|

59 |

A REMARKABLE PUN THAT ONLY FRENCHY COULD UTTER |

Well before Yogi Berra signed on with the Yankees, the funniest player in the majors wore a Brooklyn Dodgers uniform. Stanley (Frenchy) Bordagaray was purchased by the Bums in (1942) because the Flatbush nine needed a pinch-runner and utility outfielder-infielder. During his stint in the Pacific Coast League, Frenchy—he was really Hungarian but sported a French-type pencil moustache—was notorious for his speed on the base paths.

Once with Brooklyn, Bordagaray tried to show off his Mercury-like moves whenever possible, and on this occasion he was placed on first as a pinch-runner. Sensing he had a chance to steal second, Frenchy tore up the base path and appeared to have slid safely under the tag.

There was only one problem; umpire George Magerkurth disagreed and called “Out!”

Furious with the decision, Bordagaray leaped to his feet and began assailing the umpire with invective not yet invented and in the process accidentally spat on Magerkurth’s neat, clean umpire’s jacket.

Noting the unwanted spittle, Magerkurth promptly gave an emphatic heave-ho to the Dodger, who had no choice but to head for the clubhouse. But that was only the beginning of Frenchy’s woes. He was immediately socked with a $50 fine and suspended for two games, harsh punishment for a part-time player.

When the fine and suspension were announced the next day, several reporters confronted Bordagaray at his dressing room locker to obtain his view of the self-inflicted mess.

“So, Frenchy,” one of the scribes inquired, “how do you feel about getting thrown out of the game and then being suspended for a pair, and also fined fifty bucks for accidentally spitting on Magerkurth?”

Bordagaray pondered the query for a moment and succinctly replied with incredible logic: “That was more than I expectorated.”

Frenchy-watchers insist that that was the best play—on words—of Bordagaray’s career.

|

60 |

AN INCREDIBLY CORNY CONVICTION |

It’s hard to believe that a baseball manager could get thrown out of a game because of popcorn, but it did happen once. In this case the culprit was an early baseball clown—but also a darn good player and later coach—named Germany Schaefer.

One day, when his team was playing a less talented club, Schaefer showed up in the coach’s box with an oversized bag of popcorn and then proceeded to pay more attention to the confection than the game. Not only would Germany eat the popcorn, but sometimes he’d “feed” it to imaginary birds and squirrels, not to mention his friends in the grandstands.

Not surprisingly, Schaefer’s shenanigans amused everyone but the opposition and the umpires. Enemy pitchers complained that the popcorn machinations distracted their concentration and demanded an end to on-field popcorn.

“Germany’s routine ended during a game against the White Sox,” wrote baseball author Dan Morgan. “While nibbling on Cracker Jacks this time, the umpire sent Schaefer to the showers.”

But before heading for the clubhouse, Germany asked the umpire why he was being given the heave-ho.

“Because,” the umpire concluded, “you’re committing an act contrary to the best interests of the game.”

On-field popcorn has never been a deterrent to pitchers since then.

|

61 |

HOW YOGI BECAME A STAND-UP COMIC |

Yogi Berra is in the Baseball Hall of Fame because of his catching prowess and ability to hit virtually any kind of pitch, anytime, anywhere. Yet, for all Berra’s accomplishments behind the plate for the Yankees and as a World Series hero, the St. Louis native is notorious for his famed stand-up lines such as “It ain’t over ‘til it’s over.”

But what was the very first Yogi-ism that began an endless string of precious punch lines?

It all began in the catcher’s rookie year when Yankees manager Bucky Harris desperately tried to halt Berra’s annoying habit of swinging at bad balls.

“When you get to the plate,” urged Harris, “do me a favor and think just a little. Think of the fact that you’ve got three strikes to pick from the kind of pitch you want. Think of the kind of ball you’re likely to get when the pitcher is behind and when he’s ahead. Just do a little thinking with your swinging, and you’ll be all right.”

Armed with those words of wisdom, Yogi strode to the plate and proceeded to take three straight strikes. Not once did the bat leave his shoulders.

After returning to the dugout, Berra was met by his irate manager. Naturally, Harris wanted an explanation which, of course, Yogi had.

“How come you took three strikes without so much as a half-swing?” Bucky demanded.

“Aw nuts,” Berra shot back, “how kin ya think an’ swing at the same time!”

And, if you’re wondering how Lawrence Berra got the nickname Yogi, it dates back to his teenaged years growing up in the Hill section of St. Louis. When he was a squat fifteen-year-old, his pals thought he looked like a squatting yogi who had been featured in a recent movie. Before that, his family had nicknamed him “Lawdy.” With his nickname in mind, Berra once opined, “If I walked down the street and somebody yelled, ‘Hey, Larry,’ I know that I wouldn’t turn around.”

(Postscript: Although he never went to college, for years Yogi has been the headman at a New Jersey museum, of all things. What could be more incredible than a Yogi Berra Museum that sits on the campus of Montclair State University in Little Falls, New Jersey? The museum also has a “Learning Center,” and if you’ve heard some of his Yogi-isms, you would agree that having his own museum learning center is quite an incredible feat in and of itself.)

|

62 |

HOW TO SQUELCH AN UMPIRE—AND GET AWAY WITH IT |

Over the decades Major League umpires have been notoriously sensitive about the profession and proficiency at handling it. Those who insult the arbiters do so at their own risk and often pay a heavy price (see French Bordagaray). But one individual who miraculously escaped punishment after squelching an umpire was Nick Altrock, former pitcher, coach, and among the all-time funnymen among umpire-baiters.

He proved this point while at bat one day. Nick poled a fastball into the left field stands that just happened to bean a female spectator. While the lady was keeling over in her seat, the umpire shouted, “Foul ball!” He then turned to Altrock and blurted, “I sure hope that woman was not badly hurt ‘cause she sure was knocked out cold.”

After listening attentively, Nick deadpanned his reply: “Knocked out? Not at all. She just heard you call that one right—and fainted from shock!”

|

63 |

THE GREATEST SEASON BY A MODERN-DAY PITCHER [PEDRO MARTINEZ] |

There’s an expression: “genius will out,” which snuggly fits righty Pedro Martinez.

The native of the Dominican Republic experienced a season that could only be described as Special Deluxe.

The year was 2000, in the height of the steroid era when batters were hitting home runs as easily as they exhaled. Martinez finished 18–6 with a 1.74 ERA, four shutouts, 283 K’s (11.8 per inning), and a miniscule .737 WHIP—in the process leading the league in the latter four categories.

But simply saying Martinez “led the league” doesn’t even begin to tell half the story—he didn’t just lead the league, but also he put every other pitcher in baseball to shame.

Martinez’s 1.74 ERA in 2000—a phenomenal accomplishment even in a normal year—was almost a full point better than the next-best starter (Kevin Brown’s 2.58 mark), more than twice as good as Roger Clemens’ 3.70 (the next best in the home run-crazy American League), and a full three points better than the league average of 4.77.

To put that in perspective, Bob Gibson’s 1.12 ERA in 1968 only led the league by just under half a point and was about two points better than the league average. Martinez’s .737 WHIP didn’t just lead the league, but also it’s the lowest mark in the history of baseball—dead-ball era, live-ball era, steroid era—doesn’t matter.

In the entire history of baseball, Pedro allowed just 5.3 hits per nine innings in 2000—1.5 better than the next-best pitcher. His strikeout-to-walk ratio was a joke: 8.875, which was more than 3.5 K’s better than the next-best in the league, and the fourth-best ratio ever recorded by a pitcher in the live-ball era. I could go on and on, but doing so would be like beating a dead horse—Pedro Martinez was head and shoulders better than every other pitcher in baseball’s millennial season.

The numbers Martinez complied in 2000 are phenomenally impressive—even record-setting in some cases—in any era, but to do it at the height of the steroid era is what truly makes it special. If 1968 was the year of the pitcher, then 2000 was the year all pitchers would like to forget. 5.14 runs were scored per game in 2000—the highest mark since 1936—and overgrown sluggers turned games into venerable home run derbies, as a historic all-time high of 1.17 home runs were launched into orbit per game. Combine that with a league slash line of .270/.345/.437, and suddenly the league ERA of 4.77—the second-worst of the live-ball era—makes sense.

If you took the mound in 2000, best bring a bib–because things were likely to get messy. In comparison, when Gibson flummoxed hitters in ’68, the league hit just .237—lowest in history, scored 3.42 runs per game—lowest in the live-ball era, and the league ERA of 2.98 was far and away the lowest of the live-ball era. Pedro Martinez was pitching with grenades in 2000, but he miraculously kept hitters from pulling the pin.

|

64 |

THE MOST SENSATIONAL GAME EVER PITCHED [SANDY KOUFAX] |

In the history of professional baseball (that’s well over one hundred thousand games, but who’s counting?), only twenty-three perfect games have been tossed. One is thrown roughly every 4,400 starts—give or take a couple hundred.

If you’re a fan of percentages, that means every time you watch a baseball game, you have about .023 percent chance of seeing a perfecto—the expression “one-in-a-million” quite literally applies here.

While a perfect game is rare enough, on June 9, 1965, Sandy Koufax and Bob Hendley of the Cubs hooked up for a pitchers’ duel, the likes of which had never been seen before, and hasn’t been seen since a 1–0 victory for Koufax’s Dodgers in which two men—no really, just two—reached base (Lou Johnson, on two walks), a record for futility that still stands today.

Koufax’s exploits alone would be enough to qualify this game as amongst the best ever pitched. The splendid southpaw turned in the most dominating performance of a career full of them, striking out fourteen—including the final six—as he spun his first and only perfect game.

The fourteen K’s was a record for a perfect game that has since been tied by Matt Cain, but unlike Koufax, Cain can’t say he struck out Hall of Famer Ernie Banks three times when he took his turn at making history—or had to find a way to retire another Hall of Fame Cubbie, Ron Santo.

Koufax’s perfecto is also remarkable for one other reason—a lack of a memorable defensive play. It seems like in every perfect game or no-hitter, there’s at least one close call—it could be early, it could be late—but there’s always at least one play where the man on the mound needs some help from his friends. Not so with Koufax. Scour as many accounts of the game as you want, but there’s nary a description of a single hard-hit ball of off Koufax on that fateful day.

Despite Koufax’s phenomenal exploits, it takes two to tango. For a game to truly be the greatest ever pitched, the man toeing the rubber for the opposing side needs to be up for the challenge as well—and all Bob Hendley did was turn in the performance of a lifetime. Hendley surrendered just one run—it was unearned, scored on a throwing error by his catcher—one hit, and two base runners all game long. In fact, Hendley carried a no-no of his own into the seventh, and only lost it on what is described in all accounts as a bloop double by Lou Johnson, who, remarkably, was the only player to reach base for either side that game (he did so twice).

There has never, in the history of baseball, been a double no-hitter, but in September ’65, Koufax and Hendley came as close as anyone ever has and turned in a pair of performances that stand the test of time.

|

65 |

YOU’RE NEVER TOO OLD TO BAT .388 [TED WILLIAMS, AGE 38] |

Perhaps it’s a measure of just how great the man was, but somehow, Ted Williams’ miraculous 1957 season seems to slip through the cracks when discussing the Splendid Splitter’s accomplishments. To explain how astonishing it was for Williams to hit .388 at thirty-eight, first we must examine just how rare it is to hit for such a high average to begin with.

The last man to hit .400 was, appropriately enough, none other than Williams himself in 1941. Since then, only four times has a player hit .380 or above: Williams’ .388 in 1957, Rod Carew’s .388 in 1977, George Brett’s .390 in 1980, and Tony Gwynn’s .394 in 1994 (a strike-shortened season). To put this in perspective, in the same time period, we’ve seen the sixty-home run barrier—once the benchmark of all virtually unattainable statistical goals—shattered seven times, the 100-steal mark equaled or bested on eight occasions, and 150 RBI met or surpassed twelve more times. The point is, players just do not hit .388 anymore—let alone when they’re thirty-eight.

It’s not a stretch to say that by the age of thirty-eight, most athletes—even the great ones—are, to put it generously, on their way out. This much is true, regardless of position or sport. Father Time is the one adversary that remains undefeated—and it’s this fact that makes Ted Williams’ 1957 truly one for the books (literally, in this case).

Let’s take a look, for the sake of comparison, at what some of baseball’s other historically feared sluggers did at the same age. Mickey Mantle—to whom Williams lost the MVP in ’57—retired at thirty-six. Oh, but the Mick’s a bad example, you say, because of his chronic knee problems and myriad of off-the-field issues? Fair enough. How about the man Williams was once almost traded for, Joe DiMaggio? He, too, retired at thirty-six. What about a center fielder known much more for his durability than the prior two—Willie Mays? At thirty-eight, the Say Hey Kid was a kid no more—he hit .283 with just thirteen home runs, and only had one twenty-plus homer season left in him. How about a man known throughout his career for his remarkable consistency—Hank Aaron? Hammerin’ Hank finally began to show some signs of age, hitting .265 with thirty-four home runs at thirty-eight. But, you ask, what about the greatest of them all? What about the legendary Babe Ruth? Even the Bambino was slowing down by thirty-eight, when he hit .301 with thirty-four homers—not bad, but certainly not Ruthian—and his lowest numbers in a full season in over a decade.

I could go on and on—look up almost any Hall of Famer, and take a peek at his numbers at age thirty-eight, and the story will undoubtedly remain the same—the signs of decline will be obvious, if the man was even fortunate enough to still be playing. But Williams is the exception.

Maybe the best way to describe his 1957 is “unimaginable”—it’s unimaginable, and before Williams did it, impossible, that a thirty-eight-year-old man could hit .388 and turn in one of the best offensive seasons in baseball history. But with a bat in his hands, the Splendid Splitter had a habit of making the previously unfathomable look routine, and ’57 was no exception.

|

66 |

THE MOST INCREDIBLE WORLD SERIES GAME FEATURING A TRIPLE PLAY |

It happened in Cleveland during the 1920 World Series between the Indians and Brooklyn. What transpired still boggles the mind, almost a century later. This was the fifth game for the championship in which unusual events began happening in the very first inning.

Elmer Smith hit a bases-loaded home run over the right field fence; it was the first of its kind in a World Series game. The second unique episode occurred during a Brooklyn rally in the fifth inning with runners on first and second. Clarence Mitchell was the batter when Robins manager Wilbert Robinson signaled for a hit-and-run play; as soon as Mitchell swung, the runners were to take off. Mitchell did as instructed, belting a searing line drive over second base. Indians second baseman Bill Wambsganss was so far from the base that he appeared unable to make a play for the hit. “But,” wrote Harry Cross in The New York Times, “Wambsganss leaped over toward the cushion, and with a mighty jump, speared the ball with one hand.” Pete Kilduff, the runner on second, was on his way to third and Miller, the runner from first, was almost within reach of second.

The quick-thinking Wambsganss touched second base, retiring Kilduff, who had almost reached third base. Meanwhile, Miller, who was trapped between first and second, appeared mummified by the proceedings and remained transfixed in his tracks. Wambsganss trotted over and tagged Miller for the third out. Thus, the first unassisted triple play was accomplished in the World Series. “The crowd,” reported Cross, “forgot it was hoarse of voice and close to nervous exhaustion, and gave Wamby just as great a reception as it had given Elmer Smith.”

If that wasn’t unusual enough, there was the added spectacle of Brooklyn pitcher Burleigh Grimes’ humiliation. “No pitcher,” wrote Cross, “has ever been kept in the box so long after he had started to slip. Uncle Robbie kept him on the mound for three and two-thirds innings, including two home runs and a triple.

“With a half a dozen able-bodied pitchers basking in the warm sun, Grimes was kept in the game until he was so badly battered that the game became a joke.”

When the score was 7–0, Grimes finally was removed.

In an ironic contrast, Cleveland pitcher Jim Bagby was hailed as a hero, even though no pitcher was ever before pounded for thirteen hits in a World Series. “He pitched,” wrote Cross, “what was really a bad game of ball, but when it was over he was proud of it.”

|

67 |

DICK GROAT—WILL IT BE BASKETBALL OR BASEBALL? |

There’s not much similarity between baseball and basketball, except for the fact that both balls involved are round.

As a result, it’s rare to find athletes who are competent enough to star in both sports. There was, however, one significant exception: Dick Groat, who ultimately starred with the Pittsburgh Pirates, St. Louis Cardinals, and the Philadelphia Phillies.

At five feet, eleven inches, Groat played one season in the National Basketball Association until he was faced with the choice of either professional baseball or basketball and went for the former. Groat wound up his fifteen-year MLB career with a lifetime batting average of .286 and was one of the best fielding shortstops in the majors during the 1960s.

|

68 |

THE ALL-TIME UTILITY PLAYER, MARTIN DIHIGO |

One of the unfortunate aspects of baseball history is that African American players did not appear in the major leagues until Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947.

Had the year been, say, 1847 and black players populated the top rung of baseball, Martin Dihigo would be a household name among diamond fans in the manner of a Babe Ruth or Lou Gehrig.

Starring in the American Negro League—among other circuits—Dihigo became known as the ultimate utility player.

Not only did Martin pitch, but he also played every position in the field, including catcher.

Martin Dihigo, according to many observers who saw him play in the 1920s and 1930s for the Cuban Stars and Homestead Grays, was one of the ultimate ballplayers of all time.

In a 1935 East-West All-Star game, Dihigo started in center field and batted third for the East, and, in the late innings, was called upon to pitch in relief. Buck Leonard, himself a star with the Grays, and others call Dihigo the greatest ballplayer of all-time. The Cubans and the Grays used him at every position, and in 1929 he batted .386 in the American Negro League.

When the Negro National League folded and blacks began to enter the major leagues, by this time Dihigo was too old to make it to the bigs, and he played out his career during the 1950s in Mexico.

|

69 |

THE LONGEST HOME RUN OUT OF YANKEE STADIUM |

When baseball historians rate the finest slugging catchers of any era, the name Josh Gibson invariably makes the list. The pity of it all is that he never played in the big leagues, since at the time it was composed of only Caucasian players.

As African American baseball stars go, Gibson ranks alongside Satchel Paige, Martin Dihigo, and another catcher who did make it into the National League, Roy Campanella.

How powerful a hitter was Gibson?

Quite simply, he did what no batter has ever accomplished at Yankee Stadium. Gibson hit this home run in a Negro National League game against the Philadelphia Stars.

Jack Marshall of the Chicago American Giants witnessed the feat: “Josh hit the ball over the triple deck next to the bullpen in left field. Over and out! I will never forget that because we were getting ready to leave because we were going to play a night game and we were standing in the aisle when that boy hit this ball!”

Baseball’s bible, The Sporting News, credits Gibson with hitting a longer home run than Ruth ever hit in the old Yankee Stadium, a drive that hit just two feet from the top of the stadium wall, circling the bleachers in center field, about 580 feet from home plate. It was estimated that had the blast been two feet higher it would have cleared the wall and traveled about seven hundred feet.

Walter Johnson, one of the best pitchers of all-time, watched Gibson in action and observed: “There is a catcher that any big-league club would like to buy for $200,000. His name is Gibson . . . He can do everything. He hits the ball a mile. And he catches so easy, he might as well be in a rocking chair. Throws like a rifle. Bill Dickey [the Yankee great] isn’t as good a catcher. Too bad this Gibson is a colored fellow.”

One legend has it that Gibson was playing at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh one day and hit such a towering drive that nobody saw it come down. After long deliberation, the umpire ruled it a home run. As the legend goes, a day later, Gibson’s team was playing in Philadelphia when suddenly a ball dropped out of the sky and was caught by an alert center fielder on the opposition. Pointing to Gibson, the umpire ruled: “You’re out—yesterday in Pittsburgh!”

|

70 |

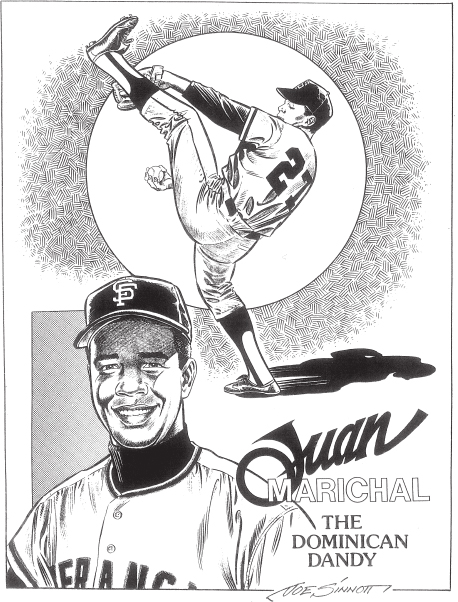

JUAN MARICHAL VS. WARREN SPAHN—DUEL OF THE TITANS |

There are many facets to classic baseball games, but none can top a pitchers’ battle.

Historians have a large selection from which to choose, but when it comes to hurlers’ bouts, the one that featured Juan Marichal and Warren Spahn rarely can be topped.

On July 2, 1963, two future Hall of Famers locked up for what may not have been the most dominating, but is certainly the most astonishing, pitchers’ duel of all time. One man, the twenty-five-year-old whirling dervish, Marichal, was at the height of his powers; the other, the forty-two-year-old Spahn, was a living legend, who, despite his age, was in the midst of winning twenty games for an unprecedented thirteenth time.

But, despite the extensive résumé of each man, no one in his/her wildest dreams could predict what would come next.

Over four hundred pitches were thrown as Juan Marichal’s Giants defeated Warren Spahn’s Braves 1–0 in sixteen innings, on the strength of a Willie Mays walk-off home run. The game was played in a brisk four hours and ten minutes—indicative of just how masterful each man was that day, and in about the same time as the average nine-inning Yankee-Red Sox tilt. And pitch counts? What pitch counts? Both men went the distance, and when it was all said and done, the final lines looked like this:

Marichal: 16 IP, 8 hits, 0 runs, 4 BB, 10 K

Spahn: 15.1 IP, 9 hits, 1 run, 1 BB, 2 K

Take a good, long look at that, boys and girls, because as long as baseball is played, you’ll never see another stat line like either of those. Nowadays, it would take many starters three outings to go as far as either man went in just one. Heck, it might take Phil Hughes a month.

Making this feat of human endurance all the more impressive are the formidable lineups Marichal and Spahn faced. In addition to the two starters, five men who would go on to earn busts in Cooperstown took the field that day: Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, and Orlando Cepeda of the Giants, and Hank Aaron and Eddie Mathews of the Braves.

San Francisco would lead the league in homers that year by a whopping fifty-eight over second-place Milwaukee. But, as the night progressed, the two hurlers continued to confound the legend-laden lineups opposing them: the southpaw Spahn, featuring the now-all-but-extinct screwball, and Marichal, with his dazzling array of pitches thrown from a variety of arm angles.

Neither man was in much trouble for most of the game. Marichal allowed three men in scoring position in the regulation nine innings—one of them Spahn, one of the greatest hitting pitchers of all time, who smoked a double off the wall—but stranded them all, with a little help from Willie Mays, who cut down a man at the plate in the fourth. Spahn, for his part, allowed a long drive to Willie McCovey in the bottom of the ninth that would’ve ended it, but it curved just foul (although McCovey, to this day, still disagrees with the umpire’s ruling). Nevertheless, baseball is a game of inches, and whether it was a blown call, a gust of wind, or a goose fart that caused that ball to be called foul, it allowed an already historic duel to become legendary.

Spahn was seemingly on the ropes in the fourteenth when he loaded the bases, but the splendid lefty worked out of the jam. Amazingly, but for the trouble Spahn encountered in the fourteenth, neither hurler showed any signs of fatigue as night turned into morning. In fact, it was the presence of the older Spahn that motivated the much younger Marichal to keep going. Giants manager Alvin Dark kept asking Marichal if he wanted out, causing the man with the highest leg kick in baseball to famously quip: “Alvin, do you see that man pitching on the other side? He’s forty-two and I’m twenty-five, and you can’t take me out until that man is not pitching.”

There’s no indication Spahn ever would’ve removed himself from the game had Mays not ended it, and in a classic “boy, has the game changed” moment, the old lefty was known to—and it’s unlikely this game was any exception—spend much of his time between innings smoking cigarettes in the runway behind the dugout.

To say we’ll never again see a sixteen-inning, 1–0 game where both pitchers go the distance—let alone one in which one starter is over forty—is the understatement of the century. That’s what makes Spahn and Marichal’s accomplishment so unbelievable.

As the role of innings limits and pitch counts continues to grow exponentially within the fabric of baseball, we look back in increasing disbelief at what Spahn and Marichal did in 1963. Their famous duel ages like fine wine. Years later, even Spahn—in a clear indication that he understood the significance of that famous game—would remark to his son, Greg, that of the countless pitches he threw in his twenty-one-year career, it was the last pitch, that July morning, that he regretted the most. Recalled Greg: “That pitch probably bothered him more than any he ever threw. For years he said that if he had one pitch he’d like to take back, that was it.”

|

71 |

BOB GIBSON’S FABULOUS 1968 SEASON |

Mention the name Bob Gibson to almost any batter who faced the St. Louis Cardinals fireballer, and he will tell you the first word that comes to mind: intimidation.

Few hurlers could put more fear in the hearts of the most courageous batters than Gibson.

In the history of Major League Baseball, there are certain individual seasons that stand above the rest: Babe Ruth’s 1921, Ted Williams’ 1941, and, yes, Bob Gibson’s 1968—the holy grail of all pitching seasons.

In 1968, Bob Gibson was 22–9, with a 1.12 ERA—a live-ball era record, twenty-eight complete games, thirteen shutouts—also a live-ball era record, and a miniscule .853 WHIP.

Imagine if, in addition to hitting .406 in 1941, Ted Williams also slugged sixty-one home runs—that’s basically what Gibson did in ’68. He was utterly dominant, to a degree no one had ever seen before, and hasn’t been touched since.

Gibson’s 1.12 ERA is almost a half-point better than the next-best mark recorded in the live-ball era—Greg Maddux’s 1.56 in 1994. Furthermore, Maddux only made twenty-five starts that season, making it likely that number would have gone up had he pitched a full slate of games. Yet, the 1.12 doesn’t even begin to tell the whole story.

Nestled inside the 304.2 innings Gibson tossed that year is perhaps the most dominant stretch a pitcher has ever had. From June 2 through July 30, Gibson threw ninety-nine innings and gave up a ludicrous two runs. That’s a 0.27 ERA in what amounts to, in modern times, essentially half a season’s worth of innings.

All things considered, perhaps the most baffling thing about Gibson’s 1968 is that he somehow lost nine games. The biggest detriment to Gibson’s greatness that season is that 1968 is commonly referred to as the “year of the pitcher.” Pitching was so dominant that year, the mound was lowered the next season.

But punishing Gibson for being so devastating in 1968 would be like punishing Babe Ruth for not hitting sixty home runs in the dead-ball era; “Well, yeah, sixty's great, but it’s not like he did it when home runs were hard to hit.” Sound ridiculous? Thought so.

The fact is, Gibson was still head and shoulders the best pitcher in the league. His ERA was a half-point lower than his closest competitor, he tossed four more shutouts than anyone in the league, and his WAR was nearly a full three points higher than any other pitcher (11.2 to Luis Tiant’s 8.4).

If that’s not enough, Gibson turned in one of the most dominant performances in World Series history in ’68. In Game One of the Fall Classic, Gibson tossed a complete game shutout, striking out seventeen baffled Detroit Tigers, while allowing just five hits and walking one.

The seventeen K’s is a World Series record that still stands. There aren’t many certainties in sports, but I am certain that as long as I live, I will never see a pitcher have a season like Bob Gibson did in 1968.

|

72 |

A GOOSE EGG TRIFECTA FORGOTTEN BY MANY |

You won’t hear the name Christy Mathewson bruited around much anymore, simply because he was a pitcher who starred early in the twentieth century.

His exploits—many extraordinary—put baseball on the map in the early 1900s when he was the ace of the New York Giants pitching staff.

Many historians will tell you that Matty’s performance in the 1905 Series between John McGraw’s Giants and Connie Mack’s Athletics never will be matched.

On October 9, 12, and 14, 1905, Mathewson threw three shutouts in a span of six days, in a series of only five games, a record that still stands today, over one hundred years later.

The three goose eggs enabled the New Yorkers to defeat Philadelphia four games to one. Joe McGinnity won the other game for the Giants in the same fashion as Mathewson: a shutout as well.

The World Series of 1907 was disappointing in only one respect. The heralded pitching duels between the brilliant, but erratic, Rube Waddell and Mathewson never materialized.

The great Philadelphia southpaw was injured in some horseplay on a railroad platform, while the A’s were celebrating the clinching of the American League pennant in Boston. As a result, he was unable to pitch in the Series against the Giants.

|

73 |

SHORT HITS—FOR NINE MEN IN THE FIELD, NINE SHORT TALES OF INCREDULITY |

Author’s Note: From 1990 through the present, there have been some extraordinary events on the field and off. Here are nine for your enjoyment:

A) Rickey Henderson Breaks Lou Brock’s Stolen Base Record (1991)

Rickey Henderson became synonymous with the stolen base over the course of his long career. In 1982, Henderson stole over 130 bases, more than eleven entire teams’ totals for the season. On May 1, 1991, the greatest base-stealer on the planet broke Lou Brock’s career record when he stole third against the Yankees. Henderson passed Brock in just eleven big league seasons, while it took Brock nineteen years to master the feat.

B) JACK MORRIS THROWS TEN SHUTOUT INNINGS IN WORLD SERIES GAME SEVEN (1991)

The World Series of 1991 featured one of the greatest pitching matchups of all time. Amazingly, both teams finished in last place the year before, and never before had a team gone from last place to the World Series.

In Game Seven, Jack Morris squared off against John Smoltz, and it was Morris who came out on top, pitching ten shutout innings to lead Minnesota to the title. Not only was it the first 1–0 Game Seven finish since 1962, but also it was the first Game Seven since 1924 in which the hosts walked off with the victory in the bottom of an extra inning.

C) Joe Carter’s Walk-off World Series Home Run (1993)

Only two players in Major League Baseball history have hit a walk-off home run to win a World Series. Bill Mazeroski beat the Yankees with his walk-off homer for the Pirates in the 1960 World Series, and in 1993, Joe Carter’s homer off Phillies closer Mitch Williams gave the Toronto Blue Jays the World Championship.

Carter’s historic blast remains the only come-from-behind, walk-off World Series-winning home run.

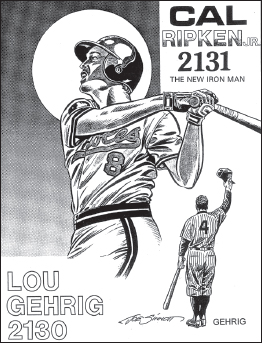

D) Cal Ripken Passes Lou Gehrig (1995)

Nobody ever thought that Lou Gehrig’s iron-man record would ever be broken. Gehrig’s record of 2,130 consecutive games played was thought to be one of those records deemed unbreakable, but Cal Ripken Jr. came along and did the unthinkable.

Throughout the 1995 season, the Orioles draped numbers on the B&O Warehouse in right field to record Ripken’s streak. Finally, on September 6, in a game against the California Angels, Ripken passed the “Iron Horse,” and now that record is pretty much unattainable.

E) Baseball RETURNS TO New York After 9/11 (2001)

The Major League Baseball season was reaching the homestretch when the 9/11 attacks took place, but Commissioner Bud Selig understandably shut down the game. When play resumed in New York on September 21, the Mets were home to take on the Atlanta Braves, in what was the first major sporting event in New York since the attacks.

The Mets and Braves had been longtime rivals, and despite the air that this particular game took on, it was still a tense, 1–1 affair through seven innings. That all changed when a one-out eighth-inning walk brought up Mike Piazza. Everybody knows what happened next, as the power-hitting catcher launched a 0–1 pitch deep over the center field fence to put the Mets ahead for good and launching an enormous celebration.

F) LUIS GONZALEZ DELIVERS WORLD SERIES TITLE TO THE DESERT (2001)

The 2001 World Series was one of the greatest World Series to ever be played. The most storied franchise in Major League history was trying to four-peat against a team that had been in existence for just four years.

These playoffs took on an even bigger significance for the Yankees, as they were playing for their city. With the city still recovering from the 9/11 attacks, Yankee games provided a much-needed distraction for New Yorkers.

The Bronx Bombers took a 2–0 deficit back to the Bronx, but they went on to win the next three games, with two of the wins coming in dramatic fashion against Arizona’s closer Byung-Hyun Kim. The Diamondbacks bounced back to win Game Six and force a Game Seven, where the Yankees took a 2–1 lead to the eighth inning.

With Mariano Rivera coming into the game, another ring was all but a done-deal. Rivera breezed through the eighth inning by striking out the side. But then, the unimaginable happened. A lead-off Mark Grace single would set up a rally for the ages. Arizona would eventually load the bases to bring up Luis Gonzalez, their best hitter. With the Yankees’ infield and outfield drawn in, Gonzalez blooped a ball over a drawn-in Derek Jeter to deliver the World Series title to Arizona.

G) Derek Jeter’s flip (2001)

Derek Jeter’s name sits atop the Yankee “Mount Rushmore,” with the likes of Ruth, Gehrig, DiMaggio, and Mantle, for a number of feats. Over the years, he has had countless clutch hits, and he was even nicknamed “Mr. November” during the 2001 postseason. During that same playoff run, Jeter made one of the most brilliant defensive plays ever, in Oakland.

With the Athletics leading the five-game divisional series two games to none, on the verge of completing a sweep, the Yankees took a 1–0 lead into the bottom of the seventh inning behind a strong performance from Mike Mussina.

With two outs and Jeremy Giambi on first base, Terrence Long hit a line drive into the right field corner. With Giambi rounding third base, right fielder Shane Spencer’s throw sailed over both cut-off men, and it appeared that Giambi would score easily. But Jeter came out of nowhere and changed the momentum of the series with the famously known “Flip” play.

After the game, Jeter told the press that the team had been practicing this type of play all year as a result of a similarly botched throw in spring training. The idea of stationing the shortstop down the first base line on balls hit to deep right field came from Yankees bench coach, Don Zimmer.

H) HALL OF FAMERS BABE RUTH AND TY COBB’S SHARED IDOL

The renowned sluggers admitted that they revered shoeless Joe Jackson’s swing so much that they watched him when they were win a slump. Shoeless Joe ranked third on the all-time batting average list with an average of .356.

I) Roy Halladay’s NLDS No-Hitter (2010)

After never making it to the postseason as a member of the Toronto Blue Jays, Roy Halladay was ready for baseball’s biggest stage. Halladay wanted to be a member of the Philadelphia Phillies so he could chase a Championship, and in his first postseason game, he threw just the second postseason no-hitter ever and first since Don Larsen’s 1956 perfect game.

|

74 |

THE CATCHER WHO COST THE PHILLIES $10,000 FOR RUNNING TOO FAST |

This one really strains credulity, but it actually happened. It’s all about a second-string catcher on the Philadelphia Phillies, who cost his club ten grand simply by not thinking.

Here’s how this bizarre scenario unfolded.

On June 8, 1947, the Pirates and Phillies were tied in Philadelphia at 4–4 in the eighth inning. Then, in the top of the ninth, Pirate Ralph Kiner hit a home run.

It was nearly 7 p.m., and there was an early curfew in Philadelphia. If the game did not end by 7 p.m., the score reverted to the last complete inning. If there was a tie, the game would be replayed the next day as part of a doubleheader.

Both the Pirates and the Phillies were aware of this. The Pirates had little desire to play a doubleheader, but the Phillies wanted the extra $10,000 in admission tickets that a doubleheader would bring. In order to hasten the outcome of the game, the Pirates’ Hank Greenberg allowed himself to be out.

When the Phillies came up, Manager Ben Chapman told his men to delay as much as possible. The first man popped out. The second man, Charley Gilbert, a pinch hitter, took an excessively long time to select a bat. Then he argued with umpire Babe Pinelli, intentionally fouled off some pitches, and finally struck out. One more out and the Phillies would lose both the game and the $10,000 gate money from a doubleheader.

Chapman called for second-string catcher Hugh Poland, stationed three hundred feet away in the bullpen, to hit, anticipating that Poland would take some time to come in, eating up the clock.

Much to Chapman’s dismay, Poland ran in without realizing that the purpose of his appearance was to delay the game.

When Poland arrived, he saw that he had to counteract his dash. He argued briefly with Umpire Pinelli, but Pinelli hurried him back to the box.

Poland took two strikes and then hit a lazy fly ball, which Pirate Wally Westlake caught—fifty-two seconds before curfew. The Phillies lost the game—and the $10,000.