‘The art of war is simple enough. Find out where your enemy is. Get at him as soon as you can. Strike him as hard as you can, and keep moving on’

General Ulysses S. Grant

Two months after returning from the Scheldt, Campbell was transferred back to the 2nd Battalion, which had been stationed on Gibraltar since 2 July 1809. While Campbell had served under Moore and Chatham, the 2/9th had been fighting in Portugal under Wellesley (recently ennobled as Viscount Wellington) and was now on the Rock for rest and recuperation. Lieutenant Campbell was placed in the light company, the regiment’s skirmishers, as No. 2 to Lieutenant William Seward.* Born in Southampton, a few miles from Campbell’s school in Gosport, Seward was three months older than Campbell, had been gazetted ensign only two months before him and shared his lack of money. The light company operated as the battalion’s very own miniature light infantry corps. Its officers often had to fight hand-to-hand, so Campbell procured a short, lightweight, non-regulation version of the 1796 light cavalry sabre, probably from one of the numerous post-battle auctions of dead men’s chattels. In contrast to the swords carried by most infantry subalterns, this was a serious practical weapon, a favourite among officers who saw close action. Campbell carried it for the rest of his life.**

The light company guaranteed Campbell a place in the thick of any fighting; the ideal place for a young, ambitious young officer to get noticed or killed. He hadn’t long to wait. Marshal Soult was known to want Tarifa, the small port just along the coast at the southernmost tip of Spain. Though of no strategic significance, it would cock a snook at British domination of the straits if the French stormed Tarifa unopposed, and so Campbell’s company, as part of a mixed detachment of 360 men, was sent as a new garrison.

The French escaping Vitoria from A. Forbes’s Battles of the Nineteenth Century.

Six days after their arrival on 14 April 1810, Tarifa was surrounded by 500 French soldiers on a cattle-rustling mission. A spirited sortie drove them back into the countryside. Worried the enemy might return, the Governor of Gibraltar despatched an extra four companies of the 47th Foot to beef up the garrison. This did the trick. Soult seemed content to leave Tarifa to the British; if this bagatelle tied up Wellington’s troops, so much the better. After an uneventful summer, on 15 September Campbell’s light company was relieved by the 28th Foot and returned to Gibraltar.

Soult had bigger game in his sights. The Supreme Junta of Spain, driven by the French from Madrid during Moore’s foray into Spain, had decamped to Cadiz. Soult wanted this rebel outpost eradicated. He gave Marshal Claude-Victor Perrin 19,000 men (including engineers and artillery) to bring Cadiz to heel. By February 1810, Victor’s troops had encircled the town. Rather than waste lives in an armed assault, Victor was content to bottle up the Spanish on their isthmus and starve them out.

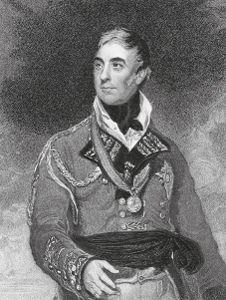

As soon as the French appeared, Wellington started reinforcing Cadiz with British troops under the command of Major-General Thomas Graham, a soldier of proven courage and personal resource. For him, fighting the French was also a matter of personal vengeance. His wife had died in France at the outbreak of the revolution and Graham had been moving her remains when rampaging Jacobins ripped open the coffin, convinced that it was being used to smuggle weapons.1 Graham never forgave this desecration.

For nearly a year he waited in Cadiz. Then in January 1811, a ‘favourable opportunity for acting offensively’ presented itself, Victor’s army ‘having been diminished by a detachment of four or five thousand men’.2 Graham had a bold scheme to raise the siege: while Victor’s gaze was on Cadiz, Graham would sail south, land near Gibraltar and, in concert with the Spanish army, march back and attack the French troops in the rear while the garrison left at Cadiz simultaneously stormed out and rushed the enemy lines. It was risky. Cadiz would be left vulnerable and the French general Sebastiani had enough men in Marbella to make trouble for Graham.

Graham’s men left Cadiz on 21 February 1811 and landed at Algeciras the next day. Here they met up with a detachment from Gibraltar made up of the flank companies of the 2/9th, 82nd and 28th Foot, including Seward and Campbell’s light company. These six companies would form a crack flank battalion, led by Campbell’s old Tarifa garrison commander, Major ‘Mad John’ Browne (made brevet lieutenant-colonel for the campaign), and subject to Graham’s direct orders only. Graham now fielded 5,000 men.

Thomas Graham (1748–1843). Steel engraving by H. Meyer, after T. Lawrence. (Courtesy of www.antique-prints.de)

On the 27th a Spanish contingent of 7,000 soldiers arrived. Inexperienced, poorly equipped, dressed in a ragbag of uniforms and vapidly led by mediocre officers, they nevertheless comprised the bulk of the allied army, so supreme command now passed to Spanish general Manuel Lapena. History has little good to say about Lapena, a man who, in Blakeney’s words, mistook ‘mulish obstinacy for unshaken determination’.3 Others have been less charitable. Anthony Brett-James described him as a ‘plausible, incompetent man, whose selfishness and disloyalty were matched by his dislike of taking a decision or accepting responsibility’.Lapena’s own troops called him ‘Dona Manuela’, which, figuratively speaking, translates as something along the lines of ‘Big Girl’s Blouse’.4

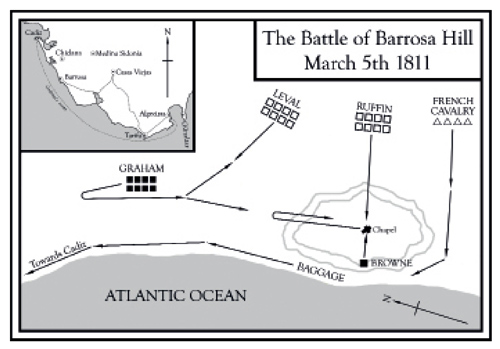

The next day the allies set out. After several fatiguing forced marches, by 5 March Lapena’s army was nearing Cadiz, and here, at Bermeja, the Spanish vanguard ran into the French. Lapena’s men fell on 2,500 troops under General Villatte, while from Cadiz Spanish general Zayas laid a bridge of boats across the harbour, so his garrison could sally forth and complete the pincer movement. Under fire from north and south, the French fell back. Lapena was pleased with the ease of his victory, but for one of Graham’s aides-de-camp it was that very ease which aroused suspicion. ‘That is not like the French’, observed Lieutenant Stanhope.5

While Lapena’s Spanish troops were savouring their triumph, Browne’s flank battalion was still several miles away at Barrosa Hill, which was, in Graham’s view, the tactically critical position south of Cadiz. To reach Barrosa, Campbell’s men had endured another of Lapena’s all-night marches: seventeen hours without a stop for food or water. Footsore and flagging, but reassured now Lapena had put the French to flight, Campbell’s men tried to get some rest, the baggage train likewise. Nearby, the two squadrons of hussars of the King’s German Legion,* the only cavalry serving with Graham under the British flag, dismounted and loosened their saddles.6

Instead of chasing his beaten enemy, Lapena stayed put and ordered the British north to join him. Graham protested that positioning the allied army near the isthmus leading to Cadiz would just hem them in and leave them susceptible to a French attack. Lapena compromised, allowing Browne’s flank battalion to remain at Barrosa Hill, along with five Spanish battalions as a rear guard. Graham would lead the rest of his men through the woods to the north of Barrosa Hill and, once they reached Lapena outside Cadiz, the rear guard would abandon their hill and follow. It was exactly what Victor wanted. The French troops Lapena had defeated at Bermeja were just a foretaste. Victor had redeployed most of his men to the east at Chiclana. And so as Graham left for Cadiz, Victor emerged to fall on his flank.

Victor split his force in two, one half heading for Barrosa Hill, the other half, under General Leval, towards the woods. Campbell’s company was resting on the western slope when the French were sighted advancing from the east. An anxious Colonel Whittingham, serving with the Spanish cavalry, rode up to Browne to ask his intentions. ‘What do I intend to do, sir? I intend to fight the French!’ came the reply. ‘You may do as you please, Colonel Browne, but we are decided on a retreat’, replied Whittingham. ‘Very well, sir, I shall stop where I am, for it shall never be said that John Frederick Browne ran away from the post which his general ordered him to defend!’7

This spat was enough to convince Spanish generals Murgeon and Beguines that it was time to leave. Campbell watched as all five of their battalions, after some half-hearted skirmishing, started in full retreat.8 The baggage train followed; pack horses, nostrils flaring, careering along the sands, past upended carts circled with spilt rations and ammunition, as the able-bodied joined the desperate stampede northwards along the beach towards Cadiz and safety.

From the brow of the hill Browne could make out enemy infantry drawing closer. With the Spanish gone, he had barely 500 men to repel 2,500 Frenchmen.9 Victor had a further 4,000 men in reserve behind them. Five hundred French cavalrymen were skirting round the hill, to seize the coast road. All that stood in their way was two German and four Spanish cavalry squadrons – that is, if Whittingham stood his ground.

The one place offering a modicum of protection was a ruined chapel at the brow of the hill. Browne ordered a handful of men to occupy it and loop-hole the walls, while outside Campbell and Seward formed their company up with the rest, making three sides of a square, each side four men deep, with the chapel forming the fourth.10 But besides the enemy cavalry encircling them and enemy infantry heading their way, French artillery was now closing in. The flank battalion risked being surrounded and pulverised. Browne may have been quixotic but he was not suicidal. Rather than making a death-or-glory stand, he ordered his men to make for the trees.

When Graham, in the thick pine woods to the north, received news of the French offensive in progress, ‘he seemed at first to doubt the truth of this intelligence,’ as one officer recalled, ‘but a round shot came amongst us and killed Captain Thomas of the Guards. He was then convinced of its accuracy.’11 Graham directed Colonel Wheatley’s brigade to stop Leval as he neared the wood, while the rest would double back to engage the French troops advancing on Barrosa Hill. Given the difficulty of manoeuvring an army through a forest, this gambit would take some time.

In the interim, French infantry had overrun the chapel. As Browne led his battalion towards the trees, enemy cavalry bore down upon them, and the order to form square was barked out. ‘Be steady, my boys, reserve your fire until they are within ten paces, and they will never penetrate you’, roared Browne.12 The enemy, sabres raised, mounts snorting, accelerated towards them. Campbell’s company prepared to fire but as the French dragoons covered the final few yards, the hussars of the King’s German Legion swept past and laid into them.* The confusion gave Browne enough time to lead his men to safety. By now Graham’s troops were disgorging from the forest in disarray. The general emerged furious. ‘Did I not give you orders to defend Barrosa Hill?’ he demanded. ‘Yes, sir’, replied a stunned Browne. ‘But you would not have me fight the whole French army with 470 men?’

Graham made it quite clear that he would, and that he would brook no denial. Browne was to turn back and retake the hill. The rest of the British army was still not out of the woods yet, and Browne’s flank battalion was the only one in a fit state to stem the French advance. Graham instructed Browne to form his 470 men into a line, two deep, to mount a frontal assault up the slope. It was the first time Campbell had led men in battle, and for all their light infantry expertise, they were to be thrown at the enemy with no tactical sophistication. For Graham, sacrificing Browne’s contingent was an acceptable price to pay to buy time for the rest of his army to regroup. So, after being so close to battle at Vimeiro and Corunna, after all the hunger, disease and death of the last three years, it looked like Campbell was to end his days as cannon fodder.

‘Gentlemen, I am happy to be the bearer of good news!’ Browne announced. ‘General Graham has done you the honour of being the first to attack these fellows. Now follow me, you rascals.’ And with that he strode up the hill, lustily belting out ‘Heart of Oak’.13 Campbell marched forward, cavalry sabre in hand, a few yards from Seward, their neat row of infantrymen behind them. Once across the small ravine at the foot of the hill the ground was virtually featureless, with barely a hollow to shield them from enemy fire. As the battalion advanced, eyes fixed on the summit, French artillery and infantry at first held fire and then with a deafening roar the guns on the crest of the hill exploded, scouring the hillside with grape shot. In unison the muskets of three enemy battalions fired. The effect was carnage. Two hundred of Browne’s 500 men were killed or wounded. Browne had no artillery to answer the French, and no reserves to call upon. He could only rally his men and, pointing towards the enemy, roar at them, ‘There you are, you rascals, if you don’t kill them, they will kill you. So fire away!’14

Campbell and Seward re-formed their men in a new, tighter line, but the enemy fire was overwhelming. Another artillery volley brought down a further fifty men, leaving Browne with barely half his original force. From the 2/9th, Captain Godwin, Lieutenants Taylor and Robinson, five sergeants, one drummer and seventy men from the ranks had fallen. Godwin had been waving his sword and willing his men on when a musket ball hit him in the right hand. Seward was also among the casualties. The battalion started the day with twenty-one officers; Campbell was now one of just seven left unscathed, including Browne. As he looked around Campbell realised that with the captain and three lieutenants from the 2/9th hors de combat, command of both companies now rested with him.15

The battalion had displayed exemplary, indeed wasteful courage, but there were limits to their endurance. Despite Browne’s order to form a new line, the men instead scattered, finding cover wherever possible, keeping up an erratic musket fire, and waiting for the inevitable charge from their enemy.16 But then to his right Campbell caught sight of movement. The 95th Rifles were streaming out of the woods, their dark green uniforms just visible in the thicker cover further round the hill. Behind them were the Guards and the artillery. Enough troops had made it through the wood to assault the hill. Browne’s men, by an act, in Oman’s words, of ‘absolute martyrdom’, had tied up the French for long enough. Now Campbell just had to hold his ground.

Victor’s troops still had the advantage in numbers and terrain. Four battalions charged down the slope to stop the British fight-back but, as at Vimeiro, they found that their old tactic of impetus, brute force and Gallic hullaballoo failed to overawe their enemy. On top of the hill, Victor, commanding in person, ordered two battalions of grenadiers to revive the offensive. While the Guards, the 95th, and now the 67th Foot, had been fending off the French onslaught, Campbell’s men had been lying quiet. As Campbell saw the French bearing down on the British line to his right, he ordered his men to stand and fire into their flank.17 With Victor’s troops wavering, Graham rode up, shouting ‘Men, cease firing and charge!’Campbell led his two companies forward, maintaining their fire on the French flank, while the British further round the slope pushed up the hill.18

The momentum of the battle was now with Graham. To the north-east, the British emerged from the wood in a long line, to catch Leval’s troops by surprise. The French assumed that it was merely the first wave, rather than all the troops available. Liberal use of the bayonet, with instrumental support from the Portuguese detachment, prevailed and soon the French division was taking to its heels. Leval desperately threw his reserves forward but they were so demoralised that they scarcely came within range before turning back. What really sent the French away with a flea in their ear was the capture, by the men of the 87th (commanded by Major Hugh Gough), of an Imperial Eagle,* the first of the war.

Victor was trying to impose some order on the shambles that had once been his army, when all at once two squadrons of German cavalry charged the massed French dragoons. Their sheer audacity unmanned the French and Victor’s army started into a full retreat. Now was the moment to trounce them, but Graham was short on men and his Spanish allies were reluctant. Without Spanish help, Graham thought his infantry too worn out to harry the French. Though bruised and battle-scarred, Browne’s men rushed forward, in skirmishing order, ready for action, but Graham called them back.19 Victor was left to withdraw to Chiclana.

The battle had raged for just an hour and a half. Most corps had incurred losses, but none so cruelly as Browne’s battalion. Graham had been ruthless. Kinglake, the Crimean historian, was sure that a general ‘At any fit time must be willing and eager to bring his own people to the slaughter for the sake of making havoc with the enemy, and it is right for him to be able to do this without at the time being seen to feel one pang.’20

After Barrosa, Campbell was never so sure. He had left Gibraltar the junior lieutenant of the light company and now found himself in charge of both flank companies, filling the role of a senior captain. He was still just 18 years old. After close on three years waiting and watching, he had been at the crux of one of the bloodiest encounters of the war. Campbell modestly recorded that Graham ‘was pleased to take favourable notice of my conduct’.21 Outwardly anxious ‘to do good by stealth and blush to find it fame’, in truth Campbell had no misgivings about advertising his deeds when professional advancement required it. He knew full well the impact he had made, and in future, if ever he needed a reference, it was to Graham he turned first.

![]()

Though the French had been soundly beaten, Graham’s ambition of raising the siege was no nearer. Both sides were left much as they had been before. Within days Victor was again master of his old entrenchments. For a man of illimitable vanity, the next logical step was to declare the Battle of Barrosa a French victory.

Just ninety of the original 160 men from the 2/9th were fit for duty. The rest needed a surgeon or an undertaker. To add to Campbell’s problems, a new disease broke out in Cadiz, labelled the ‘black vomit’.22 Fortunately, just three days after the battle, Campbell’s depleted companies sailed for Tarifa, before returning to Gibraltar on 2 April.

They enjoyed only a few weeks’ rest before Graham selected them to join the expedition to raise the French siege of the port of Tarragona. On 21 June a force under Colonel Skerrett set out from Gibraltar in six ships, arriving off Tarragona five days later.23 Graham had ordered Skerrett not to land if he thought the mission might end in surrender. Having gone ashore to meet the garrison, Skerrett concluded that their position was beyond remedy, and so kept his troops aboard.

On 28 June French troops stormed the town. It took them just half an hour to take the outer defences. Campbell watched from offshore as Tarragona was sacked and then set on fire. Two thousand civilians and 2,000 soldiers were butchered, and 8,000 Spanish troops taken prisoner.24 Twelve hundred British soldiers would not have tipped the balance.

Despite this damp squib, Campbell had impressed Graham enough to secure a new assignment: a much prized posting as an aide-de-camp (ADC). A staff post like this was the fastest route to high rank. By convention, it was an ADC who carried home a victory despatch, and his reward was immediate promotion. Campbell’s linguistic skills, notably his fluency in Spanish, must have helped. He was appointed to serve with ‘General Livesay’,* himself under the command of General Francisco Lopez Ballesteros, one of Spain’s most celebrated soldiers.

All went well initially. Livesay and Ballesteros had spent most of 1811 harrying the French in and around Andalucia, and on 25 September they defeated a whole column at San Roque before taking 100 enemy soldiers prisoner on 5 November.25 Frustrated at this new nuisance, Soult sent Victor to subdue Ballesteros and then storm Tarifa.

By 20 December Tarifa was surrounded by ‘four or five thousand Infantry and 250 or 300 Cavalry’.26 Following a concerted French offensive on New Year’s Eve, the Governor of Gibraltar sent an extra detachment. The natural choice was the flank companies of the 2/9th and so Campbell, having finished his time as ADC, led his light company to Tarifa once again. The allied position there was growing worse. The defences had been weakened by Victor’s assault and the British command was divided over what to do next. Fortunately, the French decided the question for them. On 4 January, his trenches filling with mud, his guns sinking into the ooze, Victor started to pull back his artillery. At 3 a.m. the next morning he began a full retreat. Campbell was in Tarifa for just a few hours before the enemy vacated their lines.** The siege had cost the French 500 men, more than 300 horses and mules, and three guns.27 British casualties were fewer than seventy.

Campbell’s service with Livesay in late 1811 should have laid the foundations for great things. Instead it became a millstone. While Campbell spent a quiet 1812 in Gibraltar, Ballesteros’s pride outgrew his talents. Piqued by Wellington’s appointment to supreme command of the allied armies in October 1812, he refused to serve under him. He was swiftly arrested and imprisoned. Any association with Ballesteros or his acolytes was a black mark on an officer’s record. Campbell was denied another staff appointment for ten years. It was an object lesson in the dangers of hobnobbing with generals: one benefited from their victories and suffered their defeats by proxy.

Wellington, meanwhile, enjoyed a stellar 1812. Having invaded Spain, he took Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajoz by siege, before winning a signal victory at Salamanca. In February 1812 he was raised to Earl and that August to Marquess of Wellington.*** A month later parliament voted him a lordly £100,000 towards his future housing needs and the Garter as an amuse bouche.

That autumn his luck petered out. He was thwarted at Burgos and had to withdraw to Portugal. Disease chipped away at an army already weakened by an arduous retreat. The one good omen in those depressing winter months was the news of Napoleon’s costly withdrawal from Moscow. Campbell’s colleagues in the 1/9th limped back from Burgos with heavy casualties. The powers that be decided to sacrifice the second battalion to reinforce the first, and in early 1813 Campbell and 400 men transferred to the first battalion overwintering in Portugal, while the rump of the 2/9th returned to Canterbury. Campbell was again given command of the light company. He found the men recovered from the ordeals of the previous year. James Hale, now a corporal under Campbell, noted that ‘having good provisions, rest, and a little money to purchase a few good bottles of wine, all past fatigues were smothered’.28

With his army recuperated, and the weather improving, Wellington felt confident enough to launch a new campaign to force the French back to the Pyrenees. One of the occupational hazards of having a reputation for hard fighting is a tendency to be placed in the vanguard, and the 1/9th were chosen to be among those spearheading the advance, in General Hay’s brigade, itself part of the 5th Division under Sir James Leith. Since Campbell’s first campaign in the peninsula, the scale of the war had grown exponentially. Wellington now commanded more than 75,000 British troops, besides tens of thousands of Spanish and Portuguese.29 The 5th Division was just one of several in a corps d’armée commanded by Thomas Graham. ‘Next to Lord Wellington’s self, there is no one who will take so good care of us’, wrote Gomm.30

The allies would march into Spain in three columns, rendezvous at Valladolid and then assault Burgos and so complete the job Wellington had left unfinished the previous autumn. On 14 May Campbell’s men started out, soon crossing the River Douro via the ferry at Peso de Regoa before meeting up with the rest of Graham’s force.31 For the first time Campbell kept his own journal of the campaign. Crossing the Esla by pontoon bridge on 1 June was his first entry.32 With age his prose style improved and he became more forthcoming, but with its arid concern for the minutiae of road, weather and terrain, this early memoir reads like a tactical appraisal. Then again, Campbell’s omissions are revealing in themselves. He makes no mention of senior officers, except when he dined with a general. He voices no opinions or grumbles, instead maintaining a prim, matter-of-fact detachment as if he were writing for an exam. He is never contemplative or critical, always protective of his own thoughts, the strictly impartial narrator, even when at the centre of the action. This is the work of either a young officer trying to impress or an obsessive with a growing inability to switch off. Posterity and self-improvement seem to be his motivation. Perhaps Campbell, in his precocious way, regarded it as a valuable scientific account, the product of a very serious-minded lieutenant, anxious to observe and record. Its striking impassivity suggests that this was a role he enjoyed, that of the outsider looking in.

Initially, he had little to record. By 5 June Campbell had reached Medina de Rio Seco33 without ever once running into the enemy. French resistance was negligible. At Zamora and Toro the emperor’s troops simply ran away before the allies’ approach. The French were expected to make a stand at Burgos, but instead Wellington found it deserted. At each town and village the allies were hailed as liberators, greeted with bread and wine and shouts of ‘Viva los Ingleses!’34

The offensive was proceeding on, or ahead of, schedule. Underlying that speed was abundant food. For Wellington, ‘No troops can serve to any good purpose unless they are regularly fed. A starving army is actually worse than none.’35 Rations were the priority. Not even the tiniest component of supply escaped the marquess’s busy mind. His overhaul of regimental kitchens reads like the work of a restaurateur.36 Having seen shortages ruin Moore’s army, Campbell was now witness to a master class in the application of method to this Cinderella arm of the military. It made a deep impression. While other generals were game to pitch in regardless, Campbell only moved when his supplies were secure. By the 1850s, when British victories had become so effortless as to convince young officers that dull matters like provisions were unimportant, Campbell was one of the few generals left who fully appreciated their importance, having witnessed an army on its knees at Corunna, and one fighting fit under Wellington. It was why Campbell’s men survived better than most in the harsh Crimean winter of 1854–55 and why he managed to supply an army across thousands of miles of hostile Indian territory with scarcely a hiccup. Campbell might have been pilloried for his hesitation, but it was no more than Wellington’s shrewd preparedness.

By 15 June Campbell had crossed the River Ebro and entered a verdant new land. ‘I can conceive of nothing finer than the whole route from the banks of the Upper Ebro across the mountains’,wrote Gomm.37 ‘In a scene so lovely, soldiers seemed quite misplaced’, added another officer. ‘The glittering of arms, the trampling of horses, and the loud voices of the men, appeared to insult its peacefulness.’38 Even Campbell felt ‘the fertile, rich and beautiful valleys’39 deserved a mention. Wellington’s columns now massed as one and with Graham’s troops up front, advanced parallel to the Ebro. By the 18th, they had reached Osma. Around noon Campbell spotted Frenchmen up ahead. They were General Maucune’s troops marching north to Bilbao.40 ‘The meeting was as great a surprise to them as to us’, he recalled. Together with other light companies, and with artillery in support, Campbell was ordered to advance. As they caught sight of the blue enemy uniforms, his troops surged forward. ‘This being the first encounter this campaign, the men were ardent and eager, and pressed the French most wickedly’, Campbell explained.41 ‘We continued advancing, driving them before us like a flock of sheep for nearly two leagues, giving them a few shots when most convenient’, remembered Hale.42 The men advanced through the lightly wooded countryside, exchanging fire until sundown. ‘I found myself incapable of further exertion from fatigue and exhaustion occasioned by six hours of almost continuous skirmishing’, admitted Campbell.43 With 300 of the enemy taken prisoner, along with their baggage,44 it was a clear allied victory, but this was just the curtain-raiser.

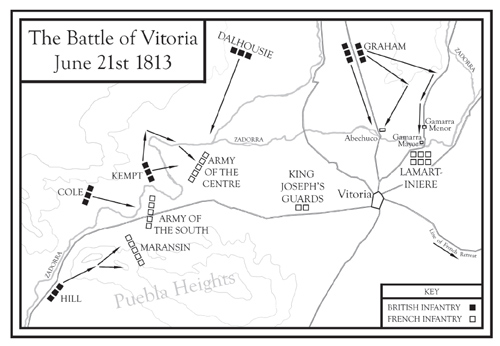

King Joseph’s troops had endured weeks of retreat. The honour of France and of the Bonapartes was at stake and Joseph knew with every mile of ground lost to Wellington, his brother’s teeth ground all the louder. For Joseph, more bon viveur than beau sabreur, the greater worry was his ponderous baggage train stuffed with plunder, specifically how to get it safely back to Paris, but he knew that to avoid Napoleon’s wrath when he got there he had first to make a stand. He settled on Vitoria. Here Joseph was sure that he could, if not reverse, then at least stem the allied advance. The dished basin round Vitoria provided a scenic 12 by 6-mile war stadium, with ample scope for that French favourite, artillery, to come into play. The town lay at the eastern end, with roads spreading out from it like a spider’s web. From the north-east corner of the basin flowed the River Zadorra, running westwards past the town and, after a sharp hairpin turn, snaking south-west through the mountains. It afforded Joseph a natural defensive barrier.

Wellington pushed forward with the utmost haste, reaching Vitoria on 20 June. He planned to mount a bold, simultaneous assault from all sides, throwing a tightening noose around the French. The challenge was co-ordinating his disparate battalions over such a wide arena with nothing but gallopers to relay messages. If one section of the line failed, the French could easily regain the initiative. Graham’s corps, at around 20,000 men the strongest portion of Wellington’s army, would bear down on the French flank from the north and cut off their retreat. The ferocity of his attack would depend on how Lord Dalhousie’s two divisions fared to Graham’s right. Graham was to keep mobile, avoid getting bogged down in fighting near Vitoria, and be ready to prevent the enemy escaping eastwards. However, should Dalhousie gain the upper hand, Graham was to grab the opportunity to advance.

So far that month, Campbell’s only rest had been back on 12 June.45 Already tired after a gruelling journey through the mountains, he had to march his company through the night to keep to Wellington’s plan. ‘We formed our camp about two leagues from Vitoria, on a sort of wild wilderness place, among brambles, thorns, etc and to my thinking, almost all sorts of vermin’, complained Hale. The men were issued with their meat ration but, having left almost all of their kit in the rear, had nothing to boil it in, so instead broiled it on the coals of the campfires.46 Having snatched a little sleep, they awoke an hour before dawn and, after a breakfast of ½lb of bread per man, formed up to march on Vitoria. By 10 a.m. the early morning mists had given way to clear blue sky and as Campbell’s company reached the heights immediately north of the town, they ‘had a fine view of the French army … formed all ready for combat along the river for three or four miles each way’.47

Wellington’s offensive started promisingly. Allied troops under General Rowland Hill crossed the Zadorra to the south, and took the Puebla Heights. Stiff French resistance slowed his advance, but Hill could be content that he had captured the first objective. By 11 a.m. Wellington himself had started to press in from the west. It was imperative that the divisions kept up with one another as they closed in, but round the valley at Graham’s section of the line there seemed precious little action.

Graham’s offensive had stalled. Finding the whole of General Reille’s Army of Portugal* opposing him, and conscious of his orders to avoid getting entangled in a pitched battle too soon, he prudently halted short, waiting for Dalhousie’s troops to appear to his right, as instructed. However, the arrival at 11 a.m. of 5,000 guerrillas under the command of General Longa persuaded Graham to push forward, and so, a little after noon, Campbell received the order to advance. Ahead were the villages of Gamarra Mayor, Gamarra Menor and Abechuco, each a little north of the river. The British needed to take all three.

Major-General Andrew Hay’s brigade was to take the heights above Gamarra Mayor, his right flank covered by Campbell’s light company, but as they advanced, the French pulled back towards the stronger defensive line of the Zadorra. Hay’s brigade paused. Campbell recorded that:

While we were halted – waiting it was said, for orders – the enemy occupied Gamarra Mayor in considerable force, placed two guns at the head of the principal entrance into the village, threw a cloud of skirmishers in front amongst the corn-fields, and occupied with six pieces of artillery the heights immediately behind the village on the left bank.48

Further away, beyond the French guns, he could make out more enemy infantry waiting in reserve.

Frustrated at the lack of visible progress from Graham, at 2 p.m.** Wellington sent an unambiguous order to press home the attack and storm the three villages standing in his way. To reach them, the British would have to cross open ground and suffer the French grapeshot. Even then, the enemy could still retreat and make a stand at the river, but Graham had to maintain momentum. He ordered Major-General Robinson’s brigade to assault Gamarra Mayor, with Campbell’s light company detached to cover its right flank. Opposing them was an entire French division under General Lamartinière.

Immediately Campbell neared the village, he encountered ‘a most severe fire of artillery and musquetry … from behind garden walls, and the houses which the enemy had occupied’. The air was clotted with lead, the French response so ferocious that Robinson’s advance was stopped in its tracks.*** Having regrouped, the British charged forward again, and, in Campbell’s words, ‘did not take a musquet from the shoulder until they carried the village’,49 overwhelming the French and forcing them to withdraw over the bridge. As Robinson’s men followed, they were gunned down by artillery on the far bank. Through the lingering gunsmoke, French infantry emerged in a timely counter-attack. The British, winded, pulled back.

There then followed a succession of attacks and counter-attacks, a murderous ebb and flow in which neither side gained the upper hand. The British were limited by the narrow street that led to the bridge, allowing few to muster before charging forward and restricting any assault to a fraction of Robinson’s full strength, but still they had to try. Campbell was ordered to cover the left flank of a fresh advance by the Royal Scots and the 38th Foot. Vigorously executed by men new to the fight, it forced the French back from the bridge once more, only for the British to be repulsed again by an enemy counter-stroke.50

Gamarra Mayor was the exception. By now the other two villages, Abechuco and Gamarra Menor, were Graham’s. To the west, Wellington was finding the French response reassuringly inept. Generals Picton and Kempt had secured the bridges across the Zadorra, and Hill’s men continued to advance from the south. All across the plain Joseph’s armies were on the back foot. The valley was strewn with their relics: abandoned muskets and orphaned shakos. In desperation, Joseph gave the order to fall back to the town. From there his only means of escape was the road due east to Salvatierra. Responsibility for preventing the enemy from slipping the noose lay with Graham. It was now imperative that he take the road before Joseph’s army could flee along it, but Gamarra Mayor still barred the way. Here the two sides were locked in stalemate, each with such a withering fire trained on the bridge that neither could cross. Campbell had deployed his light company to the left of the village, to harry the enemy on the far bank and beat back any French attempts to ford the river. Ordered not to ‘expose ourselves more than we could help, nor to advance one inch without an order’, wrote Hale, ‘we formed ourselves under cover of a bit of a bank that was about knee high, and in this position we continued skirmishing for more than two hours’.51 Opposite, the French skirmishers had been relieved three times, but Campbell’s men had to continue without a rest.52 As afternoon turned to evening, there seemed to be no way out of the deadlock and no way to dislodge the French on the far bank. If Graham could not push forward soon, Wellington’s noose would fail.

Then, quite unexpectedly, the enemy on the bank opposite began to fall back.53 Seizing the initiative, Campbell led his company towards the bridge. Finding it ‘heaped with dead and wounded’, the casualties ‘were rolled over the parapet into the river underneath’54 to make way for the allied infantry and cavalry. One of Picton’s brigades, together with the hussars, had swept down and attacked Reille in the rear, forcing him to retreat before he was cut off. ‘When we crossed the bridge the whole of the British cavalry covered the plain of Vitoria’, recalled Gomm. ‘I assure you 4,000 British helmets reflecting the rays of the setting sun across the plain was rather an animating spectacle.’55 What Oman called a ‘brilliant and costly affair’ was finally over. ‘By God, Graham hit it admirably!’ declared Wellington.56

By now it was eight o’clock and the light failing. Campbell’s men had been marching or fighting since 3 a.m. and they were dead on their feet, their mouths black from biting cartridges. Ensign Sanders and nine men lay dead, with a further fifteen wounded,57 remarkably light casualties given the ferocity of the fighting, and a tiny fraction of those incurred at Barrosa. They stopped for the night in a bean field. Flour pilfered from the village of Zurbano, the beef ration in their haversacks and the beanfeast around them made supper, enhanced by the timely arrival of the commissary with the wine ration. As a tired James Hale recalled, ‘We laid ourselves down on the turf, under the branches of the trees, as comfortable as all the birds in the wood.’58

While the 1/9th rested, in Vitoria all hell was breaking loose. Crammed with French plunder, the town offered spoils ‘such as no European army had ever laid hands on before, since Alexander’s Macedonians plundered the camp of the Persian king after the battle of Issus’.59 ‘Well, they have always abused me for want of trophies. I hope we have enough today!’ exclaimed Wellington.60 Army pay was ‘a retaining fee against the day of prize money’, as one historian put it.61 Plunder was the real pay-off. It was supposed to be audited, sold and the proceeds distributed by army prize agents, so that all got a fair share, but when the loot passed into official hands it not only fell prey to an ever-lengthening queue of claimants demanding its restitution, it also dwindled mysteriously in size. ‘A great deal of it will never see the light, except in England’, complained one ensign. ‘Commissaries and their clerks have smuggled fine sums.’62 He was proved right: the subalterns who relied on the prize agents at Vitoria eventually received slightly less than £20 each, six years after the end of hostilities.63 ‘Our Division received more Iron and Lead than Gold or Silver’, complained Lieutenant Le Mesurier.64 The experienced soldier knew the best policy was quietly to fill one’s boots* and deny everything.

So far the only spoils for Campbell had been a large Irish stew, but by noon the next day the camp was, in his words, ‘filled with plunder’.65 Some men walked away from the battlefield set up for life, but not Campbell. Vitoria set the pattern for him for the next fifty years. Though desperate for the independence that wealth promised, he lacked the ruthless single-mindedness to get it. There were troops at Vitoria who risked court martial and death, knowing a good day’s spoils could buy a nice little estate in the country or promotion to lieutenant-colonel. Vitoria was the first of many towns Campbell saw scavenged, but every time he stood aloof. In China, nearly thirty years later, he explained his reluctance to his sister:

Although I visited many private dwellings of rich people, full of costly and curious things, I did not take anything … Not that the desire to possess was not upon me as with others, but that I foresaw the certainty of being called upon to punish others for the same proceeding if the war had continued, and I wished to stand right with my own conscience.66

![]()

Having routed the French, Wellington wanted to keep them on the run. The 9th Foot set out from Vitoria on the afternoon of 22 June as part of the force assigned to find the French army under Marshal Clausel, heading for Vitoria. The rest of the allied troops would march for Tudela to catch King Joseph. However, a few days’ chase convinced Wellington that his enemy had too great a head start and on the 29th he called off the pursuit, leaving Clausel and Joseph to escape over the Pyrenees.

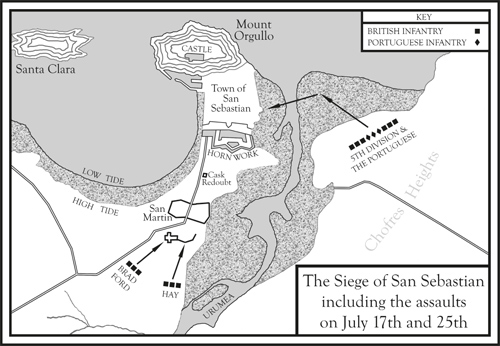

Vitoria had knocked the heart out of Joseph’s army, but Napoleon’s soldiers still held several key Spanish towns, while tens of thousands more troops lay in wait over the French border. Wellington, his supply lines from Portugal now dangerously extended, decided his first priority was to clear north-eastern Spain of the lingering enemy garrisons at San Sebastian and Pampeluna. The port of San Sebastian would be of particular benefit, lying near to the French border, and offering a convenient supply base for the advancing allied army as it headed east. It was named in honour of a Praetorian guardsman who, having converted to Christianity, survived a hail of arrows only to be beaten to death on the orders of the Emperor Diocletian. To besiege a town named after a military martyr looked like tempting providence.

By 28 June the Spanish had the shore approaches to the port blockaded. On 6 July Wellington dispatched Graham to appraise the French defences and formulate a plan of attack. Graham was still recovering from being hit in the groin by a spent cannonball, but nevertheless threw himself into the task with his customary vim. He reasoned that to have any chance of carrying the place he needed more troops, so the 5th Division (including the 1/9th) were sent to help. Campbell’s company arrived exhausted outside San Sebastian on 10 July. The thrill of victory at Vitoria had given way to dismay at the fruitless pursuit of Clausel. The weather didn’t help. Rain had ‘made the roads so deep that the Troops are almost without shoes’,wrote Le Mesurier.67

The men pitched their white tents in hollows on the high ground a couple of miles south of the town, to hide them from the French garrison. From here Campbell had a superb view of this scenic but tough little port. San Sebastian sat on a spit of land jutting north into the Bay of Biscay, ending in a tall rocky outcrop called Mount Orgullo with a castle and a lighthouse on top. Houses and shops occupied the middle of the isthmus south of Orgullo, enjoying the protection of the sea on both sides, which lapped the walls at high tide. Amphibious assault from the north was rendered near impossible by the natural rock fortress of Mount Orgullo. However, though imposing, this headland was so vertiginous that its guns could not lower their elevation enough to fire on the town below in the event that it was overrun.68

To the south, San Sebastian was guarded by an elaborate ‘hornwork’, a high curtain wall more than 350ft long, dominated by a massive bastion in the centre, and protected by a ditch and glacis. At each corner was a further demi-bastion providing a line of fire on troops attacking overland from the south, or from the seaward fronts. South-west of the town were the Heights of Ayete and at the foot of these hills, where the isthmus met the mainland, stood the convent of San Bartolomé, now occupied and fortified by the French. To the south and east of San Sebastian lay the estuary of the River Urumea, and across this channel the Chofres Heights (see Plates 4 and 5).

Given its formidable natural defences, Wellington’s best chance was to batter down the hornwork and the walls on either side, and storm the town. Having surveyed the town, Major Charles Smith of the engineers advised a thunderous barrage from the hills overlooking the town to the east of the estuary,* to pummel the east wall to dust and leave a breach through which the British could pour.

The first objective was the convent at the foot of the isthmus, commanding the ground south of the hornwork. ‘For many years the asylum of all the females of noble family … who took the veil’,69 it was rather grander than average. By 13 July Graham had his heavy guns in position. Everything from 8in howitzers to 68-pounder carronades** drew a bead on the convent, but after a two-day cannonade the walls were still obstinately perpendicular.70 Graham was sure the enemy inside must be on the brink of surrender, but an assault by the Portuguese on the 15th was beaten back convincingly, although according to Campbell it was only ever an attempt to ‘ascertain what number the enemy kept in his works’.71 The guns resumed firing the next day and this time the convent caught fire.

Graham scheduled a full-scale attack for noon on 17 July. Major-General Hay’s column would take the fortified graveyard, lunette*** redoubt and ancillary buildings to the right. In the vanguard would be the 4th Caçadores, an elite Portuguese light infantry unit, followed by men of the 1st Portuguese Infantry. In support would be three companies from the 1/9th led by Lieutenant-Colonel Crawfurd, including Campbell’s light company. Behind them, in reserve, would be three companies of the Royals Scots. A second column, commanded by Major-General Bradford, would bear down on the main convent building. The 5th Caçadores and the 13th Portuguese Infantry would spearhead this attack. Behind them would be the grenadier and two ordinary companies from the 1/9th, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Cameron, with the rest of the 1/9th in reserve.72

Having fired 2,998 rounds into the convent, the allied artillery fell silent and the infantry prepared for the assault. At the last minute the Portuguese were removed from the vanguard of the second column. Instead, wrote Cameron, ‘General Bradford, no doubt for the best reasons in the world, ordered my three Companies to make the assault.’ Cameron ran into French artillery, but managed to return fire with two 6-pounders of his own. He had been ordered ‘to halt under cover of a stone wall within fifty yards of the Convent until a signal should be observed from the right attack’, but he could see Frenchmen running from the earthworks, and without waiting for the order, ‘sprang over the wall and moved rapidly against a strong body of the enemy posted outside the Convent’.73

Hay’s offensive ‘was begun by the Portuguese on the redoubt in very good style’, reported Le Mesurier, ‘however they went no further than a hedge under the Redoubt, when our people were obliged to show them the way’. ‘Notwithstanding the very praiseworthy actions of Major Bennett Snodgrass to animate the Detachments of Portuguese Troops which he commanded on this occasion,’ explained Cameron, ‘the honour of leading the attack on that side also was necessarily yielded to the Companies of the 9th British Regiment.’

Crawfurd’s men ran into heavy fire from the lunette. The only other way in, through the remains of the outbuildings pulverised by the artillery, was blocked by smouldering debris too hot to cross. But then suddenly the lunette ahead was abruptly deserted, as the enemy wilted under the force of Cameron’s assault on the main building. At the head of the light company, foremost of Crawfurd’s three companies, ‘Campbell led in fine style through the hedge, over the Ditch and into the Redoubt which the French abandoned’, explained Le Mesurier.74

Meanwhile, Cameron was chivvying the last Frenchmen from their defences. ‘The enemy escaping by the windows and other outlets, joined those that had been at that moment driven by the Grenadiers from the Convent, retreating through the suburb of San Martin, continuing their fire upon the 9th, whose numbers were now much reduced’, he recalled. The French took cover but, explained Cameron, ‘the remaining Companies of the Regt. having been sent for by their Lieut. Colonel, arrived in time to assist in dislodging the enemy from the ruins of San Martin’,75

Crawfurd had been ordered to limit his assault to the convent and nearby buildings, but Cameron was already charging on towards the hornwork. Further down the isthmus was another redoubt with a distinctive parapet made from earth-filled casks. Campbell’s blood was up and, perhaps with an eye to being named in dispatches, he rushed down the hill, sword in hand, his company just behind. Leading his men inside the redoubt, he swiftly subdued the enemy and seized the position, but French muskets on the hornwork targeted them, and a detachment from the garrison launched a sortie to recapture this outwork.76 Outgunned, the light company fell back. Storming the convent cost seventy casualties. Campbell made it back unscathed. Graham noted in his dispatch that his ‘gallantry was most conspicuous’. Campbell recorded the assault in his journal with modest concision: ‘Convent taken’.77

Four days later the British had a rare stroke of luck. While cutting a parallel across the isthmus, Lieutenant Reid’s party discovered a large drain nearly 4ft wide. Reid headed down the tunnel and found a door, plumb under the hornwork itself. It was a ready-made mine. The engineers soon had thirty barrels of powder lodged at the end, primed to blow.78 By 23 July the artillery had knocked a hole 100ft wide in the east wall of the town, as well as a second, smaller breach further north. Everything was ready for the allied assault.

The estuary was only traversable when the tide was out, so the attack was arranged for the 24th, when low tide coincided with daybreak. The Royal Scots were to advance first and head for the larger of the two breaches, with the 9th in support. The 38th Foot behind them would take the second breach. Campbell was given the most treacherous and prestigious job of all, command of the ‘forlorn hope’. His task was to lead a storming party of picked men and secure the breach for the men behind. Responsibility for the success of the enterprise rested with him. ‘I was placed in the centre of the Royals with twenty men of our light company, having the light company of the Royals as my immediate support and under my orders’, explained Campbell. ‘I was accompanied also by a party with ladders, under Lieutenant Machel of the Engineers, with orders, on reaching the crest of the breach, to turn to and gain the ramparts on the left.’79

Leading a forlorn hope was perilous, but if you survived it was the surest route to promotion. Wellington was notoriously reluctant to promote officers for merit or valour, but this was one instance when he was prepared to make an exception.* For Campbell it was his best chance for a captaincy without purchase. It was obvious the war was approaching its denouement, after which the army would shrink drastically. There were twenty-five lieutenants senior to him in the 9th. In peacetime it would be years, perhaps decades, before he got to the top of the list. Leading a forlorn hope was the only way to jump the queue without paying. When asked how he felt before the assault, Campbell replied, ‘Very much, sir, as if I should get my company if I succeeded.’

By 3 a.m. the troops were ready in the forward trenches but across the estuary Campbell noticed the French ‘feeding the fire near the breach which had been made in the eastern flank wall’.80 Leading troops into that furnace was asking too much, so Graham rescheduled the attack for the next morning, leaving Campbell to endure another day’s wait.

Finally the assault began at 4.30 a.m. on the 25th, signalled by the explosion of the mine lodged in the drain. A small force of Portuguese soldiers rushed towards the hornwork to distract the French. Up ahead, in the gloom, Campbell could make out the leading British troops, the Royal Scots, climbing out of the trenches towards the breach. Unfortunately, the parallels that had been dug were so narrow they allowed only a few men out at a time. The French immediately opened fire.

The walls of San Sebastian were sturdily built and particularly well mortared, so rather than atomise the walls, the allied barrage had left great chunks of masonry scattered across the sands. ‘The space we had to traverse between this opening and the breach – some three hundred yards – was very rough, and broken by large pieces of rock, which the falling tide had left wet and exceedingly slippery’, explained Campbell.81 With the only light coming from the houses still burning in town, he and his men began to pick their way across the estuary, the stones and debris underfoot getting thicker as they approached the breach. The towers either side of the gap had been damaged by the bombardment, but still offered the enemy valuable cover from which to pick off the British.

The Royal Scots made it across first and as they neared the foot of the breach the fire from the enemy slackened encouragingly. In the lead were Major Frazer and Lieutenant Harry Jones of the Royal Engineers. They scrambled up the rubble pile but at the top found a sheer drop of nearly 15ft behind. The French had removed the steps up to the wall. ‘Follow me, my lads!’ shouted Frazer, and was promptly killed by a French musket ball. A handful of the Royals followed his lead but most stopped near the demi-bastion to return fire, taking cover among the debris.82

‘The whole distance to the breach, a space of some 300 yards, was so broken by rocks and stones covered with seaweed, and by deep pools of water, as to render it quite impossible in the dark for the men to preserve anything like the regularity of formation, exposed as they were at the time to heavy fire from the defences’, complained Cameron.83 The advance, according to Campbell, looked ‘more like one of individuals than that of a well-organised and disciplined military body’. Unless Campbell could maintain forward impetus, his men would be picked off where they were stood. He spurred them on as best he could, but as enemy rounds ricocheted off the boulders and kicked up the sand, the soldiers preferred to stay put. Meanwhile, troops were debouching from the British trenches, adding to the crowd huddled on the sands. Lieutenant Machel, the engineer accompanying the forlorn hope, already lay dead, so Campbell found Lieutenant Clarke, commander of the Royals’ light company, and suggested that together they might lead their men past the growing mob of petrified soldiers towards the breach, in the hope it might inspire them to follow. The words had scarcely left his mouth when Clarke fell dead in front of him.

Campbell collected up as many of his own men as he could find, along with Clarke’s company, and started forward, dodging the grenades hurled by the enemy, towards the breach. A handful of officers and men had reached this far only to be shot down. Campbell raced up the broken masonry towards the opening, but as he made it to the top he took a musket ball in the hip. Caught off balance, he tumbled back down.

Campbell tried moving his leg and to his relief found he could still walk. Nearby he noticed two officers of the Royals girding their men for another attempt. Campbell stood up gingerly, and hobbled over. The Royal Scots were glad of any extra officers they could find. As the blood poured from his hip, Campbell once again began to climb up the face of the breach.

This time the musket ball hit him on the inside of his left thigh.

![]()

At the foot of the breach Captain Archimbeau of the Royals urged his men on, ‘cheering and encouraging them forward in a very brave manner through all the interruptions’, but behind the bravado he knew the day was lost. The enemy showed no sign of flagging. On the contrary, they poured forth musket balls and grenades as ferociously as ever. Archimbeau reluctantly decided to pull back. As if in confirmation of the wisdom of his decision, a bullet hit him in the arm.

The Royal Scots started to withdraw, joined by the 38th Foot, who had turned back from the second breach further along the wall. Getting men out of the narrow trenches had proved so difficult that three companies of the 9th were only now emerging, in time to run straight into the retreating Royals and plunge both battalions into confusion. Colonel Cameron was irate. ‘Colonel Greville joined me there, and united his best efforts to mine to induce the Royals to return to their duty’, he wrote, ‘but we might as well have addressed ourselves to the horses … The forward officer and Staff all this while did not stir a leg out of the parallel!!’ ‘Seeing they would not return to their duty’, Cameron explained, ‘I endeavoured to pass with the 9th by the right, but the pressure from the front was so great, that I was immediately obliged to give it up.’84 The French fire intensified as the tide rose steadily. The general order to fall back rang out.

With the breach under heavy French fire, the injured were left behind. Lieutenant Jones,* wounded and unable to walk, could see enemy grenadiers emerging. ‘Oh, they are murdering us all!’ exclaimed one soldier, as they started finishing off the injured. Jones watched as a grenadier approached him, cutlass raised for the coup de grâce, but, at the last moment, a French sergeant stopped him in the act. ‘Oh, mon Colonel, êtes vous blessé’, he exclaimed. Jones’s elaborate blue engineer’s uniform had saved his life. He had been mistaken for a field officer and spared.85

Campbell was even luckier. Lying helpless at the foot of the breach, he had been rescued by Archimbeau’s men as they pulled back, and carried to his tent in the rear. Here he had to undergo an ordeal quite as daunting as battle: nineteenth-century surgery. In 1813 the prospects for a soldier with severe injuries were poor, especially when, as in Campbell’s case, those injuries were to body parts that could not be amputated. However, at least in the 9th Foot the prognosis was better than most. Throughout the Peninsular War the regiment lost remarkably few officers to wounds. Maybe it was because they employed more surgeons than average, maybe those surgeons were unusually skilled or perhaps they were just plain lucky, but for whatever reason, Campbell had a statistically higher chance of recovery in the 9th, especially at San Sebastian. ‘This climate is wonderfully healthy’, explained Gomm. ‘All our wounded recover faster here than they have been known to do elsewhere.’86

San Sebastian was Campbell’s sole combat defeat. Over his fifty-five year career he suffered a few draws, but never again withdrew from the field beaten. Campbell believed the reason for the failure of the assault lay in the decision to attack in darkness, coupled with the inability to mass the men ‘in one big honest lump’, as he put it. The mechanistic drilling of the troops, so effective in pitched battles in the open, had fallen to pieces in broken terrain. Whatever the reason behind it, the drubbing the British received on 25 July only enhanced Campbell’s reputation. He gained his second mention in despatches in just over a week, and had ninepence a day docked from his pay while hors de combat. Not for the last time, the sheer number of Colin Campbells* confused matters. ‘There is one thing I am sorry to see in the English Newspapers about a Lieutenant-Colonel Campbell, who is said to have behaved gallantly’, wrote Surgeon Dent to his cousin, ‘whereas there is no such Man here, and the praise bestowed on him is intended for a Lieutenant Colin Campbell of our regiment, who led the forlorn hope and was wounded in the breach.’87

Of the 2,000 troops who assaulted San Sebastian that day, 425 were killed, wounded or taken prisoner.88 Dishonour was heaped on dishonour when, two days later, the French launched a sortie and took a further 200 allied soldiers prisoner. ‘Instead of gaining laurels we sink deeper and deeper into disgrace every day’, complained Le Mesurier.89 Wellington’s response was to order a new attack.He called for 750 volunteers to ‘show the 5th Division how to mount a breach’. It was to be, in essence, a reworking of 25 July, though in daylight this time, with more men, and an even heavier bombardment beforehand to improve the odds. Graham’s guns had been fired until they were worn out but new ordnance arrived from England with plentiful ammunition and a company of sappers. It took time to deploy, but on 22 August the barrage began anew with seventy-three guns trained on San Sebastian.

Nine days later, the second infantry assault was launched. With extra guns, men and trenches, and troops able to see where they were going this time, more soldiers made it to the top, only to find an even greater drop down to the path behind. During the five-week intermission the French had filled the space with stakes, bits of furniture, railings, anything they could find that might make a soldier think twice before jumping. Ahead lay the old enemy in high dudgeon, behind the wrath of Wellington and national disgrace. Hunkering down in front of the breach seemed much the safest course, and soon the ground was thick with redcoats.

The allies threw everything they had into the fight, some 6,200 men,* but still the French did not weaken. As before, British troops massed in front of the breach, seemingly unable to manage the final few yards. Graham had no reserve troops left and the tide was on the rise, threatening to cut off his men. But then came a fierce, hot blast and a mighty thunderclap. ‘French soldiers near the spot were blown in the air, and fell singed and blackened in all directions.’90 A huge enemy magazine, packed with bombs and musket cartridges, had exploded. For a few seconds there was silence while the men lay insensible, dazed by the force of the discharge.91 It was the British who recovered first and, veiled by the smoke, stormed the breach. The battle had already lasted five hours but the allies conquered their weariness, and started brawling and bayoneting their way through the streets. With the town overrun, the garrison retreated into the castle (see Plate 6).

‘The whole town is ours’, wrote Colonel Frazer of the Royal Artillery, ‘and will very soon be nobody’s.’ Convention dictated that while the British did not pillage the countryside like the barbarian French, a town taken by storm was fair game. That said, it was supposed to be plundered systematically by prize agents, but since two-thirds of the officers had been killed or wounded there was little hope of maintaining order in the chaos. Within hours everything of value had been pocketed, smashed or set on fire. The looting only stopped when there was nothing left to steal, defile or desecrate. Soon the town was an inferno, thereby neatly destroying the evidence. Graham was unfazed: ‘I am quite sure that if Dover were in the hands of the French, and were taken by storm by a British army, the cellars and shops of the inhabitants would suffer as those of San Sebastian did.’92

Mount Orgullo remained with the enemy. ‘The French still hold the castle,’ wrote Gomm, ‘but they hold it like people that are anxious for an opportunity of surrendering with a good grace … there is little acharnement left among them.’93 After repeated cannonades, on 8 September they raised the white flag.

It had taken over 70,000 rounds of shot and shell to take San Sebastian.94 The British captured ninety-three guns, most so dilapidated that they were useless. It was victory, but victory tempered by the knowledge that, but for one lucky explosion, the result might have been very different. It was hard to take pride in a town won, in William Napier’s words, ‘by accident’.

![]()

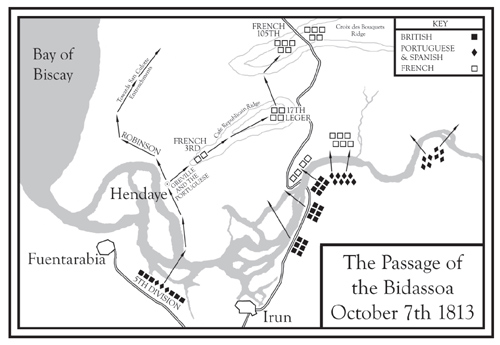

Campbell having sat out the second assault on 31 August, word reached him in early October that Wellington had a new offensive in the offing. Across Europe the emperor’s armies were in retreat. Bonaparte’s genius for battle seemed to have deserted him. It was time to start fighting Napoleon on his home turf. The Duc de Berri had already promised the allies 20,000 Royalist troops once they were on French soil. News that Austria too had joined forces with the allies convinced Wellington that the tide of events was with him. His target was the foothills of the Pyrenees, beyond the estuary of the River Bidassoa. ‘The heights on the right bank of the Bidassoa command such a view over us that we must have them,’ Wellington told Graham, ‘and the sooner the better.’95

Two months had passed and Campbell was still waiting for his captaincy. Wellington had publicly laid the blame for the failure on 25 July on the men at the breach. It was hard to condemn an assault and at the same time promote the man who’d been at the centre of it. Campbell needed a way of reminding him of his talents. So, with another wounded officer, he put on his uniform, strapped his sword to his side and headed for Wellington’s army massing 10 miles up the coast.

The Bidassoa wound its lazy way down from the Pyrenees through a fertile valley of fruit trees and apple orchards, before widening as it reached the sea a few miles up the coast from San Sebastian. Soult realised its strategic importance and had fortified the French lines on the east bank along a 23-mile front. In his mind the strip nearest the coast, beside the estuary, would be the hardest to cross, so he ordered Reille to leave just one division there. Reille’s other division was stationed 5 miles behind the French lines at Boyer, as a reserve. Soult had an additional 8,000 men about 12 miles from the estuary, ready to deploy in support.

The 5th Division, including the 1/9th, were camped west of the Bidassoa, near Oyarzum. To get there Campbell cadged lifts on commissariat carts. He reached his colleagues on 6 October. The 1/9th were about to move off. Wellington’s big push was scheduled for the following morning. Discharging himself from his sickbed without permission invited a court martial, but Colonel Cameron limited the punishment to the lightest of sanctions, a severe reprimand, before putting Campbell back in command of the light company which, once again, would lead the battalion’s assault.

Wellington planned to launch into his enemy along a 4-mile front, leading inland from the sea, precisely where Soult least expected it. Wellington had gleaned from the locals that at Irun and Fuenterabia the river was fordable at low tide. It was here the British would cross. That night Campbell led his company the short distance from their camp towards Fuenterabia, the noise of the marching column helpfully muffled by a thunderstorm. By the time they reached their destination, the rain had eased and the night became sultry and close. Except for a few casinos kept open for the troops, Fuenterabia had been abandoned.96 Campbell’s company bivouacked in the deserted buildings to keep their arrival a secret from the French on the bank opposite. They had left their tents standing at Oyarzum for the same reason.97

Campbell was to cross the estuary and then swing right to threaten the flank of the enemy opposing the British soldiers crossing at Irun. In the small hours he led his men down to a ditch next to the river, obscured by a tall turf bank. At 7 a.m. a bugle from the steeple at Fuenterabia sounded the advance and the 1/9th started forward at the head of the right-hand column under Colonel Greville. Major-General Robinson’s brigade took the left, with the Portuguese in the centre. In front of his light company, at the front of the 9th, Campbell reached the sands first and waded into the water. The tide was powerful, and the muddy bottom made it slow going. It was now that his men were at their most vulnerable. Reloading a musket in 3ft of water was nigh on impossible and if a soldier got his musket or cartouche of cartridges wet he would be unable to fire it at all. Further upstream Campbell could hear distant gunfire as the engagement at Irun began, but opposite Fuenterabia the French remained silent.

Campbell reached the far shore without incident but, as his men were forming up, the enemy let fly with musket and gun.98 Though short on troops, the French had the advantage of higher ground. Campbell’s first obstacle was Hendaye, ‘a miserable and nearly ruined village’, according to one Guards officer, ‘deserted before by all but a few fishermen’.99 Its handful of enemy soldiers was put to flight by a charge from the 9th. As the battalion made its way up the Café Republicain ridge, the 9th met more determined resistance from the French 3rd and 17th regiments but the enemy here too was forced back, leaving the way clear to the heights of Croix des Bouquets. On this ridge the French were more firmly entrenched and fortified with artillery. Reille knew that if he could dig his heels in and wait for his reserve troops from Boyer, he might just prevail.

Instead of the traditional advance in line, Greville told Cameron to go forward in echelon, staggering his force. He swiftly gained the northern slope of the ridge, before turning to attack the French flank. In the way stood a substantial redoubt discharging a murderous fire, but, shrugging off heavy casualties, the 9th stormed it.100 Cameron re-formed his by now disordered battalion and advanced along the ridge towards a battalion of the French 105th Regiment. Shouting furiously, the 9th charged, but the French ‘stood their ground till we came within nine or ten yards of them, when they made off with great speed. In this advance we suffered very severely from the enemy’s fire, as they were posted in column and in great numbers, the ground on which they were formed sloping inwards, this giving them a great advantage in firing upwards’, recalled Cameron. ‘It was one of the hottest fires I was ever in. Ten or eleven officers were severely wounded and about seventy men placed hors de combat.’101 Still suffering from the two bullet wounds he had received in July, Campbell had been shot again.102 Bleeding and exhausted, but content that the French were falling back on Urrogne, he watched as a figure in a grey frock coat, wearing a cocked hat with oilskin cover, approached. All around the men started to cheer. Wellington stopped and thanked them for their efforts and then rode off.103

* A captain normally commanded a company, but with Captain Alexander Campbell dead and Captain Gomm doing staff work, the 9th was a bit short.

** Currently in the National Museum of Scotland, it can be seen at his side in the portrait by Sir Francis Grant completed shortly before his death (Institute of Directors, Pall Mall, London) and on his statue in Glasgow.

* Hanoverian troops who formed a foreign corps within the British army.

* Though Blakeney describes the retreat as being in column, Beamish, Henegan and Fortescue all describe forming square and the defence by the King’s German Legion.

* Gough would see battle with Campbell in China and India, eventually gaining a field marshal’s baton and a viscountcy. He gave the eulogy at Campbell’s funeral. The Napoleonic eagle was Bonaparte’s attempt to ape the aquila of ancient Rome. The eagle formed a grand finial to the pole supporting the French colours. The captured eagle was paraded at Horse Guards with full pomp in May 1811 and then displayed in the Royal Hospital Chelsea, where it was joined by twelve more. It was stolen in April 1852. Inevitably suspicion fell on the French, but its fate remains a mystery.

* This is according to his service record of 1829. It states that in late 1812 he was present at ‘the affairs of Coin and Alhaurin’ and acted as ADC. However, the same document records his service in Tarragona as being in 1812 rather than 1811. The French had evacuated Andalucia by early August 1812, while Ballesteros had taken Malaga that July before being removed from command in November 1812, making Campbell’s service as ADC in the autumn of 1811 far more likely. ‘Livesay’ may have been Brigadier-General Luis de Lacy (1772–1817).

** This did not stop Campbell alluding proudly to his service at the Siege of Tarifa in various documents.

*** ‘What the devil is the use of making me a Marquess?’ Wellington said upon hearing of his new title (Holmes, 169).

* French armies were named after their intended theatre of operations, e.g. the Armée d’Angleterre prepared for the invasion of England.

** Campbell recorded it as 5 p.m. and Wellington’s ADCs as 3 p.m., but Wellington’s actual instructions are marked 2 p.m. (Wellington, VI, 538; Stanhope, 115).

*** Dent blames this on the decision to advance in column instead of in line, allowing the enemy artillery to wreak havoc (35).

* This was literally true after the fall of Mooltan in the Second Sikh War, where soldiers could scarcely walk after they crammed their boots with gold to smuggle it past the prize agents (see Chapter 5).

* The same tactic used to take the town in 1719.

** Squat, short-range iron cannons.

*** An outwork of half-moon shape. Cameron refers to both the lunette and the Cask Redoubt as ‘the redoubt’, but one can determine which he means from the succession of events.

* Campbell may have been encouraged by Colonel Cameron, who won his captaincy after storming the Fort Fleur d’Épée in Guadeloupe in 1793.

* Campbell met up again with Jones when he took over as senior engineer in the Crimea.

* The Army List of 1813 includes thirteen officers called Colin Campbell.

** This compares with only three battalions sent in on 25 July, around one-third the number (Oman, VII, 35–6).

1 Oman, IV, 96; Brett-James, General Graham, 34.

2 PRO/WO/1/225/121.

3 Blakeney, 180.

4 Brett-James, General Graham, 201.

5 Stanhope, 47.

6 Blakeney, 183; Fortescue, VIII, 50; Henegan, I, 208–9.

7 Blakeney, 184.

8 Brett-James, General Graham, 208; Fortescue, VIII, 50.

9 Fortescue, VIII, 49.

10 Blakeney, 185.

11 Bunbury, I, 74.

12 Henegan, I, 210

13 Blakeney, 187; Glover, The Peninsular War, 124.

14 Brett-James, General Graham, 210.

15 Loraine Petre, I, 216; Cadell, 102; Oman VIII, 114.

16 Blakeney, 189.

17 Fortescue, VIII, 55.

18 Stanhope, 49.

19 Blakeney, 196; Fortescue, VIII, 61.

20 Kinglake, III, 132.

21 Shadwell, I,10.

22 Henegan, I, 220.

23 Hall, C., 175, Dent, 26; Codrington, I, 228.

24 Fortescue, VIII, 247.

25 Fortescue VIII/244 & PRO/WO/1/225/181.

26 PRO/WO/1/225/213-15.

27 Fortescue, VIII, 335.

28 Shadwell, I, 11; Loraine Petre, I, 217; Hale, 101.

29 Fortescue, IX, 524.

30 Gomm, 301.

31 Dent, 33; Oman, VI, 322; Gomm, 299.

32 RNRM/45.4.

33 Loraine Petre, I, 245.

34 Stanhope, 112; Hayward, 65; Bridgeman, 113.

35 Glover, The Peninsular War, 28.

36 Fitzclarence, 107.

37 Gomm, 306.

38 Sherer, 236.

39 RNRM/45.4.

40 Hale, 102; Oman, V, 374.

41 Shadwell, I, 13.

42 Hale, 102.

43 Shadwell, I, 14.

44 Dickson, 912.

45 RNRM/45.4.

46 Hale, 103.

47 Hale, 104.

48 Shadwell, I, 15.

49 RNRM/45.4.

50 Hale, 105; Loraine Petre, I, 249.

51 Hale, 105.

52 Shadwell, I, 16.

53 Hale, 106.

54 Shadwell, I, 16; Stanhope, 116.

55 Gomm, 305.

56 Stanhope, 117.

57 Loraine Petre, I, 250.

58 Hale, 107.

59 Oman, VI, 441.

60 Stanhope, 117.

61 Harries-Jenkins, 8.

62 Hennell, 103.

63 Bell, G., 89.

64 WIG/EHC25/M793/176.

65 RNRM/45.4.

66 Shadwell, I, 120.

67 Dent, 37; WIG/EHC25/M793/176.

68 Loraine Petre, I, 253; Hale, 114.

69 Gomm, 317.

70 Jones, J., II, 16–17.

71 Jones, J., II, 21; Shadwell, I, 20.

72 Loraine Petre, I, 254; RNRM/45.9.1.

73 RNRM/45.1.1; 45.1.2.

74 RNRM/45.1.1; WIG/EHC25/M793/182.

75 RNRM/45.1.1.

76 RNRM/45.1.1.

77 Shadwell, I, 22–3.

78 Wrottesley, I, 267; Jones, J., II, 32.

79 Shadwell, I, 25.

80 Dent, 39; Shadwell, I, 23; Wrottesley, I, 269.

81 Shadwell, I, 25.

82 Stanhope, 122; Henegan, II, 44; RNRM/45.9.1.

83 RNRM/45.9.1.

84 RNRM/45.9.1.

85 Jones, H., 193.

86 Gomm, 322.

87 Dent, 39.

88 Loraine Petre, I, 258.

89 WIG/EHC25/M793/184.

90 Cooke, II, 14.

91 Gleig, 54.

92 Brett-James, General Graham, 281.

93 Gomm, 318–19.

94 Jones, J., II, 91.

95 Beatson, 59.

96 Gleig, 82.

97 Beatson, 67.

98 RNRM/45.9.

99 Malmesbury, II, 386.

100 Beatson, 78.

101 RNRM/45.9.

102 Ryan, 81.

103 Frazer, 292; Beatson, 81.