Northeast of Atlanta, a little over thirty miles beyond the university town of Athens, lies the tiny city of Elberton, Georgia. Founded in 1803, the town was originally named “Elbertville” after General Samuel Elbert, who fought in the American Revolutionary War. Today it is the county seat of Elbert County and the self-proclaimed “Granite Capital of the World,” producing more granite monuments than any other city worldwide. But despite that distinction, it is a relatively quiet little town, hosting a population of only 4,54616 within the four square miles of the city proper. It is not the kind of place that one would expect to be at the heart of a controversial mystery, but since the Georgia Guidestones were built in 1979, that is exactly what it has been.

The array of granite stones standing just off U.S. Highway 77 has drawn both criticism and acclaim from tourists who have come to visit it. Throughout the world, those who are aware of the monument have voiced opinions about it that cover a broad spectrum. Some have openly called for the “satanic” monument’s destruction, while others believe that it should be protected as a beacon of peace. This extreme diversity of perspective also exists among the residents of Elbert County, Georgia, a microcosm of the wide world that surrounds it.

The debate began almost immediately.

On March 22, 1980, Mayor Jack Wheeler and Rep. Doug Barnard, Jr. (D-GA) stood on a windy hill in northeast Georgia and cut a rope. Its binding gone, an enormous sheet of black plastic fell to the ground and revealed the new landmark it had been covering. Six slabs of solid granite, engraved with writings in twelve languages, towered above the gathered crowd. No one cheered.

The mayor and the congressman each spoke a piece about the monument. A passage from a letter written by the mysterious founder, R. C. Christian, was read to the crowd. Then William G. Hutton, who was at that time the president of the Monument Builders of North America, stepped forward to say a few words.

The Guidestones are what may be one of the few lasting mementos of a civilization that some thousands of years hence may not exist. It would be very interesting to hear the remarks if some future resident of that far-off time, say in the year 3586, happens upon them and deciphers one or more of the stones and says something like, “I wonder what went wrong here?”17

The crowd shifted uncomfortably as he spoke. Though they had all read in the local paper that the purported purpose of the monument was to act as a beacon to survivors of a possible global catastrophe, not all of them believed this to be true. The sponsor’s anonymity and the strange words etched into the stones had given rise to fear and suspicion in many hearts. There were rumors that the Guidestones had a more sinister meaning.

After the ceremony, the visitors had a chance to examine the new local attraction more closely. They milled about the site, sampling the refreshments provided and talking to the local reporters who had attended to cover the event. One man in particular drew a small crowd around him as he discussed his opinions with a writer from Brown’s Guide to Georgia.

“Some of my congregation feel the same way I do,” said the Reverend James Traffensted of the Elberton Church of God. “We don’t think Mr. Christian is a Christian.”18 A few murmurs and nods from the people around him confirmed that this worry was shared.

Look what it says about the unity of the world, especially with the world court. That’s where the Antichrist will unite the governments of the world under his power, the power of the devil … They seem so innocent in outward appearance, but the scripture teaches that there will be seducing spirits and doctrines of devils in the last days, according to Paul … I think they will find this monument is for sun worshipers, for cult worship and devil worship.19

Traffensted, like some of the other Christians in Elberton, was very concerned by aspects of the monument that he perceived as satanic. The presence of foreign languages on the stones, the frequent references to nature, and the landmark’s strong resemblance to Stonehenge all combined to present an unsettling image in the minds of some of the townsfolk.

As he was the only man to know the real identity of the Guidestones’ strange backer, R. C. Christian, banker Wyatt Martin was often approached by the concerned citizens of Elberton who felt the monument was an “evil thing,”20 especially in the early years. He did his best to set their minds to ease, but it was no simple task. “In the Bible,” he explains, “we find instances where children were actually burned or killed in dedication to strange gods. And they had the idea this was going to happen up there … But it was never meant for that.”21

Regardless of the intentions of the founder, however, local pagan groups have held rituals at the site—though there is no evidence that there has ever been anything so dramatic as a human sacrifice anywhere on the grounds. There were even some local occultists present for the dedication ceremony. Self-described “psychic,” Nonnie Wright Bakelder attended the unveiling specifically because she felt that there was something inherently magical about the site, but she did not see that as a bad thing. The land that the Georgia Guidestones stands upon, she claimed, has a “very high form of energy, a special energy—some would call it a vortex or a power spot.”22 According to Bakelder, this energy theoretically could be harnessed by a magician or witch and channeled into a ritual.

But, at least according to the official story, R. C. Christian did not select the location for the monument by himself. Wyatt Martin claims that he himself sought out and found three potentially suitable properties and presented them to the mystery man as options. Of the three alternatives, Mr. Christian decided upon the pasture of Wayne Mullenix’s Double Seven Ranch, but Martin insists that “any connection between the site chosen and occult indications is purely coincidental.”23

But it was not the apparently “energetic” location that raised eyebrows with the locals. It was the actual guides on the Guidestones and even its overall design that caused alarm in some circles. An associate of Reverend Traffensted, the Reverend Cecil McQuaig claimed not long after the dedication that the monument was “beyond any doubt the work of a group dedicated to the ancient cult of the Egyptians, who used this type of structure for sun-worship.”24 The astronomical features of the stones, while reportedly designed to aid the survivors of a future cataclysm, are, for many Elberton Christians, too reminiscent of the structures built by early pagans. Equally troubling to McQuaig is the monument’s overall resemblance to Stonehenge, as this suggests to him that it was designed for “occult worship of the Old Religion.”25

As the stones themselves refrain from making any religious statements, either pagan or otherwise, those who visit the Guidestones are left to speculate as to whether or not R. C. Christian would be pleased by the pagan rites that have taken place around his creation. For his part, Wyatt Martin continues to believe that the man he met did not have witchcraft in mind when he made his plans. “I know Mr. Christian to be an honorable man who holds a responsible position in his community, and [is] respected by those who know him.”26

While some in the community have continued to insist that there is more to the story of R. C. Christian than is officially told, others suspect that the entire account is fictional. The story is admittedly an odd one—after all, it is not every day that a mysterious stranger walks into a small town and commissions a monument to “Reason.” A few Elbertonians believe that it is extraordinary enough to be suspicious, and since before the first stone was quarried, rumors have circulated that the entire venture was merely a “promotional stunt”27 and that “the Guidestones were created by a cabal of local merchants and the granite producers to boost tourism and to erect a self-serving monument to the quarryman’s craft.”28

If it all truly was a hoax, though, it was certainly an elaborate and expensive one. Dozens of quarrymen and granite workers labored for months to produce the stones, and the services of United Nations translators, astronomers, and mathematicians had to be contracted in order to ensure the accuracy of the design details. And while the exact cost of the production of the Guidestones has never been disclosed, it was certainly more expensive than the average small business’ advertising campaign. Joe Fendley dismissed the theory with a laugh. “I’d think of a lot better ways to spend my money than this if I wanted to promote something.”29 Former member of the Elberton Granite Association, Hudson Cone, believes the same today. “They could’ve got a lot more bang for their buck using other more conventional marketing means,” he says.

And if the R. C. Christian story was really a myth, then it would have to be Fendley and Martin who concocted it. They were the two men who reportedly had contact with the mysterious benefactor, and they had the deepest involvement with the creation of the monument. But those who actually knew them did not find it likely that they would fabricate such a story.

“I know him well enough,” Wayne Mullenix said of Fendley, “so I don’t think that this is any real gimmick or hoax or that Joe’s behind it.”30 Even the granite man’s employees did not find the idea terribly plausible. “Big Joe’s too stingy,”31 one of the quarrymen at his Pyramid Quarry said, refuting the theory. And the popular sentiment about Martin was similarly inclined. His customers at the bank found him to be a dependable and honest man. “Wyatt is straight and plain business,” said one of the merchants with whom Martin regularly dealt. “He’s not your mystery monument type.”32

Hoax or no, the Georgia Guidestones have certainly been a boon to the granite industry and the area. Today it remains “the number one tourist attraction in Elbert County,” according to the current mayor of Elberton, Larry Guest. Indeed all who visit can see the fine craftsmanship of the many hands that worked the stone.

Wyatt Martin believes that the biggest reason that the townsfolk have been so reluctant to accept the Guidestones is that the man who commissioned them remained anonymous. “The fact that they didn’t know who put it there—that was the thing that was always the burr under their saddle,”33 he says with a chuckle. There is a generally held expectation, especially in a small town, that business transactions will be handled in a transparent and public fashion, with a handshake to seal the deal. But R. C. Christian never even spoke to most of the people who were involved in his project, and for some of the locals this seemed like suspect behavior.

The tract of land that the mysterious stranger purchased as a home for the Guidestones was a five-acre plot of the pasture of Wayne Mullenix’s family farm. Mullenix was among those who were put off by all the secrecy. “Selling my land to someone I never met and never will makes me wonder what’s going on,”34 he said. Those misgivings have remained in the hearts of some of the residents of Elbert County, though the Guidestones have stood for quite some time now. Some of the local preachers still deliver sermons about the “evil” landmark, and it gets very few visits from those in the local community.

But when the stones were vandalized in 2007, the community reacted strongly. Gary Jones, the current publisher of The Elberton Star, recalls that there was a “general feeling of disgust” from the locals at the idea that someone would try to destroy this piece of their history. The Elberton Sheriff’s Department even went so far as to install surveillance cameras at the site to deter any others who wish harm to the property. “Those stones have stood there for thirty years without disturbing anyone,” Jones says. “They are a good thing for the community.”

Because even though some people in town remain apprehensive about it, the monument does still have many supporters in Elberton. “The place has a personality all its own,” says Carolyn Cann, former weekly editor of The Elberton Star. “People are drawn there for a reason.”35 Cann has followed the Guidestones mystery since its beginnings, as she was the “ace reporter” for the coverage of the stones when they were built, according to Jones. And she has always believed that the words on the stones have a positive meaning. The man who sandblasted them into the granite agrees with her. “The sayings are all right,” says Charlie Clamp. “If mankind would go by the Guidestones, I think we’d have a better mankind.”36

The current mayor of Elberton, Joe Fendley’s successor, is less sure of what to make of the strange stones so near to his town. The messages engraved into the monument “seem a little strange,” says Mayor Larry Guest. “There’s some things on there most people wouldn’t agree with.” In truth, even those who do not subscribe to the conspiracy theories that speculate that the Guidestones portend that an evil global government is on the rise could find reasons to disagree with a few of the tenets. And in a politically conservative area like Elberton, Georgia, they could find more than just a few.

“I don’t know what those things are, and I don’t want to know.” A waitress at a local barbeque restaurant told a reporter on the day of the dedication. “The Russian’s on ’em so that when the Russians invade us they’ll have something to read.”37 As the structure was built during the Cold War, the inclusion of Russian in the languages into which the guides were translated was rather controversial at the time. The tenets’ call for peace and for the resolution of international disputes with diplomacy rather than warfare was also not well-received in some circles. But the Cold War was also a time when the threat of massive atomic destruction on a global scale loomed ominously every day.

“This is something that would survive in the event of a nuclear war,”38 countered George Gaines of the Elberton Granite Association at the unveiling ceremony. And if the Guidestones really were intended to stand as an aid to the survivors of that war, it would make sense for the guidelines it posited for civilization to have a more peaceful bent than the standard rhetoric of the day. “I think it is very great,” said Edgar Allen Davidson, a Jamaican quarryman who helped remove from the earth the chunks of granite that would become the Guidestones. “The monument will make a change in people’s lives. As days go by, people can see what the past days was.”39

These days though, with the Cold War over, thoughts of a potential nuclear Armageddon are generally far from the townsfolk’s minds. But the strange collection of stones remains, and with it its political sentiments. Many of the local residents do not agree with those ideas, and even Wyatt Martin himself has confessed to being somewhat put-off by the environmentalist sympathies expressed in the final tenet, “Be not a cancer on the Earth—Leave room for nature—Leave room for nature.”

The Mullenix family too has its doubts about the intentions of the creator of the monument, but they are still proud when they look out their windows in the morning and see it standing there. “I’m glad to see it for Elbert County,” says Wayne Mullenix’s wife, Mildred. She, like the rest of the world, does not know what the Guidestones really mean, but she knows that they have been good for the area.

It has been over thirty years now since that crowd of hundreds first gathered together in the Mullenix pasture to catch a glimpse of the mystery stones, and much of the local controversy has died down. “It’s become just another granite attraction,”40 says Tom Robinson, Joe Fendley’s successor as president of the Elberton Granite Finishing Company. Many of the attendees at the dedication ceremony have passed on now, and most of the rest have gone on to discussing other matters. “Interest in the Guidestones has waned in Elberton,” Hudson Cone admits. Events like the recent vandalism occasionally bring it back to the forefront of the townsfolk’s minds, but it is largely the outsiders now who passionately debate the meaning of the monument.

To the town of Elberton it now mainly means a quaint curiosity, and a source of income through the tourism it brings. “It means economic development for us,” says Mayor Guest, “more people in our hotels and restaurants.”

And for as long as its origins remain shrouded in secrecy and the unknown, it will likely remain the biggest reason for out-of-towners to visit the tiny city. Perhaps, as Mr. Christian hoped, it will remain an enigma forever. But there is also the chance that someday, someone will discover the answers to the questions that have been speculated upon for so long. “It’s a mystery, and I love a mystery,” says Carolyn Cann. “But I believe that sooner or later, the whole truth will come out.”41

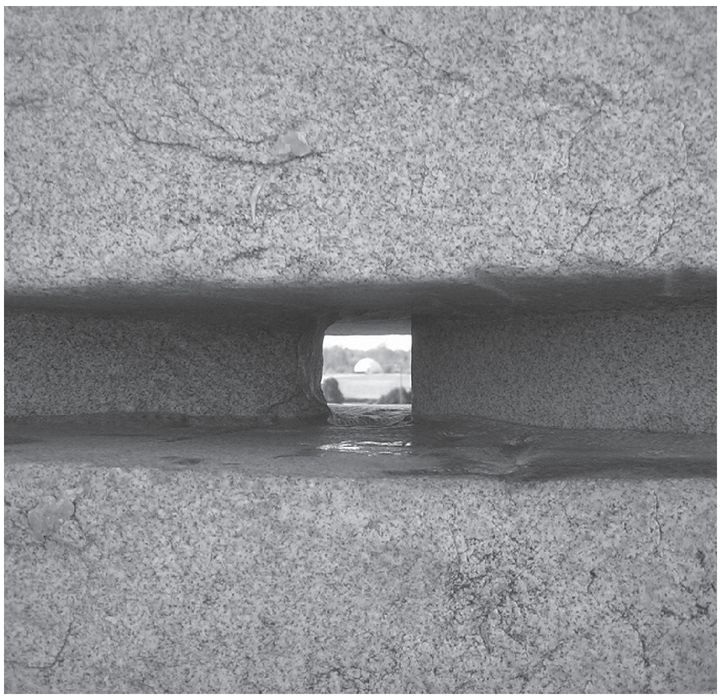

5. The “mail slot” marks the sunrise line on the winter and summer solstice

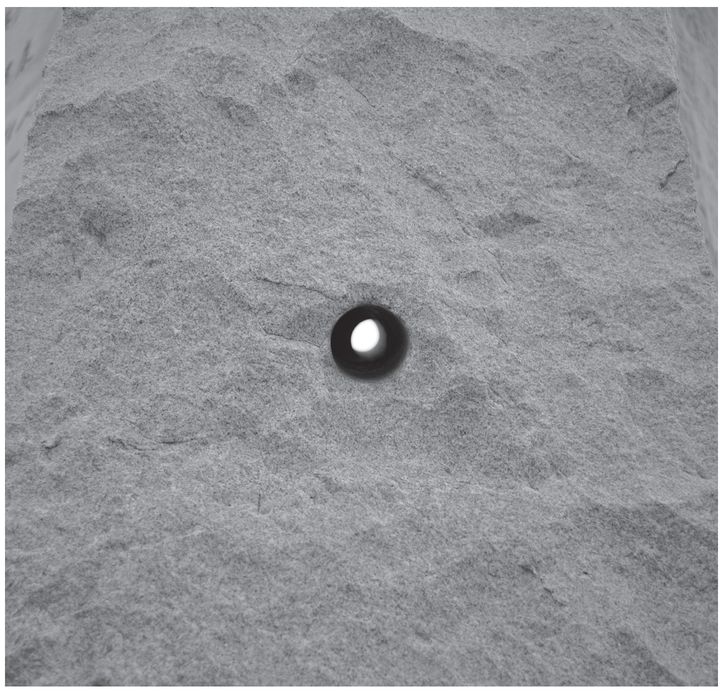

6. This shaft marks the position of Polaris throughout the year

7. A shaft cut through the capstone marks noontime throughout the year.