‘It is a remarkable expedition, and [we] will have many historians to record our exploits, and recount our success or failure. The latter I think scarcely possible; but there is always a chance of it; and if that chance should turn against us, the memory of the defeat will be stamped in such characters of blood as will put half of England in mourning’

Major Sterling, brigade major to Sir Colin Campbell

‘We went to war not so much to keep the Sultan and the Muslims in Turkey, as to keep the Russians out of it’,1 claimed Palmerston – or, as Sellar and Yeatman put it, because the British had yet to fight the Russians and because Russia was too big and pointing in the direction of India. Or perhaps it had simply been too long since the last war. As Fortescue wrote, ‘a generation had sprung up in England, as in France, which knew nothing of war and desired to try its mettle by experience’.2

War had been sparked by a dispute over who protected the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, situated in Islamic, Ottoman territory: the French on behalf of the Roman Catholics or Tsar Nicholas for the Russian Orthodox Church. Catholic attempts in June 1853 to fix their own star over the manger resulted in a riot and the murder of several Orthodox priests, giving the tsar the excuse he needed to pounce. That July, Russia invaded Turkey’s Danubian principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia. After vacillating for months, Britain and France finally declared war on 28 March 1854, by which time preparations to despatch troops eastwards were well in hand.

The British traditionally launch major wars half-furnished. This was doubly true in 1854. Four decades of peace in Europe had left the army pared to the bone. The commander-in-chief struggled with a staff of eleven. The Woolwich arsenal was so stretched it had been unable to provide the seventeen guns requested for the Duke of Wellington’s state funeral in 1852. Since Waterloo, military methodology had likewise atrophied. For the war with Russia, the quartermaster-general’s department simply reprinted Sir George Murray’s instructions used in the Peninsular War. Responsibilities were still split between competing beadledoms. Political control was divided between the Home Secretary (troops in the UK) and the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies (troops abroad), while the Secretary of State at War did the bookkeeping. The commander-in-chief only commanded those soldiers in Britain, yet was liable for the distribution and deployment of the army throughout the empire. A separate Board of Ordnance organised ammunition, guns, muskets, fortifications and barracks, and directed the Royal Artillery and Royal Engineers. The Commissariat, a civil authority answerable to the Treasury, provided rations and supplies. Although the Commissariat provided the load, responsibility for the vehicle lay with the Quartermaster’s Department. To complicate things further, there was the Army Medical Department, the Audit Office, the Paymaster-General’s Office, the Commissioners of the Chelsea Hospital, a board for the inspection of clothing, and the Admiralty’s Transport Office (providing passage for troops and supplies overseas), all acting as independent bodies.

The troops were in just as parlous a state as the administration. Despite the vogue for do-goodery, the rank and file were still neglected. Although barracks had slowly improved, accommodation was still more cramped than for a convict and mortality rates for soldiers outstripped those of the general population. Above all, the men lacked experience in the field. Even experience on exercise was slight. Until 1852 guardsmen were allowed just thirty musket rounds each, every three years, for target practice.3 ‘Our soldiers were magnificent fighting material: no better have ever pulled a trigger in any war’, claimed Field Marshal Garnet Wolseley, but:

it was not a ‘going military machine’ any more than a steam engine is whose boiler is in Halifax, its cylinder in China, and its other machinery distributed in bits wherever the map of the world is coloured red, and for which machine neither water nor coals nor oil nor repairing tools are kept at hand.4

‘The campaign was thus being commenced with a frivolity excusable only by the novelty of a great war’, sniffed Count von Eckstaedt, Saxony’s ambassador in London.5

Directing the campaign was Wellington’s erstwhile ADC and long-time military secretary at Horse Guards, Lord Raglan (formerly Lord Fitzroy Somerset; see Plate 13). No one could claim more experience of army bureaucracy, but the 65-year-old Raglan, in Woodham Smith’s words an ‘extraordinary blend of suavity, charm, aristocratic prejudice and marble indifference’,6 had never commanded troops in the field. ‘He was dignified, brave, courteous, gentle and honourable to the point of saintliness’, added Barnett. ‘Unfortunately these virtues do not make for success or survival in a tough world.’7

Commander-in-Chief Lord Hardinge offered Campbell a brigade command in the expedition, subject to Raglan’s approval. A rector’s son, Hardinge endorsed promotion by merit, and had been impressed by Campbell’s conduct in Ireland and India. Resignation in Peshawur might have branded Campbell a troublemaker, but for the men in Whitehall there was no especial danger in granting him a brigade. The war would be over before he progressed far enough up the ranks to do any real harm.

Campbell met Raglan to confirm the appointment, but Raglan was evasive, saying he had yet to be confirmed as leader of the expeditionary force. ‘His manner, though civil, was far more serious than usual’, remarked Campbell. ‘He did not say whether he would accept the command or not.’8 For two days Campbell waited. The government was divided: the Secretary for War, the Duke of Newcastle, questioned Raglan’s abilities, but once the queen expressed her support, the cabinet concurred. Raglan was confirmed as commander-in-chief for the campaign and so, on 21 February 1854, Campbell was gazetted with the local rank of brigadier-general. A few days later an invitation arrived for dinner with the queen.

‘I am very much pleased with my appointment to the Command of a Brigade in this expedition. It is to consist of the 28th, 33rd and 50th Regts., all good Corps’, he told Seward:

The impression in the public mind is that this combined force is to occupy some position between Adrianople and Constantinople for the protection of the latter. While its presence there would give moral support to the Turkish Army on the Danube, I cannot myself believe that the services of a force of between 60 and 70,000 French and English troops, are to be confined to an object so limited.

He was sure Raglan’s ambitions would broaden:

The weak points of Russia in that part of the world are the ports she holds on the Black Sea, and these I should think we shall attempt to destroy … But these are mere rumours, for no one really knows in what manner it is intended to employ us.9

Campbell chose Captain Shadwell, who had served with him in India, as aide-de-camp, and Captain Anthony Sterling as his brigade major. The son of Edward Sterling, leader writer for The Times, Anthony had grown up in the company of journalists and liberals. In this, the first British war fought under the unblinking gaze of the media,* he would be acting as public relations officer long before the term had been invented.

Sterling shared Campbell’s conception of the officer ideal. ‘It is not flaunting about in a red coat which makes the officer’, he asserted. ‘It is the earnest attention to every minute and tiresome detail connected with the soldiers’ welfare.’ A broad vein of radicalism ran through his politics. ‘The miserable way in which the aristocracy have managed matters shows that they have no particular right to govern’, wrote Sterling. ‘I hate a Republic, yet cannot feel contented under the rule of foolish lords.’ By the standards of the times, his views were extreme; he was even in favour of a woman prime minister or commander-in-chief.10 More significantly, Sterling was more than just a sympathetic, liberally-minded officer. He was Campbell’s cousin.11

Campbell took family loyalty very seriously. Edward Sterling had become embroiled in a feud with choleric Bath MP John Roebuck after one of the latter’s 1835 Pamphlets for the People was rubbished by a Times editorial that labelled its author ‘as ill-informed as he is ill-bred’, a ‘rabid little reviler’ who should ‘sink into the mud of his own insignificance’. Roebuck hit back by devoting his next pamphlet, The Stamped Press of London and its Morality, to the vices of newsmen. Hackles up, he then challenged Edward to a duel.

‘It was with aversion and dislike that I mixed myself up with disputes and quarrels in my position as commanding officer of a corps,’ wrote Campbell, ‘and still more so with persons hotly engaged in political controversies, from which a soldier ought to keep as far aloof as he would from treason’,12 but nevertheless he agreed to act as Sterling’s second. Underneath an infinitely more measured leader article about Roebuck on 29 June 1835, The Times, at Campbell’s request, reprinted Roebuck’s accusations of Sterling’s cowardice, baseness, skulking, dishonesty, charlatanism in society, selling himself to the Tory party and ‘a degree of depravity worse than that of an assassin’. At the same time, Sterling denied that the barbed editorials were his work, brazenly claiming that he had ‘never been technically and morally connected with the editorship of The Times’. In fact, he had been a staff writer since 1813 and his work as a leader writer was an open secret, especially among his fellow club members at Brooks.13

Somehow Campbell soothed Roebuck into accepting Sterling’s denial, withdrawing his accusations completely and apologising publicly, all with a magnanimity which elevated him in Campbell’s estimation considerably. It was one of those strange quirks of fate that on the sole occasion Campbell had a brush with a backbencher, it was with a man who went on to bring down the government over its direction of the Crimean War and became inquisitor-in-chief in the ensuing enquiry.

![]()

‘I am to embark today at Woolwich at 12 o’clock on board the Touring steamer which is to convey officers of the staff and their horses to Gallipolli, touching at Gibraltar and Malta for coal and water’, Campbell told Seward on 3 April. ‘The final organisation of the force into Brigades and Divisions will not take place until the arrival of Lord Raglan … when the whole of the troops will have reached Turkey.’14

Having disembarked on 2 May, as expected Raglan restructured his army, giving Campbell the Highland Brigade of the 1st Division: the 42nd (Black Watch), 79th (Cameron Highlanders) and 93rd Foot (Sutherland Highlanders). In truth, Campbell’s ‘Highlanders’ were more often plucked from the streets of Glasgow than from the glens.15 By 1854 the Highland clearances and the Scottish potato famine of the late 1840s had left an embittered community, thinned by evictions and mass migration and reluctant to fight for the queen. When the Duke of Sutherland arrived in Golspie to recruit men for the 93rd, one local told his Grace, ‘should the Tsar of Russia take possession of Dunrobin Castle and of Stafford House … we couldn’t expect worse treatment at his hands than we have experienced at the hands of your family for the last fifty years’.16 That said, whether from town or countryside, the men still maintained a distinctly Highland esprit de corps.

Campbell ranked with brigade commanders in every instance younger than him. To say he had fought more battles than all the others put together is no exaggeration.* The 3rd Battalion Grenadier Guards, 1st Battalion Coldstream Guards and 1st Battalion Scots Fusilier Guards formed the senior brigade in the 1st Division, under the command of Henry Bentinck – like so many generals in the Crimea, a man with no experience of war. ‘In any other division I should have been the senior brigadier-general’, complained Campbell.17 Guards officers still enjoyed the privilege of double rank,** so although Bentinck had only been a lieutenant-colonel in the regiment since 22 August 1851 (by which time Campbell had been a lieutenant-colonel for eighteen years), he had been a colonel in the army from 28 November 1841 (a year and a month before Campbell), putting him ten places ahead on the Army List.18

The extent to which birth still counted in the British army was made abundantly clear by Raglan’s choice of the Duke of Cambridge (grandson of George III and first cousin of Queen Victoria) as Campbell’s immediate senior and commander of the 1st Division. Colonel aged 9 and major-general at 26, Cambridge had already commanded the 17th Lancers and been Inspector-General of Cavalry, but he had never seen action. He was undeniably likeable and good-natured, but his sensitive side militated against battlefield command. At 35, he was the youngest divisional general by a quarter of a century, though baldness, gout, corpulence and a luxuriant beard left him looking older than his years.

The background of the generals was almost universally grand,* even though the supremacy of pedigree over talent was no longer axiomatic. ‘It seemed either that Lord Raglan did not expect war, and so gave places to anyone who had influence,’ wrote the iconoclastic Sterling, ‘or, if he did expect war, he intended to do all the work himself.’19 One colonel complained, ‘We suffer from two varieties [of general], principally the one I may call the Gentlemanly helpless variety; the other variety are given up to leathern “stocks” and foul language, and tho’ I personally prefer the former, I really think the latter do more work & good.’20

By 25 April, Campbell had reached Constantinople and set up headquarters in the imposing Turkish barracks at Scutari. The first of his battalions, the 93rd, arrived on 9 May, followed by the 79th on 20 May, and on 7 June, the 42nd. Campbell imposed a strict training regimen:

One lieutenant wrote:

At about 4 am every morning we got up to parade and drill which lasted about two hours, but three or four times a week we had to march seven or eight miles over very rough country and indulge in sham fights, skirmishes and retreats for the gratification of HRH and Sir Colin Campbell. However, after 8 am we had the day to ourselves.21

The 93rd had already been issued with 250 state-of-the-art Minié rifles, and soon the rest of Campbell’s brigade received them too. The new weapon used an elongated bullet narrow enough to be dropped, rather than rammed, down the barrel. When fired, the bullet expanded into the rifling. At 150 yards it was twice as accurate as the old smoothbore musket, at a stroke transforming every infantry soldier into a rifleman. Its range promised superiority for the infantry over the cavalry at last. Sir Charles Napier, however, had been unimpressed, warning that the Minié would ‘destroy that intrepid spirit which makes the British soldier always dash at his enemy’. The more ossified corps reacted with equal disdain. When asked for someone to familiarise himself with the new rifle at the Hythe school of musketry, the 90th Foot sent a one-armed officer.22

Within days of the Black Watch’s arrival, Campbell’s brigade sailed for Varna** on the Bulgarian coast, from where Raglan planned to help the Turks at Silistria, currently besieged by the Russians. Having encamped a mile south of the town, the division moved further inland to Aladeen on 1 July. Here the detritus of the old Light Division camp, ‘dried leaves, broken bottles, battered cooking tins, huge half-burnt stakes, fowls’ heads, fragments of London papers, and impromptu musket racks cumber the ground in all directions’.23 Campbell instituted basic hygiene measures, such as designating certain springs for drinking water and others for watering horses and washing, but by late July cholera had broken out among the Guards. The division moved 3 miles away to the little village of Gevreklek, hoping to leave the disease behind, but by 1 August a soldier from the 42nd had died. The next day Campbell issued cholera belts*** but a week later nearly one-sixth of the division was incapacitated by cholera, dysentery, fever and diarrhoea. Having lost fifteen men of the 93rd, Campbell segregated the regiment in a new location, 2 miles away, but by 18 August 300 of his brigade were still afflicted.

While his Highlanders were sickening, the motive to stay in Bulgaria had already disappeared. The Turks had raised the siege of Silistria by themselves and were busy chasing the Russians back to the Danube. With the tsar humbled and Turkish territory restored, the allies’ war aims had been achieved, but the war had never been about fighting for Turkey, rather against Russia, so the Duke of Newcastle (Secretary of State for War) told Raglan that the cabinet wanted Sebastopol, the Crimean home port of the Russian Black Sea Fleet, destroyed. ‘The broad policy of the war consists in striking at the very heart of the Russian power in the East, and that heart is at Sebastopol’, explained The Times on 24 July 1854. Generals Burgoyne and Tylden, and the Duke of Cambridge warned Raglan that it was too late in the year to start campaigning, especially given the disease crippling the troops, but, as the duke recorded in his diary, ‘public opinion in England is to be satisfied at any hazard, and so the attempt is to be made’.24

Wracked with illness and short of supplies, Campbell’s Highlanders marched to Varna, ready to sail for the Crimea. ‘We are wild with delight at the prospect of being shot at, instead of dying of cholera!’ wrote one Guards officer, in an echo of the sentiments of Corunna.25 On 29 August Campbell’s brigade embarked. The allies’ ships mustered in Baltchik Bay and on 7 September set sail for Russia, with 61,400 men and 132 guns on board.26 Three days later the fleet anchored off the Crimean coast, a vast crescent of vessels 1½ miles deep, and 9 miles from point to point. ‘There has not been such an expedition from England since that unfortunate one under Lord Chatham’, observed Sterling, ominously.27 The British had set out with a comparable lack of intelligence. ‘Success or failure depends entirely on the force the enemy may have in the country,’ admitted General Burgoyne, ‘of which we have no information whatever’.28 Scarcely any of the officers even had maps. ‘They would have been great service’, confessed Lord Wantage of the Guards. ‘Sir Colin Campbell has got one and shows it as a great favour to his friends.’29

Only now, after surveying the coast, did Raglan decide on Calamita Bay, a little north of Sebastopol, as the landing ground. Despite minute instructions and the sailors’ best efforts, the landing on 14 September was shambolic. To reduce weight, each soldier was ordered to leave his knapsack behind but instructed to take boots, socks, shirt and forage cap, wrapped in a blanket and greatcoat, along with three days’ rations, sixty rounds of ammunition and a canteen.* Very little else was provided. ‘No army ever took the field, or landed in a hostile country … so unprepared and so imperfectly supplied with medical and surgical equipment’, complained Surgeon Munro of the 93rd.30 Cholera was still rife. Nine men, three sergeants and a corporal of the 93rd had died on the short voyage and the 79th lost four men that first night. Without tents, Campbell’s brigade had to bivouac a few miles inland near Lake Touzla. It was a foul night to be out in the open. ‘My comrade and I’, wrote Private Cameron of the 93rd, ‘got grass and anything we could gather for a bed and laid down, having a stone for a pillow, and then the rain came pouring on us. So we lay on our backs holding up our blankets with our hands so as the rain would run down both sides, and so keep our firelocks and ammunition dry.’31 ‘Our party were, I imagine, the only people who had a tent the first night’,32 confessed Sterling, who had brought his own.

Next morning the men laid out their topcoats and blankets to dry while the tents were landed. For five days supplies were brought ashore, while the quartermasters negotiated for food and transport with the locals, with limited success. Worried that forage might be scarce, Commissary-General William Filder had ordered that virtually every horse and mule be left behind in Varna. Lacking the pack animals or wagons to carry them, almost all the tents and hospital marquees now had to be returned to the ships. Campbell was allowed one tent for himself, one for his staff, and three for his brigade’s sick and wounded.

On 19 September the allies began their advance. ‘The ground we traversed was a succession of arid, barren-looking downs, covered knee deep with rank dried weeds and thistles, which made walking always laborious, and sometimes painful’, complained the Morning Herald’s correspondent. ‘The grass quite swarmed with snakes and centipedes, and hundreds of the former were killed.’33 At about 3.30 p.m. they reached the paltry trickle known as the Bulganak River. ‘You should have seen those poor thirsty fellows drinking up that dirty puddle as if it had been nectar,’ recalled one soldier.34 Campbell halted his brigade, and made sure they filled their canteens in rotation to avoid churning the stream to mud. Meanwhile, Raglan sent Lord Cardigan’s Light Brigade across the Bulganak to scout the ground ahead. Raglan’s staff officers enjoyed taunting the cavalry,**35 so when Cardigan found 2,000 Russian troopers in his path he was keen to prove his corps. What Cardigan could not see was 6,000 more Russian infantry, artillery, cavalry and Cossacks beyond. Fortunately, Raglan spotted them in time and ordered Cardigan to retire, though not before the Russian artillery had cost him four casualties. One trooper returned with his foot ‘dangling by a piece of skin’.36

South lay the River Alma, flowing westwards to the sea, transforming the dry plain into a lush valley. The approach from the north was uninteresting; a gentle slope down to the river, dotted with vineyards and orchards, reminiscent of the Iberian Peninsula of Campbell’s teens. In terrible contrast, the south bank was a natural fortress. At the estuary it rose up to cliffs 350ft high, and inland formed a stone eyrie criss-crossed with ridges. It was here that the Russians had lodged their army. As the British halted before the Alma at noon the next day, the magnitude of the task facing them was clear. ‘The greatest novice living could see that it was a fearful thing to undertake’, wrote one lancer.37

Commanding the Russians was Prince Menschikoff, a man who had fought Napoleon out of Russia and been castrated by a cannonball for his pains. On hearing of the approach of the allied fleet on 13 September, Menschikoff had positioned 40,000 soldiers on the rugged heights above the Alma, reasoning that he had a better chance of defeating enemy troops here than on the beaches where they enjoyed the protection of their own navies. His men had cleared the undergrowth near the river to deny the allied skirmishers cover, and staked the hillside with white range markers for their artillery. Altogether the Russians fielded ninety-six guns, nearly 4,000 cavalrymen and thirty-six infantry battalions against the allies’ twenty-seven.38

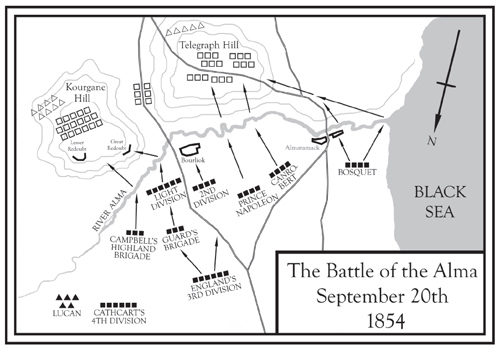

The road to Sebastopol led south, past the village of Bourliok and over the Alma, wending its way between Kourgane Hill on the left and a second rise on the right, where the Russians were building a telegraph tower ringed by a low parapet armed with field guns. On the northern slope of Kourgane Hill were two Russian earthwork fortifications; to the west, the Great Redoubt, a 300-yard trench with a parapet heaped up on both sides and armed with twelve heavy guns, commanding the ground down to the river and the Sebastopol Road; and to the east, the Lesser Redoubt, sporting eight guns, protecting the Russian right flank and the flank of its greater brother.39 Menschikoff was confident of his position. If the allies advanced head-on or towards his eastward flank they would be attacking uphill against well-entrenched artillery and superior cavalry, and to the west he had the barrier of the cliffs to shield him.

Raglan and French commander Marshal Saint-Arnaud agreed that General Bosquet would head towards the estuary to turn the Russian left flank, while more French divisions under General Canrobert and Prince Napoleon would assault Telegraph Hill. The British Light Division, supported by Bentinck’s Guards and Campbell’s Highlanders, would, as one captain put it, take ‘the bull by the horns, Lord Gough fashion, and march straight up to the batteries’ on Kourgane Hill.40 Behind them would be the 4th Division as a reserve. To the left and somewhat back, the Earl of Lucan’s cavalry would wait, protecting the British flank, ready to exploit any Russian weakness. To the right, the 2nd Division would head for Bourliok, supported by the 3rd Division.

Immediately the Light Division had started forward around 1 p.m., Campbell noticed it was marching at a slight angle, every step drawing it closer to the 2nd Division on its right. The 2nd Division was in turn being crushed on its right by the French. The two British divisions began to overlap, bringing the end of the 2nd Division into the line of fire of the right-hand battery of the Light Division. Raglan sent an order to its commander, Sir George Brown, to move to his left. Nothing happened. Raglan rode down to give the order in person, but Brown could not be found and, anxious not to offend the notoriously touchy general by leaving the order with his subordinate, Raglan instead instructed the Duke of Cambridge to deploy his two brigades on a wider front. This left no room for the 3rd Division under Sir Richard England on the duke’s right, so Raglan ordered England to re-form behind the 1st Division.

As the British neared the river, the Russian artillery opened a blistering onslaught. ‘Their guns were of large calibre’, explained Campbell, ‘and quite overpowered the fire of our 9 pounders.’41 Raglan ordered the men of the leading divisions to lie down. Carrying away the wounded was a tempting excuse to escape the Russian fire, but Campbell had warned his men that ‘Whoever is wounded must lie where he is until a bandsman comes to attend to him; I don’t care what rank he is. No soldiers must go carrying off wounded men. If any soldier does such a thing, his name shall be stuck up in his parish church.’42

The British were waiting upon the French to their right. By 2 p.m. Bosquet had taken the village of Almatamack unopposed and crossed the river. Soon French artillery was rattling along the road leading up to the plateau beyond, while Zouaves* swarmed up the heights. As General Kiriakoff deployed two Russian battalions plus artillery on the eastern slopes of Telegraph Hill to repel the French, Menschikoff rode over with seven more infantry battalions, four squadrons of Hussars and four gun batteries. The Russian artillery was surprised to find its fire returned by French guns which had already reached the plateau. Shaken, Menschikoff pulled his men back while Bosquet halted awaiting reinforcements.

Canrobert’s and Prince Napoleon’s divisions had been advancing in a line between the village of Bourliok to the east and Almatamack to the west. Once across the river, Canrobert pressed on south towards Telegraph Hill but, in the face of the Russian guns, Prince Napoleon’s division halted. Canrobert now stopped too, waiting for his artillery to catch up and give him covering fire. Saint-Arnaud sent two further brigades in support but both halted below Telegraph Hill with their colleagues. Now both allied armies were pinned down in the lee of each hill, with the Russian gunners above steadily knocking them down like nine pins. The only general who had gained any commanding ground was Bosquet, and his hold on it was tenuous. Desperate to maintain momentum, Raglan ordered his divisions to stand and march.

Ahead of Campbell were the two brigades of Brown’s Light Division, under Generals Buller and Codrington. Having made it across the Alma, Buller had halted to protect the British flank. Codrington’s men had reached the far bank in a disorganised mob but their commander decided straightaway to press on up the hill towards the Great Redoubt. ‘All being so eager to get at the Russians, we never waited to form line properly, but up the embankment we went in great disorder’, recollected one sergeant.43 ‘By God! Those regiments are not moving like English soldiers’, declared Campbell.44 ‘Instantly grape and canister poured through and through them, sweeping down whole sections at a time’, recalled one artillery officer.45 Two blocks of Russian infantry stood either side of the Great Redoubt to funnel the Light Division in front of the guns. As Codrington’s men closed in, Russian general Prince Gorchakoff ordered these men to advance. Mild fire from the British sent the enemy column to the east into retreat, while the other column, encountering heavy resistance from the 7th Royal Fusiliers under Colonel Lacy Yea, stopped and threw out skirmishers.

As Codrington neared the Great Redoubt the enemy guns fell silent. Through the smoke, the Russians could be glimpsed removing their artillery. The British swarmed up fast enough to capture two guns before the enemy could extricate them, but the rest escaped. Codrington desperately needed reinforcements to secure the entrenchment, but Cambridge’s 1st Division was still the wrong side of the river, halted in front of the vineyards which lined the riverbank. Unused to battle, the duke was scared of making a mistake. Raglan’s quartermaster-general, Airey, rode over and told Bentinck, brigade commander of the Guards, to advance. ‘Must we always keep within three hundred yards of the Light Division?’ he replied, dryly. At this point Airey caught sight of the duke and insisted he press ahead.46 His Royal Highness led his men forward a little way, but then halted again. This time General de Lacy Evans, whose 2nd Division was skirting round Bourliok, sent a rider begging Cambridge to advance, and he complied.

As the Highlanders marched ahead, ‘the vineyards and garden enclosures in the narrow valley through which the river runs, completely broke the formation of our troops’, complained Campbell.47 ‘It was impossible to keep our formation,’ confirmed Colour-Sergeant Cameron of the 79th, ‘stooping down and picking a bunch of luscious grapes, cramming them in your mouth regardless of stems and earth, for we were both dry and hungry, our three days’ rations having been exhausted that morning.’48 ‘I, for my part will always remember the round cannonballs, which came towards us with long hops and skips’, wrote Lord Wantage, ‘raising the dust and stones in showers wherever they touched but for the most part whizzing over our heads with a most disagreeable sound … A good many of our men never reached the Alma, but lay writhing amidst the vines and the brambles.’49

Fortunately, most of them did make it to the stream. ‘A thin hedge before us, we got through a slap two abreast and into the river which came up about my henches’, recalled Private Cameron. ‘Got some water to my mouth with my hand, the day being warm … After crossing we sheltered beside a little knoll until the rest had got through.’50

Momentarily cured of his indecision, the Duke of Cambridge urged Campbell to press on up towards the redoubts, but given the ragged efforts of the Light Division, Campbell was determined that his troops would join battle with parade ground perfection. Protected by the high south bank of the Alma, he ordered the ranks dress while the Black Watch’s pipers calmly played Blue Bonnets O’er the Border. Ahead, the ground rose up to a ridge before dipping slightly, approximately in line with the Great Redoubt, to climb again to the peak of Kourgane Hill. In the way lay two of Buller’s battalions: the 77th and the 88th. Campbell demanded that they join the advance. Buller had already ordered his brigade forward but the flat refusal of Colonel Egerton of the 77th sowed enough doubt in Buller’s mind to convince him to stay put. ‘You are madmen and will all be killed’, warned one soldier of the 77th, as Campbell’s brigade filed past.51

Meanwhile, up at the Great Redoubt, 3,000 men of the Vladimirsky Regiment were bearing down on Codrington’s left flank. Mistaken for the French, they advanced in safety right up to the Light Division before recognition dawned. Codrington had to abandon his hard-won position, picking his way through the bodies littering the slopes, back towards the Alma. The only British troops left near the Great Redoubt were Yea’s Royal Fusiliers.

The 1st Division was to advance as one, Bentinck’s Guards storming the Great Redoubt while Campbell’s Highlanders moved in on its flank, but Bentinck’s blood was up. ‘Forward, Fusiliers, what are you waiting for!’ he declared, and without waiting for the rest of the division, led the Scots Fusilier Guards up the hill.52 Only seven of the battalion’s eight companies were ready to move. Some hadn’t even had time to fix bayonets. ‘They got mixed with the beaten regiments of the Light Division, which retreated through them, and put them into confusion’, explained Sterling.53 By the time Sir Charles Hamilton, the Scots Fusiliers’ lieutenant-colonel, reached the redoubt, he had just five and a half companies left and found his battalion’s fire convincingly returned by the Russians. According to Kinglake, ‘with pistol in hand, for some of the Russian soldiery were coming close down, Drummond, the Adjutant of the battalion, rode up and gave the order to retire’.54 Sensing an opportunity, the Russians vaulted the walls of the redoubt and drove down upon the British in a bayonet charge.* The colour party made a gallant stand, resulting in VCs for three officers and one of the men, but the Russians had knocked the heart out of the Scots Fusiliers’ offensive, and gouged a glaring hole in the 1st Division’s line.

The duke now feared for the very survival of the Guards, and once again his courage deserted him. In that moment the fate of the battle, of the very campaign itself, hung in the balance. If the British retreated, the massed Russian battalions waiting up the hill would descend on them. One of the staff cried, ‘The brigade of Guards will be destroyed! Ought it not to fall back?’** ‘It is better, sir, that every man of Her Majesty’s Guards should lie dead upon the field than they should now turn their backs upon the enemy!’ thundered Sir Colin, puce-faced.***55 ‘The moment was an awful one’, Cambridge told his wife:

I had merely time to ask Sir Colin Campbell, a very fine old soldier, what was to be done. He said the only salvation is to go on ahead and he called to me ‘put yourself at the head of the Division and lead them right up to the Battery’.56

Having put some backbone into his superior, Campbell turned to outflanking the Russians and gaining the higher ground. In case they beat the Guards to the Great Redoubt, he offered a guinea to the first Highlander inside. His last battle on European soil had been at the passage of the Bidassoa in 1813, where the enemy had occupied a similarly entrenched, elevated position on heights across an estuary and where Colonel Greville had used an advance in echelon to great effect. Campbell now ordered his Highlanders forward in the same echelon formation, the 42nd on the right and a little ahead, the 79th on the left and a little behind, with the 93rd in the middle. Sterling was despatched to form the furthest battalion, the 79th, into column so that they might be more easily manoeuvrable in case of a Russian attempt on their flank.57 Campbell rode up front with the 42nd. Leading the Black Watch was Lieutenant-Colonel Duncan Cameron, only son of Campbell’s old 9th Foot commander Sir John Cameron, who had died in 1844.

‘Don’t be in a hurry about firing. Your officers will tell you when it is time to open fire’, Campbell had told the men. ‘Be steady. Keep silence. Fire low. Now men, the army will watch us. Make me proud of the Highland Brigade.’58 The Russians, having faced the disorganised Light Division, were unnerved to see this solid kilted line. ‘This was the most extraordinary thing to us, as we had never before seen troops fight in lines of two deep, nor did we think it possible for men to be found with sufficient firmness of morale to be able to attack in this apparently weak formation’, recalled one Polish officer.59 ‘I never saw troops march to battle with greater sang froid and order than those three Highland regiments’, remarked Campbell.60

The Russians’ diffidence persuaded Campbell to move the 79th from column back into line again. Reasoning that a gaggle of mounted officers would draw more fire than just one, he sent his staff officers back while he rode ahead in splendid isolation. At the crest of the first ridge he could make out two battalions of the Sousdal corps to his left. A further two lay out of sight to Campbell’s extreme right. Across the hollow in front of him and up the slope beyond were four Ouglitz battalions. None of these men had seen battle and all were fresh. On his left was Russian cavalry poised to ride him down. Dead ahead were two battalions of the Kazan regiment, and two of the Vladimir. The two Vladimir battalions had marched through the gap left by the retreating Scots Fusiliers, enduring fire on their left flank from the Grenadier Guards before turning to the right, past the rifles of the Coldstream Guards. Together with the Kazan troops to the right of the redoubt, they now pressed on towards the Highlanders. Altogether that meant twelve battalions facing Campbell’s three (see Plate 12).

Campbell was the only senior British commander on the field to have seen battle in the last decade. Chillianwala had shown him the obsolescence of the old Peninsular War tactic of holding fire until close to the enemy. He knew that with their new rifles, his Highlanders could decimate the Russians at a distance. By now the 42nd had caught up with their general and followed Campbell as he rode down into the hollow. ‘The men were too much blown to think of charging,’ he recalled, ‘so they opened fire while advancing in line, at which they had been practised, and drove back with cheers and a terrible loss both masses and the fugitives from the redoubt in confusion before them.’* But as the Black Watch marched forward, the Sousdal regiment on Campbell’s left descended into the hollow, threatening the 42nd’s flank. Campbell was about to order five companies to change front to repel them when ‘just at this moment the 93rd showed itself coming over the table of the heights’.61

‘Up the hill we went at the double’, wrote Private Cameron, ‘in a line two deep, in good order, but the hill getting steep, we stopped running and went on shoulder to shoulder keeping our places the best we could’.62 ‘The whistling of the balls was something wonderful,’ wrote Captain Ewart of the 93rd, ‘one broke the scabbard of my claymore; and MacGowan, who commanded the company of my right, got a ball through his kilt.’ As they reached the ridge Campbell noticed the 93rd’s disorder, and rode over. ‘“Halt, ninety-third! Halt!” he cried in his loudest tones, and we were all at once stopped in our career’, recalled Ewart. ‘It was perhaps as well that he did so, as the whole Russian cavalry were on the Russian right, and no great distance from us.’63 As musket balls whipped up the turf, Campbell insisted the men re-form properly. It was now that his best horse was killed under him. ‘He was first shot in the hip, the ball passing through the sabretache attached to my saddle, and the second ball went right through his body, passing through his heart’, recalled Campbell. ‘He sank at once, and Shadwell kindly lent me his horse, which I immediately mounted.’64

Once dressed to his satisfaction, Campbell gave the order for the 93rd to advance somewhat behind and to the left of the 42nd, to shoot into the flank of the Sousdal column, just as they had been planning to do to the 42nd. ‘For the first time we got a close look at the Russians, who were in column’, recalled one officer of the 93rd:

We at once opened fire, the men firing by files as they advanced. On getting nearer, the front company of the Russian regiment opposite to us, a very large one, brought down their bayonets, and I thought were about to charge us; but on our giving a cheer, they at once faced about and retired.65

Still the Russians had battalions to spare, and now it was the turn of the 93rd to be attacked. ‘Two bodies of fresh infantry, with some cavalry, came boldly forward against the left flank of the 93rd when … the 79th made its appearance over the hill, and went at these troops with cheers, causing them great loss, and sending them down the hillside in great confusion’,66 reported Campbell. ‘We were pressing the enemy hard and they were yielding inch by inch, although you could not see six yards in front of you, so dense was the smoke,’ recalled a sergeant of the 79th.67 And so, once again, the Russians were taken in the flank as they were attempting to take the British in theirs. The echelon formation had worked superbly. The ‘savages without trousers’, as General Karganoff called them, had trounced the enemy.68 Every column that had engaged Campbell was in retreat.

His position was still threatened by the Russian cavalry on his left and the four Ouglitz battalions to the south beyond the hollow. This block of infantry now began to bear down on the Highlanders but the Scotsmen’s solid fire sent them packing. ‘I never saw officers and men, one and all, exhibit greater steadiness and gallantry’, wrote Campbell in his despatch.69 ‘We reached the top, and the Russians not caring for cold steel, turned and fled’, wrote Private Cameron.70 The enemy only just managed to remove their guns from the Lesser Redoubt before it was overrun by two companies of the 79th under Major Clephane.

‘Our manoeuvre was perfectly decisive’, declared Sterling:

As we got on the flank of the Russians in the centre battery, into which we looked from the top of the hill, I saw the Guards rush in as the Russians abandoned it … If we had waited ten minutes, or even five minutes more, the Russians would have been on the crest of the hill first, and God knows what would have been the loss of the Highland Brigade.71

‘I feel I owe all to the excellent advice of Sir Colin Campbell who behaved admirably’, the Duke of Cambridge told his wife.72 Campbell was jealous of the laurels: ‘The Guards during these operations were away to my right, and quite removed from the scene of this fight … It was a fight of the Highland brigade.’73

The Ouglitz regiment tried to block the retreat of the other Russian battalions and force them to make a stand, but Lucan’s horse artillery discomfited them. ‘We got to the top just in time, and saw a column of infantry and artillery retiring up the ravine in front, about 1,100 yards off. We came into action at once, and plied them with shot and shell for a quarter of an hour and did great execution’, wrote one officer in the troop:

Captain Maude begged of Lord Lucan and Sir Colin Campbell to be allowed to advance down the hill, but Sir Colin said Lord Raglan’s positive orders were that no one should go beyond the ridge on which we then were … Neither Wellington nor Napoleon would have stopped short at this point.74

Meanwhile, in the middle of the allied line, de Lacy Evans’s 2nd Division had smashed through the enemy defences along the Sebastopol Road. To the west Canrobert’s guns, sent via Almatamack, crested the plain, let rip and forced the Russians back. Now, with artillery support at last, Canrobert’s infantry climbed the ravine and crossed the plateau towards Telegraph Hill. Aside from one sticky moment when the French mistook some discarded Russian knapsacks for soldiers and charged them, bringing a Russian barrage down on themselves,75 the advance was remorseless. The Zouaves soon had the tricolor planted on Telegraph Hill. Raglan was keen to press home the advantage with a general advance but Saint-Arnaud refused. After a long day in the saddle the French commander was feverish. His troops had left their packs at the river and, in his opinion, were unequipped to exploit the victory.

Raglan sent for Campbell. ‘When I approached him I observed his eyes to fill and his lips and countenance to quiver, but he could not speak’,76 wrote Campbell. ‘The men cheered very much. I told them I was going to ask the commander-in-chief a great favour – that he would permit me to have the honour of wearing the Highland bonnet during the rest of the campaign.’ Raglan agreed.

Back home, a public hungry for victory gorged on news of the Alma. It loosed a flood of rousing sheet music and bad poetry. Once again, William McGonagall singled Campbell out for praise:

Twas on the heights of Alma the battle began,

But the Russians turned and fled every man;

Because Sir Colin Campbell’s Highland Brigade put them to flight,

At the charge of the bayonet, which soon ended the fight.

Sir Colin Campbell he did loudly cry,

‘Let the Highlanders go forward, they will win or die,

We’ll hae none but Highland bonnets here,*

So, Forward, my lads, and give one ringing cheer.’

(continues for fifteen verses)

Campbell was the hero of the hour. In his account of the battle, Kinglake included a five-page panegyric about him. ‘Scotland, as she boasts no higher name, never yet produced a greater soldier, or a chieftain more beloved’, enthused another writer.77 His new image as a latter-day Robert the Bruce, tartan-clad, amid the skirl of the pipes, was one which Campbell seemed reluctant to contradict. The more the press found fault with the aristocratic generals, the more they held Campbell up as the honest soldier who had worked his way up by the sweat of his brow, despite the evidence to the contrary. ‘The battle [was] decided by the admirable movement of the Highland Brigade, under Sir Colin Campbell,’ reported the Morning Chronicle, ‘to whom everyone assigns the decisive movement which secured complete victory.’78 According to Russell of The Times, Campbell had told his men, ‘Don’t pull a trigger until you are within a yard of the Russians!’ ‘By not firing the bonnie Scots were enabled to advance with such rapidity that the enemy’s cannon had hardly time to get their range before they were out of it again. Consequently their loss was but slight compared with that of the other brigades.’79 Utter nonsense, of course. Not only did the Russians know the range very well, having staked the hillside, but Highland volleys fired at a distance beat back the enemy infantry before they had time to engage them closely. What saved the brigade from greater losses was their general’s shrewd use of terrain, and an appreciation that casualties suffered while a battalion formed were as nothing to those meted out when storming a hill harum-scarum. But does one really need much explanation as to why the most experienced brigade commander came away with some of the lightest casualties despite being in the thickest of the fray?

Six thousand Russians were killed or wounded. The French listed losses of 1,600 (later reduced to sixty killed and around 500 wounded). The bulk of allied casualties, around 2,000, were British, concentrated in the Scots Fusiliers and Grenadier Guards. ‘The first men who were brought in were struck by round shot, and had their legs torn off or shattered to pieces; they for the most part died’, recorded one doctor. ‘Then the terrible grape-shot wounds began to pour in, and in a short time we were surrounded with dozens of poor fellows, whose sufferings would shake the stoutest heart. One felt almost bewildered to know with whom to begin.’80 ‘We had a large number of regimental medical officers, but no regimental hospitals, and there were no field hospitals, with proper staff of attendants’, explained Surgeon Munro of the 93rd. ‘We had no ambulance with trained bearers to remove the wounded from the battlefield, and no supplies of nourishment for sick or wounded.’81

Very little of the blood was Scottish. The corrugated ground to the east had protected the Coldstream Guards and the Highlanders from the Russian guns. The 42nd lost five men killed and thirty-six wounded. The 79th had only two men killed and seven injured. The 93rd came in for the worst casualties of the brigade: Lieutenant Abercrombie was shot through the heart as he climbed the hill, a further four men lay dead and forty NCOs and men wounded. The most seriously injured were shipped to Scutari for treatment. ‘The sick and wounded, officers and men alike, were obliged to be packed more closely than negroes in a slaver, in the putrid holes of two or three transports’, wrote one soldier. ‘Many died on the way; others lived only until they reached the landing place.’82

There was, sadly, far worse in store. As at Walcheren, the Crimean campaign was premised on a coup de main and, as at Walcheren, unless executed speedily the army would wither without the enemy’s help. Murray’s Handbook to Russia warned that in the Crimea ‘the summer, in short, is one continued drought’, but that ‘the rains of autumn and the thaw in spring convert all the dust into such a depth of mud … that it is difficult to cross them without sinking up to the ankle’.83 A rapid advance was of the essence. Saint-Arnaud was keen to besiege Sebastopol but Raglan insisted on staying put to embark the wounded.84 For three days the allied army did not move.

Raglan and Saint-Arnaud planned to invest Sebastopol from the south, and so the allies set off in a wide circuit across the Tchernaya River to the port of Balaklava, to secure its harbour as a supply base. Unaware of Raglan’s southward push, Menschikoff meanwhile led his troops eastwards from Sebastopol into the Crimean countryside to wait on events. Almost the entire Russian army got across the allied line of march before Raglan and his staff rode right into the tail end of the enemy column. Neither side wanted to escalate the skirmish, so each kept to its own course.

As before, thirst, cholera and lack of carriage hampered their progress. Campbell’s men had to force their way through thick forest for four hours. ‘The heat was overpowering, not a breath of air percolated the dense vegetation’, recalled one soldier. ‘For a time, military order was an impossibility, brigades and regiments got intermixed. Guardsmen, Rifles and Highlanders straggled forward blindly, all in a ruck.’ That evening, Campbell’s brigade, ‘completely exhausted, parched with thirst, and their clothes much torn by struggling through the wood’,85 reached the Traktir Bridge and bivouacked near the village of Tchorgoun. The next morning, after a three-hour march across a broad plain carpeted in wild thyme, they found the little village of Kadikoi, just north of Balaklava, abandoned. In half an hour it was stripped and gutted. ‘The men seemed to do it out of fun’, wrote Sterling. ‘They broke boxes and drawers that were open, and threw the fragments into the street.’86

To test Balaklava’s defences, Raglan sent the Rifles and horse artillery south through the gorge leading to the town. The Russian commandant, Colonel Monto, fired a few shells from the old Genoese castle near the harbour mouth, but the only damage caused was a tear to the coat of Raglan’s assistant military secretary. HMS Agamemnon sailed into the port to secure the wharfs. The residents seemed relieved to surrender.

Raglan set up his headquarters in the commandant’s house. On 27 September, the 3rd and 4th Divisions tramped up to the Sapoune Heights, south of Sebastopol, while Campbell’s Highlanders, still waiting for their tents, bivouacked on the plain north of Balaklava with the rest of the army. It was harvest time and the countryside was fruitful. ‘At the present moment we are in clover,’ wrote a surgeon of the Scots Fusilier Guards, ‘surrounded by delicious grapes, peaches and apples, with plenty of Crimean sheep and cattle.’87 Campbell was unmoved. ‘I have neither stool to sit on, nor bed to lie on, I have not had off my clothes since we landed on the 14th’, he complained to a friend on 28 September. ‘Cholera is rife among us, and carrying off many fine fellows of all ranks.’88

Having seen Sebastopol’s defences for himself, Raglan was now convinced of the need for a heavy artillery barrage prior to any infantry assault. Architect of the Russian entrenchments was Lieutenant-Colonel Franz Ivanovitch Todleben. In one month he had raised a formidable chain of earthworks strengthened with six great bastions. ‘We are in for a siege, my dear sir,’ Campbell warned Russell of The Times, ‘and I wonder if you gentlemen of the press who sent us here took in what the siege of such a place as Sebastopol means.’89 In fact, the enemy was very far from besieged. ‘The Russians have got free ingress and egress north and east, as our army is not large enough to surround the whole place’, pointed out Sterling.90

On 2 October the 93rd were selected to remain near Balaklava to unload munitions and guard the harbour; a chore they saw as robbing them of the chance to storm Sebastopol. The 42nd and 79th, plus the Guards, marched up to the plateau and encamped about a mile behind the 2nd Division, near a windmill. Campbell’s brigade was finally issued with the tents they had been missing since leaving Calamita Bay. On the 5th, Raglan moved his headquarters to the Sapoune Heights, about halfway between Balaklava and Sebastopol. The crack shots from the 79th were sent forward to keep the Russians pinned down while the artillerymen built batteries. Seven days later, suspicious that closet Russophiles were about to set fire to the port, Raglan ordered all adult male inhabitants to be expelled from Balaklava. Two hundred soldiers of the 93rd, under Major Leith Hay, rounded them up. ‘When we went to their houses and ordered them away,’ wrote Private Cameron, ‘the shrieking of the women and crying of children was more trying, I thought, than a column of Russians.’91

On the 14th, Raglan placed Campbell in charge of all British and Turkish troops ‘in front of and around Balaklava’. Aside from the 93rd, the principal allied force defending the port was Lucan’s cavalry camped in the valley to the north. Campbell assumed that he, a brigade commander, would serve under Lucan, a divisional commander, but Raglan explained that Campbell’s was to be an independent command. ‘Lord Raglan would not trust Lord Lucan to defend Balaklava,’ scoffed Captain Maude of the Royal Horse Artillery, ‘so sent down Sir Colin Campbell.’92 ‘This is calculated to inspire confidence, even more than the seasonable arrival of 3,000 Turks’, wrote visiting politician, Sir Edward Colebrooke.93 ‘As soon as the Chief made it known that the place was in charge of Sir Colin, people went to an extreme of confidence, and ceased to imagine that ground where he was commanding could now be the seat of danger’, confirmed Kinglake.94

At last, on 17 October, Raglan felt he had enough artillery in place to unleash a decisive bombardment of Sebastopol, but when, after a day’s pounding, the guns ceased fire, General Canrobert* and his men had been alarmed by the explosion of a French magazine and were reluctant to pile in. The offensive was postponed. The barrage continued every day for a week, but each night Todleben’s men would venture out to repair the defences.

While the campaign outside Sebastopol ran into the sand, rumours grew of a huge Russian army massing to the east, ready to storm Balaklava. On the 18th, and again on the night of 20/21 October, massive enemy columns approached the port, in what looked like a reconnaissance in force. On the first occasion Raglan sent the rest of the Highland Brigade down as a precaution. On the 20th, following a request for reinforcements from Campbell, Brigadier-General Goldie arrived late with 1,000 men, delayed because of fog. Campbell informed him gruffly that ‘it was no use sending troops to him unless they were sent in the evening, saying that when it was daylight he could do very well, and did not want any help’.95

Then, four days later, allied fears were confirmed. Campbell and Lucan discovered from a Turkish spy ‘that 20,000 infantry and 5,000 cavalry were marching against our position at Balaklava, from the east and south-east’. ‘We considered his news so important that Sir Colin Campbell at once wrote a report to Lord Raglan,’ recalled Lucan, ‘and I had it conveyed to his Lordship by my aide-de-camp, who happened on that day to be my son’.96 Lucan’s heir, Lord Bingham, rode from Kadikoi to Raglan’s headquarters, and handed the message to Airey. He made no comment and passed it to Raglan. Raglan disapproved of using spies. It was ungentlemanly. He pondered the matter for a while, composed a reply and handed it to Lord Bingham, who pocketed it and rode back with all speed to Balaklava.

Some while later a breathless Lord Bingham reached Campbell’s headquarters, dashed in and handed him Raglan’s reply. It was just two words in acknowledgment: ‘Very Well’.

* William Russell of The Times is often credited as the first war correspondent, and the Crimea the first war to be so reported, but one of Campbell’s earliest battles, Corunna, was covered in 1809 by Henry Crabb Robinson of The Times. Russell has a claim, as one of his biographers put it, to be the first ‘professional’ war correspondent, but the Crimea was not even his first war (Furneaux, 16–17).

* Generals with no experience of battle included Scarlett, Bentinck, Codrington, the Duke of Cambridge and Lord Cardigan. The experience of the rest since 1815 was extremely limited.

** See note on p. 15.

* Raglan, Cardigan and Lucan were all peers. Cathcart was the son of an earl, Strangways the nephew of the second Earl of Ilchester and Sir Richard England’s mother was from a cadet branch of the family of the Marquess of Thomond. Scarlett was the son of Lord Abinger. Adams came from Warwickshire gentry and Tylden’s family had held estates in Kent since the reign of Edward III. Bentinck was the grandson of the Earl of Athlone. Sir John Campbell was the son of Lieutenant-General Sir Archibald Campbell, baronet. Buller’s father had been a full general. Torrens was the son of Major-General Sir Henry Torrens. Codrington was the son of an admiral. Eyre was the son of a vice-admiral and his maternal grandfather had been a baronet. The only general with a chequered ancestry (apart from Campbell) was Sir John Burgoyne, the illegitimate son of the famous Lieutenant-General Burgoyne and singer Susan Caulfield, but then he was there only as an adviser.

** Despite a German doctor condemning it as pestilential (Quarterly Review, December 1854, 203).

*** A flannel cummerbund supposed to prevent a chilled abdomen, regarded as a cause of the disease. See the War Office’s Instructions to Army Medical Officers for their Guidance on the Appearance of the Spasmodic Cholera in this Country (1848).

* As one colonel wrote, it would have been easier to take the knapsacks to carry all this, and keep it dry (Ross-of-Bladensburg, 66–7).

** Their elaborate uniforms suggested the cavalry were poseurs rather than soldiers, especially the 11th Hussars. ‘The brevity of their jackets, the irrationality of their head gear, the incredible tightness of their cherry-coloured pants, altogether defy description’, wrote one reader of The Times, who had evidently examined their uniforms in detail. ‘But sir, for war service it is as utterly unfit as would be the garb of the female hussars in the ballet of Gustavus, which it very nearly resembles.’ He demanded that the commander-in-chief ‘be prevailed upon to allow the unhappy 11th to have the tightness of their nether integuments relaxed and their bottoms releathered’ (The Times, 22 April 1854).

* French light infantry, originally recruited in French North Africa, who wore an exotic uniform of harem trousers, open fronted jacket and a turban or floppy fez. ‘Infinitely superior in physique and spirit to the ordinary French conscript’ (Wolseley, Story of a Soldier’s Life, I, 139–40).

* Lysons (104), Evelyn (119) and Wantage (30) all suggest that the Scots Fusiliers retreated. Thirty-four years later, Wantage changed his mind. ‘Not one yard of the ground that a man had gained did we ever give up during that advance’, he wrote. In the same account, Wantage claims the Highland Brigade had ‘no Russian force in front of it’, so it seems his recollection had become warped (Wantage, 36).

** Kinglake claims that no one knew who the officer was. He may have been saving the Duke of Cambridge’s blushes. According to another officer, ‘The Duke of Cambridge ordered his division to retire but old Sir Colin Campbell said, “The Highlanders never retire with an enemy in front, your Royal Highness”’ (Essex Standard, 8 November 1854). Another version was ‘No Sir, British troops never do that, nor ever shall while I can prevent it’ (St Aubyn, 70).

*** ‘The warmth of my speech was occasioned by the urgency of the moment’, Campbell later told the duke (RA/VIC/ADDE/1/3937).

* The 42nd had been drilled to fire while advancing by Colonel Cameron, who had learnt it from his father.

* This phrase was widely attributed to Campbell, but when Russell asked him four years later if it was true, ‘His lordship said it was a complete fiction’ (Russell, My Indian Mutiny Diary, 225).

* Saint-Arnaud had died of cholera on 26 September, relinquishing command to General Canrobert.

1 Figes, 195.

2 Fortescue, XIII, 33.

3 Woodward, 268.

4 Wolseley, Story of a Soldier’s Life, I, 98.

5 Eckstaedt, I, 85.

6 Woodham-Smith, 258.

7 Barnett, 286.

8 Shadwell, I, 316.

9 RNRM/44.2.

10 Sterling, Story of the Highland Brigade, xviii, 226, 247.

11 The Carlyle Letters Online, Letter from Thomas Carlyle, 6 March 1854 (carlyleletters.dukejournals.org).

12 Shadwell, I, 68.

13 Anon., The History of the Times, I, 420.

14 RNRM/44.2.2.

15 Cavendish, 87; Linklater, 95; Richards, II, 37.

16 Prebble, 317, 321.

17 Shadwell, I, 317.

18 ‘Officers serving on the Staff in the capacity of Brigadiers-General are to take rank and Precedence from their Commissions as colonels in the Army, not from the date of their appointments as Brigadiers’ (Queen’s Regulations [1844], 3).

19 Sterling, Story of the Highland Brigade, 135.

20 Dallas, 83.

21 Currie, 30–1.

22 Wolseley, Story of a Soldier’s Life, I, 80.

23 Woods, I, 149.

24 St Aubyn, 68.

25 Ross-of-Bladensburg, 45.

26 Reilly, 1.

27 Sterling, Story of the Highland Brigade, 61.

28 Wrottesley, II, 83.

29 Wantage, 25.

30 Munro, 11.

31 Cameron, 74.

32 Sterling, Story of the Highland Brigade, 65.

33 Woods, I, 319.

34 USM, February 1855,194.

35 Sterling, Story of the Highland Brigade, 136.

36 Mitra, 320; USM, February 1855, 194.

37 Chadwick, 22.

38 Fortescue, XIII, 51, 73.

39 Kinglake, III, 90.

40 Heath, 60.

41 Shadwell, I, 322; Colebrooke, 37.

42 Gibbs, 73.

43 Bairstow, 28.

44 Sterling, Story of the Highland Brigade, 70.

45 Marsh, 129.

46 Kinglake, III, 135.

47 Shadwell, I, 323.

48 Murray, D., II, 49.

49 Wantage, 34.

50 Cameron, 74.

51 Sterling, Story of the Highland Brigade, 70.

52 Maurice, II, 81; Fortescue, XIII, 66; Ross-of-Bladensburg, 80–1.

53 Sterling, Story of the Highland Brigade, 75.

54 Kinglake, III, 218.

55 Kinglake, III, 232–3.

56 St Aubyn, 72; Vincent, 197.

57 Kinglake, III, 233.

58 Kinglake, III, 257.

59 Hodasevich, 70.

60 Shadwell, I, 325.

61 Shadwell, I, 324.

62 Cameron, 74.

63 Ewart, I, 230–1.

64 Shadwell, I, 321.

65 Burgoyne, 106.

66 Shadwell, I, 324.

67 Murray, D., II, 50.

68 Calthorpe, 42; Wright, H.P., 50.

69 Sterling, Story of the Highland Brigade, 68.

70 Cameron, 75.

71 Sterling, Story of the Highland Brigade, 71, 75.

72 St Aubyn, 72.

73 Shadwell, I, 325.

74 Marsh, 131.

75 Hodasevich, 71–2.

76 NAM/1967-06-7.

77 Anon., The Battle of Alma, 50.

78 Morning Chronicle, 14 October 1854.

79 The Examiner, 21 October 1854.

80 USM, February 1855, 196.

81 Munro, 11.

82 USM, November 1854, 433.

83 Jesse, 153–4.

84 Calthorpe, 41.

85 Ross-of-Bladensburg, 100–1.

86 Sterling, Story of the Highland Brigade, 75.

87 Bostock, 203.

88 Shadwell, I, 325.

89 Russell, The Great War with Russia, 108–9.

90 Sterling, Story of the Highland Brigade, 76.

91 Cameron, 78.

92 Woodham-Smith, 207.

93 Colebrooke, 44.

94 Kinglake, IV, 234–5.

95 Ewart, I, 262.

96 Lucan, 6.