It is the summer of 1979.

It has been thirty-four years since the world first bore witness to the devastating effects of nuclear weaponry. Between 150,000 and 246,000 people perished in the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.178 Though the exact details of the events were hidden from the public eye for many years, it is now widely known that the atomic bombs visited horrors upon the people of those cities, the like of which had never been seen before. It is also widely known that the global stockpile of nuclear weapons is both much more numerous and much more powerful now than it was in 1945.

It has been twenty-three years since the Soviet premier, Nikita Khrushchev, told the ambassadors of Western capitalist countries, “We will bury you!”179 in a shocking alleged slip of the tongue that nevertheless chilled all who heard it. The USSR has made it abundantly clear that they have little to no use for non-communist nations, and that they have the military might to, at least on occasion, silence them.

It has been seventeen years since the brinksmanship of the Cuban Missile Crisis nearly triggered a thermonuclear war, and that danger is still a possibility. After a few hopeful years of détente, relations between the United States and the Soviet Union are becoming strained once again as Soviet-backed communist uprisings in other countries threaten to tip the shaky balance of control between the rival superpowers.

It has been just over a year since the Afghan people executed Mohammad Daoud Khan, who had been their president, and replaced him with a member of their communist party. In six months the Soviet Army will invade Afghanistan to solidify the newly reformed government, triggering intense fear and unease in the West in the process.

It is the summer of 1979, and for three decades the West has lived with the uneasy knowledge that the Soviet Union has “The Bomb.”

In America today it is nearly impossible for even those who were adults during the Cold War to fully remember the specter of dread that pervaded the era. Today, fallout shelters are kitschy curiosities, and instructional films like Duck and Cover are subjects of fun. Movies and books that depict wars with Russia are viewed with nostalgia or sometimes even amusement. The threat appears to have passed. The Berlin Wall has fallen, the Soviet Union has disbanded, and the United States Department of Defense has turned its eyes to other matters.

Since the events of September 11, 2001, the watchword has been “terrorism,” and many Americans are preoccupied with fears that other small groups of fanatics will detonate explosives in other crowded areas. These fears are real, and their effects are felt in modern society, but they are of a different species than the fears felt by society between 1949 and 1989. Because the worry in those days was not that a few thousand people would be murdered by a madman, but that perhaps the entire population of the world would be decimated in a crossfire of nuclear missiles. For many people, this was not merely a possibility, but an inevitability.

For R. C. Christian as for other politically conscious people of the time, the prospect of a full-scale nuclear war seemed more and more likely. The arms race engendered by the doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction had resulted in an unprecedented build-up of weapons in both the USSR and the United States. In 1949, there were only 246 nuclear warheads worldwide, but by 1979, there were 24,107 missiles in the U.S. stockpile and nearly 28,000 in the USSR. France, China and the United Kingdom each possessed modest nuclear arsenals by that point as well, bringing the global total to well over 50,000 atomic warheads.180 Many of these bombs were actively deployed at all times, shuttling back and forth from their fail-safe points, waiting for the moment they were ordered to drop their payloads.

The idea that the Cold War could somehow reach a peaceful resolution without any bloodshed seemed increasingly naïve. Neither side was showing any signs of backing away from the hostilities. The conflict escalated tirelessly, and it seemed as though nuclear war would one day be unavoidable.

Robert Christian was a worldly man who was not only aware of current events, but also felt the need to act upon them. When faced with danger, it is only natural for a person to take measures to protect himself, but Christian evidently felt that he had a stake in not only his own well-being but that of mankind in general. So while he probably built a fallout shelter for himself and his family in his backyard, he also took steps to attempt to build a fallout shelter for civilization itself.

He built a monument that he intended would “convey certain ideas across time to others.”181 In the years since the monument was built, many people have disagreed with those ideas, but Christian believed that their implementation could lead to a better, more peaceful and balanced civilization in the future. To clarify and disseminate his ideas, he wrote a book and distributed it to thousands of political leaders the world over in the hopes that they could take the steps required to avert a nuclear holocaust. But should the worst occur, the Georgia Guidestones, strategically located “away from the main tourist centers” and in a “generally mild climate,”182 would likely endure the catastrophe and live on to advise future generations on how to avoid the mistakes of their predecessors.

Christian believed war had become a barbaric anachronism that had no place in modern society. He lamented that man’s great capacity for reason had not been exercised in this area:

We live in a time of great peril. Humanity and the proud achievements of its infancy on earth are in grave danger. Our knowledge has outstripped wisdom … We have advanced our knowledge of the natural sciences but have not adequately controlled our baser animal instincts. We have begun to accept the rule of law but have limited its application, permitting it to regulate the affairs of individuals and of small political divisions while we neglect to use it in controlling major aggression. We have outlawed the use of murder and violence in resolving individual disputes, but have failed to develop procedures to peacefully settle conflicts between nations.183

Many of his ideas for developing a better global society centered around this core theme of eschewing violence in favor of reasoned discussion.

The sixth tenet etched into the Guidestones, “Let all nations rule internally, resolving external disputes in a world court,” addresses this explicitly. It was Christian’s belief that the development of an international institution specifically designed to enable nations to resolve their disputes and handle their grievances with one another through mediated discussion could eliminate the need for war. Certain simple, generalized global laws would dictate the conduct of the countries of the Earth, and this court would enforce them. The result, he hoped, would be something similar to the original intentions behind the United Nations, but that would be unhampered by the diplomatic restrictions and unchecked veto powers that obstruct the UN’s effectiveness.

The main barriers, as Christian saw it, to the creation of such an institution were the seemingly irreconcilable differences between capitalist and communist social and judicial systems. Russian communism, he felt, allowed too much power to be in the hands of too few people and was not responsive enough to the needs of the populace at large. He also asserted, however, that some of the criticisms of American capitalism were valid, and that certain checks needed to be applied to the system to prevent abuses. While he did not expect either the Soviet Union or the United States to make any fundamental changes to their respective political systems, he felt that they might be motivated to come to some compromises, as “thinking people in both nations must soon realize the futility of continuing the ‘cold war’ and its attendant arms race.”184

Christian primarily outlines his ideas for these compromises in two of the chapters in Common Sense Renewed, “A Beginning for the Age of Reason” and “To Make Partners of Rivals.” As an opening conciliatory gesture, he recommends that the future home of the “World Congress of Reason” be situated in Russia, so as to balance the fact that the United Nations is headquartered in New York. But he goes on to indicate that the Soviets must separate themselves from the core objective of converting all of the countries of the world to communist political systems, by force if necessary. This goal, he says, prohibits the United States from being able to trust the Soviets not to attempt to sow dissent within its own boundaries, and thereby prohibits peace.

He also recommends that the Soviets inject a small element of democracy into their present system, allowing members of certain collectives or workers at factories to elect representatives who would then become party members. He then suggests that the party members would vote to select the nominees that were then put forward on the unopposed ballots to the people. This, he asserts, would allow the public some measure of voice in the policies that shape their lives without disrupting the general tone and structure of the political system in the USSR. Controversially, Christian even suggests that this or another system of limited suffrage might prove to be better than the American democratic system, which he feels is sometimes disrupted by unintelligent or uninformed voters:

A “selective democracy” sustained through suffrage standards of a high order, using the mechanism of the Communist Party may ultimately prove to be a superior form of government. If political power is transmitted from the people to those in ruling positions in a manner which reflects knowledge and understanding by those who participate in elections, government of the people by the best representatives of the people may become a reality.185

The same criticisms of American democracy are expanded upon in his chapter “Suffrage in the United States,” where Christian asserts that a person should be required to provide both “proof of understanding of our government and its history” and “evidence of economic productivity”186 in order to earn his vote.

Christian perceived other flaws in the American system as well, however. He alleged that one byproduct of capitalism, inherited wealth, was an exceedingly great threat to effectual democracy, comparing the situation it creates to that of an aristocracy. “There is merit,” he asserts, “in permitting enterprising individuals to enjoy the fruits of their labor throughout their lives. It is more difficult to justify the transferral of that wealth to others who have not contributed in any way to its creation.”187 To resolve this problem, Christian suggests that, upon their deaths, exceedingly wealthy people only be allowed to leave behind modest sums to support any surviving spouses or children, and that the rest of their wealth be confiscated or reinvested by the state. He felt that this would remove the threat of an entrenched, powerful upper-class and increase economic mobility in America.

Other, more minor proposals are put forward to the Soviets and Americans for ways to make their respective systems of government more harmonious with one another, but Christian stresses that there is really only one thing that the two nations need agree on in order to make his system work:

Leaders in both countries should jointly develop an international philosophy whereby a variety of political and economic systems can coexist in friendly competition … Political patterns will undergo endless change in the future. We should not attempt to fit all nations to one pattern. No system is suited to all future time. If America and the Soviet Union will agree on this basic premise, together they can lead the world in a new, nonviolent, revolution that will make reason and compassion the guiding forces of humanity.188

Many of the ideas that Robert Christian puts forth with respect to Soviet-American relations are no longer relevant in the post-Cold-War world. The Soviet Union has collapsed, and communism of the type that was practiced within its borders is seldom found in the world today. But these chapters of his book are far from useless for one who is searching for Christian’s purpose in creating the Georgia Guidestones—they are essential.

From these pages it is abundantly clear that this anonymous man’s mind was much preoccupied with world affairs during this period. He composed an entire book detailing his thoughts on how to resolve the crisis of the Cold War, and his chapter on the creation of the Guidestones is seamlessly a part of it. Christian’s opinion of the military struggles of nations is inexorably tied to his motivation in commissioning the monument. “His thoughts,” Wyatt Martin claims, “were that [the Guidestones] would more or less help people to reestablish … civilization if we became stupid enough to annihilate each other with atomic weapons.”189

The people who have visited the Guidestones in their humble setting in the time since the Cold War ended have often walked away from the landmark confused. Without the historical context in which they were conceived, the stones tell an incomplete story, and it is difficult for a person in current times to understand what could possibly motivate a man to anonymously erect a monument engraved with guidelines for the conduct of nations. Many of them have supposed sinister ulterior motives in the absence of any apparent evidence of intent.

But from the writings he left behind, it seems clear that the mysterious R. C. Christian was just a man frightened for his world. He watched events unfold around him that were dangerous to all of mankind, events that he was powerless to control, and he felt the need to do something to advance the ideas that he felt might make things right. Those ideas are themselves in many cases controversial, but whatever their actual merits, Christian at least seemed to genuinely believe that they would improve the state of mankind.

Whatever his name, he was a man, and his intentions were good. He acted upon his conscience and undertook a project that was massive in both scale and cost, all in the name of trying to create a better world. His opinions on that better world still stand on a hill looking down on Elberton, Georgia, with the contrary opinions of others scrawled across them in paint and epoxy. The merits of those differing opinions are not quantifiable, but the mediums of their expression seem to differ vastly in quality.

But perhaps the next visitor to the Guidestones who disagrees with the message he sees will be inspired, not to inhibit the expression of Christian’s ideas about how to better mankind, but to express his own publicly as well. And perhaps through the open and constructive discourse of such lofty thoughts we can indeed find the pathway to a better world.

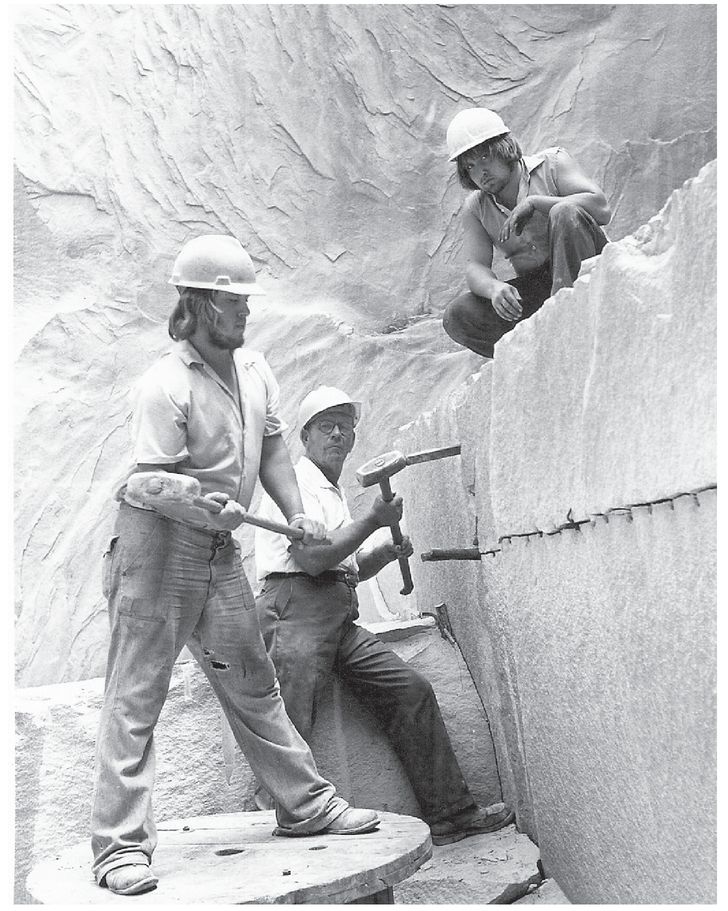

14. Workers at the Pyramid Quarry extracting granite blocks for the Guidestones project