‘I’ll tell you something else, which military historians never realise: they call the Crimea a disaster, which it was, and a hideous botch-up by our staff and supply, which is also true, but what they don’t know is that even with all these things in the balance against you, the difference between hellish catastrophe and a brilliant success is sometimes no greater than the width of a sabre blade, but when all is over no one thinks about that. Win gloriously – and the clever dicks forget all about the rickety ambulances that never came, and the rations that were rotten, and the boots that didn’t fit, and the generals who’d have been better employed hawking bedpans round the doors. Lose – and these are the only things they talk about’

George Macdonald Fraser, Flashman at the Charge

‘We have an unfortunate mania for going right into the cannon’s mouth, instead of taking the side road’

Henry Layard

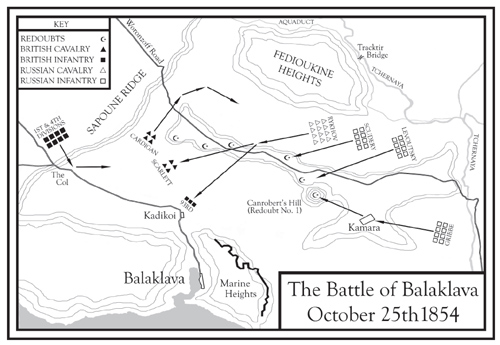

The port of Balaklava nestled behind a cordon of hills. To the west these hills merged into the plateau south of Sebastopol, while eastwards they shouldered their way along the Crimean coast. A track from the harbour led north past Kadikoi until, about 2 miles north, it joined the Woronzoff Road, a metalled highway which led north-west to Sebastopol, and in the other direction curved round and headed due east along a natural viaduct of high ground called the Causeway Heights. Beyond the Causeway Heights was the North Valley, bounded to the north by the Fedioukine Hills, and to the east by Mount Hasfort and an embanked aqueduct. From here the ground sloped down to the Tchernaya River. Below the Causeway Heights lay the South Valley, hemmed in to the east by the Kamara Hills, and to the west ending in a narrow ravine, the ‘Col’, which led to the Sapoune Ridge.

To guard the Woronzoff Road, Raglan had ordered the construction of six separate redoubts, each big enough to house 250–300 troops. They were widely spaced, some over a mile apart, and all of them more than a mile from Campbell’s headquarters at Kadikoi. The Turks had provided eight battalions (4,700 men) for their defence, commanded by Rustem Pasha and answerable to Campbell. Work on the redoubts had started on 7 October, but eighteen days later they were still half-finished. Redoubt No. 2 had benefited from just one day’s labour. ‘These works are not strong’, warned one officer. ‘I am sorry to say these Turks don’t seem worth very much; they are very idle, and there is the greatest difficulty in getting them to work, even though it is for their own security and comfort.’1 The most easterly, Redoubt No. 1, on what had been christened ‘Canrobert’s Hill’, was the strongest, but it remained vulnerable to artillery, overlooked as it was by the Kamara Hills to the south-east. Cavalry could jump both its ditch and walls. Nevertheless, Raglan was reluctant to denude the batteries bombarding Sebastopol, so Campbell received only nine light guns for all six redoubts.* Three were in Redoubt No. 1 and two each in the next three redoubts, leaving none at all in Redoubts 5 and 6.2

Most of the rest of Campbell’s artillery was positioned on the far side of the South Valley, guarding the approaches to Balaklava. On a rise slightly north of Kadikoi the 93rd had a battery of seven guns (Battery No. 4), and behind the village were a further five guns, manned by crewmen from HMS Niger and Vesuvius. In the hills to the east of the port lay more Royal Artillery and Royal Marine Artillery batteries, armed with some impressive 32-pounder howitzers.3 As for infantry, Campbell had the 93rd camped in front of Kadikoi and some mixed Turkish infantry plus Royal Marines to the north and east of the village. A further 1,200 Royal Marines under Colonel Hurdle guarded the heights east of Balaklava. Down in the harbour were HMS Wasp and Diamond, but the former had only one gunner and a skeleton crew, and the latter just a shipkeeper. On 26 September, Raglan had ordered ‘the least efficient soldiers of each regiment’4 to form an invalid battalion at Balaklava, but so far it numbered just a few dozen men. Meanwhile, the bulk of the army was camped 7 miles away, in front of Sebastopol. Back in Varna, the Guards had struggled to march 5 miles in a day. They had got no fitter, so if Campbell needed the rest of the 1st Division, it would not arrive for several hours.

Nevertheless, Campbell was uncharacteristically blasé. ‘I think we can hold our own against anything that may come against us in daylight’, he reported. ‘I am however, a little apprehensive about the redoubts if seriously attacked during the night.’ ‘I cannot say whether Sir Colin Campbell’s sense of security was in any degrees found upon the cavalry, or whether, for once, he went along with the herd in his estimate of what could be insured by a little upturn of soil with a few Turks standing behind it’, wrote Kinglake,5 but whatever its basis, such confidence from a general known for his caution was doubly reassuring.

Balaklava Harbour. Photograph by R. Fenton. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

The cavalry Kinglake mentioned consisted of Lucan’s 1,500 sabres, deployed north-west of Kadikoi. Campbell had great confidence in Lucan, and the earl, in turn, frequently deferred to his more experienced, but junior, major-general. He wrote of Campbell, ‘a more gallant or useful soldier there is not in the army’,6 and his respect was reciprocated.** ‘Whilst others have been croaking, grumbling and dissatisfied, you have always laughed at every difficulty’, Campbell told Lucan.7 That said, Campbell’s regard for Lucan’s officers was more grudging. Having ‘been a good deal taunted with not having yet done anything’,8 their eagerness grated. Campbell complained to Lord George Paget*** that cavalry officers:

would fall out from their regiment and come to the front and give their opinion on matters they knew nothing about, instead of tending to their squadrons, as I would make them do. Why, my lord, one with a beard and moustaches, who ought to have known better, said to me to-day, ‘I should like to have a brush at them down there’, when I replied, ‘Are you aware, sir, that there is a river between us and them?’ These young gentlemen talk a great deal of nonsense … I am not here to fight a battle or gain a victory; my orders are to defend Balaklava, which is the key to our operations, my lord, and I am not going to be tempted out of it.9

Temptation, in the form of General Liprandi’s Russian army, had moved off at 5 a.m. on the 25th: 24,000 men and seventy-eight guns in three massive columns.10 By 6 a.m. the mist which had hidden their advance had lifted enough for Liprandi’s artillery to take aim. Lucan was out early with his staff. ‘We rode on at a walk across the plain, in the direction of the left of “Canrobert’s Hill” in happy ignorance of the day’s work in store for us’, recalled Paget:

By the time we had approached to within about three hundred yards of the Turkish redoubts in our front, the first faint streaks of daylight, showed us that from the flag-staff, which had, I believe, only the day before been erected on the redoubt, flew two flags, only just discernible in the grey twilight.

‘What does that mean?’ asked Lord William Paulet, Lucan’s assistant adjutant-general. ‘Why, that surely is the signal that the enemy is approaching’, replied Major McMahon. ‘Hardly were the words out of McMahon’s mouth when bang went a cannon from the redoubt in question.’11

At Kadikoi, Surgeon Munro of the 93rd was ‘startled by the boom of a gun away in the distance on our right, followed almost immediately by the nearer report of answering guns, and by wreaths of white smoke curling upwards from our No. 1 Redoubt’.12 Immediately, Campbell ordered out every soldier under his command. ‘The batteries were all manned, and the Royal Marines lined the parapets on the eastern heights of the town’, recalled Raglan’s nephew.13 Campbell then rode across the valley to confer with Lucan and get a closer look at the enemy. As the sun rose, dust clouds marking the Russian advance were visible. A column under General Gribbe had already swept up the Baidar Valley and taken the village of Kamara. From here he could pound Redoubt No. 1, assisted by ten guns under General Semiakin, who occupied the higher ground to the north. Heading for Redoubt No.2 were three more battalions and ten guns under General Levoutsky, while Colonel Scudery bore down on No. 3 with four battalions, a company of riflemen, three squadrons of Cossacks and a field battery.

The Turks at Redoubt No. 1 opened fire before the Russians could unlimber their guns, taking the head off one of the enemy drivers, but the Russians returned fire, hitting a powder magazine. At the same time, the Marine artillery east of Balaklava tried desperately to target the enemy, but the range was too great. Campbell despatched his one field battery under Captain Barker to Redoubt No. 3, but Barker found he could not hit the Russians assaulting Canrobert’s Hill, so instead aimed at those occupying the Fedioukine Heights. Lucan ordered Captain Maude’s 6-pounder battery to set up between Redoubts nos 2 and 3, but his guns were light, his ammunition scanty, and Maude himself was soon blown into the air by a Russian shell. Barker sent more guns under Lieutenant Dickson in support while Lucan led his Heavy Brigade in ‘demonstrations’ towards the Russians. His manoeuvres left the enemy unfazed.

It took the Russians an hour and a half to subdue Redoubt No. 1, by which time 170 Turks lay dead. Rustem Pasha’s men, mainly raw recruits from Tunisia, had been without food (or more accurately, food acceptable to Muslims) for days.14 Having seen their first redoubt fall, ‘some kind of panic and fear overcame the Turks,’ reported General Ryzhov, ‘so that they were unable to withstand the approach of our infantry’.15 ‘Directly the Turks found they were being fired into, they dispersed like a flock of sheep,’ wrote Lieutenant-Colonel Calthorpe, ‘numbers throwing away their arms and accoutrements to facilitate their flight.’*16 As they fled, Russian cavalry and artillery pursued them without mercy. Finding themselves under fire, Lucan’s cavalry now pulled back westwards beyond Redoubt No. 4. ‘Our gradual retreat across that plain, “by alternate regiments”, was one of the most painful ordeals it is possible to conceive,’ wrote Paget, ‘seeing all the defences in our front successively abandoned as they were, and straining our eyes in vain all round the hills in our rear for indications of support.’17

It was now around 7.30 a.m. ‘Never did the painter’s eye rest on a more beautiful scene than I beheld from that ridge’, reported William Russell of The Times, from his position next to Raglan on the Sapoune Ridge. ‘The fleecy vapours still hung around the mountain tops, and mingled with the ascending volumes of smoke; the patch of sea sparkled freshly in the rays of the morning sun, but its light was eclipsed by the flashes which gleamed from the masses of armed men below.’18 Even from this distance General Canrobert could make out Campbell, Shadwell and Lieutenant-Colonel Ainslie of the 93rd outside Kadikoi. Canrobert had already ordered infantry brigades under Vinoy and Espinasse, plus eight squadrons of Chasseurs d’Afrique,** down to the valley below. Raglan had instructed the rest of Cambridge’s 1st Division to march for Balaklava, ordering the duke to put himself under Campbell’s orders. Sir George Cathcart’s 4th Division would follow in support. Meanwhile, worried that the attack might be a huge feint, Raglan warned Sir Richard England to be on his guard for a Russian sortie from Sebastopol. ‘Lord Raglan was by no means at ease’, wrote Russell.’There was no trace of the divine calm attributed to him by his admirers as his characteristic in moments of trial … Perhaps he alone, of all the group on the spot, fully understood the gravity of the situation.’19

Cambridge’s men set off at double quick time at 8 a.m. Cathcart, however, having read his orders, assured Raglan’s ADC (Captain Ewart of the 93rd) that it was quite impossible. Brigadier-General Goldie had been on a wild goose chase to Balaklava five days ago, and received no thanks from Campbell for his efforts, so Cathcart advised Ewart to sit down and have some breakfast instead. Ewart replied that he would not leave until the 4th Division was ready to move. Cathcart offered to confer with his staff and after a while Ewart heard the bugles sounding the order to turn out.

Until these reinforcements arrived, the only force in the valley available to Campbell was Lucan’s cavalry. Granted permission to live aboard his steam yacht Dryad in Balaklava harbour, Lord Cardigan had yet to emerge, so Lucan took direct command of the Light Brigade. Campbell and Lucan had agreed that if the redoubts fell, the cavalry would take up position to the north-west of Kadikoi, so that, should the Russians cross the South Valley, Lucan could bear down on their flank, while still leaving the 93rd a clear shot at the enemy. Raglan had other ideas and ordered eight squadrons of heavy cavalry to support the 93rd, while the rest of the cavalry redeployed beyond Redoubt No. 6.

While these dispositions proceeded, Campbell formed up the 93rd a little way down the north slope of the hill north of Kadikoi, with their left slightly forward and the light company in front. As the routed Turks piled past towards Balaklava, Lieutenant Sinclair of the 93rd, claymore in hand, tried unsuccessfully to stop them. Behind the rise was Mrs Smith, spouse of Sinclair’s batman, ‘a stalwart wife, large and massive, with brawny arms, and hands as hard as horn’, according to the regimental surgeon, but within whose ‘capacious bosom beat a tender, honest heart’. She had been laying laundry out to dry next to the small stream which snaked behind the hill. Flushed with rage at the sight of Turks trampling her washing, and spitting profanities, she laid into them with a stick, and, grasping one by the collar, dealt him a well-aimed kick.20 The Balaklava harbour master, Captain Tatham, benefiting from a light grasp of Turkish, managed to re-form some, but most bolted. One eyewitness saw them pour into the port, ‘laden with pots, kettles, arms and plunder of every description, chiefly old bottles, for which the Turks appear to have a great appreciation’.21

Back on the rise, the Highlanders now felt the force of the Russian guns unlimbered between Redoubts Nos. 2 and 3. ‘Round shot and shell began to cause some casualties among the 93rd Highlanders and the Turkish battalions on their right and left flanks’, reported Campbell, so ‘I made them retire a few paces behind the crest of the hill’.22 The barrage had cost Private McKay his leg, while Private Mackenzie suffered a shell splinter to his thigh. At the same time, ‘Tens of thousands of cavalry and infantry could be plainly seen pouring down from Kamara, up from the river and valley of the Tchernaya, and out of the recesses of the hills near Tchorgoun to challenge our grip on the Chersonese’,* reported Russell. ‘The morning light shone on acres of bayonets, forests of sword blades and lance-points, gloomy-looking blocks of man and horse.’23 Their first goal was to obliterate Campbell’s little force. General Scarlett’s orderly in the Heavy Brigade saw the Russian cavalry bearing down on them: ‘As they passed in front of us a few hundred yards the thought was in my mind, oh, the poor 93rd, they will all be cut up. There is more than fifty to one against them.’24

The 93rd at Kadikoi were under strength, two companies under Major Gordon having been despatched to the heights east of Balaklava to help the Marines with their entrenchments, so Campbell had sent Sterling to Balaklava to raise the alarm; Lieutenant-Colonel Daveney scrabbled together 100 invalids while two Guards officers, Verschoyle and Hamilton, appeared unprompted with another thirty to forty men. Lastly a Polish interpreter with the Royal Artillery secretly crept up and joined the rear rank of the 93rd, armed with an elderly shotgun. By now 400 Russian cavalrymen had broken away from the main corps under General Ryzhov, and were thundering towards the 93rd. Barker’s battery, on the left of the Highlanders, together with the guns on the Marine Heights, started plugging away as they came within range. Normal practice for infantry facing cavalry was to form square, as Colonel Browne had done forty-three years ago at Barrosa Hill, but it reduced potential firepower in front by three-quarters. Instead, Campbell ordered the men into line, two deep, ready to advance over the crest of the rise to meet the enemy. He was placing great trust in their mettle: the 93rd’s record for steadfastness was patchy. In 1831, at Merthyr, their bayonets had been batted aside by Welshmen armed only with staves.25

Campbell had seen the power of the Minié rifle at the Alma, and though tutored in the close action, cold steel school of warfare, he had grasped the new weapon’s potential to kill at long range. Even so, if the line broke or the Russians skirted round the end, the Highlanders would be slashed to pieces. It was a supreme gamble, an all-or-nothing tactic. Campbell knew it, and rode down the line shouting, ‘Remember, there is no retreat from here, men! You must die where you stand!’ ‘Ay, ay, Sir Colin, and needs be we’ll do that!’ replied Private John Scott in No. 6 company, his cry soon echoed by the rest.26

Just as the Scotsmen prepared to face their enemy, Major Gordon’s two missing companies appeared. When Gordon had seen the Turks abandoning the redoubts, he had marched his men as fast as possible the 2 miles to Kadikoi. Sadly his arrival was more than offset by the flight of the Turks on each flank, scared away by the rumble of the accelerating Russian cavalry, thus robbing Campbell of two-thirds of his men.** ‘The advancing Russians, seeing this cowardly behaviour on the part of our allies, gained fresh courage themselves’, explained Raglan’s nephew, ‘and came on with a rush, yelling in a very barbarous manner.’27 At the Light Brigade camp, one of the officer’s wives watched in dread as the enemy swept across the valley towards the 93rd: ‘Ah, what a moment! Charging and surging onward, what could that little wall of men do against such numbers and such speed?’28 ‘With breathless suspense’, wrote Russell, ‘every one awaits the bursting of the wave upon the line of Gaelic rock.’29

Campbell launched the first volley at the very limit of the Minié’s range. The order ‘Fire!’ echoed across the valley, immediately muffled by the crack of 600 rifles. ‘Being in the front rank, and giving a look along the line, it seemed a wall of fire in front of the muzzles’, wrote one private. In his excitement Campbell had ridden in front of the Highlanders, and had to wheel rapidly out of the way. Yet through the gunsmoke, he saw scarcely a single Russian unseated. The Highlanders fired a second volley, but it too seemed to have little effect on the wall of riders nearing the hill. Now the first Russian squadron started to swerve off to its left, to exploit the thin British line at its end, from where the Turks had fled. ‘Shadwell, that man understands his business’, said Campbell to his ADC.30

‘93rd! Damn all that eagerness!’ Campbell bellowed as some of the men in their enthusiasm brought their rifles up to the charge. To meet the new threat, he ordered the grenadier company under Captain Ross to wheel to the right and form a line at right angles. As the Russians closed in for the kill, they found themselves enfiladed at close range.*** ‘It shook them visibly’, wrote Surgeon Munro, ‘and caused them to bend away to their own right until they had completely wheeled, when they rode back to their own army, followed by a burst of wild cheering from the ranks of the 93rd.’31

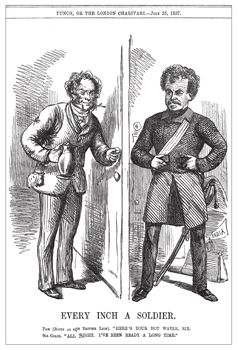

‘Had the 93rd been broken,’ claimed Sterling, ‘there was literally nothing to hinder the cavalry which came down on the 93rd from galloping through the flying Turks, and destroying all the stores in Balaklava.’32 Aside from the two men wounded early on by enemy artillery, there had been no other casualties among the 93rd. From Russell’s viewpoint, the Russian charge seemed to have been repelled by little more than a ‘thin red streak topped with a line of steel’, or as in Kipling’s abbreviated version, a ‘Thin Red Line’* (see Plate 14).

But amid all the backslapping and hurray-ing, one uncomfortable fact intruded: the Russians now knew just how few men guarded the gorge to Balaklava. The 93rd had withstood 400 Russian cavalrymen, but the enemy could send five times that number next time.

![]()

Raglan, convinced that the enemy’s goal was Balaklava itself, warned Captain Tatham, ‘The Russians will be down upon us in half an hour; we will have to defend the head of the harbour; get steam up.’33 Cathcart’s division, still marching down the Col, received new orders to turn northwards and retake the Causeway Heights. On seeing the redoubts a shocked Cathcart exclaimed, ‘It is the most extraordinary thing I ever saw, for the position is more extensive than that occupied by the Duke of Wellington’s army at Waterloo.’34

Meanwhile, the rest of the Russian cavalry had been proceeding along the North Valley. Under fire from British guns on the Sapoune Ridge, they rode over the Causeway Heights and into the South Valley, but found themselves facing General Scarlett’s little brigade of heavy cavalry. From where Lord Euston stood, up on the ridge, the Russian cavalry next to the Heavy Brigade looked like ‘a large sheet to a small pocket handkerchief’.35 Heavy cavalry relied on shock tactics, on weight and momentum to blast through the enemy, but the Russian squadrons up the slope in front of Scarlett formed one huge, unwavering mass. In any case, charging uphill at superior enemy cavalry was most unwise, but this was Scarlett’s first battle, and unencumbered by cavalry precedent he ordered his men into formation.

Like Campbell at the Alma, Scarlett was determined to advance ceremoniously. The British had not finished dressing their ranks before the Russians began to descend, ‘advancing at a rapid pace over ground most favourable, and appearing as if they must annihilate and swallow up all before them’.36 As the enemy drew near, the British troopers continued their dispositions until they met with their commander’s approval, and then the portly, short-sighted Scarlett, furiously brandishing his sword, began his first and last charge (see Plate 15).

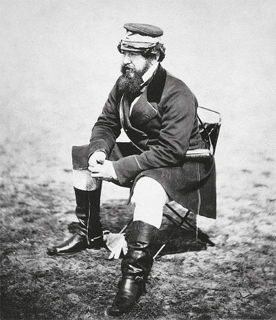

William Russell. Photograph by R. Fenton. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

The Russians were formed rather in the manner of the Zulu ‘horns of the buffalo’, with a broad rank in front spreading out in two wings to the sides, and cavalry in column behind the middle. They graciously halted, watching incredulously as the little band of gilded troopers in front of them gathered speed. ‘We followed with our eyes and our hearts as the Greys began to advance slowly, then to quicken their pace, until at a gallop the whole line rolled along like a great crested wave, and dashed against the solid mass of the enemy, disappearing from our sight entirely’, reported Surgeon Munro, watching from across the valley.37 First in were the Scots Greys beside the Inniskilling Dragoons, hacking at anything that moved, swiftly followed by the Royals and the 4th and 5th Dragoon Guards. Finding their sabres were bouncing off the thick Russian overcoats, they resorted to punching their enemy with their sword hilts. Scarlett received five wounds, but kept gamely slogging away. ‘We soon became a struggling mass of half-frenzied and desperate men,’ wrote Sergeant Major Franks of the 5th Dragoon Guards, ‘doing our level best to kill each other.’38

From Kadikoi, Campbell had watched with respect and disbelief as Scarlett ordered his brigade to charge. He had sent forward two of Barker’s guns, assisted by the Marine artillery, to rain down round shot over Scarlett’s head and into the centre and rear of the enemy cavalry. Campbell saw the light mounts of the 2nd Dragoons, the Scots Greys, as they galloped into the Russian throng, their bearskins visible above the multitude. Then, to the amazement of the British, the Russians began to falter. The staggered charge of the different regiments had had the effect of landing repeated hammer blows on the enemy. Some well-placed shots from the Marine batteries further unsettled the Cossacks at the rear. ‘Yet another moment and the enemy’s column was observed to waver, then break, and shortly the whole body turned and galloped to the rear in disorder’, reported Shadwell.39 As the Russians rode pell-mell back down the Woronzoff Road, the guns of the Royal Marines, of Captain Barker’s battery and C Troop the Royal Horse Artillery hounded them. But the one mounted corps which could have pursued them stayed rooted to the spot. Throughout Scarlett’s charge, Lord Cardigan, who had made it from his yacht to shore, stood with his Light Brigade not 500 yards away. He was not about to advance without specific orders, and he had received none.

Notwithstanding Cardigan’s inertia, the most madcap cavalry charge of the war (so far) had, against all the odds, beaten back the vastly superior Russian squadrons. ‘There never was an action in which English cavalry distinguished themselves more’, claimed Lucan.40 Scarlett’s men could hear the Highlanders’ cheers from across the valley. Campbell rode up to the Scots Greys to congratulate them. ‘Greys! Gallant Greys! I am sixty-one years old,* and if I were young again I should be proud to be in your ranks’, he declared.41 Now that Campbell’s repulse of the Russians had been so ably followed up by Scarlett’s charge, Raglan realised that what had started as an unstoppable enemy offensive was turning to his advantage. The Russian cavalry had retreated behind the safety of their guns at the east end of the North Valley, but their artillery still commanded the Causeway Heights. Raglan wanted them back. After conferring with Campbell, Rustem Pasha tried to occupy Redoubt No. 5 with 200 Turks, but was prevented by the Russian guns on the Fedioukine Heights. Nevertheless, Cambridge’s infantry and the French 1st Division were closing in, while the Chasseurs d’Afrique, were bearing down on the Fedioukine Heights, and so Raglan sent Lucan the following order: ‘Cavalry to advance and take advantage of any opportunity to recover the Heights. They will be supported by the infantry, which have been ordered advance on two fronts.’** Lucan assumed Raglan meant he should advance once the infantry arrived to support him, but when the troops showed up they sat down and piled arms.

Three-quarters of an hour slipped by. Raglan was sure he could make out Russian horse artillery removing British guns from the redoubts. ‘We must set the poor Turks right again, [and] get the redoubts back’, he muttered.42 He asked Airey, his quartermaster-general, to send Lucan another order: ‘Lord Raglan wishes the cavalry to advance rapidly to the front – follow the enemy and try to prevent the enemy carrying away the guns. Troop Horse Artillery may accompany. French cavalry is on your left. Immediate. Airey.’

Few man-made disasters are the result of one action, or one individual, but rather a terrible conflagration of errors. That Airey handed this convoluted but vague order to Captain Nolan to deliver was another fateful twist. Nolan was a renowned horseman, in no one’s estimation more than his own, and he seemed the obvious ADC to hurtle down the rough slope from the Sapoune Heights to Lucan in the plain below. ‘A brave cavalry officer, doubtless,’ wrote Paget, ‘but reckless, unconciliatory, and headstrong, and one who was known through this campaign to have disparaged his own branch of the service, and therefore one ill-suited for so grave a mission.’43

When Lucan received the scribbled note from Nolan, he was confused. From his position he could see neither enemy nor any guns being removed. As he reread the note, searching for some hidden meaning, Nolan became frustrated. He had risked his life and that of his horse in a mad dash to get the order to Lucan, and yet his Lordship was wasting valuable minutes.

Raglan’s instructions often read like an apologetic school chaplain asking for missing kneelers, so, having grown used to a less didactic tone, Lucan bridled at an order ‘more fitting for a subaltern than for a general to receive’. He turned to Nolan and ‘urged the uselessness of such an attack’.

‘Lord Raglan’s orders are that the cavalry should attack immediately’, Nolan replied peremptorily.

‘Attack sir! Attack what and where? What guns are we to recover?’ asked Lucan.

‘There, my Lord!’ shouted Nolan, accompanying his words with a sweep of his hand. ‘There, my Lord, are your guns and your enemy!’***

Without further explanation offered by Nolan, or requested by Lucan, Nolan rode off. Lucan could see the Russian cannon drawn up at the far end of the North Valley, but it was against all the principles of warfare for cavalry to charge artillery. Nevertheless, he rode over to Cardigan and gave him the new order. Cardigan asked whether Lucan was aware that his cavalry would be fired upon in front and in flank. Lucan replied he did, but Raglan was insistent. ‘Having decided, against my conviction, to make the movement, I did all in my power to render it as little perilous as possible’, Lucan later claimed, feebly.44

From the Sapoune Heights, Raglan could see Cardigan’s Light Brigade moving into position, with the Heavy Brigade behind. All seemed well. Cardigan would advance a short way down the North Valley before wheeling to the right to stop the enemy making off with the guns from the redoubts. The Russians were of the same mind. The Odessa battalions on the Causeway Heights pulled back and formed square.

Cardigan led the brigade, slowly at first, but gathering speed. ‘There was no one, I believe, who, when he started on this advance, was insensible to the desperate undertaking in which he was about to be engaged’, wrote Paget.45 ‘We had not advanced two hundred yards before the guns on the flanks opened fire with shell and round shot,’ remembered Lieutenant E. Phillips of the 8th Hussars, ‘and almost at the same time the guns at the bottom of the valley opened.’46 As the Russian artillery started booming, Captain Nolan, who had permission to accompany the charge, galloped forward ahead of the line, towards Cardigan, gesturing and shouting furiously, but amid the pounding crash of the guns, Cardigan could not make out what he was saying.* All of a sudden Nolan’s voice changed to a blood-curdling screech as a shell splinter struck him in the heart.

Private Lamb of the 13th Hussars recalled:

We still kept on down the valley at a gallop, and a cross-fire from a Russian battery on our right opened a deadly fusillade upon us with canister and grape, causing great havoc amongst our horses and men, and mowing them down in heaps. I myself was struck down and rendered insensible. When I recovered consciousness, the smoke was so thick that I was not able to see where I was, nor had I the faintest idea what had become of the Brigade.47

‘One was guiding one’s own horse so as to avoid trampling on the bleeding objects in one’s path,’ explained Paget, ‘sometimes a man, sometimes a horse … The smoke, the noise, the cheers, the groans, the ‘ping ping’ whizzing past one’s head; the ‘whirr’ of the fragments of shells … what a sublime confusion it was! The ‘din of battle’- how expressive the term, and how entirely insusceptible of description!48

As the Light Brigade drew level with the Russians on the Causeway Heights, yet still showed no sign of turning right to attack, the gradual realisation of Lucan’s intentions dawned upon Raglan, and the enormity of the error. ‘We could scarcely believe the evidence of our senses!’ reported Russell. ‘Surely that handful of men are not going to charge an army in position?’49 The staff on the Sapoune Ridge watched, horrified, hoping Cardigan would turn back. Behind him, the Heavy Brigade had already suffered more casualties than in their earlier charge, so Lucan halted them and pulled back the forward regiments. The Light Brigade, meanwhile, rode on.

Up front and unscathed, Cardigan had by now ridden nearly the length of the valley, but as his horse covered the last few yards, twelve Russian guns ahead fired one mighty, earth-shaking volley. The earl, momentarily unnerved, recovered his composure and rode on through the battery. Beyond were ranged hundreds of Cossacks, who surrounded Cardigan. They were under orders to take him alive, but fighting common soldiers was beneath Cardigan’s dignity so, without raising his sword, he forced his way through and back down the valley.**

The rest of his brigade was not so circumspect. As the remnants of the Light Brigade reached the guns, they were seized by fury towards the men who had inflicted such a barbarous onslaught. So frenzied was the British assault, their rough sword hilts left sores on the troopers’ hands from all the hacking. Terrified Cossack artillerymen were reduced to defending themselves with whatever they could grasp, even the gun ramrods. It was anger borne of desperation. British prospects were grim: ‘We were a mile and a half from any support, our ranks broken (most, indeed, having fallen), with swarms of cavalry in front of us and round us’, explained Paget. ‘The case was now desperate. Of course, to retain the guns was out of the question.’50 In Cardigan’s absence, Paget decided that they had done all that honour required, but by now Russian lancers had swept in behind to cut off their retreat. ‘Helter-skelter then we went at these Lancers as fast as our poor tired horses could carry us’, he wrote:

A few of the men on the right flank of their leading squadrons, going farther than the rest of their line, came into momentary collision with the right flank of our fellows, but beyond this, strange as it may sound, they did nothing, and actually allowed us to shuffle, to edge away, by them, at a distance of hardly a horse’s length.51

‘From this moment the battle could be compared to a rabbit hunt’, observed General Ryzhov.’Those who managed to gallop away from the hussar sabres and slip past the lances of the Uhlans, were met with canister fire from our batteries and the bullets of our riflemen.’52 ‘I had not gone far when my mare began to flag,’ recalled Lieutenant Phillips. ‘I think she must have been hit in the leg by a second shot, as she suddenly dropped behind and fell over on her side. I extricated myself as quickly as possible and ran for my life, the firing being as hard as ever.’ ‘Sergeant Riley of the 8th was seen riding with eyes fixed and staring, his face as rigid and white as a flagstone, dead in the saddle’, wrote Phillips. ‘Sergeant Talbot of the 17th also carried on, his lance couched tightly under his arm, even though his head had been blown away.’53 ‘What a scene of havoc was this last mile,’ Paget lamented, ‘strewn with the dead and dying, and all friends! Some running, some limping, some crawling; horses in every position of agony, struggling to get up, then floundering again on their mutilated riders!’54

Amid the carnage were vignettes of bathos. A small terrier joined the charge and, though wounded twice, survived. Lieutenant Chamberlayne, his horse shot, and knowing the value of a good saddle, ran back down the valley with it perched on his head. The Russians assumed he was a looter from their side, and let him pass. The regimental butcher of the 17th Lancers, on a charge for drunkenness, heard the commotion in the valley below and, somewhat the worse for rum, ran down and grabbed a riderless Russian horse. Still dressed in his bloody overalls from slaughtering cattle the day before, and armed only with an axe, he joined the charge, killing six Russians in the main battery. On his return he was arrested for breaking out of a guard tent when confined thereto. Lucan let him off the court martial.

Though The Times claimed not only that ‘The blood which has been shed has not flowed in vain’, but that ‘Never was a more costly sacrifice made for a more worthy object’,55 Raglan’s nephew recognised the truth – that the Light Brigade had been ‘uselessly sacrificed’ and that ‘the results do not at all make up for our loss’.56 ‘It will be the cause of much ill-blood and accusation, I promise you’, Paget predicted. Sure enough, despite the ambiguity of his orders, Raglan blamed Lucan for not exercising his own judgement. Lucan in turn held Cardigan responsible for the same reason, while Paget was of the opinion that Nolan had been ‘the principal cause of this disaster’.57 Initially the scale of the blunder did not seem historic. ‘These sorts of things happen in war’, Airey told Lucan, ‘it is nothing to Chillianwala’. ‘I know nothing about Chillianwala’, replied Lucan, before assuring Airey, ‘I tell you that I do not intend to bear the smallest particle of responsibility.’58 Raglan made him the whipping boy anyway. ‘From some misconception of the instruction to advance, the Lieutenant-General [Lucan] considered that he was bound to attack at all hazards’, Raglan declared in his official despatch. Privately he told the Duke of Newcastle that ‘Lord Lucan had made a fatal mistake’.59 ‘Lord Lucan was to blame,’ agreed the queen, ‘but I fear he had been taunted by Captain Nolan.’60

Russell had witnessed all three actions: the Thin Red Line, the Charge of the Heavy Brigade and the Charge of the Light Brigade. As a narrative, the futility of Cardigan’s assault needed the balance of a palpable triumph. The Heavy Brigade had performed an extraordinary feat, but it was the bluff stoicism of the Highlanders that would play best with the public, the contrast of infantry and cavalry, of raw Celts and foppish troopers. In an age of steel-engraved illustrations, it was also a good deal easier to depict a line of immoveable Highlanders than the chaos of a cavalry charge. Russell knew his readers wanted something affirming the moral superiority of the British soldier. The Thin Red Line was ideal. It chimed with the British self-image: stoic, stalwart, stiff-upper-lipped. And so, again, Campbell was selected as protagonist.

Since he arrived in the Crimea, Campbell had shown a remarkably sophisticated understanding of the power of the press. As one officer writing in 1945 observed, ‘Sir Colin Campbell seems to have been several generations ahead of his time in his appreciation of the value of publicity as a stimulus to morale. From this point of view he might perhaps be described as the Montgomery of the Crimea.’61 Not just for morale, for personal advancement too. Campbell realised the importance of keeping correspondents like Russell on side, unlike Raglan. ‘A very small dose of civility from Lord Raglan would have tamed and made a friend of him; but they have, on the contrary, done all they could to insult him’, Sterling later wrote.62 Meanwhile, for Campbell, charming Russell now paid a bumper dividend. The rest of the press followed Russell’s lead. On 19 November, the day after Russell’s account appeared in The Times, Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper dubbed Campbell ‘the real Scottish lion’. Once more he was cast as the brave clansman, dour, doughty and speaking in that ludicrous ‘Hoots, mon’ Scottish vernacular which only exists in the English imagination. Added to the reputation won at the Alma, Balaklava now elevated him to the status of national hero.

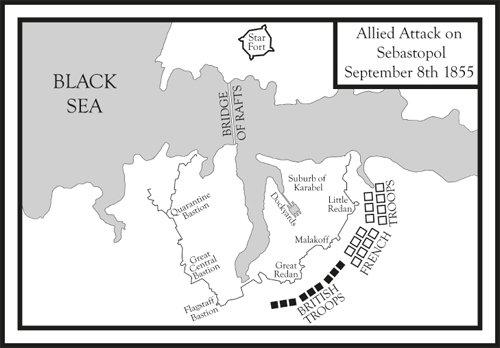

By the close of what remains one of the most dramatic days in British military history, Campbell had more important problems than his media profile. Cathcart had taken the two most westerly redoubts (nos 5 and 6) but, together with Campbell and Canrobert, felt the British position was overextended. All three urged Raglan to pull back and reinforce the inner ring of defences around Balaklava. Raglan agreed that the redoubts must be abandoned, although with the Russians in possession of the only proper metalled road to Sebastopol, all supplies would now have to be dragged up the rough track which led north-west from Balaklava to the Sapoune Ridge.

Campbell expected another Russian attack. ‘They may break through there this night’, he warned Sir Edward Colebrooke.63 He deployed the 93rd around No. 4 battery. The rest of his Highland Brigade, who had marched down with the Guards, stayed to strengthen Kadikoi, along with a French brigade under General Vinoy.* Those not on guard slept with loaded rifles. Campbell paced the battery until morning, impressing upon his men that, if need be, it was the duty of every soldier to die at his post. When day dawned, the Russians remained at a distance.

The battle so shook Raglan that two days later he ordered Campbell to evacuate the batteries on the Marine Heights and ship out the guns, but after appeals from Admiral Sir Edmund Lyons, Colonel Gordon of the engineers and the Commissary-General, Raglan changed his mind. Balaklava was cleared of all but critical shipping, and on 27 October HMS Sans Pareil moored in the harbour to provide extra protection. Meanwhile, at Kadikoi Campbell strengthened his position still further. Trous de loup** and abatis*** proliferated, and every tree was cut to within 3ft of the ground to deny the enemy cover. In the dip between No. 4 battery and the Marine Heights, he built a dam to create a shallow pond concealing a deep underwater ditch, invisible to the enemy. His troops’ love of the Highland Charge prevented them from wholly entering into the spirit of these elaborate defences. When Campbell complained that trenches dug by the 42nd and 79th were too shallow, one of the men replied, ‘If we make it so deep, we shall not be able to get over it to attack the Russians.’64

Campbell’s tendency to worry increased with his grey hairs, and by now he was permanently tense. Up on the heights he demanded the Marines maintain a constant vigil through ships’ telescopes, sending regular reports by runner or semaphore. He might have been, as Colebrooke noted, ‘all life at the prospect of action’,65 but he barely slept, checking and rechecking every order, unceasingly inspecting the defences and improving them. Campbell preferred to keep his headquarters at the crux of the line, No. 4 battery, rather than set up house in Balaklava: ‘I have sufficient anxiety in my front without wishing to add to it by seeing what I have behind me.’****66 The shortage of reliable troops was a great concern. Though he still had Rustem Pasha’s Turkish battalions, his faith in them had been shattered. ‘They take me by the shoulders and put me into Balaklava and try to defend it without any means, with a lot of Turks who run at the first shot’,67 he complained. Sterling’s view of them had changed from ‘capital fellows’ to ‘worse than useless’. ‘We have put the Turks in the rear, feeling sure that if we did not so place them, their natural modesty would soon take them there’, he noted.68 This left the perimeter woefully undermanned. Speaking of these days, Campbell later admitted that he held the lines ‘by sheer impudence’.69

With winter drawing in, the Russians were eager to lift the siege. On 2 November, fire from Russian howitzers on the eastern end of Campbell’s line seemed to herald an attack, but the enemy stayed put. A rainy 4 November left the ground next morning shrouded in thick fog, allowing the Russians to take the British by surprise. Their goal was Mount Inkerman outside Sebastopol, high ground which offered a commanding line of fire on the allies. Campbell heard the crash of battle in the distance, but it was not until later that afternoon that he learned the British had won an arithmetic victory. Russian losses were estimated at between 10,000 and 20,000, compared with only 2,600 British casualties, but as Henry Layard observed, echoing Dalhousie after Chillianwala, ‘Another such victory would be almost fatal to us.’70 ‘It was a great pity we had not the 42nd, 79th and 93rd Highlanders with us,’ commented one soldier, ‘for we knew well they would have left their marks upon the enemy, under the guidance of their old commander, Sir Colin Campbell.’71 ‘It was a disgrace to all the staff concerned that we were caught napping by an enemy whom we allowed to assemble close to us during the previous night without our knowledge’, complained Wolseley. ‘Had any general who knew his business – Sir Colin Campbell for instance – been in command of the division upon our extreme right that Gunpowder Plot Day of 1854, we should not have been caught unawares.’72 Absent at Inkerman, Campbell’s reputation remained intact and, if anything, enhanced. Augustus Stafford, MP, visiting the Crimea that autumn, confirmed that the man ‘in whom the army seem to have the greatest confidence is Sir Colin Campbell’.73

Though costing the Russians dear in men, Inkerman was a crushing blow to British morale. Sterling gloomily summed up their position: ‘We are besieging an enemy equal to our own in numbers, with another superior one outside and threatening us continually … The matter looks graver every day; a duel à mort with despotism requires numbers as well as bravery.’74 Two days after Inkerman, Raglan held a council of war. He decided to dig in and wait for reinforcements. Shocked at the thought of over-wintering, 225 of the 1,540 British officers simply left, many of them forced to sell their commissions at a loss.75

By 12 November, Campbell had received an extra 500 Zouaves and a detachment from the 2nd Battalion, the Rifle Brigade, but conditions for the troops were deteriorating. They had been in the same kit for months and everyone was covered in lice, even the Duke of Cambridge. The government agreed to issue every soldier with an extra uniform, but not until 1 April 1855. In the interim, men paraded wearing trousers made of sacking. Others turned out in trousers and a kilt, with a blanket on top, then a greatcoat and a further blanket wrapped round the shoulders. ‘All pretensions to finery or even decency are gone’, explained Sterling. ‘We eat dirt, sleep in dirt, and live dirty.’76 ‘Even the ground within our tents was trodden into mud,’ recalled Surgeon Munro, ‘and there we sat and slept, and fortunate was he who could secure a bundle of damp straw of which to make a bed.’77

Their Crimean hell had barely started. Two days later a cataclysmic storm broke. ‘We had just got our morning dose of cocoa, and the soldiers their rum, when, about seven o’clock, the squall came down on us’, recalled Sterling. ‘All the tents fell in about three minutes.’ ‘The Marines and Rifles on the cliffs over Balaklava lost tents, clothes – everything’, reported Russell. ‘The storm tore them away over the face of the rock and hurled them across the bay, and the men had to cling to the earth with all their might to avoid the same fate.’78 Twenty-one ships were wrecked, taking with them 10 million rounds of ammunition, twenty days’ forage for the horses, and 40,000 winter uniforms. On his yacht in the harbour, Cardigan was mildly sick. Raglan called in Commissary-General Filder and demanded that he send out officers to secure supplies ‘at any price’, while requesting the Duke of Newcastle send replacement shipments with the utmost urgency.79

The losses wrought by the storm placed an intolerable strain on an army supply chain already saddled with incompetence. Only in late September did anyone realise the army had headed out without candles. It had oil lamps and wicks, but no oil. Iron beds were sent to Scutari while their legs ended up in Balaklava. Petty jealousies and an absence of common sense pervaded every arm of the services. Departmental demarcation was sacred: the commissaries insisted that rations for Campbell’s Marines were an Admiralty matter and refused them food. Vegetables, meanwhile, had to be paid for ‘as articles of extra diet’. These shortages fell hardest on the men. ‘The officers, of course, are not suffering actually quite so much,’ wrote Sterling, ‘though quite as much in proportion to their previous habits.’80

The fuel ration was pitiful* and firewood so scarce that soldiers dug up roots or stole gabions** and pickaxe handles from the engineers. One night, Surgeon Munro was summoned to see Captain Mansfield, Campbell’s extra ADC, at his headquarters. Munro had not eaten because his servant could find no firewood. Spying a pile of logs, the surgeon asked if he might take one but Mansfield refused, so Munro waited until Campbell’s staff were in conversation, chose a large log and stole off with it. As he struggled back through the mud he heard footsteps behind him getting closer, until eventually a hand clapped him on the shoulder. Turning round, he saw Campbell’s batman with another log. He told Munro that if he was desperate enough to steal one from under the chief’s nose, his need was great indeed.81

Aside from cold and hunger, the other major threat was disease. Despite a reinforcement of 1,400 Turks towards the end of November, Campbell’s garrison was being gradually consumed by sickness. It had reduced the effective strength of the 1,200 Marines outside Balaklava by 300 men. They had just two medical officers, who had to wade through 3 miles of mud to make their rounds, working from 9 a.m. until 7 p.m. and then staying on duty throughout the night for emergencies. he only drug available was alum, supplied as a powder which the doctors had to make up into pills themselves. The church at Kadikoi was turned into a makeshift hospital for the men but ‘was always filled to overcrowding … the poor fellows lay packed as close as possible upon the floor, in their soiled and tattered uniform, and covered with their worn field blankets’ (see Plate 16). The spacious twenty-room home of a Russian lawyer was commandeered for sick officers and an old priest’s dwelling for the very worst cases. According to Munro, often all that was needed was warmth and food, but there was none available: ‘All that could be done was to lay them gently down and watch life ebb away.’82 There was scant incentive for prophylactic measures. As Munro explained, his ‘duties were to cure disease, not to make suggestions to prevent disease’.83 Then there were the ever-present financial constraints. ‘A more devoted set of men than the regimental surgeons, I never saw,’ wrote Sterling, ‘but they have been brought up all their lives under the tyranny of the Inspector-General, whose object it is to please the Government by keeping down the estimates.’84 The doctors were further hamstrung by their own bloody-minded supply office, the Purveyor. ‘If I had a knife and a piece of wood, it would be shorter and easier for me to make a splint than draw one from the Purveyor’, complained one surgeon.85

At least the agony of Balaklava forged a new bond between Campbell and the Highlanders, as Munro explained:

He was of their own warlike race, of their kith and kin, understood their character and feelings, and could rouse or quiet them at will with a few words … He spoke at times not only kindly, but familiarly to them, and often addressed individuals by their names … He was a frequent visitor at hospital, and took an interest in their ailments, and in all that concerned their comfort when they were ill. Such confidence in, and affection for him, had the men of his old Highland brigade, that they would have stood by or followed him through any danger. Yet there never was a commanding officer or general more exacting on all points of discipline than he.86

Within a few weeks the track from Balaklava had become a quagmire, and there wasn’t enough fodder for the pack animals. The solution was to corral Campbell’s men into fatigue parties, work despised by the Highlanders. Munro saw how:

So many loose shot or shell were placed in a field blanket, and two or four men, grasping the blanket by the corners, swung the load along between them. Many of the men preferred slinging the loads over their backs, and staggering along under the weight of two or more shot … The results of this duty were severe bowel complaints, fever, aggravated scorbutic symptoms and often cholera’,87

‘An army of this size in India would have with it 30,000 camels for transport’, protested Sterling. ‘I believe we have here in this place about 150 mules.’88 The situation reached such a crisis that when the 18th Foot landed it was decided the regiment would stay at Balaklava as porters.

‘How any man who had served under the Duke of Wellington, or who had even read his despatches, could ever have allowed such a state of affairs to arrive, is, to me, incomprehensible’, fumed one colonel.89 Raglan’s apologists excused his problems as an inevitable product of the system. The United Service Journal claimed that ‘From all we can learn, there appears to be no incompetency to individuals, the whole fault arises exclusively from the organisation.’90 Karl Marx, in the New York Times, claimed ‘the terrible evils, amid which the soldiers in the Crimea are perishing, are not his [Raglan’s] fault, but that of the system on which the British war establishment is administered’.91 But, as Ellenborough told the House of Lords on 14 May 1855, ‘To attribute everything to the defect of system is the subterfuge of convicted mediocrity.’92

There was nothing inevitable about the miseries of the Crimea. In China, Gough had encouraged his men to collect supplies as needed. His troops were always on the move, having to negotiate purchases in a language hardly anyone in the expedition understood, yet he succeeded. And while Gough was sourcing supplies locally, the Duke of Wellington was busy organising materiel from London, penning memos to the governor-general of India encouraging him to buy Chinese horses and hire carriage, or to employ junks as floating barracks and stables. In the Peninsula Wellington himself had slyly subverted the system by ordering far more corn than he needed and then selling the surplus, leaving him with cash to make up for deficiencies from Whitehall. Sadly, pre-empting the incompetence of his political masters was a measure alien to Raglan.

Fortunately for the Highlanders, Campbell did not wait for Raglan or the government to remedy the shortages. Wooden cabins had been promised for the men, but had yet to arrive, so Campbell set the men to digging a massive trench, roofed with planks, and overlaid with a layer of beaten clay, big enough to accommodate an entire regiment, near the crest of the hill outside Kadikoi. After only a few days, the soldiers inside were flooded out, and ‘Sir Colin’s Folly’ was abandoned.93 Unabashed, he next did what he knew had worked in the Peninsula: he ordered the men to build their own shelters, and to that end encouraged them to scavenge. Finding some soldiers building a hut and running short of wood, he suggested they take a mule and cart down to Balaklava to get more planks. When they asked where they might find a cart, Campbell replied, ‘Where would you get it? Why, man, off you go and seize the first mule and cart you can get hold of!’ Some while later the men returned with a wagon piled high with timber, pulled by an exhausted mule. On closer inspection, Campbell realised it was his own personal mule and cart.94

As Kinglake argued:

The capacity, the force of will, the personal ascendancy of officers commanding these several bodies of men, the zeal, judgment, the ability of the assistant commissary allowed to each division, the comparative number of men left in camp who might not be so prostrated by fatigue or sickness as to be incapable of hard bodily exertion – all these and perhaps many more were the varying conditions under which it resulted that deficiencies occurring in some parts of camp were from other parts of it wholly averted.*95

Campbell managed to alleviate many of those deficiencies and so his Highlanders had a better survival rate than most, but then as his brigade major wrote, he ‘has more experience in his little finger then the whole set up there [outside Sebastopol]’. Take food for example: officially, the British soldier was left to cook his unchanging rations himself. Campbell, however, realising the value in regimental kitchens, persuaded one of the Turkish commanders to send large copper cooking pots from Constantinople. It was a small advantage, but it was the sum of these little details which made the difference between a healthy regiment and a frail one. In any case, as a brigade commander he lacked the power to deal with anything beyond little details. As Sterling wrote on Campbell’s behalf in January 1855, ‘We, however, possess no power to remedy any radical error … we can only represent and lament.’96

Unlike some officers, Campbell resisted shaming the army into action. As in the Peninsular War, tales of failures relayed home by letter found their way into the newspapers, but he had no truck with such indiscretions. Campbell told Colonel Eyre:

The people of England have a right to expect a courage and endurance on the part of the officers of the army, which shall not yield to the discomfort unavoidable in a campaign carried on during the winter months, and that any little inconvenience they may be put to, shall be borne without the croaking and moaning they publish to the world. We have gone through some hardships, it is true, but nothing to justify the statements of officers that appear in the newspapers.97

Indeed, as Lord Stanmore pointed out, ‘Suffering was not greater, and the hospital accommodation, bad as it may have been, was far better than it had been in the forces engaged in the Duke of Wellington’s Peninsular campaigns.’98 The difference was that back in 1808 there hadn’t been much of a middle-class audience to gasp. The revelation of military incompetence in 1854 was nothing new, but this time the public were listening, and because so many more of them were enfranchised, the government took notice of their concerns. The status quo ante was not that no one knew about the problems in the army; it was that no one cared. In the past, the British soldier was an expendable drunkard. Now the middle class saw him as the last bulwark against foreign despotism. And as the common soldier was celebrated, so the blueblood generals were condemned. The didacticism of the aristocracy was discredited and there was a feeling abroad that things could be improved by individual effort. What better time for a self-made general to emerge? Campbell confirmed what the Victorian middle classes wanted to believe about their new society.

As reports of conditions reached Britain, so private organisations and individuals decided to right matters themselves. On 13 October 1854, The Times created its own Crimea Fund. In November, Florence Nightingale descended on Scutari with a cohort of nurses. That winter, Mary Seacole arrived in Balaklava to set up her own provision store and ‘hotel’ (an institution Nightingale believed was no better than a brothel). Isambard Kingdom Brunel designed a prefabricated hospital. Joseph Paxton, gardener, architect and designer of the Crystal Palace, recruited navvies to take on much of the logistical work. Samuel Cunard offered ships sufficient to carry 14,000 men to the front. These efforts were not just helpful in themselves, but of enormous benefit in embarrassing the authorities into activity.

The most famous chef of his day, Alexis Soyer, set about reforming the soldiers’ diet by introducing camp kitchens for mass meals, and new recipes to make the unimaginative rations palatable. ‘Exceedingly egotistical’, but with ‘all the marks of a great man in his own line’,99 Soyer invented a new stove (in use until the 1990s) to replace the charcoal ones that had caused carbon monoxide poisoning. He had intended to test his stoves on the Guards, but having landed at Balaklava and reported to the authorities, Soyer returned to find Campbell’s Highlanders had unloaded them and were already cooking on them.

The general public did their bit by sending food and clothing. ‘Old England is at last roused to a sense of our misfortunes,’ proclaimed one officer, ‘and is determined to atone for her dilatoriness by her liberality.’100 The drought soon became a flood. Fellow Scots sent the Highlanders ‘oat cakes and currant buns and bottles of whisky’.101 ‘All this is very kind … if they would only send plenty of horses and carts, and fat beeves for the soldiers’ dinners, it would be more use than a forest of hashed venison’, wrote Sterling after a consignment of potted deer arrived from the Marquess of Breadalbane, a man who had spent the past twenty years systematically ridding his estate of Highlanders.102 ‘The underclothing was in such superabundance that we could afford to make frequent changes,’ recalled Munro, ‘to put on new and throw away what we had worn only for a week or so, which, though new and good, and only soiled, it was considered too great a trouble to wash’. The 93rd even received a shipment of buffalo pelts. ‘These robes must have been expensive and I fear that the purchase of them was money thrown away’, wrote Munro, after finding they harboured lice.103

Campbell had too many worries to take much joy in the public’s largesse. Wellington held, ‘My rule always was to do the business of the day, in the day.’ Campbell, in contrast, continued his work round the clock and was soon close to collapse. His brigade major was little better. ‘I have looked in a looking-glass today for the first time since landing in the Crimea; my beard is getting long and grizzled, my face brown and healthy, my body thin, and my expression reckless and cynical.’104 On 28 November, after much persuasion, Campbell moved to a small house 150 yards from battery No. 4, which he had previously rejected as too far from the line. Here he had the space to unpack his luggage, which had been lying in the harbour, but he still insisted on sleeping in a tent outside. ‘Such was his anxious temperament, that he could not rest tranquil for a moment in the house’, remembered Shadwell. ‘A man coughing, a dog barking, or a tent flapping in the wind, was sufficient to startle him.’

Between 1 and 4 December, the sight of enemy officers just beyond the range of British guns, with a telescope so big it had to be supported on piled muskets, made Campbell more nervous still. Then on 5 December he noticed fires on the Causeway Heights near Redoubt No. 3. The Russian infantry had pulled back, taking their artillery with them and burning their huts as they went. ‘For the first time, that night Sir Colin lay down with his clothes off in the house’, recalled Shadwell, but even now Campbell could not relax completely, leaping out of bed in the small hours, mid-dream, and shouting ‘Stand to your arms!’ The Russians had retired to Tchorgoun, but that was still too close for Campbell. Helped by Turkish fatigue parties, the Highlanders strengthened their entrenchments still further, while Campbell roamed the lines urging vigilance at all times. Far from dreading these inspections, the men ‘vie[d] with each other in their endeavours to gain his approbation’. His ‘watchful energy was very different from that restless fussiness which is so often mistaken for it’, wrote Shadwell.105

With the Russian threat diminishing, disease remained the most pressing menace throughout December. By 1 January 1855, boosted by reinforcements, the British army stood at 43,754 men, yet only 23,634 of these were fit for duty. Campbell’s old regiment, the 9th Foot, had ‘sickened so fast, that of men fit for duty after only a few days of campaigning, it had only a small remnant left’.106 War eroded the high command as much as the ranks. Cathcart had been shot dead at Inkerman. A wounded Bentinck had been invalided back home. Cardigan had left on 5 December, citing ill health, and in late January Lucan received an ultimatum, stating that it was ‘Her Majesty’s pleasure that he should resign the command of the Cavalry Division and return forthwith to England’. In addition, the Duke of Newcastle was eager for Raglan to weed out the old guard, in particular Airey, Estcourt, Filder and Burgoyne.

The Duke of Cambridge was also ready to leave. He had found a new reservoir of courage at Inkerman, holding his position until down to his last 100 men, but he was never the same again. The Guards’ continued enfeeblement from disease left him ‘very nearly crazy’, in the words of one colonel, and war was straining his marriage. While the duke was recuperating from dysentery and typhoid fever on HMS Retribution, a thunderbolt hit the ship during the storm of 14 November and nearly sank her. ‘This was without any exception the most fearful day of my life’, he confessed. ‘I cannot ask you to stay’, wrote Raglan, ‘after … your sufferings from illness, anxiety of mind, exposure to the weather and over fatigue.’107 On 25 November, Cambridge boarded the Trent, bound for Constantinople.

Raglan now offered Campbell the choice of the 4th Division or the 1st Division if, as suspected, the Duke of Cambridge was gone for good. Careful to underplay his ambitions, Campbell said he would be happy to command either but would leave the decision to Raglan. A medical board declared Cambridge unfit, and so Campbell took over the 1st Division. As a bonus he was appointed Colonel of the 67th Foot on Christmas Day. His delight was only blunted by Raglan’s appointment of a new commandant for Balaklava. ‘C. [Campbell] is not responsible for the state of Balaklava’, wrote Sterling that January. ‘He does not command here. He thought he did, and began knocking the Staff officers about, and the new Commandant, for various misdeeds, when an order came out to place the troops under the command of the Commandant. Private interest with someone.’108 A general order from Raglan on 3 March, confirming Campbell’s command of all troops in and around Balaklava (aside from the cavalry), but allowing the commandant of the port to make requisitions ‘for such Duties and fatigues as may be necessary’, did not settle the matter.

Raglan himself had been promoted field marshal after Inkerman, but at home his reputation had soured. On Saturday 23 December, in the last editorial before Christmas, The Times savaged him:

The noblest army England ever sent from these shores has been sacrificed to the grossest mismanagement. Incompetency, lethargy, aristocratic hauteur, official indifference, favour, routine, perverseness and stupidity reign, revel and riot in the camp before Sebastopol, in the harbour of Balaklava, in the hospitals of Scutari, and how much nearer to home we do not venture to say … Everybody can point out something which should be done, but there is no one there to order it to be done … The period for good nature is over in the Crimea, and sterner qualities must be invoked into action.

Raglan was ‘invisible’, his staff ‘devoid of experience, without much sympathy for the distresses of the rank and file and disposed to treat the gravest affairs with a dangerous nonchalance’.109 As Adjutant-General James Estcourt sat down on 25 December to a dinner of roast goose and plum pudding, you might be forgiven for thinking they had a point. The government in London shared the paper’s doubts. As the Home Secretary, Lord Palmerston, wrote on 4 January, ‘In many essential points Raglan is unequal to the task which has fallen to his lot but it is impossible to remove him, and we must make the best of it.’110 Although, according to Surgeon-Major Bostock of the Scots Fusilier Guards, ‘everyone blames Lord Raglan very much’,111 Campbell was his staunch ally. ‘Never was a public Man more unjustly censured by the public’, he wrote.112 ‘I am disgusted with the attacks that have been made upon dear Lord Raglan. God pity the army if anything were to occur to take him from us!’113

In London support for Raglan continued to decline. At the end of January 1855, a Commons motion from John Roebuck, demanding a select committee examine the state of Raglan’s army, acted as a lightning conductor for discontent over the direction of the war. And the more diatribes and speeches condemned the old school, aristocratic command, the brighter shone Campbell’s halo. ‘Did they put him in command of a division?’ asked Liberal Henry Layard in the ensuing debate, ‘No! But in the command of a brigade, under a general officer who had never seen a shot fired, and knew nothing about a campaign.’114 The government lost by an embarrassing 148 votes. Next day, Prime Minister Lord Aberdeen resigned, replaced by the old political pugilist, populist and Russophobe, Lord Palmerston. The queen had desperately tried to persuade Lords Derby, Lansdowne, Clarendon and John Russell to take the job, but to no avail. As Palmerston put it, ‘I am, for the moment, l’inévitable.’

One of his most urgent tasks was rationalising the army. Lord Panmure was appointed Secretary for War and given the additional responsibilities of the Secretary at War.* In March he took control of the militia and the yeomanry from the Home Office. Authority over the Army Medical Department followed and, in May, control of the Board of Ordnance, while the remit of the commander-in-chief (Lord Hardinge) was extended to the engineers and the artillery. At last, the administration of the army was on a sound footing. The most important change of all had in fact already happened, when in December 1854 control of the Commissariat had been wrested from the Treasury and handed to the obvious trustee, the War Office.

Palmerston also wanted personnel changes. Raglan’s adjutant-general and quartermaster-general both had to go. A new chief of staff, James Simpson, took over their duties. His promotion to the local rank of lieutenant-general was backdated to August 1854, making him senior to Sir Richard England and Campbell,* and therefore heir apparent in the event of Raglan’s death. This was the second time Horse Guards had pulled this trick. When Bentinck had been gazetted lieutenant-general, his promotion was also backdated, to one day before Campbell’s. ‘It is really too bad’, complained Sterling. ‘Court influence: Quem deus vult perdere, prius dementat.’**

Despite this circumvention of his seniority, Campbell was on top form – optimistic, energetic, sure of British victory and with no semblance of the morbidity which had so often beset him in the past. ‘I have never enjoyed better health or more pleasant sleep’, he told his friend Colonel Eyre.115 There seems no obvious explanation for Campbell’s sudden buoyancy. The cabins promised for the men still languished unissued on the quay at Balaklava. Disease persisted. By the end of January, 12,000 British soldiers were still on the sick list.116 The enemy continued to bate him: on 6 January, four Russian infantry columns plus Cossacks approached the Marine Heights, but kept out of range of the guns, and between 7 and 10 February, the enemy threatened the Causeway Heights, but once again thought better of it.

Then finally, after the long winter stalemate, the allies declared themselves ready to push forward once more. The offensive would begin in the small hours of 19 February. Twelve thousand men under General Bosquet would advance and seize the Traktir Bridge. As a first step, Campbell, with 1,800 men and twelve guns, would take the high ground overlooking Tchorgoun before daylight, and then wait for the French. Bosquet’s task was to overwhelm the enemy’s right ‘while I went by myself to assail their left if possible’, as Campbell explained, ‘at any rate to hold it in check while the French were performing their part in the intended plan of operations’.*** ‘We were to move from our respective camps towards the enemy after midnight and I was to be at the place assigned to me at half past five in the morning, threatening the left of the enemy’s position’, but, wrote Campbell:

One of the most desperate snow storms I ever witnessed or experienced came on before I started. My route was across country in which there were no roads. No counter orders having reached me I marched at the ordered hour. Before my people got to the place of assembly, before marching off, four guns and five wagons got upset. The snow drifted in our faces, and the ground being covered with snow and the night dark, it was scarcely possible to make out the features of the country. Nevertheless we moved forward. I was urged to return or to wait for daylight, but that I would not do. I succeeded in stumbling upon and surprising a picket of Cossacks, their flight gave me the true direction and I got to my ground at a quarter past five.

Campbell’s determination was in vain. Perturbed by the weather, Bosquet had cancelled the offensive. Major Foley, ADC to Major-General Hugh Rose, had ridden out with orders for Campbell to retire, but had spent most of the night wandering around in the dark, before eventually stumbling into Raglan’s headquarters at 5 a.m. Raglan sent him out again with one of his own ADCs to make sure he didn’t get lost a second time. By now, Campbell’s brigade had been sitting on the Causeway Heights for several hours, believing they had 12,000 Frenchmen in support nearby, when all that time they had been quite alone. Luckily, as Campbell told Seward:

General Vinoy, a fine fellow, who is encamped near to my position here, seeing in the morning my people on the heights about six and a half miles off, at once concluded I might find myself with too many on my hands, for he knew the French had not gone out, and he started with three regiments to come and join me.

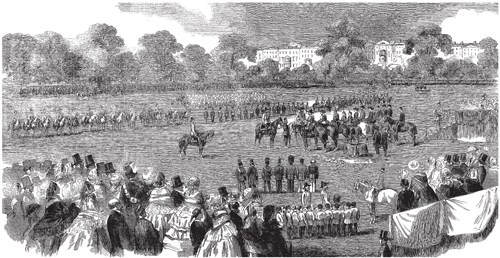

The whole pointless adventure had achieved nothing, except to leave many men with frostbitten fingers. Nevertheless, according to Campbell, ‘a good deal was thought of this march by Lord Raglan and the people at Headquarters at the time’, and it prompted a personal testimonial from the queen.117

By March, things were definitely looking up. Wood, charcoal and candle rations had all been increased and the death of the tsar on 2 March gave morale a fortuitous boost. ‘To the allies his death is a certain gain, as it is impossible to believe that his son will have his abilities’, wrote Sterling.118 As winter retreated, Campbell seemed full of the joys of spring. Running into him on 3 March, Paget described how he spoke ‘cheerfully of our prospects’,119 while another officer remarked how he ‘amused us much by his extreme vivacity and humour’.120 ‘The aspect of every thing here is much less sombre than it was during the Winter’, Campbell told the Duke of Cambridge. ‘The men are generally healthy and they are nothing near so much worked as they were … All the soldiers are in capital spirits.’121 What’s more, having suffered ‘the worst cook in the world, a very dirty Glaswegian soldier’, Campbell now received from General Vinoy a Monsieur Pascal Poupon as his personal chef. ‘Before his advent, our dinner was always a piece of mutton, when we could get it, stewed with French vegetable tablets’, wrote Sterling. ‘Now we have six dishes at least.’122

Everywhere were signs that the allies were gaining the upper hand, on their environment at least. A new railway stretched from Balaklava to Kadikoi and by 26 March had reached as far as Raglan’s headquarters, taking the strain off Campbell’s troops. Meanwhile, Colonel McMurdo, an old ADC of Charles Napier’s who had been with Campbell in the Kohat Pass, had arrived in the Crimea to institute a new Land Transport Corps and put a bit of stick about as regards the commissaries. Campbell still had his division digging and entrenching, but by now this was largely to keep the men occupied (see Plate 17). Confident in his defences, on 18 March he gave the men their first rest day since arriving at Balaklava. He was still twitchy enough to call all the troops out one night after hearing strange noises in the dip between Kadikoi and the Marine Heights, but it turned out to be an army of libidinous frogs, which amused General Canrobert enormously.123

Now that the basics of civilised life had been restored, boatloads of sightseers and officers’ wives began landing at Balaklava to hold picnics in between the skeletons – horse and human – in the North Valley or to watch the shelling of Sebastopol as the great second bombardment* began on 9 April. Though this barrage flattened the Russian Flagstaff bastion, once again it was not followed up by an assault. As the offensive faltered, so press interest waned. The mobile campaign of summer 1854 had given way to a long, tiresome war of attrition reliant on artillery and trenches, and with the scandals and shortages of the winter addressed, there was less for the newsmen to rail against. Punch, the previous autumn chock-full of the tsar, was now more interested in the new model dinosaurs in Sydenham. ‘Everyone was sick of the war,’ recalled Count von Eckstaedt, ‘but neither Russia nor the Western Powers could think of peace without incurring humiliation’.124

The temptation, when an army gets bogged down, is to try a new theatre. With stalemate at Sebastopol, Raglan suggested sailing east to take the port of Kertch, commanding the straits between the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, and thus cut off Russia from her Circassian provinces while gaining access for the allies to this inland sea. The French provided 8,500 men, the majority of the expedition.125 The 42nd, 71st and 93rd Highlanders were mustered to go, but, to Campbell’s surprise, Raglan chose Sir George Brown to lead them instead. Swallowing his pride, Campbell offered to serve under Brown but Raglan refused. One officer wrote:

You will hardly believe they send Sir G. Brown to command, and give him the Highland Brigade, taking it away from Sir C. Campbell, who has commanded it since he left England. The Highlanders worship him and would have fought twice as well under him as under anyone else … He will make a mess of it – he has not a general’s head on his shoulders as Sir C. C. has.126

‘I never saw C. so much vexed’, recorded Sterling:

There is no general here who has not been truer to Lord Raglan than C. He has uniformly defended him, not only because he thought him usually in the right, but also from a feeling that the proper soldier has of defending his general; and this is the way he treats him.

Barely had the expedition weighed anchor on 3 May than it was summarily recalled by Napoleon III. ‘My reading of it’, wrote Sterling, ‘is that the Emperor of the French is coming here to command the whole, and that he will not let the army be frittered away in petty enterprises’. However, following the resignation of French commander-in-chief Canrobert on 19 May, his replacement, General Pelissier, reinstated the Kertch operation. Two days late, the allies raised steam and spread canvas once again. As before, Sir George Brown led the Highlanders. ‘I am giving you good troops,’ Campbell told Brown. ‘I would as soon have my own,’ was Brown’s reply.127