|

21 |

BABE RUTH AS PITCHING STAR AND CAR-BATTERING ACE |

Renowned as “the Sultan of Swat” for his prodigious home runs, Babe Ruth also was an ace on the mound. Many baseball historians insist that the man known as El Bambino could have remained a star pitcher—and future Hall of Famer because of that—without having to move into the outfield. How good was he as a twirler? Try this one on for size:

Once, the Babe tossed twenty-nine and two-thirds consecutive scoreless innings during World Series games.

Part of Ruth’s success was his control, which was more than could be said when he was behind the wheel of a car. Once, the Babe’s chroniclers noted, “Many a day the morning papers carried headlines about yet another custom-built car that Ruth had wrapped around a lamp post.”

|

22 |

THE MOST INCREDIBLE WORLD SERIES ALIBI |

Like other athletes, baseball players hate to lose.

Sometimes—as in the World Series, for example—losing is more painful than it is for a regular season game.

That might explain how Billy Loes uttered the most absurd rationale after blowing a World Series game to the New York Yankees. The lean Lanky Loes was admired for his droll, and occasionally bizarre, humor. His most widely played retort was delivered during the 1952 World Series when he mistook the velocity of a grounder to the mound and erred on the play. Questioned about the error, Loes replied with a straight face: “I lost it in the sun!”

A lesser but philosophically better line was delivered in Loes’ career. Many observers wondered why a pitcher with so much natural talent could continually fail to win more than fourteen games a season, even though he was backed by a strong club. When a reporter questioned Loes about his perennial failure to reach the twenty-win plateau, Billy mulled over the query for a moment and then rather candidly commented that such a Promethean effort would be damaging to his psyche: “If you win twenty,” said Loes, “they want you to do it every year.”

|

23 |

A YANKEES BATBOY WAS FIRED FOR ALMOST KILLING BABE RUTH—AND LATER BECAME A FILM STAR |

If these episodes didn’t actually happen, you might believe that a Hollywood scriptwriter made them up. Come to think of it, Hollywood is partially involved in this remarkable bit of baseball trivia.

When Babe Ruth was at the apex of his career, a robust young batboy worshipped “the Sultan of Swat,” and the Babe, in return, encouraged the young man to pursue a baseball career. The batboy in question was none other than William Bendix, and Babe’s very wish was Bendix’s command: the kid would shine the Babe’s shoes, run his errands, and provide Ruth with all the food the heavy-eating Babe would require.

One day before a game, Ruth dispatched Bendix to obtain some soda pop and hot dogs. Dutifully, the kid returned with a dozen frankfurters and several quarts of soda. As usual, Ruth, one of sportdom’s notorious trenchermen, devoured everything that Bendix delivered to the locker room.

This time the feast took its toll and, later in the afternoon, Ruth collapsed with severe stomach pains and was rushed to the hospital. Headlines across the country proclaimed that Ruth actually was dying. When the Yankees’ front office discovered that William Bendix had delivered the food to Ruth, the young batboy was summarily dismissed.

The Babe recovered and continued hitting home runs and drawing fans to every ballpark in the American League. Meanwhile, the brokenhearted Bendix abandoned his pursuit of a baseball career and, instead, turned to the theater.

Curiously, Bendix played hundreds of roles, many of them involving sports figures. One of his popular parts was that of “The Bambino” himself, in The Babe Ruth Story.

|

24 |

DOUBLE DUTY WAS HIS NAME; CATCHING AND PITCHING IN A DOUBLEHEADER WAS HIS CLAIM TO FAME |

The Pittsburgh Crawfords of the Negro National League certainly got their money’s worth from Ted Radcliffe.

To begin, Radcliffe was behind the plate for nine innings as the Crawfords went 5–0 in the first game of a doubleheader at Yankee Stadium.

In the second game, Ted took the mound and spun a 4–0 shutout. Talk about double dipping. As a result, Radcliffe earned the nickname “Double Duty,” thanks to journalist Damon Runyon.

After seeing Radcliffe perform, Runyon wrote, “It was worth the admission price of two to see Double Duty out there in action.”

Those who played with and against Radcliffe toasted his versatility. “He never got the recognition he should have,” said shortstop Jake Stephens. “In my book, he was one of the greatest.”

Added Catcher Royal “Skink” Browning: “Radcliffe could catch the first game, pitch the second–and was a terror at both of them.”

|

25 |

TWO BROTHERS WHO AMASSED AN ASTONISHING WIN TOTAL |

Baseball has been happily filled with amazing brother acts.

For example, the Cardinals won multiple World Series with Mort Cooper on the mound and his brother Walker behind the plate.

And earlier, Redbirds teams featured a pair of sterling pitchers, the brothers Dizzy and Daffy Dean.

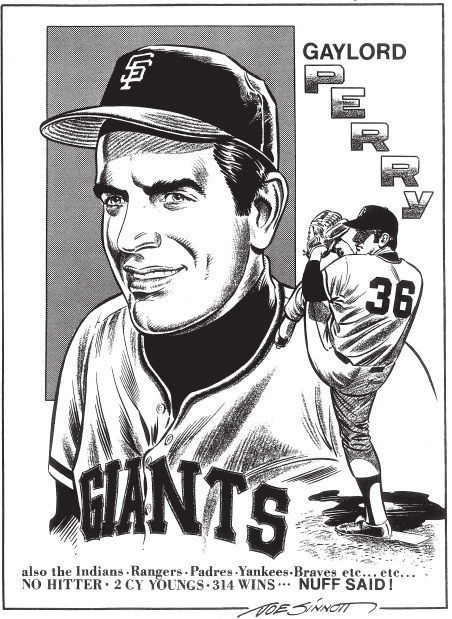

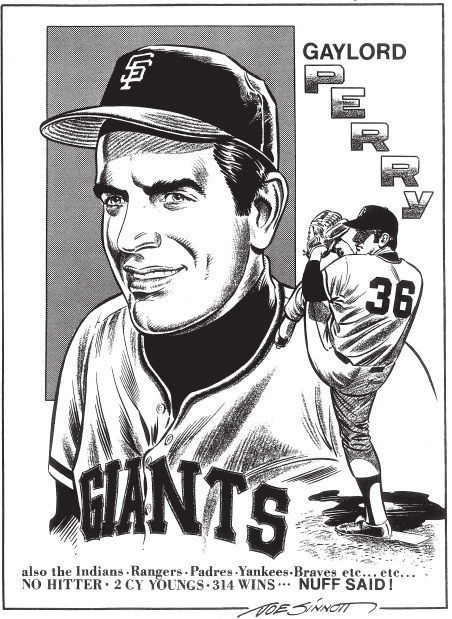

But when it came to victories, the Deans took a backseat to Gaylord and Jim Perry. Between them, they accumulated an amazing 529 victories.

The runners-up were the Mathewsons, Christy and Henry, who registered their second-place total of 373 while with the New York Giants in the early 1900s. There’s just one catch with the Mathewson brothers: Christy won all of those games! Henry Mathewson pitched for the Giants in 1906 and 1907, appeared in three games, and had one decision—a loss. Not much of a contributor.

The Perry brothers had a much more equitable distribution of wins. Jim had 215 wins, while younger brother Gaylord earned 314 wins. They did get the chance to play together for the Cleveland Indians in 1974 and 1975.

|

26 |

THE BEST PUT-DOWN OF AN AMERICAN PRESIDENT BY A BASEBALL STAR |

Normally, the president of the United States—no matter what the decade, nor political affiliation—is treated with the upmost respect by ballplayers. But when someone with the stature and humor of a Babe Ruth is concerned, all bets are off.

One president who made the discovery was the Republican Herbert Hoover.

The first year of the Great Depression, Ruth signed a contract for $80,000. The Yankees had rewarded him with the then-astronomical salary because of his popularity as a slugger and value to the team at the box office. Still, $80,000 was more than a lot of money; it was outrageous at that time.

At least that was the opinion of one sportswriter, who asked Ruth how it felt to earn more money than the president of the United States. Ruth, the inimitable Bambino, mulled over the question, realized how unpopular the president had become in those Depression days, and then shot back: “Well, I had a better year than he did!”

|

27 |

FROM PRISON TO THE MAJORS—THANKS TO BILLY MARTIN |

An old song, “If I Had The Wings Of An Angel–Over These Prison Walls I Would Fly,” depicts a fantasizing convict musing about his potential escape from the penitentiary.

It’s hard to determine whether Ron LeFlore had that tune in mind while an inmate in the Jackson State Prison.

Incarcerated on a five-to-fifteen-year sentence for armed robbery, LeFlore volunteered to play for the prison baseball team. In time, he became so good that fellow inmate, Jim Karella, began promoting LeFlore as a potential pro ballplayer.

That was the start of Ron’s good fortune. It multiplied when then Detroit Tigers manager Billy Martin visited Jackson State and began hearing—over and over and over again—about LeFore’s diamond talent.

As a result, the Tigers arranged for LeFlore’s furlough and a tryout at Tiger Stadium. It was more of a good will gesture than anything else.

But LeFlore surprised even the skeptics, and the Tigers signed him to a Minor League contract on July 2, 1973, the day he was paroled.

After playing less than one season in the minors, LeFlore was called up by the Tigers in 1974. He became a star for his hometown team, a plus-.300 hitter, and a mainstay on a young and aggressive team.

LeFlore’s story sounds good enough for a Hollywood scriptwriter, doesn’t it? Well, CBS-TV thought so and produced One in a Million, Ron’s life story starring LeVar Burton of Roots fame, as LeFlore.

Billy Martin was played by—who else?—Billy Martin. Said Burton of Martin: “He follows instructions like a little leaguer at tryouts. You know, Billy’s a pussycat, really. A pussycat with chutzpah.”

|

28 |

THE INCREDIBLE STORY OF A TEENAGE VENDOR WHO LATER RETURNED TO THE SAME FIELD AS A BIG LEAGUE PLAYER |

Eddie Glynn lived less than two miles from Shea Stadium when the ballpark opened in 1964. In 1967, he began working at the stadium as a vendor later. He would later return to play in the World Series as a member of the 1979 Mets.

Glynn recalled, “I wasn’t into the vendor tricks, like tossing peanuts and catching coins.” He was more intent on studying the styles of the various players.

In 1972, Glynn signed with the Detroit Tigers organization. He was traded to the Mets in 1979 for pitcher Mardie Cornejo.

Upon his return to Shea, Glynn remarked, “It was like a dream come true. I’d go around talking to the vendors and fans after the game. But it worked the other way, too. If I had a bad game, the fans would get on me. ‘Hey, Glynn, go back to selling hot dogs.’”

In May 1980, the Mets held a Hot Dog day and gave Glynn a hot dog vending tray with his number, 48, embossed on the side. Glynn responded by climbing into the stands and hawking hot dogs.

|

29 |

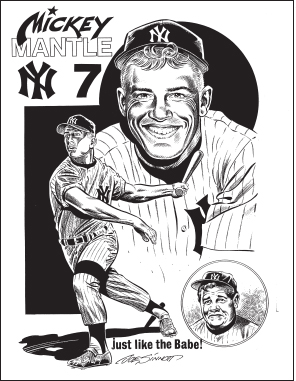

MICKEY MANTLE AND ROGER MARIS AS MOVIE STARS—IT HAPPENED IN HOLLYWOOD |

The Yankees sluggers were so popular in the early 1960s that film moguls decided to make actors out of them, at least for one film.

It’s called Safe at Home (1962) and is about a Little Leaguer. Simply put, the plot has the lad running away from home to the Yankees spring training camp, where he asks the outfield starters to appear at a Little League banquet.

|

30 |

ROOKIE MANAGERS ARE NOT SUPPOSED TO BE PENNANT–AND WORLD SERIES–WINNERS RIGHT OFF THE BAT |

Most successful baseball skippers will tell you that it takes a few seasons to acclimatize to the nuances of managing, and some never do.

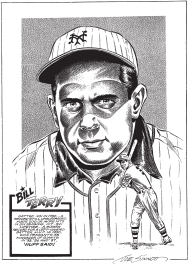

But Bill Terry and Frankie Frisch were incredible exceptions to the rule.

What the pair accomplished in 1933 and 1934 really was one for the books, and a lesson from the proverb nothing ventured, nothing gained.

Their feat was winning both the pennant and the World Series in their first full seasons as managers.

Terry led the New York Giants to the 1933 World Series against the Washington Senators, who were managed by Joe Cronin, himself a first-year manager.

In 1934, Frisch’s St. Louis Cardinals took the crown by defeating the Detroit Tigers, whose manager, Mickey Cochrane, also happened to be a first-year leader.

Other members of the Hall of Fame to win pennants in their first full year of managing were: Tris Speaker, Cleveland Indians, 1920; Rogers Hornsby, St. Louis Cardinals, 1926; and Yogi Berra, New York Yankees, 1964.

Speaker, Hornsby, and Frisch never won another pennant. Cochrane and the Tigers won the pennant in 1935 and went on to defeat the Chicago Cubs in the World Series.

Cronin managed for eleven fruitless years before winning another pennant with the Boston Red Sox in 1946. Berra won the National League Championship in 1973 at the New York Mets’ helm.

|

31 |

A BATTER WHO STRUCK OUT ON ONLY TWO STRIKES |

Ray Chapman was a pretty good ballplayer and not a bad hitter at that. But when it came to facing Walter Johnson, he might as well have been a piece of tissue paper. As for Johnson, his pitching strategy was simple and straightforward.

He relied on his fastball. If it failed to work the first time, he’d throw a faster one the next time. Batters often excuse their strikeouts by explaining, “How can you hit ‘em if you can’t see ‘em?”

One time, Ray Chapman faced the unhittable Johnson. After two swinging strikes, Chapman walked out of the batter’s box and headed for the dugout in disgust.

“Wait a minute,” the umpire called after him, “you’ve got another strike coming.”

“Never mind,” replied Chapman, “I don’t want it.”

|

32 |

ALMOST GIVEN UP FOR DEAD IN WORLD WAR II, LOU BRISSIE RETURNED TO PITCH IN THE MAJORS |

Before the Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, Lou Brissie was playing collegiate baseball and was scouted by the Philadelphia Athletics. The A’s boss, Connie Mack, was impressed with Brissie, but did not want to take him right away. Mack advised Brissie to go to college first and then return to Philadelphia. He added that there would be a uniform waiting for him. Mack even helped Brissie with college expenses to show the young man how serious he was about the boy’s future. Brissie, in turn, was determined to keep Mack’s faith in him and continued playing in college.

A year after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Brissie felt he could no longer put off enlisting. He told his college coach, Coach McNair, of his decision. Coach McNair did not try to dissuade the boy. He knew the boy was strong-willed and his efforts would be in vain.

Two years later, on December 7, 1944, Corporal Brissie and his infantry were in the Appenine Mountains outside of Bologna, Italy. German attackers shelled his platoon. Brissie and his entire outfit were hit. Most of the men were killed, the others critically wounded. Brissie was one of the more fortunate; nevertheless, he was badly wounded. He lay in mud until a search party arrived. To Brissie’s dismay, they appeared to be leaving him there, assuming that all of the men had been killed. Brissie tried to call out to them but could not, due to shock. Then, one of the men in the search party noticed Brissie move. Brissie was given medical attention at a nearby aid station. Forty transfusions later, Brissie was transferred to the evacuation hospital in Naples.

One morning, Brissie awoke to find a doctor leaning over him. The doctor turned to an aide and said, “This leg will have to come off.” Brissie was stunned. He mustered all the strength he could and pleaded with the doctor not to amputate his leg. “I’m a baseball player, and I’ve got to play ball,” Brissie explained. Fortunately for Brissie, the doctor was a baseball fan and understood Brissie’s plight. The boy’s strong will to keep his leg encouraged the doctor to agree that he would do everything he could to save it for him.

Brissie’s leg had been completely shattered. There was scarcely a piece of bone in his leg that was left intact. The doctor did everything he could to put Brissie’s leg back together. Brissie underwent many complicated operations at various hospitals around the country and around the world.

Connie Mack had written Brissie through his years in the army, and after the boy was shot, wrote him more often. Connie assured Lou that there would still be a uniform waiting for him upon his release from the army.

One morning in July 1949, Lou Brissie walked up to Connie Mack’s office on a crutch. Just as Connie had promised, Lou’s uniform was ready for him. Brissie wore the uniform and even warmed up with the bullpen catcher. But the idea that he would ever play Major League Baseball still seemed far-fetched. Brissie underwent major surgery a few days later for an infection in his leg. Most of the Athletics thought they had seen the last of Lou Brissie.

Lou Brissie showed up at spring training in Florida the next year, much to the surprise of the other players. Although not as agile as most, Brissie still managed to play ball. Only one year later, Brissie was pitching for the Philadelphia Athletics. By the end of his career, Brissie had pitched six full seasons of Major League ball.

|

33 |

SIX MANAGERS IN FOUR YEARS—ONLY STEINBRENNER COULD DO IT |

During George Steinbrenner’s reign as the boss of the New York Yankees, the Stadium was dubbed “The Bronx Zoo” for a reason: George ran a managerial merry-go-round, rare in baseball history.

The Boss started making wholesale changes in 1980, when he replaced Billy Martin, on his second tour as manager, with Dick Howser.

Howser was a good choice; he motivated his players (including moody Reggie Jackson) and won the division title. Jackson enjoyed his best season ever: forty-one homers and a .300 average. Jackson’s homers tied for the league lead with Ben Oglivie.

But Howser’s Yankees collapsed in the playoffs, losing in three games straight to the Kansas City Royals. Infuriated, Steinbrenner replaced Howser with Gene Michael, the team’s general manager.

Michael’s cautious managing and deference to George Steinbrenner kept him in first place and in charge when the strike hit in 1981. After the strike, the Yankees were declared the “first-half” winners, assured of a playoff berth. But his over cautious managing in the second half lost games and alienated him from the players. Steinbrenner decided to change managers, bringing in Bob Lemon, who had managed the Yankees’ great World Championship team in 1978.

Lemon stabilized the team and guided it to a victory in the playoffs. But in the World Series, after the Yanks won the first two games, the Dodgers came back to win four in a row. Pitcher George Frazier lost three games for the Yanks in the Series, setting a new World Series record.

Even so, Steinbrenner promised Lemon that he could manage the Yankees all the way through the ’82 season, and Lemon returned to open it. But the Yankees fell apart quickly without Reggie Jackson, who had fled to the Angels after a disastrous 1981 season.

Bereft of effective power and pitching, the Yankees stumbled around until mid-May, when Steinbrenner had seen enough. Out went Lemon; back came Gene Michael.

However, Michael was no improvement. One night, the Yankees lost both ends of a doubleheader to the lowly Cleveland Indians, with Steinbrenner in attendance. The fans directed their wrath at Steinbrenner, and the boss was annoyed. His first move was to allow fans to use their tickets as rain checks for other games.

His second move was to fire Gene Michael and bring in super scout and former pitching coach Clyde King as manager. King restored some order, but the season was too far gone to save.

When all was over, Steinbrenner changed managers again, bringing in his sixth skipper, on his third trip: Billy Martin, the very man he started with at the end of 1979.

Round and round goes the merry-go-round.

|

34 |

THE IMPROBABLE COMEBACK IN THE SUMMER OF 1978 |

The 1978 Yankee season was a story written for Hollywood. The turbulent relationship between Reggie Jackson and manager Billy Martin was a story in itself.

It’s hard to imagine, after winning the World Series in 1977, that the Yankees would repeat without their manager. That’s exactly what happened in 1978.

After Martin learned about Yankees principal owner George Steinbrenner’s plan to fire him, he lashed out to the public. “They deserve each other. One’s a born liar [Reggie Jackson] and the other’s convicted [referring to Steinbrenner’s conviction for making illegal donations to Richard Nixon’s 1972 campaign].”

The next day, on July 24, Martin resigned before George could fire him. The Yankees hired Bob Lemon, who was fired approximately one month earlier by the Chicago White Sox.

The Red Sox were running away with the American League East. Lemon’s team gave New York three months of baseball that you had to see to believe. The Yankees were ten and a half games out of the lead.

Lemon first addressed the team by saying, “So why don’t you just go out and play the way you did last year, and I’ll try to stay the hell out of the way?”

Lemon’s objectives were clear: straighten out the pitching staff and get Jackson to play up to his ability.

The Yankees went on a tear, winning almost every time they played. The Yankees somehow put themselves within striking distance of the Boston Red Sox, with four games left, all against the Red Sox, and all in Fenway Park. This series went on to be known as the Boston Massacre.

After sweeping all four games, the teams played a one-game playoff to determine who would be going to the postseason.

The playoff game had a similar trajectory to that of the season. The Red Sox jumped out to an early lead, and the Yankees battled their way back.

The most unlikely of players became a name that will forever live in infamy. Bucky Dent hit a towering drive over the Green Monster to give the Yankees a 3–2 lead.

The Yankees went on to win the game and the World Series for a second consecutive season.

What many fail to remember is that these two teams battled through perhaps the finest division in baseball history—five teams finished with at least eighty-six wins, four of them with ninety wins or more. That the Yankees passed all of them in their run, and then won on enemy turf with a home run from their choked-up shortstop, all before winning a second straight World Series crown, makes this the cream of the crop in terms of comebacks in the American League.

|

35 |

FROM THIRD-STRING CATCHER TO FIRST-STRING SPY |

Morris (Moe) Berg hardly had a distinguished baseball career. If anything, his only claim to diamond fame was longevity. The catcher from Newark, NJ, lasted in the bigs from 1923 to 1939, playing for the Brooklyn Dodgers, Chicago White Sox, Cleveland Indians, Washington Senators, and finally, the Boston Red Sox.

It was in the realm of spying that Berg was exceptionally successful. Working for Uncle Sam when he wasn’t behind the plate—among other feats—Berg laid the groundwork for General Jimmy Doolittle’s thirty-second bombing of Tokyo in 1942.

In another instance, Berg was responsible for British Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s support of Marshal Josip Broz Tito’s Nazi-resistance group over Commander Dragoljub Mihalovic’s Serbian forces. Parachuting into Yugoslavia at age forty-one, Berg took stock of Marshal Tito’s scrappy partisans and reported back to Churchill.

It was Moe’s impressive status as a polyglot that led him to espionage. His pharmacist father, Bernard, taught him Hebrew and Yiddish, and he learned Latin, Greek, and French in high school. At Princeton University, Berg added Spanish, Italian, German, and Sanskrit to his repertoire, and after studying in Paris and then Columbia Law School, he picked up Hungarian, Portuguese, Arabic, Japanese, Korean, Chinese languages, and more Indian languages. In all, he boasted knowledge of fifteen languages, not to mention the various regional dialects.

Berg began playing baseball at age four, but his stern father disapproved of the ball game and refused to watch his son play, even when Moe played shortstop for Princeton. After college, Berg went on to play for the Brooklyn Robins (later the Dodgers) as a backup catcher. His baseball career was mediocre at best, but he was venerated by sportswriters, fellow players, and fans alike for his intellectual brilliance.

Japanese baseball fans were no exception; they were thrilled when Berg was, somewhat unexpectedly and, in light of his position as a third-string catcher, somewhat undeservedly, chosen to accompany MLB greats, such as Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, on an All-Star tour of Japan in 1934. Yet, unbeknownst to all—save for key U.S. government officials—Berg was not on tour to promote the sport of baseball.

Instead, the Japanese-speaking Princeton grad was instructed to film key features of Tokyo for use in General Doolittle’s 1942 raid.

Berg was also tasked with determining how close the Nazis were to constructing the world’s first atomic bomb. With famed physicist Werner Heisenberg at the forefront of the German nuclear energy project, the stakes were getting higher by the day.

Posing as a Swiss graduate student, Moe Berg sat in the front row of the Nobel Laureate’s lecture with a pistol and a cyanide pill in his pocket. His task: assess the Nazi’s progress on building a nuclear bomb, and if he judged that they were close to achieving their goal, he was to shoot Heisenberg and swallow the cyanide pill. Fortunately for all, Berg’s assessment came back negative.

After the war, Berg found himself out of a job. He occasionally received intelligence assignments, but always saw himself as a ballplayer. When asked, “Why are you wasting your talent?” Berg responded, “I’d rather be a ballplayer than a Justice on the U.S. Supreme Court.”

Moe Berg was awarded the Medal of Merit—America’s highest honor for a civilian in wartime. But Berg refused to accept it, as he could not tell people about his exploits. After his death, his sister accepted the medal, and it hangs in the Baseball Hall of Fame, in Cooperstown, NY.

|

36 |

STAN MUSIAL SHOWS WHY HE IS “THE MAN” |

When Stan Musial’s name comes up for discussion among those who know baseball’s history best, the first of his feats that comes to mind is the man’s seven National League batting championships.

His clutch hitting—especially at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field—inspired Dodger fans to nickname him “the Man.”

More specifically, when Musial walked up to the batter’s box at the Flatbush ballpark, Dodger fans were likely to murmur, “Here comes the man!” A writer covering the Dodgers-Cardinals game one day overheard the comment, and from that point on, Musial was “Stan the Man.”

As effective as Musial was in Brooklyn, his best day as a home run hitter took place on May 2, 1954, at Busch Stadium in St. Louis. On that day, in a doubleheader against the New York Giants, Musial hit five home runs.

Musial had three homers in the Cards’ first fourteen games, and there was little reason to suspect that he would break out in a rash of four-baggers this time, particularly with Johnny Antonelli, one of the league’s top southpaws, pitching the first game for the Giants.

His third and final home run in the first game was a game-winning blow. The Cards won 10–6 behind Stan’s three home run performance.

Manager Leo Durocher of the Giants nominated Don Liddle, another lefty, to work the nightcap. In Musial’s second plate appearance of the second game, he was finally retired: the first time he was sent back to the dugout all day.

Knuckleballer Hoyt Wilhelm was on the mound for the Giants when Musial came to the plate again. With one man on base, Musial connected again, hammering a ball over the pavilion roof for his fourth homer of the day.

Then in the seventh inning, Stan punished another ball over the right field roof. This narrowed the Giants’ lead to one run. The Cards could not get another run across and split the doubleheader.

In eight official trips to the plate, Musial collected five home runs, one single, nine runs batted in, and twenty-one total bases. He set a Major League record with his five homers in the twin bill and tied the record for homers in two consecutive games.

|

37 |

FROM MISTER ANONYMITY TO ALL-TIME HERO |

For most of his baseball career, preceding the 1951 season and right up to the homestretch, Bobby Thomson of the New York Giants hardly could be called a household name in the diamond business.

True, the Jints’ third baseman-outfielder played well, but hardly was a headline-grabber. But that was to change in one of the most curious homestretches in history.

By late summer, the Giants and Brooklyn Dodgers had engaged in a thrilling late-season race for the playoffs. The Giants, who trailed the League-leading Dodgers by thirteen and a half games in mid-August, managed to climb their way back. They won thirty-seven of their final forty-four games and secured the opportunity to play the Dodgers in a three-game playoff for the pennant.

In dramatic fashion, the series came down to a decisive third game. The Dodgers sent twenty-game winner Don Newcombe to the mound to face the Giants in the Polo Grounds. And he produced. Newcombe took a 4–1 lead to the ninth. The righty was dominant for eight innings, but ran out of steam to open the ninth. After giving up a run on three hits and only retiring one batter, Newcombe’s day was done. Enter former twenty-one-game winner Ralph Branca.

Branca was given the task of facing the Giants’ Bobby Thomson with the tying runs on base. Thomson had already done damage—both good and bad—in the series. His go-ahead two-run homer in the first game gave the Giants an early advantage in the playoff. The second game was a much different story. Thomson’s base-running mistakes and errors in the field contributed to a defeat at the hands of the Dodgers. He had a chance to redeem himself against Branca.

After taking a first-pitch strike, Thomson locked in on the second one, a fastball. He pulled it to left field. When the ball entered the stands above the left field wall, the Polo Grounds erupted. Thomson triumphantly circled the bases and was welcomed at home plate by his even happier teammates.

While fewer than thirty-five thousand could say they actually saw “the shot heard ‘round the world,” Russ Hodges illustrated the scene for tens of thousands listening to the radio broadcast, putting them at the Polo Grounds with the spectators. Hodges’ call of “the shot heard ‘round the world” is one of the most memorable in sports history. The image of Thomson rounding the bases isn’t complete without Hodges’ “The Giants win the pennant!” call to accompany it.

|

38 |

THE EVANGELIST WHO DOUBLED AS A BASEBALL STAR |

Religion and baseball often go hand in hand, but in one extreme case, a member of the clergy also happened to be a diamond star.

In his day, Billy Sunday was more renowned as a ballplayer than he was before turning to a career on the pulpit, where his full moniker was Reverend Billy Sunday.

Before that, he was an outstanding outfielder with the Chicago White Stockings. Many observers credited Sunday with helping Chicago win the pennant in 1886. It all happened in a crucial game between Detroit and Chicago, with the White Stockings holding a slim lead over their opponents.

Detroit had two men on base with two out and catcher Charley Bennett at the plate. The pitch was just where Bennett wanted it, and he slammed the ball toward very deep right field. Sunday, who was considered the fastest man in both leagues, turned and ran in the direction of the ball. He leaped over a bench on the lip of the outfield and continued running. As he made his way, Sunday talked out loud: “Oh, God. If you’re going to help me, come on now!” At this point, Sunday leaped in the air and threw up his hand. He nabbed the ball and fell on his back. Thanks to Sunday, Chicago won the game and, eventually, the pennant.

Sunday enjoyed telling friends that he played for two teams, the White Stockings and “God’s team.” When asked how he got on God’s team, Billy would explain: “I walked down a street in Chicago with some ballplayers, and we went into a saloon. It was Sunday afternoon and we got tanked up, and then went and sat down on a curbing. Across the street, a company of men and women were playing on instruments—horns, flutes and slide trombones—and the others were singing the gospel hymns that I used to hear my mother sing back in the log cabin in Iowa and back in the old church where I used to go to Sunday school. I arose and said to the boys, ‘I’m through. I am going to Jesus Christ. We’ve come to the parting of the ways.’”

Although his teammates needled him, Sunday followed the Salvation Army singers into the Pacific Garden Restaurant Mission on Van Buren Street. Billy may not have known it at the time, but he was on his way to the Sawdust Trail where, as he put it, he would emerge as the scrappiest antagonist that “Blazing-eyed, eleven-hoofed, forked-tail old Devil” ever had to go against.

|

39 |

WAS THIS THE ALL-TIME BASEBALL BONEHEAD PLAY? |

A name and expression have become synonymous in baseball lore over the decades.

The ballplayer was Fred Merkle of the New York Giants.

The expression that became so closely synonymous with the first baseman was bonehead.

Until that date, September 23, 1908, Merkle was as anonymous as a National League rookie could be. But that all changed in a game against the Chicago Cubs.

It was a contest that would decide the pennant, and it appeared as if the Giants would take the flag.

After all, they were nestled in first place by six percentage points over Chicago and were playing at home in Harlem.

But that was where the Giants’ good luck ended and Merkle’s bonehead saga reached Chapter One.

With the score tied, 1–1, and two out in the last half of the ninth inning, Moose McCormick of the Giants was on third and Merkle on first.

When Al Bridwell singled to center field and McCormick crossed the plate with what appeared to be the winning run, the jubilant crowd surged onto the field.

But Merkle, seeing McCormick score, had never bothered to continue to second base. Instead, he ran to the clubhouse to escape the onrushing fans.

Meanwhile, Solly Hoffman, the Cubs’ center fielder, threw the ball toward second base, but his throw was wild.

Floyd Kroh, a substitute, attempted to retrieve it, but Joe McGinnity raced over from the Giants’ coaching box, wrestled him for it, and is believed to have thrown it into the stands.

Somehow, the second baseman obtained another ball, stepped on second, and raced over to the plate umpire, Hank O’Day.

The first base umpire, Robert Emslie, had been watching first and missed the play entirely. But when O’Day told him what had happened, Emslie called Merkle out.

O’Day, an umpire in the league as early as 1888, went back to his hotel and after eating dinner, sat down and wrote the following letter to Harry G. Pulliam, president of the National League.

NEW YORK, SEPT. 23/08

HARRY C. PULLIAM, ESQ.

PRES. NAT. LEAGUE

Dear Sir:

In the Game today at New York between New York and Chicago, in the last half of the ninth inning the score was tied 1–1, New York was at the bat, with two men out, McCormick of New York on 3rd base and Merkle of N.Y. on 1st base; Bridwell was at bat and hit a clean single Base-Hit to center field. Merkle did not run the ball out; he started toward second base, but getting half way there he turned and ran down the field toward the clubhouse. The ball was fielded in to second base for a Chicago man to make the play, when McGinnity ran from the coacher’s box out in the field to second base and interfered with the play being made. Emslie, who said he did not watch Merkle, asked if Merkle touched second base. I said he did not. Then Emslie called Merkle out, and I would not allow McCormick’s run to score. The game at the end of the ninth inning was 1–1. The people ran out on the field. I did not ask to have the field cleared, as it was too dark to continue play.

Yours Respectfully,

Henry O’Day

To understand properly the meaning of the Merkle play and to determine whether O’Day and Emslie made a good decision, some background is necessary.

The rules, of course, are quite clear that when the third out of an inning is a force-out, no runs can score on the play. The trouble was, the rule had never been enforced.

Less than three weeks earlier, on September 4, in a game between Pittsburgh and Chicago, a Pirate runner, Warren Gill, did exactly what Merkle did.

O’Day was umpiring the game and refused to call Gill out. He couldn’t confer with anyone, as he was umpiring the game alone.

But after thinking about it, O’Day determined that if the play ever happened again, he would call the runner out.

So there never would have been a Merkle story if O’Day had not been the umpire behind the plate, or if the play on Gill had not come up, or if the same man, Bud Evers, had not been playing second base.

It was an unusual and coincidental set of circumstances.

Bill Klem, one of the best known of all Major League umpires, always insisted that the decision on Merkle was the worst in the history of baseball.

Klem’s thinking was that the rule in question was intended to apply only to infield grounders and not to safe hits. However, O’Day interpreted the rule as written.

Both the Giants and the Cubs protested the decision of the umpires to replay the “tied” game. The Giants claimed that they had legitimately won the game, 2–1.

The Cubs maintained that they should be awarded the game by forfeit, first because of McGinnity’s interference, and then because the Giants had refused to play the game the following day, as required by league rules.

Despite Pulliam’s decision to side with the umpires, the two teams continued their protest to the league’s board of directors, which ordered the game replayed on October 8.

The Giants and Cubs were tied for first place on the day of the replayed game, each with 98–55 records. The Cubs defeated the Giants, 4–2, and annexed the championship.

In failing to touch second base, Merkle only did what many players had already done, yet he was called every epithet printable, and some that weren’t.

The Sporting Life, a baseball publication, noted that “through the inexcusable stupidity of Merkle, a substitute, the Giants had a sure victory turned into a doubtful one, a game was played in dispute, a complicated and disagreeable controversy was started, and perhaps the championship imperilled or lost.”

Apparently, the only prominent sportswriter to take a sensible view of the affair was Paul W. Eaton, a freelance writer in Washington, D.C.

“A protest may well be recorded against the many severe criticisms of Merkle that have been made,” Eaton wrote.

“His accusers seem to have agreed on the epithet of ‘bonehead.’ It can be stated most emphatically that in failing to touch second after Bridwell’s hit, Merkle did only what had been done in hundreds of championship games in the Major Leagues.”

Merkle, understandably heartbroken, returned to his parents’ home in Toledo, Ohio. Reporters crowded around him there, swarming like bees.

Merkle then told a side of the story that had eluded everyone–that his hit that sent McCormick to third might easily have been for extra bases.

“The single that set up the play might have been a double or a triple,” he explained. “But Jack Hayden, the Cub right fielder, made a wonderful stab and knocked down the drive. At that, I could have gone to second easily, but with one run needed to win and a man on third, I played it safe. When Bridwell got the single that should have won the game, I was so happy over the victory, I started for the clubhouse, figuring, of course, on getting out of the way before the crowd blocked the field. When I heard Evers calling for the ball, and noticed the excitement, I did not know at first what it was about, but the meaning of it all suddenly dawned on me and I wished that a large, roomy, and comfortable hole would open up and swallow me. But it is all over now and will have to be forgotten.”

But seven years later, the play was not forgotten. At that time, a writer asked Merkle, “Do you get any fun out of baseball?”

“No,” Merkle replied, “I wouldn’t call it fun. I have too rough a time out there.”

“Do the fans still ride you?”

“Yes. The worst thing is, I can’t do things other players do without attracting attention. Little slips that would be excused in other players are burned into me by the crowds. Of course, I have made mistakes with the rest, but I have to do double duty. If any play I’m concerned with goes wrong, I’m the fellow who gets the blame, no matter where the thing went off the line. I try not to mind it too much; I’ve been ridden enough to get used to it, but nobody’s as thick-skinned, but what a roast will get under his skin at some time or another.”

The Merkle play was such a “touching” story that the following year a book called Touching Second? was dedicated to the second baseman, Evers, by Hughie Fullerton.

Surprisingly, there is reason to believe that Merkle did touch second. But not exactly right after the incident.

Tom Meany, a baseball authority and author, once learned after the game that Merkle’s manager had seen to it that Merkle was secluded in the Shelbourne Hotel in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, and that in the middle of the night he had the boy return to the Polo Grounds and touch second, so that if he were ever asked under oath, he could swear that on September 23, 1908, he had second!

|

40 |

BARNEY KREMENKO’S MISTAKEN SIGNALS |

During the late 1940s and early 1950s, Barney Kremenko covered the New York Giants for the Journal, Hearst’s flagship afternoon daily in New York City.

As sports journalists go, Kremenko was passionate in the extreme. He loved the Giants and was especially close to manager Leo Durocher, a firebrand bench boss if ever there was one.

When in a pinch, Durocher knew that he could count on Kremenko, and vice versa.

This point was proven beyond a shadow of a doubt during the 1951 pennant race between the Giants and Brooklyn Dodgers.

During the second inning of a critical game at the Polo Grounds, Leo was coaching at third base when his slugging center fielder, Willie Mays, attempted to stretch a double into a triple.

Although Mays was under the tag and appeared to be safe, the umpire loudly called him “out!”

Furious with the call, Durocher argued with the arbiter and then made the mistake of kicking dirt on the umpire’s trousers.

The ump wasted no time tossing Durocher out of the game, which caused a minor crisis with Giants strategy.

Since the Lip masterminded most of the Giants’ moves, he decided on a plan whereby he could continue coaching–from the press box.

Cornering Kremenko, Durocher whispered that he’d stand behind Barney for the rest of the game. From time to time, Leo advised, he’d give his favorite writer a signal to flash down to his replacement third base coach.

Tickled to be a temporary part of the Giants’ general staff, Kremenko agreed to the plan, and for several innings it worked to perfection.

Then in the eighth inning, the scheme went up in smoke.

The problem started when catcher Wes Westrum singled to center with what would have been the tying run.

Notoriously slow-footed, Westrum never was a threat to steal a base nor was he expected to do so on this fine day.

But strange things were happening, starting with Kremenko as quasi-coach.

After Westrum delivered this single, Barney began writing his “running” account of the game for the Journal–American's late edition.

Perspiring in the August heat, in an ancient press box with no air-conditioning, the avid writer stopped typing for a moment.

Then a pause, and with his right hand, Kremenko wiped the sweat off his brow.

Just two seconds later, Westrum suddenly broke for second base in what appeared to be a brazen attempt to catch the Dodgers off guard.

But that did not happen and catcher Roy Campanella flied a perfect strike to second baseman Jackie Robinson, who had Westrum out by a country mile.

The astonished spectators, wondering why Westrum dared to steal, couldn’t have known what had transpired, but Durocher did.

Slapping Kremenko gently on the back at the writer’s desk, Leo blurted, “WHEN YOU WIPED THE SWEAT OFF YOUR BROW, YOU FOOL, YOU GAVE THE HIT AND RUN SIGN!”

|

41 |

INCREDIBLE FEATS BY BASEBALL PLAYERS IN WORLD WAR II |

One of the best players of all before the war was Cecil Travis of the Washington Senators. A combatant during the hellish Battle of the Bulge (Belgium, 1944–45), Travis came out of the assault with badly frozen feet. When he returned to the Senators at the conclusion of the war, he was unable to regain his prewar abilities.

Another former Senators player, Elmer Gedeon, died in action, as did Harry O’Neill, who played but one game for the Philadelphia Athletics. Ironically, Billy Southworth Jr., son of the St. Louis Cardinals manager, survived twenty-five bombing missions over Europe, but died trying to make an emergency landing at LaGuardia Field in Queens, New York, in February 1945.

Among other prospects who suffered as a result of the war was Johnny Grodzicki of the St. Louis Cardinals, who was considered a potential twenty-game winner. Because of a wound, Grodzicki was unable to use his right leg effectively and was only a shade of his former prewar self. Likewise, Cardinal infielder Frank “Creepy” Crespi lost his chance at a postwar career because of a pair of weird mishaps. First, Crespi broke his leg during an army baseball game. Then, while recovering, he participated in a wheelchair race at his hospital and rebroke the leg.

Few suffered as terribly as Philadelphia Athletics’ pitcher Lou Brissie, a soldier in the Italian campaign. Wounded by shell fragments, Brissie was hospitalized with two broken feet, a crushed left ankle, and a broken left leg, as well as injuries to his hands and shoulders. Brissie not only recovered from his wounds but even joined the Athletics after the war, and developed into a first-rate pitcher.

Still another hero was pitcher Phil Marchildon of the Athletics, an airman whose plane was shot down by the Nazis. Taken to a prisoner-of-war camp, Marchildon lost thirty pounds over a period of a year, but survived. When he returned to the United States, his physical condition was so precarious that many doubted he would pitch again. However, the Athletics’ manager Connie Mack persuaded Marchildon into putting on a uniform for Phil Marchildon Night. More than thirty thousand Philadelphians turned out to cheer Phil, who responded by pitching three innings. A year later, he was pitching like the Marchildon of old, winning thirteen and losing sixteen for the Athletics. His best season was 1947, when he went 19–9.

|

42 |

FROM HOCKEY GOALIE TO BASEBALL MANAGER |

When semipro baseball was a big deal throughout Western Canada in the 1940s, Emile Francis managed some of the best Canadian teams. But during the winter, Francis’ night job was as a goaltender.

Francis, who played goalie for the Chicago Blackhawks and New York Rangers, also was an accomplished shortstop.

One of his more power-packed teams was the North Battleford (Saskatchewan) Beavers from Francis’ hometown. It was a club loaded with black players, many of whom made their way to the American and National Leagues.

“We played in the old Western Canada League,” Francis recalls. “Later its name was changed to the Canadian-American League. In any case, we had some of the best players on the continent. One year, no less than twenty-six were signed out of our league in to the majors.”

Such accomplished Major Leaguers as Don Buford, Ron Fairly, and Tom Haller played for and against Francis, not to mention a number of superb college stars. “They couldn’t play professional ball in the States,” Francis remembers, “so they’d come up to Canada, get paid, and get good experience. Nobody snitched on them either.”

A spunky hockey player, Francis was no less pugnacious on the diamond. He was involved in a number of bristling episodes, including one game that erupted into a full-scale riot. It took place in Rosetown, Saskatchewan, during a tournament involving teams from the United States and Cuba.

“We were playing this team—the Indian Head Cubans—and the stakes were high,” says Francis. “It was something like $2,000 per man and nobody wanted to lose.

“Well on this one play, one of our players slid hard into second and upset the Cuban shortstop. Next thing we know, the whole bunch of the Cubans ran off the field and I was damned if I could figure out what they were up to; but it didn’t take long for me to understand. They had gone to the bat rack and they were coming back at us with bats.

“The battle that followed took an hour and a half to cool down, but that wasn’t the half of it. Two of the Cubans took off after one of our players. I could see them chase him out to the parking lot, and I followed as they went down a dirt road, heading for a farmer’s house. My player was still in the lead and he made it to this farmhouse. He ran in, grabbed a butcher knife from the kitchen, and came right out at the Cubans. They were all about to go at it . . . when just in time the Royal Canadian Mounted Police arrived and broke it up.”

++2a01By the time the dust had cleared, the game resumed and Francis’ team won. He got his knife-wielding player out of jail and headed for Moose Jaw for another game.

This time, the knife-wielder came up with a perfect night, five hits in five times at bat.

“After the game,” says Francis, “I got a wire from the local sports editor. He wrote: ‘OUT OF THE FIVE HITS YOUR MAN GOT, HOW MANY CUBANS WERE SENT TO THE HOSPITAL?’”

Francis also teamed up on the baseball field with Hockey Hall of Famers Max and Doug Bentley of Delisle, Saskatchewan, as well as other Bentley brothers. “At one time I was surrounded by Bentleys. There were five altogether on my teams. One day, a fan shouted at me: ‘Francis, there’s only one way you could’ve made this team; you must have married a Bentley.’”

|

43 |

THE DAZZY WHO GOT THEM DIZZY |

Among the long list of pitchers who combined skill with humor, Dizzy Dean ranks among the very best.

Dizzy was so adept at what he did, that his accomplishments often obscured those of another mound stalwart whose named sounds a lot like Dizzy’s.

That would be none other than Dazzy Vance, who—in one compelling way—could top Dean when it comes to an incredible feat.

As it happened, Dazzy didn’t get Major League batters dizzy until he reached the ripe, old baseball age of thirty-one.

Vance had problems with his right arm from the inception of his career. He was never really sure what was wrong with it, either. Dazzy was sent to the minors for the 1916 season. For the next five years, his pitching record suffered because of that sore arm. Sometimes his arm hurt so badly that he didn’t want to pitch, and he hardly could. He had no alternatives to playing baseball; it was the only thing he knew how to do, and he had to support his family somehow.

For a time, he soaked his arm in ice water. After a while, though, even that remedy didn’t work. A doctor told Vance that if he laid off pitching for four or five years, it would probably stop bothering him. Dazzy’s response to the doctor was “and how am I going to eat in the meantime?”

Vance was supposed to play for the Toledo, Ohio, team in the 1917 season. During spring training, he looked terrific. As soon as the season started, he tired easily and was soon being whipped by the opposition. Vance moved to Memphis, but the same fate awaited him there. At first, he’d shut out the batters with his fastball, and then he’d get worn out and have to leave the game. He pitched two games for the Yanks in 1918 and then returned to the minors. Spencer Abbott, manager of the Memphis team, traded Vance to New Orleans. He had no time or patience for someone who couldn’t perform.

After about two weeks in New Orleans, Vance’s arm began to feel better, and his pitching picked up. The following season with New Orleans, he won twenty-one games. By chance, his performance attracted the attention of the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Hank DeBerry was a New Orleans catcher who was being noticed by the Major Leagues. Larry Sutton, the Dodgers’ top scout, was sent out to look at DeBerry, since the Dodgers needed a catcher badly. Sutton returned to Wilbert Robinson, manager of the Brooklyn team, to report that they should take both DeBerry and Vance.

Vance was not yet thirty-one years old, had played with a dozen different teams, and was well known for his sore arm. Nevertheless, Dazzy became a Dodger. One night in a spring exhibition game against the St. Louis Browns, Vance was pitching and faced George Sisler, one of the greatest hitters of all-time. Vance threw the first pitch, a strike. The second pitch was a strike too. With two strikes on Sisler, Vance wound up and sent a curve ball flying toward the plate. Sisler knew he was out.

Robinson was ecstatic. He hadn’t known what a good buy he had found. “Anyone who can catch Sisler looking at a curve must be throwing a pretty good one,” commented the Dodger manager.

From that point on, Vance was a first-rate player. In his first full season, he won eighteen games and led the league in strikeouts. His second season was a duplicate of the first. His third season was better–twenty-eight wins and only six losses. He was voted MVP.

No other pitcher has done what Vance did–he led the league in strikeouts for seven years in a row! Upon his retirement, Dazzy had won 197 games and struck out 2,045 batters. Vance was forty-five before he gave up the game. In 1954, he was voted into the Hall of Fame.

|

44 |

THE REDHEAD WHO TURNED BASEBALL BROADCASTING INTO AN ART FORM |

One of the neatest aspects of baseball as an entertainment vehicle has been the fact that the sport, over the decades, has been graced by Grade A announcers–both on radio and television.

The likes of Vin Scully, Mel Allen, Bill Mazer, and Ernie Harwell are just a few who became favorites because of their professionalism and unique style.

But the pioneer of them all was a Southerner who came to fame originally in the 1930s, handling the microphone for the Cincinnati Reds.

Red Barber not only was the voice of the Reds, but also the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Yankees.

Barber, a Floridian by birth, emerged as the dean of baseball broadcasters on the basis of his pioneering work in the field, as well as the quality of his broadcasts, timbre of his voice, and basic objectivity; not to mention his penchant for innovation.

After working for a Cincinnati radio station, Barber became baseball’s first play-by-play broadcaster. When Larry MacPhail, the Reds’ general manager who fathered the idea of broadcasting the ball games, moved to Brooklyn where he ran the Dodgers, he took Barber with him.

As the “Verse of the Dodgers,” Barber became a legend in his time, and so did his original phrases. Red’s broadcast booth became known as the “catbird seat.” When the Dodgers filled the bases, Red described the situation as “F.O.B.” (full of Brooklyns). A spectacular play elicited a gushing “Oh! Doctor!” And when manager Leo “The Lip” Durocher became embroiled with umpire George Magurkirth, “the Ole Redhead” described the fracas as “a rhubarb.” (Hollywood, seizing on Barber’s line, later filmed a Brooklyn baseball movie called Rhubarb, about a cat who wanted to play for the Dodgers.)

Barber, who was behind the microphone for the 1949 Dodgers-Yankees World Series, was the first to handle the baseball telecast and also introduced the “pregame show” to the air. Red went into the Dodgers’ dugout with a microphone before the season opener between the Dodgers and Giants. For the first time, thanks to Barber, listeners actually could hear the ballplayers’ own voices.

Before the era when broadcasters traveled with the teams, Barber would recreate the Dodgers’ “away” games from telegraph reports, which continuously poured into the studio over a Teletype machine. Occasionally, the wire would “go out,” but Barber never would resort to tactics employed by other broadcasters who would simply waste time by faking action (“Jones has fouled off thirty-seven pitches in a row”). Barber explained: “I assumed my listeners knew that it was a wire recreation. I even used to have the telegraph machine close at hand, so it could be heard over the microphone. When the wire ‘went out’ I used to tell my listeners, ‘I’m sorry, but the wire has gone out east of Pittsburgh.’”

Barber’s influence was felt by all of those with whom he worked. One of the most accomplished—but unheralded—broadcasters was Connie Desmond, who groomed Vin Scully. Scully has since been the voice of the Dodgers in Los Angeles and one of the best contemporary broadcasters.

|

45 |

A BASEBALL PUBLISHER WHO AFFECTED MORE FANS AND SERVICEMEN THAN ANYONE IN THE LITERARY BUSINESS |

For more than a century, the weekly publication called The Sporting News was regarded as the bible of baseball.

Its publisher, J. G. Taylor Spink, often seemed more powerful than the commissioner himself, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis. If there were such a thing as a king of baseball journalism, Spink was that man.

To those who knew him well, Spink was both amusing and terrifying. He had a habit of waking his correspondents—working newspapermen in the big cities—at all hours of the night. Some loathed him for that, but others loved him. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt wrote Spink a fan letter during World War II. The high commands of the army, navy, and air force saluted him for getting four hundred thousand copies of The Sporting News to servicemen every week during the war. At a testimonial dinner for Spink in 1960, the Athletic Goods Manufacturers Association honored Spink with a Revere bowl as “America’s Foremost Sports Publisher.”

Colleagues remember Spink for his eccentricities. He was obsessive about punctuality and hard work. Once, a member of the staff was two hours late at the office, whereupon Spink demanded an explanation. “I was kept awake all night by a toothache,” said the writer, holding his jaw. To which Spink snapped: “If you couldn’t sleep, there was no reason for you to be late this morning.”

According to Gerald Holland of Sports Illustrated, Spink probably fired most of the correspondents who worked for him. In most cases, however, the staff members returned. “When Spink’s temper cooled,” said Holland, “Spink usually told them a humorous story, by way of indirect apology, and frequently gave them a raise or a gift to assure them that all was forgiven.”

When Spink died in 1962, one of the first to arrive at the publisher’s funeral was Dan Daniel, the New York correspondent for The Sporting News. When someone asked Daniel why he had arrived so early, the reporter replied: “If I hadn’t, Spink would have fired me for the forty-first time.”

Before the invention of radar, Spink had a knack for detecting his distant correspondents and cartoonists (such as award-winning Willard Mullin of the New York World-Telegram) wherever they might be hiding. “Spink,” said Mullin, “could get you on the pipe from any place, to any place, at any time.”

Once, Mullin was invited by a friend to play golf on a course that he had never seen before. “All was well,” Mullin recalled, “until, as we were putting on the sixth green, a messenger came galloping from the clubhouse, tongue hanging out, with the message from Garcia [Spink]. I don’t know how the hell he found me, but it was him!”

On another occasion, Spink pulled the telephone off his office wall during negotiations to move the Braves from Boston to Milwaukee. The publisher had been calling Lou Perini, one of the principals in the deal, night and day in an attempt to get the scoop. He eventually got the scoop, at the expense of his phone and the wall. After several dozen calls, he phoned Perini one morning and said: “Hello, Lou. This is Taylor.”

Then, responding to the inquiry from Perini, said, “Whaddya mean, Taylor who? TAYLOR SPINK.”

Then, another pause to consider the question from the other end. “SPINK–S-P-I-N-K, you sonofabitch.”

At which point, the phone was ripped off the wall.

Carl Benkert, a former executive for the baseball bat company Hillerich and Bradsby, attended the Kentucky Derby with Spink. “Throughout the preliminary races,” said Benkert, “Spink checked the racing form and yelled at people countless times, asking opinions about which horse would win. He even went to the window to buy his own tickets.”

Finally, the race began and several companions wondered which horse the publisher eventually selected. When Middleground crossed the finish line first, Spink leaped for joy. “I had him! I had $100 on his nose!”

The publisher’s companions were suitably impressed until Spink’s wife, Blanche, turned to her husband and then her friend. “I have news for you. He also had $100 on each of the other thirteen horses in the race!”

Spink either didn’t remember or didn’t see every one of his correspondents. During a trip to New York in the 1940s, he was heading for Ebbets Field in Brooklyn where he noticed that the taxi driver’s license read “Thomas Holmes.” Spink was curious. “Are you Tommy Holmes, the baseball writer? The one who works for the Brooklyn Eagle?”

The cabby’s voice turned somewhat surly. “I am not,” he replied to Spink. “But some crazy sonofabitch out in St. Louis thinks I am, and keeps telephoning at three o’clock in the morning!”

Red Barber, the beloved radio announcer, found a soft spot in the publisher’s heart when he visited Spink’s office and noticed an out-of-print book on the shelf. Spink gave it to Barber, and the broadcaster immediately offered to pay for the prize antique. Spink refused. “What could I do for you?” asked Barber.

A smile crossed Spink’s face. “Be my friend,” he said.

|

46 |

THE MOST INCREDIBLE BASEBALL NICKNAME COLLECTION |

Of all the major sports, baseball takes the lead when it comes to nicknames—otherwise known as monikers or handles.

From the most famous, such as Babe Ruth, the “Sultan of Swat,” to the least known, such as Emil Bildilli, whose nickname was Hillbilly Bildilli.

In between Ruth and Bildilli there have been literally thousands of nicknames-monikers-handles.

However, only three gentlemen—Chuck Wielgus, Alexander Wolff, and Steve Rushin—have actually cataloged these mostly amusing, unreal names.

Wielgus, Wolff, and Rushin actually put their collection between the covers of a book, and for a total of 192 pages have everything from Marty (Octopus) Marion to Bill (Doggie) Dawly.

Their nickname encyclopedia is called From A-Train to Yogi: The Fan’s Book of Sports Nicknames.

Although other sports are mentioned, baseball is dominant.

Here’s one of my favorites—with the authors’ explanation.

John (The Count) Montefusco—Because of his name’s resemblance to the title of Alexandre Dumas’s novel, The Count of Monte Cristo. Edmonton Dantes, the fictional Count, pitched battles, while Montefusco pitched batting practice, but the difference didn’t seem to matter until Montefusco moved to New York, where the media had other nickname notions. Inasmuch as the Yankees had acquired him to solve their right-handed pitching woes, Montefusco was heralded as the “Great Right Hope.”