Chapter X

A WARM WELCOME

The day grew lighter and warmer as they floated along. After a while the river rounded a steep shoulder of land that came down upon their left. Under its rocky feet like an inland cliff the deepest stream had flowed lapping and bubbling. Suddenly the cliff fell away. The shores sank. The trees ended. Then Bilbo saw a sight:

The lands opened wide about him, filled with the waters of the river which broke up and wandered in a hundred winding courses, or halted in marshes and pools dotted with isles on every side; but still a strong water flowed on steadily through the midst. And far away, its dark head in a torn cloud, there loomed the Mountain! Its nearest neighbours to the North-East and the tumbled land that joined it to them could not be seen. All alone it rose and looked across the marshes to the forest. The Lonely Mountain! Bilbo had come far and through many adventures to see it, and now he did not like the look of it in the least.

As he listened to the talk of the raftmen and pieced together the scraps of information they let fall, he soon realized that he was very fortunate ever to have seen it at all, even from this distance. Dreary as had been his imprisonment and unpleasant as was his position (to say nothing of the poor dwarves underneath him) still, he had been more lucky than he had guessed. The talk was all of the trade that came and went on the waterways and the growth of the traffic on the river, as the roads out of the East towards Mirkwood vanished or fell into disuse; and of the bickerings of the Lake-men and the Wood-elves about the upkeep of the Forest River and the care of the banks. Those lands had changed much since the days when dwarves dwelt in the Mountain, days which most people now remembered only as a very shadowy tradition. They had changed even in recent years, and since the last news that Gandalf had had of them. Great floods and rains had swollen the waters that flowed east; and there had been an earthquake or two (which some were inclined to attribute to the dragon—alluding to him chiefly with a curse and an ominous nod in the direction of the Mountain). The marshes and bogs had spread wider and wider on either side. Paths had vanished, and many a rider and wanderer too, if they had tried to find the lost ways across. The elf-road through the wood which the dwarves had followed on the advice of Beorn now came to a doubtful and little used end at the eastern edge of the forest; only the river offered any longer a safe way from the skirts of Mirkwood in the North to the mountain-shadowed plains beyond, and the river was guarded by the Wood-elves’ king.

So you see Bilbo had come in the end by the only road that was any good. It might have been some comfort to Mr. Baggins shivering on the barrels, if he had known that news of this had reached Gandalf far away and given him great anxiety, and that he was in fact finishing his other business (which does not come into this tale) and getting ready to come in search of Thorin’s company. But Bilbo did not know it.

All he knew was that the river seemed to go on and on and on for ever, and he was hungry, and had a nasty cold in the nose, and did not like the way the Mountain seemed to frown at him and threaten him as it drew ever nearer. After a while, however, the river took a more southerly course and the Mountain receded again, and at last, late in the day the shores grew rocky, the river gathered all its wandering waters together into a deep and rapid flood, and they swept along at great speed.

The sun had set when turning with another sweep towards the East the forest-river rushed into the Long Lake. There it had a wide mouth with stony clifflike gates at either side whose feet were piled with shingles. The Long Lake! Bilbo had never imagined that any water that was not the sea could look so big. It was so wide that the opposite shores looked small and far, but it was so long that its northerly end, which pointed towards the Mountain, could not be seen at all. Only from the map did Bilbo know that away up there, where the stars of the Wain were already twinkling, the Running River came down into the lake from Dale and with the Forest River filled with deep waters what must once have been a great deep rocky valley. At the southern end the doubled waters poured out again over high waterfalls and ran away hurriedly to unknown lands. In the still evening air the noise of the falls could be heard like a distant roar.

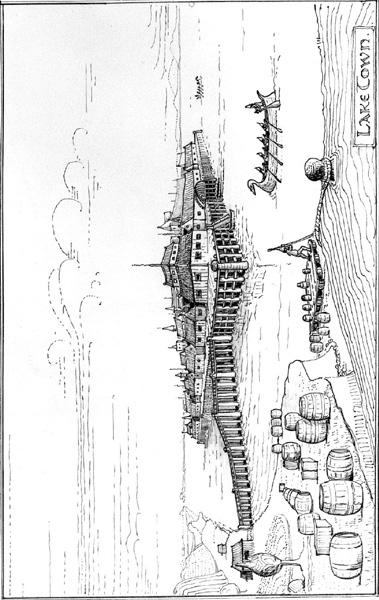

Not far from the mouth of the Forest River was the strange town he heard the elves speak of in the king’s cellars. It was not built on the shore, though there were a few huts and buildings there, but right out on the surface of the lake, protected from the swirl of the entering river by a promontory of rock which formed a calm bay. A great bridge made of wood ran out to where on huge piles made of forest trees was built a busy wooden town, not a town of elves but of Men, who still dared to dwell here under the shadow of the distant dragon-mountain. They still throve on the trade that came up the great river from the South and was carted past the falls to their town; but in the great days of old, when Dale in the North was rich and prosperous, they had been wealthy and powerful, and there had been fleets of boats on the waters, and some were filled with gold and some with warriors in armour, and there had been wars and deeds which were now only a legend. The rotting piles of a greater town could still be seen along the shores when the waters sank in a drought.

But men remembered little of all that, though some still sang old songs of the dwarf-kings of the Mountain, Thror and Thrain of the race of Durin, and of the coming of the Dragon, and the fall of the lords of Dale. Some sang too that Thror and Thrain would come back one day and gold would flow in rivers, through the mountain-gates, and all that land would be filled with new song and new laughter. But this pleasant legend did not much affect their daily business.

As soon as the raft of barrels came in sight boats rowed out from the piles of the town, and voices hailed the raft-steerers. Then ropes were cast and oars were pulled, and soon the raft was drawn out of the current of the Forest River and towed away round the high shoulder of rock into the little bay of Lake-town. There it was moored not far from the shoreward head of the great bridge. Soon men would come up from the South and take some of the casks away, and others they would fill with goods they had brought to be taken back up the stream to the Wood-elves’ home. In the meanwhile the barrels were left afloat while the elves of the raft and the boatmen went to feast in Lake-town.

They would have been surprised, if they could have seen what happened down by the shore, after they had gone and the shades of night had fallen. First of all a barrel was cut loose by Bilbo and pushed to the shore and opened. Groans came from inside, and out crept a most unhappy dwarf. Wet straw was in his draggled beard; he was so sore and stiff, so bruised and buffeted he could hardly stand or stumble through the shallow water to lie groaning on the shore. He had a famished and a savage look like a dog that has been chained and forgotten in a kennel for a week. It was Thorin, but you could only have told it by his golden chain, and by the colour of his now dirty and tattered sky-blue hood with its tarnished silver tassel. It was some time before he would be even polite to the hobbit.

“Well, are you alive or are you dead?” asked Bilbo quite crossly. Perhaps he had forgotten that he had had at least one good meal more than the dwarves, and also the use of his arms and legs, not to speak of a greater allowance of air. “Are you still in prison, or are you free? If you want food, and if you want to go on with this silly adventure—it’s yours after all and not mine—you had better slap your arms and rub your legs and try and help me get the others out while there is a chance!”

Thorin of course saw the sense of this, so after a few more groans he got up and helped the hobbit as well as he could. In the darkness floundering in the cold water they had a difficult and very nasty job finding which were the right barrels. Knocking outside and calling only discovered about six dwarves that could answer. These were unpacked and helped ashore where they sat or lay muttering and moaning; they were so soaked and bruised and cramped that they could hardly yet realize their release or be properly thankful for it.

Dwalin and Balin were two of the most unhappy, and it was no good asking them to help. Bifur and Bofur were less knocked about and drier, but they lay down and would do nothing. Fili and Kili, however, who were young (for dwarves) and had also been packed more neatly with plenty of straw into smaller casks, came out more or less smiling, with only a bruise or two and a stiffness that soon wore off.

“I hope I never smell the smell of apples again!” said Fili. “My tub was full of it. To smell apples everlastingly when you can scarcely move and are cold and sick with hunger is maddening. I could eat anything in the wide world now, for hours on end—but not an apple!”

With the willing help of Fili and Kili, Thorin and Bilbo at last discovered the remainder of the company and got them out. Poor fat Bombur was asleep or senseless; Dori, Nori, Ori, Oin and Gloin were waterlogged and seemed only half alive; they all had to be carried one by one and laid helpless on the shore.

“Well! Here we are!” said Thorin. “And I suppose we ought to thank our stars and Mr. Baggins. I am sure he has a right to expect it, though I wish he could have arranged a more comfortable journey. Still—all very much at your service once more, Mr. Baggins. No doubt we shall feel properly grateful, when we are fed and recovered. In the meanwhile what next?”

“I suggest Lake-town,” said Bilbo. “What else is there?”

Nothing else could, of course, be suggested; so leaving the others Thorin and Fili and Kili and the hobbit went along the shore to the great bridge. There were guards at the head of it, but they were not keeping very careful watch, for it was so long since there had been any real need. Except for occasional squabbles about river-tolls they were friends with the Wood-elves. Other folk were far away; and some of the younger people in the town openly doubted the existence of any dragon in the mountain, and laughed at the greybeards and gammers who said that they had seen him flying in the sky in their young days. That being so it is not surprising that the guards were drinking and laughing by a fire in their hut, and did not hear the noise of the unpacking of the dwarves or the footsteps of the four scouts. Their astonishment was enormous when Thorin Oakenshield stepped in through the door.

“Who are you and what do you want?” they shouted leaping to their feet and groping for weapons.

“Thorin son of Thrain son of Thror King under the Mountain!” said the dwarf in a loud voice, and he looked it, in spite of his torn clothes and draggled hood. The gold gleamed on his neck and waist; his eyes were dark and deep. “I have come back. I wish to see the Master of your town!”

Then there was tremendous excitement. Some of the more foolish ran out of the hut as if they expected the Mountain to go golden in the night and all the waters of the lake turn yellow right away. The captain of the guard came forward.

“And who are these?” he asked, pointing to Fili and Kili and Bilbo.

“The sons of my father’s daughter,” answered Thorin, “Fili and Kili of the race of Durin, and Mr. Baggins who has travelled with us out of the West.”

“If you come in peace lay down your arms!” said the captain.

“We have none,” said Thorin, and it was true enough: their knives had been taken from them by the wood-elves, and the great sword Orcrist too. Bilbo had his short sword, hidden as usual, but he said nothing about that. “We have no need of weapons, who return at last to our own as spoken of old. Nor could we fight against so many. Take us to your master!”

“He is at feast,” said the captain.

“Then all the more reason for taking us to him,” burst in Fili, who was getting impatient at these solemnities. “We are worn and famished after our long road and we have sick comrades. Now make haste and let us have no more words, or your master may have something to say to you.”

“Follow me then,” said the captain, and with six men about them he led them over the bridge through the gates and into the market-place of the town. This was a wide circle of quiet water surrounded by the tall piles on which were built the greater houses, and by long wooden quays with many steps and ladders going down to the surface of the lake. From one great hall shone many lights and there came the sound of many voices. They passed its doors and stood blinking in the light looking at long tables filled with folk.

“I am Thorin son of Thrain son of Thror King under the Mountain! I return!” cried Thorin in a loud voice from the door, before the captain could say anything.

All leaped to their feet. The Master of the town sprang from his great chair. But none rose in greater surprise than the raft-men of the elves who were sitting at the lower end of the hall. Pressing forward before the Master’s table they cried:

“These are prisoners of our king that have escaped, wandering vagabond dwarves that could not give any good account of themselves, sneaking through the woods and molesting our people!”

“Is this true?” asked the Master. As a matter of fact he thought it far more likely than the return of the King under the Mountain, if any such person had ever existed.

“It is true that we were wrongfully waylaid by the Elvenking and imprisoned without cause as we journeyed back to our own land,” answered Thorin. “But lock nor bar may hinder the homecoming spoken of old. Nor is this town in the Wood-elves’ realm. I speak to the Master of the town of the Men of the Lake, not to the raft-men of the king.”

Then the Master hesitated and looked from one to the other. The Elvenking was very powerful in those parts and the Master wished for no enmity with him, nor did he think much of old songs, giving his mind to trade and tolls, to cargoes and gold, to which habit he owed his position. Others were of different mind, however, and quickly the matter was settled without him. The news had spread from the doors of the hall like fire through all the town. People were shouting inside the hall and outside it. The quays were thronged with hurrying feet. Some began to sing snatches of old songs concerning the return of the King under the Mountain; that it was Thror’s grandson not Thror himself that had come back did not bother them at all. Others took up the song and it rolled loud and high over the lake.

The King beneath the mountains,

The King of carven stone,

The lord of silver fountains

Shall come into his own!

His crown shall be upholden,

His harp shall be restrung,

His halls shall echo golden

To songs of yore re-sung.

The woods shall wave on mountains

And grass beneath the sun;

His wealth shall flow in fountains

And the rivers golden run.

The streams shall run in gladness,

The lakes shall shine and burn,

All sorrow fail and sadness

At the Mountain-king’s return!

So they sang, or very like that, only there was a great deal more of it, and there was much shouting as well as the music of harps and of fiddles mixed up with it. Indeed such excitement had not been known in the town in the memory of the oldest grandfather. The Wood-elves themselves began to wonder greatly and even to be afraid. They did not know of course how Thorin had escaped, and they began to think their king might have made a serious mistake. As for the Master he saw there was nothing else for it but to obey the general clamour, for the moment at any rate, and to pretend to believe that Thorin was what he said. So he gave up to him his own great chair and set Fili and Kili beside him in places of honour. Even Bilbo was given a seat at the high table, and no explanation of where he came in—no songs had alluded to him even in the obscurest way—was asked for in the general bustle.

Soon afterwards the other dwarves were brought into the town amid scenes of astonishing enthusiasm. They were all doctored and fed and housed and pampered in the most delightful and satisfactory fashion. A large house was given up to Thorin and his company; boats and rowers were put at their service; and crowds sat outside and sang songs all day, or cheered if any dwarf showed so much as his nose.

Some of the songs were old ones; but some of them were quite new and spoke confidently of the sudden death of the dragon and of cargoes of rich presents coming down the river to Lake-town. These were inspired largely by the Master and they did not particularly please the dwarves, but in the meantime they were well contented and they quickly grew fat and strong again. Indeed within a week they were quite recovered, fitted out in fine cloth of their proper colours, with beards combed and trimmed, and proud steps. Thorin looked and walked as if his kingdom was already regained and Smaug chopped up into little pieces.

Then, as he had said, the dwarves’ good feeling towards the little hobbit grew stronger every day. There were no more groans or grumbles. They drank his health, and they patted him on the back, and they made a great fuss of him; which was just as well, for he was not feeling particularly cheerful. He had not forgotten the look of the Mountain, nor the thought of the dragon, and he had besides a shocking cold. For three days he sneezed and coughed, and he could not go out, and even after that his speeches at banquets were limited to “Thag you very buch.”

In the meanwhile the Wood-elves had gone back up the Forest River with their cargoes, and there was great excitement in the king’s palace. I have never heard what happened to the chief of the guards and the butler. Nothing of course was ever said about keys or barrels while the dwarves stayed in Lake-town, and Bilbo was careful never to become invisible. Still, I daresay, more was guessed than was known, though doubtless Mr. Baggins remained a bit of a mystery. In any case the king knew now the dwarves’ errand, or thought he did, and he said to himself:

“Very well! We’ll see! No treasure will come back through Mirkwood without my having something to say in the matter. But I expect they will all come to a bad end, and serve them right!” He at any rate did not believe in dwarves fighting and killing dragons like Smaug, and he strongly suspected attempted burglary or something like it—which shows he was a wise elf and wiser than the men of the town, though not quite right, as we shall see in the end. He sent out his spies about the shores of the lake and as far northward towards the Mountain as they would go, and waited.

At the end of a fortnight Thorin began to think of departure. While the enthusiasm still lasted in the town was the time to get help. It would not do to let everything cool down with delay. So he spoke to the Master and his councillors and said that soon he and his company must go on towards the Mountain.

Then for the first time the Master was surprised and a little frightened; and he wondered if Thorin was after all really a descendant of the old kings. He had never thought that the dwarves would actually dare to approach Smaug, but believed they were frauds who would sooner or later be discovered and be turned out. He was wrong. Thorin, of course, was really the grandson of the King under the Mountain, and there is no knowing what a dwarf will not dare and do for revenge or the recovery of his own.

But the Master was not sorry at all to let them go. They were expensive to keep, and their arrival had turned things into a long holiday in which business was at a standstill. “Let them go and bother Smaug, and see how he welcomes them!” he thought. “Certainly, O Thorin Thrain’s son Thror’s son!” was what he said. “You must claim your own. The hour is at hand, spoken of old. What help we can offer shall be yours, and we trust to your gratitude when your kingdom is regained.”

So one day, although autumn was now getting far on, and winds were cold, and leaves were falling fast, three large boats left Lake-town, laden with rowers, dwarves, Mr. Baggins, and many provisions. Horses and ponies had been sent round by circuitous paths to meet them at their appointed landing-place. The Master and his councillors bade them farewell from the great steps of the town-hall that went down to the lake. People sang on the quays and out of windows. The white oars dipped and splashed, and off they went north up the lake on the last stage of their long journey. The only person thoroughly unhappy was Bilbo.