In the last years of the community, the island Parliament often declared itself to be in extraordinary session. On these occasions, the sole item on the agenda was concerned with improving their economic conditions and securing the future of the population by encouraging others to move to Village Bay. One time, in order to do this, they decided to hire a marketing consultant. The gentleman arrived in Parliament and suggested the following advertising slogans to aid their campaign for survival:

‘Eat Fresh; Eat Fulmar’

‘Pick Up A Puffin...’

‘You do the shoogle vac to lift the feather sack…’

‘Guga Is Good For You’.

In order to illustrate the last catchphrase, the marketing man decided to create the image of a gannet, complete with white plumage and black-tipped wings. This was to be inscribed on the outside of a glass of Irish stout.

As they were teetotal, the islanders completely rejected this suggestion, believing it might give the wrong impression of the kind of new arrival they were seeking for their shores.

‘You should extend your range of gifts,’ the marketing consultant advised them.

He flourished a hand over those items that already existed; the lengths of tweed woven over the winter; the cuddly puffins and gannets created for a child to cuddle under eiderdown; the buxom Murdina Gillies ® doll equipped with tartan shawl and a creelful of peat as essential fashion accessories.

‘What do you suggest?’ one of the islanders growled.

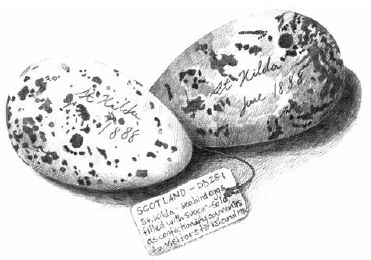

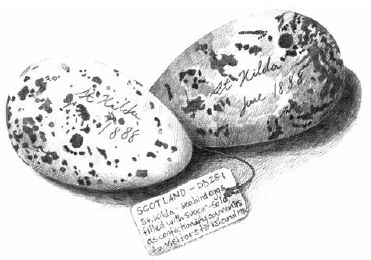

‘We could improve upon your selling of guillemot and razorbill eggs. Make a hole in them. Blow them out. Fill their empty shells with granulated sugar and glucose syrup. Market them just like the sticks of rock they sell in Blackpool…’

‘According to a Government directive,’ old Gillies declared one day in Parliament, ‘we should be investing more in renewables.’

‘We’ve got plenty of possibilities,’ Macdonald said. ‘Wind…’

‘Tide…’

‘Wave…’

‘What about the fulmars?’ Ferguson asked. ‘We could be dealing with them in a different way.’

‘How?’ old Gillies growled.

‘Employ a special fulmar-agitator on these cliffs. Get the birds to spit at them and squeeze all of the oil out of their coats, trousers, beards…’

When old Gillies was finally ‘going over’, the others gathered round him; young Ferguson noting each word he gasped out in the pages of an old school jotter.

‘In August that year, we went out to the stac, harvested a thousand birds…’

‘In May, we sold souvenirs to the tourists… Five good lengths of tweed…’

‘We gathered three hundred fulmar eggs that day…’

‘Why are you doing that to him?’ the nurse asked, horrified at their cruelty. ‘Can’t you see the poor man’s dying?’

‘We have to do this,’ Ferguson muttered. ‘He keeps the records of all we’ve discussed in Parliament. They’re all contained inside his head.’

‘He’s sort of our Hansard…’ Malcolm Macdonald explained.

One fine summer’s morning proceedings carried on longer than usual.

To begin with, Angus B arrived late, his clothes smarter than usual, his hair neatly combed by a fish-skeleton. After that, he proceeded to talk endlessly about irrelevant matters – the candelabra in the Turkish embassy, changing the rules of the game of football, the distance and nature of the arc birds flew between Ireland and Iceland, the cost of storm petrel oil in the Faroe Islands.

‘He’s trying for a filibuster,’ Ferguson muttered, ‘He doesn’t want to do any work today.’