenever she wrote to her daughter, the letters were addressed:

Miss Maud Butler

in care of

Mr. Murry Falkner

No wonder Maud never talked about her family.

Lelia died leaving little tangible evidence of her existence, no letters or books, no pieces of jewelry or furniture. I have one painting, fourteen-by-twenty-two-inch, oil on canvas, of three ears of Indian corn with large husks, tied together against an azure background. The painting has no date. The signature is in white block letters in the lower right-hand corner: “Lelia Dean Butler.” The painting is so old and dry that the oils have flaked off, leaving splotches of bare canvas. I found it rolled up on the top shelf of a linen closet when I moved into my grandmother’s house in 1970. Now it hangs in our living room in an ornate antique gilt frame.

Above Lelia’s Indian Corn hangs a painting by Maud, an oil on canvas approximately the same size, unframed. It is a near-life-size portrait of a beautiful copper-skinned African American girl, just the head and shoulders, dressed in green with a small green cap on her close-cropped black hair, a gaudy red and green drape behind her. Her large black eyes stare solemnly out at you. The painting is signed in the lower left-hand corner “MFalkner,” Maud’s standard signature. Printed on the back of the canvas in her distinctive hand is the title, Dulcie. The portrait is undated but I know that Dulcie modeled for Maud’s art class at Oxford’s Mary Buie Museum in the 1940s. I also know that Maud would never have displayed Dulcie in the living room or anywhere else.

When I asked my grandmother to help me join the DAR—having failed miserably as a Girl Scout I thought I might fare better as a Daughter of the American Revolution—she made her attitude toward her ancestors quite clear. “Lamb,” she said, “I don’t know whether my ancestors were hanging by their heads or their tails and I don’t intend to find out. Not even for you.”

*In the summer of 2008 I asked my father’s cousin Dot Falkner Dodson, Murry’s niece, what she had heard about Charlie. She was shocked that I would bring up the subject and was cautious and politic in her reply. She said that she’d always wondered if I “knew about it.” Charlie’s disappearance was still a taboo subject among the Falkners, more than a century after the fact!