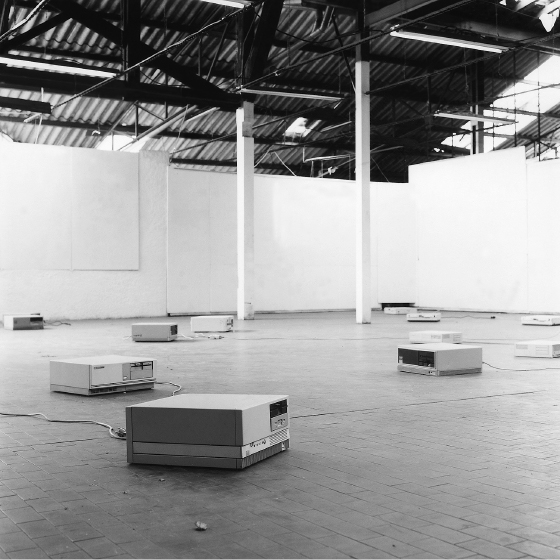

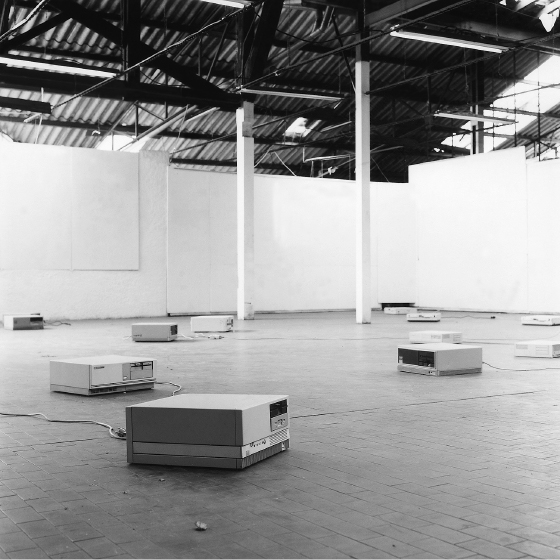

Figure 0.1 Maurizio Bolognini, Sealed Computers (Computer sigillati) (since 1992), installation view, Atelier de la Lanterne, Nice, France, 1997. Copyright © the artist.

My fascination with the aesthetics of machines began with a number of encounters. Maurizio Bolognini’s Sealed Computers (1992)—an art installation of desktop computers, networked, audibly running, yet without monitors, so that it is impossible to know what is being computed, or whether there is a conversation, or even a conspiracy, going on between them—has been the clearest example for me to explain what it is that got me interested in the topic (figure 0.1). The astonishment and irritation one feels about these machines’ autonomy; the impossibility of understanding what is going on; and this impossibility, this irritation, serving as the aesthetic hinge of our experience, forcing us to acknowledge the distance that we have as the audience of an artwork from something that unfolds right in front of our eyes, or in other cases perhaps even through our interaction—responses like these, in myself and in others, got me thinking about machines. Here are some other examples that can set the scene.

Figure 0.1 Maurizio Bolognini, Sealed Computers (Computer sigillati) (since 1992), installation view, Atelier de la Lanterne, Nice, France, 1997. Copyright © the artist.

The woman in the film touches the surface of a blimp tenderly (figure 0.2). She caresses the soft white material, it dents, and slowly moves away from her hand, restoring its full, round shape. It drifts upward, she follows it with her eyes, her hands half lifting it, half trying to stay in touch; don’t fly away!

Figure 0.2 Daria Martín, Soft Materials (2004), 16 mm film, 10 minutes 30 seconds, film still (female dancer with blimp). Copyright © the artist, courtesy Maureen Paley, London.

Some moments later the scene has changed: a man lies on the floor next to a robot and carefully touches its array of small pipes (figure 0.3). They move like a wave, and it is impossible to tell whether they are responding to his touch or whether he is following their mechanical movement. An intimate and oblique interaction.

Figure 0.3 Daria Martín, Soft Materials (2004), 16 mm film, 10 minutes 30 seconds, film still (male dancer with pipes). Copyright © the artist, courtesy Maureen Paley, London.

Three further scenes from Daria Martín’s film Soft Materials (2004) show the same man and woman with other apparatuses: the woman playing with her own long dark hair and with the whiskerlike hair of a small robot; the man holding a robotic hand that tenderly touches and squeezes his skin, he moves and positions the hand so that it can stroke his shoulder, his arm, his face; the woman standing, her torso bent down, making movements which mimic the simple robot next to her that is designed to jump up and down, waving two winglike elements.

In each of the scenes, the man and the woman are naked, which turns their encounters with the technical apparatuses into elemental events. They have been filmed in spaces that look like scientific research labs—not the most obvious sites of such intimate interplay, though the right places for the controlled observation of an encounter between different species. In the exhibition, the film is looped so that the sequence of scenes, each a few minutes long, repeats endlessly. Martín’s film presents the encounter between humans and technical apparatuses as an erotic adventure, playing on the voyeuristic desire of the viewer, as much as on the disconcerting existential difference between humans and machines, and the apparent indifference of the machines.1

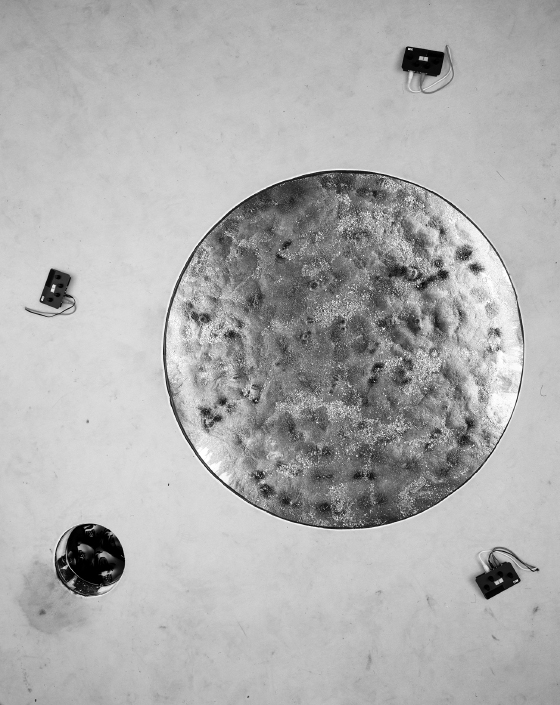

Let’s move on. Huddled on a large wooden platform which has been built into an exhibition space, some visitors gaze into a Plexiglas-covered terrarium. It is brightly lit, and inside is a shallow landscape of metal and other material granules (figures 0.4, 0.5). Heavy vibrations and sounds are emitted from the platform, a material drone sound that fills the entire space. The sounds are related to movements in the landscape of granules, to waves and eruptions which move through the material and which seem to be effected by magnets underneath the materials. As the magnets under different parts of the landscape are consecutively activated, portions of the materials that respond to the magnetism rise up in bizarre forms, wiggle, and fall back into passivity after passing on their energy, so it seems, to the neighboring materials. The patterns in which the magnets are activated can be manipulated by means of several MIDI controllers that lie on the platform. The visitors wrap themselves in industrial, if not infernal, noise while creating a weird, small-scale spectacle in the miniature desert.

Figure 0.4 Herwig Weiser, zgodlocator (2000), installation view, Trinitatiskirche, Cologne. Copyright © the artist.

Figure 0.5 Herwig Weiser, zgodlocator (2000), detail. Copyright © the artist.

The installation is Herwig Weiser’s zgodlocator (2000). It uses the granulated materials from recycled computer hardware that, when it has become redundant, is destroyed and ground up, after which the different materials are separated for reuse. From such postindustrial materials, Weiser has created the small landscape as a moving image of the afterlife of computers. It is here combined with an elaborate and somewhat massive technical installation that controls the activation of the matrix of magnets, including a large and heavy rack in a glass case, placed next to the platform, with separate units for each of the magnets.

If Daria Martín’s film is about the intimate encounter between humans and machines, and about both the tenderness and the strangeness of such an encounter, then Weiser’s installation suggests a scenario in which what remains of the machine after its dereliction, and what materially precedes it, is far from a form that could be addressed as a subject, as a partner, or as a counterpart. While the apparatuses in Martín’s laboratories can easily be mistaken for living or sentient entities that interact with their human visitors, Weiser confronts us with an environment which mobilizes a technical materiality that seems to lie both beyond and before its use as hardware. Additionally, Weiser’s work conveys the fascination of the artist working with such raw and heavy-duty stuff, the wonderment of the visitors bringing the granulated machine landscape to life, and my own captivation as I observe this scene of wonder.

It was experiences like these which made me want to investigate people’s relationships with machines as they have been articulated in twentieth-century art. This study rests on a foundation of artworks. In most cases, these have not been created in order to make a particular theoretical point, or to confound an argument, but they articulate specific, singular aesthetic positions and play on the margins of more general discourses about technology. This is therefore first and foremost a book about art, and an attempt at describing a certain engagement of artists with technical systems. “Machine art” is neither a particular artistic movement nor a genre of work, but rather a myth, or a rumor, that has been around for a hundred years, no more. The contemporary understanding of the “machine” is extremely diverse, and has changed in parallel with the development of technological systems. A question that motivated this research was whether the introduction of the computer led to a radical break in such conceptions, which would have resulted in a concomitant break in the artistic work on technology—or whether we can find continuities throughout the twentieth century that connect works made around 2000 to developments of the 1950s and 1960s, as well as to the avant-gardes earlier in the century. I was curious to see whether it was possible to elucidate the art historical lineage of works like those by Bolognini or Weiser, and how such a reconstruction would change the perspective on recent developments in the arts which imagine themselves primarily as driven by new media technologies.

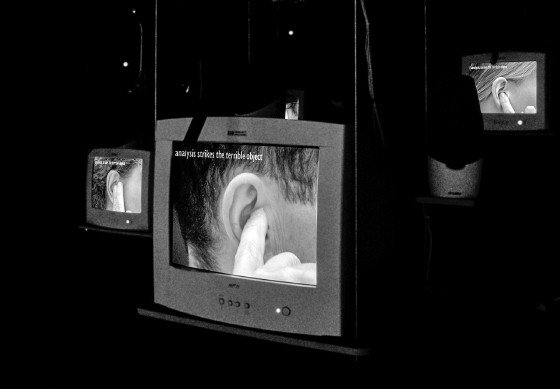

Besides the ambiguity of Bolognini’s installation, the robotic eroticism in Martín’s film, and the playful apocalypse in Weiser’s work, another aspect of the human encounter with technology is the confrontation with artificial and intelligent technical entities, staged in an exemplary fashion by David Rokeby’s installation n-cha(n)t (2001, figure 0.6). Upon entering the room, one hears several humanlike voices reciting a text in unison, like a choir. The text appears to be an open-ended meandering of English words, following syntactical rules yet in a poetic form that verges on the nonsensical. The calm recital comes from loudspeakers which are attached to an array of computers that hang in the space and are combined with flatscreen monitors. The monitors each show a part of a human head in profile, with the ear in the middle, surrounded by some centimeters of hair and neck, yet the face and any other individualizing features fall outside of the image frame. The most recent words that have been spoken appear as legible white text at the top of the monitor screen.

Figure 0.6 David Rokeby, n-cha(n)t (2001), installation view, Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for the Arts. Photo by Don Lee, Banff Center. Copyright © the artist.

There are microphones in front of the screens, inviting the human visitor to speak into them. When this happens, the respective computer unit interrupts itself and stops talking, on the screen a hand is raised and covers the ear, and the text display shows the words that a speech-to-text module in the computer has decoded from the visitor’s voice. These words are then integrated into the meandering discourse of this particular unit. In turn, this change also disturbs the discourse of the others, which appear to have been “listening” to their neighboring units. For a short while, the confusion of the voices builds up, each now reciting a different string of words. Yet, after some minutes, the different units resynchronize and gradually return to the unisonic chant, oblivious to any human presence, or interlocutors—until the latter reappear by speaking, yelling, or clapping in front of one of the microphones.

We will return to Rokeby’s work in chapter 3. For the moment, the two main aspects of the installation are the autonomous communality of the networked computers and the separation between their sphere and the sphere of human interlocutors. The programmed communication between the computer units gravitates toward a state of communal harmony and choral equilibrium so long as they are not disturbed by outside sonic intervention. The communication among the computers is taking place on a different channel—a hard-wired local area network—while the voice-based interventions of the human visitors are enabled by sound-sensitive microphones and a speech-to-text interface. Rokeby’s installation thus sets up the encounter between humans and machines not as one of intimacy or of utter material strangeness, but as an encounter that is both social and deeply antagonistic.