Much of the controversy that surrounds the Georgia Guidestones is centered around the speculations of various groups with regards to the authorial intent of the monument. Everyone familiar with the structure seems to have an opinion as to why its mysteriously anonymous creator commissioned it. This, however, is one question that is not left completely unanswered by R. C. Christian. The entire second chapter of Christian’s treatise, Common Sense Renewed, is devoted to answering it.

In that chapter Christian clearly enumerates the motivations that he claims caused him to take this particular action. Throughout the course of the remainder of the book, he outlines all of the political and social beliefs that he holds that give context to those motivations. Assuming that he did not deliberately dissemble to create a false impression of himself, this text uniquely resolves the matter of Christian’s purpose in erecting the Guidestones.

In “The Georgia Guidestones,” the second chapter of his book, Christian asserts the following:

I am the originator of the Georgia Guidestones and the sole author of its inscriptions. I have had the assistance of a number of other American citizens in bringing the monument into being. We have no mysterious purpose or ulterior motives. We seek common sense pathways to a peaceful world, without bias for particular creeds or philosophies … Stonehenge and other vestiges of ancient thought arouse our curiosity but carry no message for human guidance. The Guidestones have been erected to convey certain ideas across time to others. We hope that these silent stones and their inscriptions will merit a degree of approval and acceptance down the centuries, and by their silent persistence hasten in small ways the dawning of an age of reason.143

Explicitly, then, Christian’s purpose in commissioning the Georgia Guidestones was to promote a peaceful, sustainable society throughout the ages. He sought to do this by leaving behind a message, in the form of the ten precepts that are etched into the monument.

Those particular precepts, however, have been a source of contention throughout the whole of the Guidestones’ existence. They were phrased concisely so as to conform to the restrictions of space on the structure itself, but that same brevity makes them somewhat vague and open to a variety of interpretations. In Common Sense Renewed, Christian outlined his beliefs and ideas at greater length, thereby providing a much-needed tool for the understanding of Christian’s intentions.

The mystery of Robert Christian’s true identity has remained unsolved for thirty years. Wyatt Martin, the only man known to have the answer to the mystery, has kept his silence. Many people have put forth their speculations about the matter, but no hard evidence has ever emerged to implicate one particular individual. That said, careful as he was, Christian did leave some clues in his wake. They may never lead to a discovery of the enigmatic man’s real name, but they can help to engender an understanding of the sort of person that he was.

Only three people are known to have actually met the man who called himself “R. C. Christian” in person. He first introduced himself to the president of the Elberton Granite Finishing Company in 1979, Joe Fendley. From there, he made contact with the man who would become both his financial intermediary and something of a friend, Wyatt Martin, then president of the Granite City Bank. Joe Fendley has since passed away, and Wyatt Martin is now over eighty years old and in failing health. But Fendley also introduced Mr. Christian to another member of the Elberton Community, EGA member Hudson Cone. Fendley and Martin both recorded recollections of their encounters with the mysterious man in various places before it became too late for them to share what they knew with the world, and Cone remains alive and well enough to tell his part of the story. Only from these accounts is it possible to gain any knowledge of Christian’s appearance and demeanor.

In a pamphlet he published shortly after the monument was completed, Joe Fendley described the man who walked into his office to commission the Georgia Guidestones as simply “middle-aged” and “neatly dressed.”144 Financial intermediary Wyatt Martin was able to provide a little more detail, recalling that he was “probably about 5’ 11”. He had on a normal business suit with a tie. He wore a hat.”145 Martin also observed that he was “well-spoken, obviously an educated person.”146 In his own book, Common Sense Renewed, Robert Christian mentions that “for more than 60 years [he has] benefitted from the American political system.”147 From this last it can be reasonably extrapolated that at the time of the book’s first printing in 1986, the man was already more than sixty years old.

Hudson Cone’s recollections of Christian corroborate this. By his estimation, the strange man was in his “early seventies” when he met him. Cone laments the fact that he had only a brief and “hurried conversation” with Christian, but he did get a very good look at the man. He agreed that Christian was tall—though his own estimate was that he stood about “6’2” or 6’3”.” He noted also that he was quite thin, “not gaunt looking, but certainly thin,” and “bald-headed.” When he spoke, he had a midwestern American accent, as well. “I’ve been hunting up in Iowa,” Cone muses, “and I would say that he would definitely be from Iowa according to his accent.” If this is true, then it might explain why Christian chose a small Iowa publisher to produce his book. These little clues paint a physical portrait that is imperfect at best, but they do at least add to the greater sketch of Christian’s character.

About the life of the man, a little more can be determined. Christian was demonstrably a man of at least some means. Though Wyatt Martin has never chosen to reveal the exact sum of money that was paid out to Joe Fendley and his extensive crew for their labor and the cost of the granite, he has made it clear that it was substantial. And Fendley, when presented with the rumor that the figure was “in the neighborhood of fifty thousand dollars … said that that estimate was much too low.”148 In Fendley’s own recollections about the day he met Christian, he stated that he initially quoted the stranger an approximate price that was so high, he expected the man to balk then and there. No monument the size of the Georgia Guidestones had ever been created in Elbert County before, and special equipment had to be devised and implemented solely for the project. The price of such an undertaking was undoubtedly relatively high, and even if Christian did, as he said, have “the assistance of a number of other American citizens in bringing the monument into being,”149 a significant portion of the funds to support the project would likely have come from his own assets.

But his means were not unlimited. Hudson Cone recalls that Christian spoke at length about the outer ring of stones that were never placed around the Guidestones, which he referred to as the “moon stones.” Evidently, Christian and his organization had “run out of money” for that portion of the project, and at the time that Cone was speaking to him—shortly after the unveiling of the monument—they were actively petitioning environmentally-oriented nonprofit organizations to see if they could provide the funds. But as there remain no slabs of granite around the monument to mark the progression of the moon throughout the month, this attempt was apparently unsuccessful.

In March of 2010, it was revealed that Christian had a son. Wyatt Martin spoke to a journalist from CNN and informed him that he had been contacted by the son of R. C. Christian, who gave him the news that the mystery man had passed on.150 Martin has since commented that, while most people would not recognize the real name of Mr. Christian, “his son was probably a more notable, known person than he was.”151

We can also surmise that Christian traveled frequently and to diverse locations. Wyatt Martin, who was the only person with whom the mysterious man would communicate after his initial visits to Elberton, indicated in an interview with Wired magazine that “all of Mr. Christian’s correspondence came from different cities around the country. He never sent anything from the same place twice.”152 The financier also indicated that many of the places Christian visited were undeveloped and impoverished nations, such as Bangladesh. Martin felt that the man’s experiences in these countries had certainly contributed to his motivations in planning the Guidestones project, because such an educated man would have felt compelled to try to help resolve the issues that created so much human suffering.153

Wyatt Martin’s impression with regards to Christian’s level of education is supported by other evidence. The very structure of the Georgia Guidestones, which was very specifically mandated by Christian, tends to imply a broad range of experience in its author. The astrological features are strongly reminiscent of the historical British site of Stonehenge, a fact which Christian himself admitted to Martin was no coincidence. Christian told the banker that he had traveled to many famous landmarks, but that he was especially affected by his visit to Stonehenge. Reportedly, he also recited Henry James’ lines about the ancient monument to Martin: “You may put a hundred questions to these rough hewn giants as they bend in grim contemplation of their fallen companions; but your curiosity falls dead in the vast sunny stillness that enshrouds them.”154

James was not the only writer with whom Christian displayed a familiarity. The title of his own book is an allusion to Thomas Paine’s influential political treatise, Common Sense, and indeed the first chapter of Common Sense Renewed opens with a brief description of Paine’s life and ideas. Throughout the course of the book he also makes reference to the ideas of Gregor Mendel, Mark Twain, Isaac Newton, Charles Darwin, Albert Einstein, Karl Marx, Blaise Pascal, Galileo, and Socrates.

But even this evidence of his cultural literacy pales in comparison to the indication in his writings of his worldly awareness. He writes at length about the American political and economic systems, noting both their historical developments and their modern circumstances, but he does not confine himself to the discussion of domestic institutions alone. He also exhibits a remarkable knowledge of the governments and societies of several other nations, among them Russia, Japan, Sweden and China, referring to them frequently with both positive and negative comparisons to the United States.

Hudson Cone saw further evidence of the mysterious benefactor’s level of education, in his seemingly high degree of knowledge about plant-life. Cone hypothesized that the man may have been “some sort of naturalist” because during their conversation he frequently “called trees by their botanical names.” Christian also told Cone that he had recently visited the Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest near Robbinsville, North Carolina, to “see a certain kind of tree that grows up there and nowhere else.” If Christian was a botanist, or even simply a botanical enthusiast, that could account for the strong message of conservationism that is conveyed by the Guidestones.

Christian reveals another detail about himself in Common Sense Renewed. He discloses that some of his ancestors fought in the Revolutionary War, and that others fought on both sides of the American Civil War. According to Wyatt Martin, Christian himself had also been a military man for at least a time, as he served as a fighter pilot in World War II. If he was a career soldier and perhaps still a member of the armed forces when he commissioned the Guidestones in 1979, then this could be one potential explanation for his many travels.

All precise ideas regarding who the mysterious man was can only be speculation, however. The fact remains that too little concrete data is known of the man to allow a complete and specific picture of his life. But Robert Christian did leave behind an invaluable tool to aid the ongoing pursuit of an understanding of his character and motivations. The bulk of the book that he wrote and published in 1986 is devoted to the relation of Christian’s political, social, and philosophical ideas. Many of his proposals are now outdated or made irrelevant by the introduction of new information or infrastructure into human society in the time between the book’s publication and today. But though its utility as a potential resource for policymakers may have diminished, it remains quite pertinent to the discussion of the Georgia Guidestones and their author.

The chapters of Common Sense Renewed divide Christian’s ideas into several different rough categories: religion, domestic social problems, and foreign affairs—with specific regard to Cold War era politics and concerns. Each of these sections reveals a little more about the character of the man who wrote them, and when viewed together a more complete picture begins to emerge.

The tenth chapter of the book, entitled “Reflections on God and Religion,” summarizes his somewhat complex theological ideas. It is worth noting that when Christian described himself to Joe Fendley and Wyatt Martin, he said that he was “a follower of the teachings of Jesus Christ,”155 but, despite his pseudonym, he never actually referred to himself as a “Christian.” This may seem at first to be a semantic point, but viewed in the light of the more specific iterations of his belief structure that are outlined in “Reflections on God and Religion,” it appears to be an essential distinction.

Many of Robert Christian’s religious ideas fit well within the bounds of the modern sects of Christianity. He professes to believe in a single, benevolent God. He believes that two thousand years ago a man named Jesus performed miracles and influenced others with his faith and his philosophy, and that same man was put to death for his works. Yet Christian does not choose to self-identify as a member of any particular church. It is possible that this decision to eschew sectarian classifications was as a direct result of his stance on religious tolerance, as in his book he states that “it is apparent that no religion has a monopoly on truth,”156 and he encourages people of differing religious viewpoints to attempt to understand and accept one another.

In refusing to label himself with a specific spiritual viewpoint, he may have been attempting to emphasize his tolerant ideals, but it is also possible that he genuinely did not feel a kinship with any of the organized forms of Christianity. Some of R. C. Christian’s ideas seem to be at odds with the conventional standards held by most Christians. The various sects of Christianity interpret the Bible in different ways, but without exception they hold it to be the true and accurate Word of God. Christian, however, holds a more flexible view.

Appropriate humility suggests that we regard all our knowledge as incomplete and tentative, ever subject to revision in the light of new information.157

… our understanding of God is distorted and inadequate. We continue to use ancient concepts because of habit and because we lack good substitutes. Many wise people concede that God is almost completely unknowable for human minds and senses.158

In these passages Christian maintains that religious knowledge is subjective and malleable, implying that it is quite possible that many people, including himself, may prove to be incorrect in their assessments of the divine. This assertion, while couched in inoffensive terms, nevertheless stands in direct opposition to the viewpoints of the leaders of the various Judeo-Christian faiths and of other entities who consider themselves to be in possession of absolute truths.

Christian also indicates a dislike for religious dogma or ritual that he considers to be no longer relevant or appropriate in a modern setting. He highlights the fact that most of the major religions codified their ideas and rites at a time long past for a people and a culture long dead. The failure to update traditions to match the constantly evolving body of human knowledge has, he asserts, subjected religion in general to “criticism, and sometimes to ridicule.”159 In a sense, with this statement he speaks out against organized religion in general, as conservative traditionalism has been a fundamental quality of nearly all of the major world religions.

The overarching theme that pervades the entirety of Common Sense Renewed is the supremacy of human reason, and the chapter that discusses religion is no exception to this. In stark contrast to the standard doctrines of Christianity, which hold that faith is the final authority, Christian firmly asserts that emotional and intuitive reactions should only be considered after they have been examined by the intellect:

There is a legitimate place for inspired teachings by religious leaders who may through intuition or inspiration perceive concepts which lie beyond the reach of human reason and scientific proof. So long as those teachings do not conflict with our reasoned judgments and so long as they contribute to human happiness they can be accepted on faith.160

So long as we do not permit faith to override our rational powers we should use those talents to explore the frontiers which lie at the outer limits of scientific observation.161

This idea of using reason, not faith, as the touchstone for all other beliefs is much more reminiscent of the tenets of Deism than of any of the varieties of modern Christianity.

Though Deism has roots that go back as far as the ancient Greek philosophers, it was at the height of its popularity during the Enlightenment of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in Europe. Deists hold that the existence of a supreme being can be determined in a rational way by the application of reason, and that even that deity is subject to the natural laws of the universe. Christian echoes this idea at several points in his book:

Perhaps we are like cells in the mind of God, contributing to celestial functions beyond our ken, just as our cells unknowingly fashion our thoughts and actions. Perhaps the laws of nature order and constrain even the living and eternal Deity from which they spring, and of which they are a part.162

Judeo-Christian dogma commands belief in an omnipotent God who is not limited by laws of any kind. Christian’s writings, by contrast, are more consistent with Deistic beliefs on this matter.

R. C. Christian also connects himself with Deism by his many allusions to Thomas Paine and his works. As noted previously, the title of Christian’s book, Common Sense Renewed, is a clear reference to Paine’s seminal work, Common Sense. Christian also pulls a quotation from Paine’s The Rights of Man in his own chapter about human reproduction. And throughout Common Sense Renewed, Christian reiterates time and again that what he seeks to bring about is an “Age of Reason.”

In 1794, Thomas Paine published the first part of a three-part pamphlet entitled The Age of Reason. In this work, Paine outlined many of the common Deist arguments of the day in a bold and accessible style. Its effects on society at the time were huge and far-reaching. In subsequent years, other thinkers and authors latched on to the phrase, “the age of reason,” and began to use it to describe alternately the period of the Western Enlightenment and a theoretical future point in time in which human reason was the authority on which all decisions and plans were made. It is in this latter sense that Christian makes frequent use of the phrase.

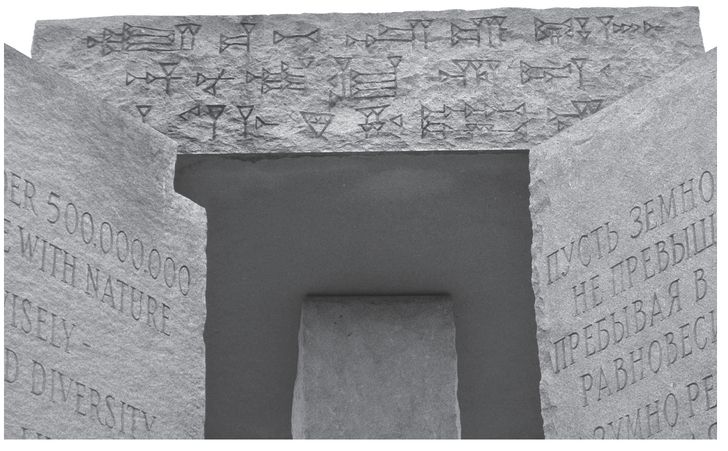

Along the four sides of the capstone of the Georgia Guidestones, in four ancient languages, the words “Let these be Guidestones to an Age of Reason” are engraved. In Christian’s book, he states that the Guidestones were meant to “hasten in small ways the dawning of an age of reason.”163 Chapters one, three, four, nine, and twelve of Common Sense Renewed all end with the words “Age of Reason,” and chapter eight is entitled “A Beginning for the Age of Reason.” Every single chapter employs the phrase at least once. And there are a variety of similarities in the content of Common Sense Renewed and The Age of Reason as well.

The motivations behind both treatises were born of parallel circumstances. At the beginning of “Reflections on God and Religion,” R. C. Christian mentions that in most of the communist nations of his time, atheism had become the state-mandated “religion.” The following chapter, “On the Conversion of Russia,” speaks at length about the ways in which the communist atheists could be persuaded to hold on to certain vestiges of spirituality. In order to do this, he asserts that it would be necessary to reevaluate the major religions of the world in a rational, reasoned light and to extract from them the basic core principles that they have in common. Those principles would then be presented as a universal code of human ethics.

At the beginning of The Age of Reason, Paine outlines his reason for the publication of his pamphlets.

The circumstance that has now taken place in France of the total abolition of the whole national order of priesthood, and of everything appertaining to compulsive systems of religion, and compulsive articles of faith, has not only precipitated my intention, but rendered a work of this kind exceedingly necessary, lest in the general wreck of superstition, of false systems of government, and false theology, we lose sight of morality, of humanity, and of the theology that is true.164

Disturbed by the effects that the French Revolution was having on the population’s general spirituality, Paine also felt the need to express his opinions on religion. He intended to show to the French that religious belief could be comprised of more than just the tradition and corruption that they perceived in the Catholic Church of the time, and that even religion could be dealt with rationally.

But it is not only Paine’s motivations that Christian echoes, but also some of his ideas. Christian saw problems with the established scriptures with respect to attempting to convert others because in their attempts to express truths clearly, they frequently used contradictory language.

Ancient writings which still play a prominent role in religions of the Judeo-Christian-Muslim tradition sometimes describe God as stern, righteous by human standards, vindictive, unforgiving and tyrannical. At other times God is represented as all-wise, loving, solicitous for our welfare, and forgiving of our failings. These conflicting interpretations reveal the inadequacy and confusion of our attempts to describe the true nature of the Supreme Being.165

Paine observed the same issues of inconsistency, though his language is much more hostile towards Christianity, and the conclusions that he reaches seem to differ somewhat from Christian’s:

Putting aside everything that might excite laughter by its absurdity, or detestation by its profaneness, and confining ourselves merely to an examination of the parts, it is impossible to conceive a story more derogatory to the Almighty, more inconsistent with his wisdom, more contradictory to his power, than [the Bible] is.166

At the time that Paine was writing, corruption and intolerance were still rampant problems within the body of the Church. His vehement, almost disgusted language with respect to Christianity is partially a reaction to these problems and partially a rhetorical device that he used in order to appeal to the common man. Christian obviously had fewer harsh feelings towards Christianity, and indeed embraced some elements of it, and thus chose a more affable tone for his criticisms.

Despite Paine’s seeming disrespect for Judeo-Christian thought, he, like most Deists of the time, shared Christian’s feelings on religious tolerance. In the dedicatory introduction of The Age of Reason, which he addressed to the citizens of the United States, Paine stated:

I put the following work under your protection. It contains my opinions upon Religion. You will do me the justice to remember, that I have always strenuously supported the Right of every Man to his own opinion, however different that opinion might be to mine. He who denies to another this right, makes a slave of himself to his present opinion, because he precludes himself the right of changing it.167

Open-minded ideas of this kind, while fairly commonplace in the modern West, were quite new and rare in Paine’s day. Irreverent and ostentatious though he may have been, Paine was undeniably an important figure of the Enlightenment, and he seems to have had a strong effect on Christian’s thoughts and work.

“Human intelligence,” Robert Christian felt, “is capable of devising solutions to all our problems—war, population control, justice under law, and the progressive improvement and perfection of our species as the shepherd of life on earth.”168 His intelligence led him to formulate courses of action that he felt could resolve all of those issues. He believed so fully in the potential power of his proposals that he committed them to paper in Common Sense Renewed and sent copies of his book to thousands of political leaders the world over at his own expense.

Ideas that a person holds so dearly that he is willing to act on them, even when doing so is inconvenient and comes at great personal cost, are almost certain to be integral to that person’s sense of self. So while a person’s political stance does not always necessarily reveal much about his character, in Christian’s case his beliefs on social and cultural change can be used to dissipate some of the fog of mystery that surrounds his identity.

Based upon the platform that he outlines in his book, we can infer that, if R. C. Christian were still alive today, he would most likely vote like a Republican with strong libertarian leanings. Most of the plans that he lays out to combat America’s ills are very much in keeping with a strictly conservative domestic policy. In general, he adopts the stance that the major ills facing the United States have their roots in “too much government”169 and the naiveté of politicians who fail to see that the persistence of a large national debt will eventually put the country at a severe global disadvantage.

Many of his ideas and complaints are familiar to any modern American who has recently tuned in to Fox News. He scorns the lack of stricture with which the U.S. polices its borders. He calls for stronger sanctions on employers who knowingly provide jobs to illegal immigrants, and suggests that “idle but able-bodied Americans”170 ought to perform those jobs, even if they consider them to be “below their social station, or … esthetically distasteful.”171 He condemns the removal of all traces of religion and spirituality from public schools and enjoins districts to introduce a generalized code of moral conduct into the perceived ethical vacuum in the educational system.

Christian calls for the abolition of the minimum wage and of labor regulations that “hamper our productive efforts.”172 He laments the many other laws that dictate the internal policies of corporate entities, saying that though they are well-meaning, they “are a direct cause for increased costs,”173 which in turn impedes America’s ability to remain globally competitive. He speaks longingly of a time when “‘profit’ was not a nasty word.”174 A substantial portion of the text dealing with socio-economic issues is focused on commercial regulations.

Mixed in with his run-of-the-mill socially conservative ideas, however, are some suggestions that are a good bit more unusual. He proposes that universities and technical colleges restrict the enrollment of students in various areas of concentration based upon projections of actual need for careers in their related fields. He advises the creation of a nationally-funded railway network in order to provide incentives for distributors to do more of their shipping across rails instead of the highways, thereby relieving congestion and stress on roads and easing some of the energy burden away from petroleum and onto coal. He recommends the creation and implementation of a new, worldwide language to aid both trade and peaceful relations.

Most noteworthy, however, are Christian’s proposals challenging some of our society’s standard ideas of personal freedom. His suggestion that unemployment benefits be eliminated is, by itself, not far out of the ordinary. But Christian goes one step further, stating that unemployed individuals should be forced to relocate to areas of higher employment availability within the country, regardless of the distance involved. “An illiterate Mexican or Jamaican citizen will travel thousands of miles eagerly to seek … employment,” he asserts; “unemployed Americans should be required to make similar efforts.” 175 Such a scenario would certainly ruffle many feathers if implemented, but Christian counters that “Americans have grown accustomed to the comfortable living standards based upon our once abundant resources. We are inclined to take them for granted.”176 This then, he hoped, would perhaps engender more of an appreciation for that standard of living.

Even more unconventional is his position on healthcare. In a very brief section of the text, Christian discusses the problems of the rising costs of medical procedures and concludes that it will be necessary to limit the amount of care that is distributed.

We simply cannot afford to replace every failing heart with a pump or transplant … It will be necessary for well informed citizens to work with knowledgeable physicians in establishing guidelines that will make possible a reasonable allocation or “rationing” of the care that we can collectively afford, favoring those individuals whose continuing lives are most valuable to society at large.177

It is the last part of his assessment that would likely be most controversial. In recent years, discussions about how healthcare should be monitored or managed in America have shown that many people have very strong feelings on the subject. Undoubtedly, this was true during Christian’s time as well, but the anonymous man did not compromise his approach of using reason to determine policy merely to avoid controversy at any point in his book, and this was no exception.

Many of Christian’s ideas for the improvement of the social and economic structures of the United States are unconventional, but they are nevertheless quite interesting. The most original of these proposals seem to indicate, if nothing else, that he was a man who spent a lot of time thinking about the problems that plagued his society, and that he could not have contented himself until he made an attempt to foster constructive changes in the system that produced those problems. The Guidestones were a part of that attempt, and Common Sense Renewed was another. Any further steps he may have taken were not associated with the same pseudonym, so it is impossible to know what they may have been.

Very little is presently known about the identity of the man who erected the Guidestones. Indeed it is quite possible that further biographical information will never surface to shed light on his motivations. But his identity is only part of the story. The context and circumstances of the time in which he lived also heavily influenced Christian’s decision to create the Guidestones. About that time period there is substantially more information.

13. Structural damage to English face (top right corner)—evidence of an apparent attempt to topple the monument