Paul – lead and

backing vocals, bass, piano

John – backing vocals, possibly guitar

George – backing vocals

Ringo – drums, chimes

Session musicians – two clarinets, bass clarinet

Possibly prompted by his father’s 64th birthday the previous July, Paul dusted off ‘When I’m Sixty-Four’ from the early pre-Beatle days as the first of his songs to be recorded for the new Beatles album (which at that stage was to have included ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’). That the album it ended up on was Sgt Pepper was fortunate, as it sits easily amongst the widely diverse tracks on the album, and would have nestled incongruously among the songs on any Beatles album up to Rubber Soul, or even on Revolver. In fact, the jokey, music-hall atmosphere evoked by the song and its arrangement complements tracks like ‘Mr Kite’ and ‘Lovely Rita’ which help to provide a firmly traditional setting for the album, making the avant-garde experimentation and studio gimmickry at the same time both remarkable and palatable. Its amiable nature also helped its successful transfer to the film Yellow Submarine, accompanied by Sgt Pepper tracks ‘Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds’ and ‘Sgt Pepper’ itself.

The song pre-dates Paul’s Beatle years, the essence of it having been written when he was about sixteen – he told George Martin that it was “possibly the first song I ever wrote on the piano”. In the days when the Beatles performed in the Cavern, the PA system frequently gave out. When this happened, they were compelled to fill in with acoustic numbers, including this one.

Having been written by a sixteen-year-old, albeit a sixteen-year-old Paul McCartney, the song naturally has fewer of the sophisticated aspects of other Sgt Pepper tracks. It nevertheless boasts a few worthy features. The C major verse, and relative A minor bridge, though not particularly inventive, work well. The harmonic shape of the piece is also well thought out, with the chords coming thicker and faster as the verse progresses. The melody consists of a good mix of triadic leaps (the bugle-call of “when I get older”) and chromatic slides (the twenties-style shuffle of “will you still be sending me a valentine”).

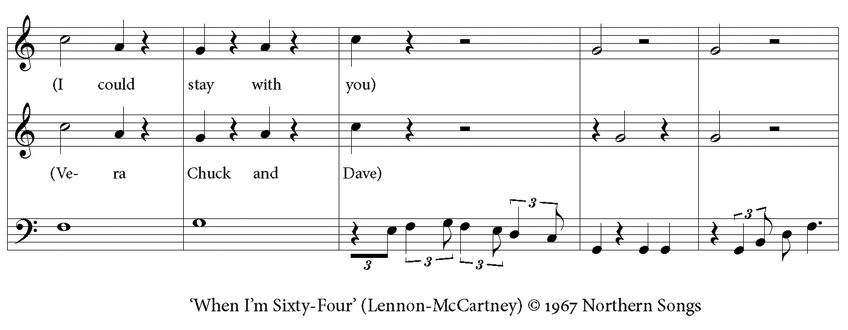

Although the song is absolutely not John’s style – he claims he “would never even dream of writing a song like that” – it does bear his fingerprints. If John would never dream of writing ‘When I’m Sixty-Four’, Paul would probably never dream of grandchildren languishing under the names of Vera, Chuck and Dave. John’s seemingly off-hand contribution captures the wit of the song and throws a surreal cog into the machine. Paul enters into the spirit with a wonderful low-key jokey Hibernian accent for “on yer knee”.

George Martin observes in Summer Of Love that beneath the song’s frivolity lies a message about Paul’s horror of the banality and tedium of growing old. Paul later denied this – “It wasn’t really, it was very tongue-in-cheek … a parody on Northern life. It’s like I’m writing a little play.” Nevertheless, the playback of the song is deliberately fast, sped up from the key of C to Db and thereby raising the pitch of Paul’s voice, so that 64 sounds a long way off. The snare brushing that gives a subtle hiss throughout the verses also helps to set the song in a period context.

That this track was the first Sgt Pepper song that the Beatles recorded is demonstrated by the use of its instruments. While the arrangements of the Sgt Pepper songs are, like most of the Beatles’ work, nearly always restrained and the instrumentation can sound open and uncluttered, the tracks actually were becoming increasingly layered and honed, with piano parts, harmonicas, guitars added. This was always done with subtlety, but nevertheless, very few of the tracks had simple arrangements (‘She’s Leaving Home’ being a notable exception). Now the Beatles had time and energy to devote to their music, and their collective imagination was not only unfettered by the hassle of touring but was also being fed by pharmaceutical stimulants. Tracks that would be completed in a matter of a day or two were becoming the exception. However, in stark contrast to ‘Penny Lane’, ‘When I’m Sixty-Four’ was still pretty straightforward as recordings go, with little added between the recording of the basic track and the overdubbing of the clarinets.

The first session was spent recording the basic rhythm track, with Paul overdubbing his vocal a couple of days later. This overdub was recorded in Studio One – George Martin had overdubbed the piano on ‘Misery’ here back in February 1963, and the Beatles had used it to tape promo films for ‘Paperback Writer’ and ‘Rain’ the previous May, but this was the first time any of the Beatles had recorded in Studio One. In fact, over 95% of the group’s recording took place in Studio Two, the massive Studio One being used primarily for orchestral recordings. It would be used again for the orchestral ‘A Day In The Life’ overdub of course, as well as the ‘All You Need Is Love’ event.

For today, no other Beatle was present for the recording of Paul’s ‘When I’m Sixty-Four’ lead vocal. Two sessions held just before Christmas saw backing vocals and the chimes added, the recording of the track capped by the overdubbing of the woodwind.

The restrained woodwind arrangement of the song has echoes of the brass orchestration on ‘Got To Get You Into My Life’, and the frivolous chimes look forward to the anvil of ‘Maxwell’s Silver Hammer’. The brilliant clarinet arrangement is another fine piece of George Martin scoring, written in response to Paul’s request for “a kind of tooty sound”. After stating the case with the lilting hook, the clarinets and bass clarinet are content to provide simple harmonic accompaniment, with delicate flourishes when Paul isn’t looking. The bass clarinet has a neat little figure before the bridge, and sneaks in for the carefree “go for a ride”. Having gained confidence, the last verse has a beautiful accompaniment from the woodwind, no flirting, just harmonic underscoring. George Martin later pointed out that the line “indicate precisely what you mean to say” was also how Paul felt about the scoring of a song. “Every note played had to be there for a purpose.”

The chimes are also used with control and they too work well. The subtle change in position of the clanging during the second bridge, whether deliberate or not, adds subtle interest (much more so than the heavy, plodding anvil in ‘Maxwell’). The syncopation of the second set of chimes adds to the off-beat surrealism of the Scottish grandchildren.

The clarinets break loose during the final verse and accompany the melody in thirds and fourths, with an appropriately downbeat emphasis to “wasting away”. Halfway through the verse, we become aware of a guitar that was not there before. It comes up briefly and distantly, again in a wonderfully appropriate laid-back folky style, and is possibly played by John. In Summer Of Love, George Martin seems to indicate that all John and George contributed to the song’s recording were backing vocals, but this might not include the final session in which Paul recorded the final lead vocal track. So although it is possible that Paul plays the guitar himself, it may be that John is accompanying Paul while he is singing. Whatever the case, something makes Paul smile on the final “will you still need me”, and it is a nice image to think that he is amused by John guitar style.

The carefree “hoo” that prefaces the last four bars provides a vanguard for the fun of ‘Lovely Rita’.