The first day of a fresh army recruit started with waiting and idleness. From half past eight in the morning until three in the afternoon, the new conscripts bided their time in an exercise of obedience and patience. At last Tony Fokker was assigned to the ninth company of the Second Regiment of Fortress Artillery at Naarden, about fifteen miles southeast of Amsterdam. The journey from Haarlem to the Naarden-Bussem rail station was by train. From there the fortress was half an hour’s march. Tony used the opportunity to get on a friendly footing with his sergeant by offering him a handful of expensive cigars that he had brought on purpose—to which the sergeant proved “most susceptible,” Tony wrote in a letter to his mother.1 Once in Naarden, the recruits were fed first. After that the troops were aligned in the parade ground in front of the Promers barracks and addressed by the commanding officer. Then they were dismissed to the quartermaster, where everyone was issued the customary dark blue tunics, white pants, blue cap, and dark greatcoat of the fortress artillery. A short-sticked shovel and a handful of personal items completed the gear. Tony found his fork, spoon, and mess tin all equally greasy and dirty. Only the food itself—potatoes with beans and meat—proved passable and even “most edible.”2

The barracks themselves gave Tony a shock. The Naarden fortress, inhabited by 630 soldiers and a hundred officers and situated under more than eight feet of earth, represented a completely foreign, hectic world. Once past the gate with its fierce-looking lions that held the royal coat of arms, “Je maintiendrai,” a long, dark vaulted corridor led away from civilian existence. In the bomb-free brick passageway every footstep echoed. The corridor divided the complex in two. There was a cold draft. Here privacy did not exist. Tony was given one of the fifty-six low wooden sleeping bunks in one of the barracks’ six dormitory caverns, and introduced to his “sleeping mate” on the bed next to his. As a mere soldier, his own private space was no larger than a section of planking attached to the wall at the far end of the dormitory—and the “rock hard straw bag” that formed his bed.3 In the middle of the dormitories, bare wooden soldiers’ tables stood, with planks to sit on attached to the legs. Chairs were provided only in the sick bay. There was a single, stinking communal toilet and wash facility for the whole garrison. Only the officers had better accommodations, meaning they had their own chairs to sit on.

Tony found these circumstances very difficult. He longed for home. Discouraged by the spartan conditions, he tried to file for a medical discharge that same day. But in “the small cubicle all the way in the back in the dark” of the sick bay, where the military physician examined him, his “skewed leg” was given no attention whatsoever.4 The doctor barely listened to his complaint of having uneven legs. Undeterred, Tony inquired about the opportunity to have a second examination later that week. His request was summarily dismissed. A soldier’s existence was proving to be nothing like the protected civilian life in Haarlem that he had just left.

Haarlem, twelve miles west of Amsterdam, was a city beloved by returning colonials. Since their arrival in 1894 it had been the residence of the Fokkers. In June of that year, Herman, Anna, Toos, and Tony had finally set foot in Holland after a sea voyage of about five weeks from Batavia. With the years of hard work in the tropics behind him, Herman Fokker now found time for his cigar, good company, and a game of billiards. But for the children Haarlem was a strange, cold world they did not know and did not understand. For Tony the move meant “leaving everything behind.”5 He and Toos had trouble feeling themselves at home in their new surroundings. The children acted withdrawn and behaved shyly.

In many respects the Dutch city on the Spaarne River was the opposite of Njoenjoer and Wlingi. Its streets were paved and narrow, and its high stone houses made Tony and Toos feel small. Only the trees and the grass of the Haarlemmerhout park, on the outskirts of the city, reminded them of Java’s lush greenery. Luckily, the Fokkers passed their first summer in a hotel along the Haarlemmerhout, because the house that Herman had bought was not yet ready when they first arrived.6 The Hotel Widow van den Berg was the final stop of the horse-drawn tram from the station. It had been built in 1889 at the most beautiful spot in the park, with a big fountain in front and overlooking a deer pen. Widow van den Berg also had modern amenities such as private balconies for each room. For that reason it was especially popular among summer guests.7

The quiet environment of the Haarlemmerhout helped the children adjust. Then, on August 1, Herman registered himself and his family as the new residents of Kleine Houtweg number 41 (now 65), just outside the city center.8 Number 41, a typical Dutch townhouse of the period, had few features that stood out. It was about twenty-five feet wide and forty feet deep, located on the edge of the old town. Initially it had been designed as a somewhat stately town mansion, but in the course of construction it had been divided into two residences that essentially mirrored each other. It overlooked the Frederiks Park, a view of which Herman soon became fond.

For little Tony, moving to Haarlem was not easy. In contrast to the house on Njoenjoer, where the inside and outside interlaced and where the children had their own foal that moved in and out of the house like the dog did, the doors at Kleine Houtweg were usually closed. The building did not even have a front yard. Visitors were shown straight into a small vestibule that doubled as a hallway, or into the adjacent antechamber. A door with decorated glass panes gave access from the vestibule to a narrow corridor that split the house in two. The left side held the antechamber, the basement entrance, and the kitchen and pantry, primarily intended for the small house staff. On the right side of the corridor was the living room, with en suite dining. From there double doors led to a hundred-foot-deep garden where the children could play with the sheepdog Max. Between the hallway and the dining room was a niche containing a toilet and built-in stairs that led to the second floor. At the top one entered a small, somewhat dark landing that gave access to three bedrooms, a guest room, a bathroom, and—luxurious for the time—a second toilet. Behind a closed door on the landing a second staircase led to the attic. The attic’s rear included three small bedrooms for the kitchen help and two maids. Their chambers were separated by a walkway from the spacious storage room in the front.9 For a modest-sized family such as the Fokkers it was a large house, equipped with such modern conveniences as a bathroom with running water. Yet none of this appealed to little Tony. He later remembered the house and garden as constricted. The Dutch climate did not help. For the first time in their lives, the children had the strange experience of snow.

What Haarlem had in abundance was water. A mere 650 feet from the house was the canal that separated the old city from the new expansion where the Fokkers lived. On the quays at the weigh house and along the Spaarne River, ships moored daily to load and unload. Few were seagoing vessels; most ships were inland barges and other freight carrying vessels rigged with sails. But for young Tony, water and ships exerted an irresistible attraction.

The same could not be said of school. At the nearby elementary school Tony proved himself a mediocre student. In his own words, “School and I didn’t agree at all. Active, high-spirited, full of inventive ideas with a practical turn to them, I found study a boring routine, monotonous in the extreme, something which the teachers did little to make more interesting. Herman Fokker’s little boy, Tony, soon became a byword and a hissing to the irritated pedagogues….It has since seemed to me that most of the teachers showed a lack of imagination and of any real teaching ability when they attempted to force a square peg into a round hole.”10 Despite his ingenious methods for spying, about which he boasted in his autobiography, he invariably ended at the bottom of his class, yet only had one year in which he was not promoted to the next grade.

At home the storage room in the attic was Tony’s preferred spot. Here he built his own little world, which gradually took shape from all sorts of loose objects that he gathered. He was a creative child, with a special gift for tinkering. Before long the floor of the attic was filled with miniature rail tracks constructed from tiny strips of metal. He ran self-built toy trains on these with his friends, and later undertook experiments with electricity, miniature steam engines, and Bunsen burners that ran on gas he illegally tapped from a pipe that ran to their neighbors’ house. Tony also showed prospects as a tradesman; his mother preserved an early “bill” from the “Electro-Technical Bureau Fokker & Co.” for the total amount of 40 cents, charged for soldering caps on some lead piping.11 The water also beckoned, although his father refused to buy him the small boat he longed for. Undaunted, at twelve years of age Tony managed to build his own small canoe in the attic storage room. Herman Fokker, who encouraged his son’s tinkering activities from time to time, was sufficiently impressed to have the canoe hoisted out the attic window and brought to a nearby wharf to seal the vessel’s planks and have it painted.

No matter how much agony Tony suffered in primary school, his years of secondary education proved worse. In the summer of 1903 his father registered him at the municipal Higher Civilian School (HBS), which offered a five-year program. The school had a good reputation, and Tony had to pass an exam to get in. To the relief of his parents, he was accepted. From September 1903 until December 1908 a good part of his life took place within the high walls of this institution. The school was located on a square just behind Haarlem’s city hall, a mere ten minutes’ walk from Tony’s house. It was an imposing building, with hollow-sounding corridors and classrooms high enough to enable an amphitheater arrangement in the biology and the physics rooms so that pupils had a better view of demonstrations and tests. Since the school’s founding in 1864, the number of pupils had risen considerably. When Tony began classes, about two hundred students were enrolled, which resulted in a lack of space and classrooms. To address the problem several adjacent houses were added to the school building, creating further organizational discomforts. Some classes, such as drawing and arts, were taught in former living rooms, garden rooms, bedrooms, and the like that could be reached only through a maze of passageways and stairs that were never built for the number of persons using them. Such classes seemed at the end of the world, as a former pupil later remarked. Eventually a second school building was opened in a nearby converted gas factory in September 1907. But overall the facilities remained substandard throughout.

Tony Fokker was an unmotivated student, and his results showed it. Although he was conditionally promoted after his first year, he ended that year failing in no less than six subjects: geography, history, Dutch, German, French, and even draftsmanship.12 The school principal, Hotse Brongersma, resolved to sit him in the first bench in every class so that his teachers would be able to keep an eye on him. More often than teachers later cared to remember, he was disciplined because of pranks and even suspended for several days—which was much to Tony’s liking as it provided him with extra time to spend on his various hobbies.13 There was nothing he liked better than playing hooky, and he was seldom in search of excuses to do so, honoring the adage high on the wall in his biology class: “Knowledge means much. Character means more.” In a commemorative issue of the school paper, published on the occasion of the school’s sixtieth anniversary, he recounted how he would hide out until the concierge was back from his rounds to report absentees; then Tony would reappear, panting and pretending to be out of breath, his hands oily from the chain of his bicycle that had supposedly broken, begging to be stricken from the absentee list and allowed to rejoin his class. If the concierge allowed this, Tony would quietly escape to spend his day on the Spaarne River.14 More than once he had to report to “the boss,” Brongersma—an “old and grey gentleman” who ruled the school with dignity.15 Once Brongersma summoned him on the customary free Wednesday afternoon; Tony daringly protested “that I didn’t understand why the headmaster would sacrifice his own free afternoon to rob me of mine, thus punishing himself without having committed any wrongdoing, which I found completely illogical…an argument that he found so right that he released me on the spot.”16 Such occasions were, of course, exceptional. He would have to repeat his fourth year as well, after showing a report card with no less than ten subjects in which he had failed. In his autobiography he noted, “History and languages—I couldn’t have cared less. Speech practice I found gruesome.”17

In the end gymnastics was the only subject in which Tony demonstrated real talent. For geometry and physics his grades were passable, but only just. Yet in algebra, chemistry, mechanics, history, and modern languages he came nowhere near passing.18 Pranks were more his thing: stink bombs, shooting pellets. As results did not improve, father and son Fokker threw in the towel at Christmas 1908, at the end of a disastrous first semester of his second year in the fourth grade (the equivalent of an American student’s freshman year).19

Tony was glad to close the school doors behind him. As he put it, “I’ve learned all that I can.”20 Instead he focused on his big hobby, water sports: rowing his skiff, sailing his small dory class sailboat, which required great concentration to avoid capsizing. For his boundless enthusiasm he had already been elected second commissioner of Haarlem’s Rowing and Sailing Club at the annual meeting on February 22, 1908. Contemporaries called him a daring sailor. At the Amsterdam dory races “Fokkie,” as he was fondly called at the club, won several prizes.21 Water was his big passion, and there was no risk he would not dare to prove it. Once he connected a long plank to the roof of the boathouse and laughingly rode his bicycle over it into the Spaarne. Spectators cheered as he reemerged and swam ashore with his bike in hand.22

On dry land the attic remained his domain. Here he pondered various experiments and in the process developed a new interest: aviation. In 1909 aviation was still a new phenomenon that was conquering Europe rapidly. Spectators flocked by the hundreds of thousands to spectacular air meets, even if they had to travel for days to get there. The newspapers were full of the latest events and achievements. On June 27 the very first airplane took off from Dutch soil. Boys dreamed of an exciting career as an aviator. Soon Tony was among those who wished to learn all about flight. Technical knowledge about aviation, however, then existed only in the heads of less than a thousand people worldwide, and it remained inaccessible to a nineteen-year-old school dropout without qualifications. Yet Tony paired a creative mind with a keenness that was way above average, working with what information that did reach him to expand his understanding of the phenomenon of flight. He tried to gain some firsthand knowledge of aerodynamics. From celluloid he cut small basic airplane-shaped models and launched them from the attic window. He constructed representations of the steering mechanisms of planes that he had read about and had seen photographs of in newspapers.23

He also embarked on an engineering adventure with his friend and classmate Frits Cremer, another unruly spirit who shared a history of bad behavior and came from an affluent family.24 Herman Fokker’s means, however, could hardly compare to those of Jacob Cremer, Frits’s father, who had been chairman of the board of the NHM and of the Deli Company, which traded in colonial goods such as tin, tobacco, and other commodities, and who had also been the nation’s Minister for Colonial Affairs. The Cremers lived in an enormous mansion on their private estate outside Haarlem, Duin en Kruidberg. Jacob had the house and grounds specially built and furnished to meet his every demand as a millionaire.

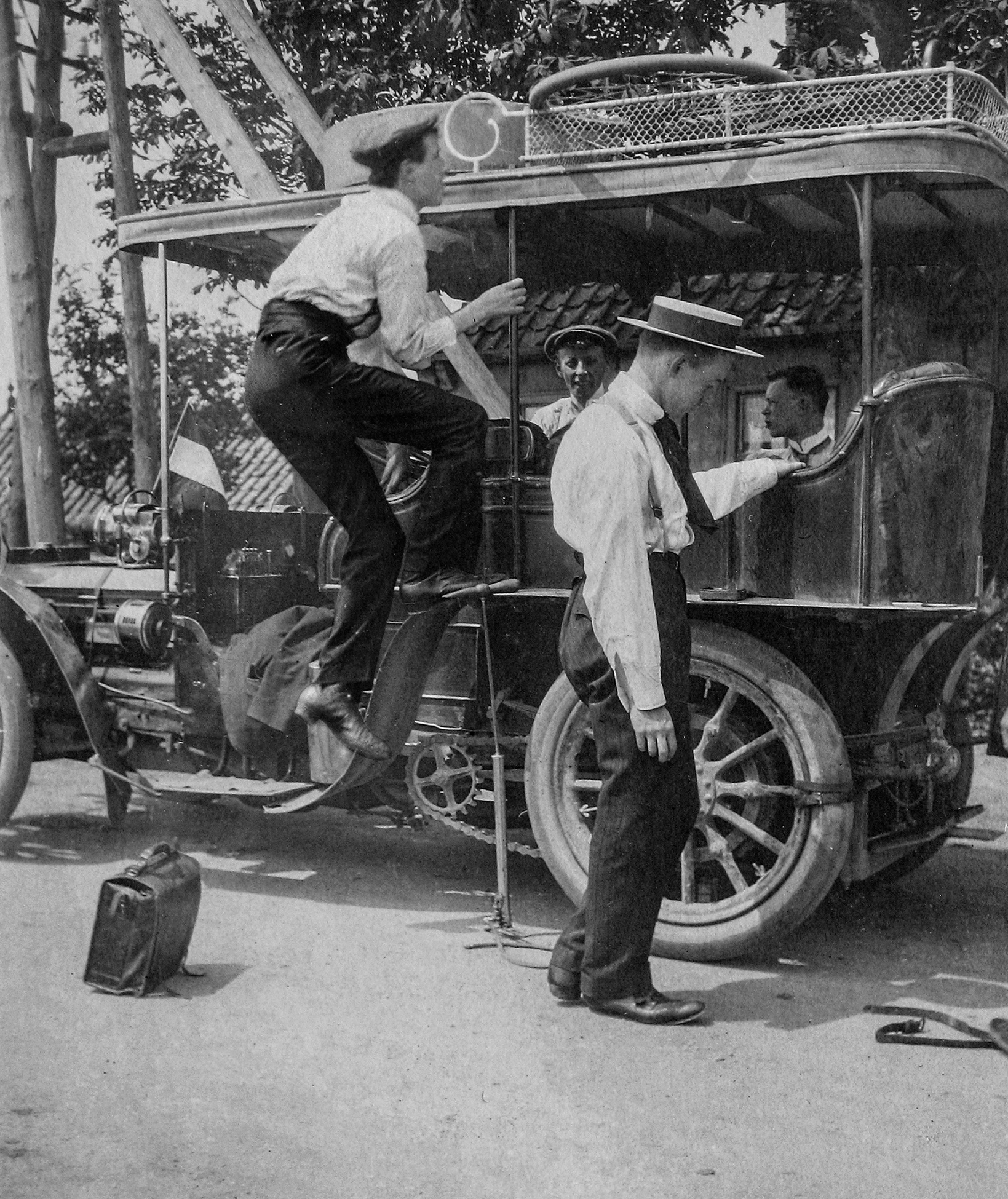

It was there that the two young friends embarked upon the development of an idea that had been in the back of Tony’s mind for some time: a car tire that would minimize the risks of springing a leak. Frits was ideally suited as a partner in such a venture. The Cremers possessed two automobiles, and Jacob had no objection to lending his aging 1904 Peugeot Type 66 to the boys for their experiments. In the garage of Duin en Kruidberg, the boys had plenty of room to tinker to their hearts’ content. Air-filled rubber tires were prone to puncture on the badly paved roads of the day. The solution that Tony and Frits tried to develop was a steel shackle belt that would be attached to the wheels by a system of springs and torsion rods. This effort might be classified as a form of “reverse engineering”: going back to the massive wheels that had been used on carriages and coaches, with modifications. The garage space and the project budget had to come from Jacob Cremer, yet Tony’s father Herman was prepared to file the patent application on May 24, 1909.25 In the meantime Tony and Frits had the time of their lives trying to make the old Peugeot go as fast as it possibly could. They practiced alongside the railroad tracks, the car’s leather sides taut in the wind, trying to keep up with the fast train into Amsterdam, and had themselves photographed as racing drivers, standing next to the vehicle.26 For over half a year the boys tinkered away at the Peugeot before the project ran aground. They found that a patent similar to theirs had already been filed in France.27

The disappointment over the car tire was only the beginning of bad news. In December 1909 Tony and Frits were called up for military service, a distinctly unappealing prospect for the pair. They attempted to simulate flat feet at their medical examinations, but both young men were found to be physically fit.28 Tony was drafted in March 1910, and for him there was no option but to obey. The Cremers were in a much better position to dodge the draft. Jacob Cremer launched an appeal, and on his father’s instructions Frits left on a world tour with his older brother Marnix and a distant cousin. For a year Tony and Frits were almost completely out of touch with each other. When Tony reported for duty at the Naarden barracks, his friend was dancing at the Penang Golf Club in Malaysia. Indeed, Frits’s departure had been so unexpected and quick that the two friends hardly had time to say their goodbyes. Frits wrote to his father from Malta to inquire what had become of the automobile tire scheme.29 Until December 1910 Jacob Cremer remained involved in proceedings to exempt his “frail son” from military service.30

Naarden itself, a small fortress town with about four thousand inhabitants, surrounded by earth walls and moats, was a bitter disappointment for Tony. Centuries of occupation by rotating garrisons had left its traces in the streets. Although the town was one of the key strongholds in the water defenses southeast of Amsterdam, contemporary photographs show it to have been in poor repair. Within the town’s high earth walls, both the bigger and smaller houses were built low to shield them from gunfire. On many houses the brickwork showed traces of soot and of humidity. Window frames and doors were in need of a fresh layer of paint. Only the main street, with the town hall and church, was presentable. The “murderous” steam tram that ran from Amsterdam to Laren passed through the street to the Utrecht gate. Except for military movements—guns and supplies being moved around—this practically summarized all traffic there was in Naarden. For a city lad from Haarlem, the small garrison town was less than boring: it was “a hole to hang yourself.”31 Unlike his fellow conscripts, Tony hardly appeared to notice the pub-like recreational facility that stood next to the parade ground in front of the Promers barracks.

Weeks went by with the usual drills and exercises for the new recruits, weeks in which Tony did his utmost to get noticed in a negative way by falling out of step as often as he dared. Although his grades for gymnastics had been the highest on his report cards at school, he now pretended not to be able to run because of his flat feet.32 The coincidence that he had caught a bad cold and thus coughed continually worked to his advantage. He was sent to the sick bay to recuperate, a recovery that was encouraged by confining patients to a strict diet of bread and milk. Yet Tony persevered in his act. His performance was convincing enough for the doctor to send him to the Naarden military hospital for examination. Although conditions there were a step up from those in sick bay—the hospital wards had real beds instead of wooden bunks, and there was a table with chairs for recuperating soldiers who were allowed out of bed—the diet of milk, water, and rice did not agree at all with Tony. He begged his mother, “Please send me some butter and cookies and lots of sugar (dark brown and white) and some sausages in a tin? A little money please ± 2,50.”33

Tinkering with an automobile: In 1909 this was Tony Fokker’s favorite way to spend the day. To stay abreast of punctured tires, Tony and his friends “reverse engineered” a wheel with a steel shackle belt, attached by a system of springs and torsion rods. The goal was to make the customary bicycle pump superfluous. FOKKER HERITAGE TRUST, HUINS, THE NETHERLANDS

Getting an early discharge proved difficult, however. The military doctor took hardly any notice of Tony’s complaints and prescribed strict bed rest, plus weekend detention. He was not allowed off the hospital premises and was confined to its enclosed garden even on Sundays, which he feared would be “boring to death.” His subsequent plea to be allowed to visit his sister in Amsterdam for a couple of hours was grudgingly granted, and he was allowed to visit his sister on a Monday evening.34

That visit proved a prelude to a speedy return to civilian life. When he jumped off a moving tram in Amsterdam, he lost his balance and fell, badly bruising his ankle on the curb.35 The immediate result was that he was taken to the Amsterdam military hospital, where all they gave him were wet bandages.36 Again he was prescribed bed rest. The game lasted for two more weeks, while Tony complained in whining letters to his mother that the charade was taking up the time he had planned to spend on reequipping his sailboat. “My chocolate powder is all gone now and the sugar too,” he wrote to his mother. “Please send, or better bring a whole lot, the sooner the better. I am completely out of things. I gave the guy who inspects the postal parcels a cup of my choc, although he is not allowed to take this. Sic! I’m really not splashing it about, but the cups here are really big and the bread is barely buttered and dry.”

Mama also sent him money. Tony needed little encouragement to use that to further his early release, promising his ward sergeant twenty-five Dutch guilders—about twice a man’s weekly wages then—to help him obtain a discharge. His letter continued:

Help of your ward sergeant is worth its weight in gold. To remain good friends with him is really a prerequisite, because if such a man is against you, there is no escaping. I’ve promised him 25 guilders if he gets me a discharge. (A boy from another ward has done the same in similar circumstances). It looks like a lot at first sight, doesn’t it, but don’t forget what you’re gaining with this and his help is the main cause that things are going so quickly for me (well quickly for here, that is, mind you). He is ward sergeant and assistant to the doctor in all operations, hence makes good money, so you can’t send him off with a small bribe. Anyways, I’ll be cheaper off here than in Naarden. Patience alone is now the cue.37

The money would prove well spent for Tony. The financial massage helped procure his medical discharge. It was the first time money enabled him to wriggle out of commitments, and it was a lesson that would stay with him. Dreaming of a career as an aviator, he returned home in the automobile his parents gave him for his twentieth birthday.