Japan became a concern to Britain with the end of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in the 1920s, and the subsequent Japanese invasion of China saw the relationship worsen. As the Sino-Japanese War deepened, the threat to British interest in the Far East increased, even to the point that the Japanese openly attacked Western commercial and military shipping, such as HMS Ladybird. However the British Government continued to be ambivalent towards Japan and any measures it took were weak and ineffective.

Although from a diplomatic standpoint Britain continued to take a soft line with Japan, from a military point of view Britain was worried. In the 1930s the largest and most prosperous British assets in the Far East were Singapore and Malaya and as such they were heavily defended. However, successive studies have all concluded that Hong Kong could not be defended effectively and the British Government never maintained the level of troops that was deemed necessary to protect it. Nevertheless, the British Government initiated the Hong Kong Defence Scheme 1936. The aim of the 1936 defence scheme focused on transforming Hong Kong Island into a fortress with light defences and delaying positions in Kowloon and the New Territories. The task of the Hong Kong Garrison was to ‘defend the Colony from external attack and deny the use of the harbour and the dry dock to the enemy’. The strategy was to hold Hong Kong Island as a fortress and wait for rescue by the British fleet. It was therefore essential that Hong Kong should protect its harbour as its top priority. The Japanese were seen to be the main threat to Hong Kong and the military strategists deemed that the main avenue of attack would be by sea and not by land. To attack Hong Kong by sea the IJN would have to navigate five layers of defences: first naval mines with indicator nets and anti-submarine booms; next, the coastal guns; and if the former two layers of defence were penetrated, beach defences consisting of a series of pillboxes, wires and landmines; on the island, high on the hills, infantry strongpoints to defend against localized landings and to stop penetration; and finally a reserve force to counter-attack and destroy any enemy landings.

Bren carriers on manoeuvres somewhere in the New Territories on the mainland. This type of grassy, hilly terrain is typical of much of the New Territories, where much of the initial fighting occurred. Command of the high ground is vital to any military operation. (IWM)

This set of anti-shipping booms was laid at the eastern entrance of Victoria Harbour, close to where the Japanese landing on Hong Kong Island took place. Together with indicator loops and controlled minefields, they formed the core naval element of the 1936 Defence Scheme. (IWM)

In addition the 1936 plan called for extensive construction of bunkers, trenches and blocking positions across bottleneck approaches to Kowloon and a main line of defence, a mini Maginot-style line of trenches and pillboxes across the mountains north of Kowloon. The army component listed only three infantry battalions plus the local Hong Kong militia, the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps (HKVDC), a regiment-plus sized unit of armoured cars, engineers, artillery, anti-aircraft guns and infantry, all to be organized into three elements: the mainland brigade, the island brigade and the garrison reserve. In the 1936 defence scheme the RAF was expected to be exceptionally strong with one reconnaissance squadron, one fighter-bomber squadron, two torpedo squadrons and one flight of air auxiliary spotter planes from the HKVDC. The navy consisted of a couple of destroyers, a flotilla of MTBs and gunboats, and assorted patrol craft.

These activities were further boosted when the IJA occupied Guangzhou, and Hong Kong was effectively surrounded. Limited conscription was introduced but applied to only non-Chinese males for service with the HKVDC. Local Chinese mainly served in non-combat roles such as ARPs, medical units etc. As a result of the increasing Japanese threat, the Hong Kong Garrison was boosted to four regular infantry regiments: two British (one medium machine-gun role) and two Indian. In support were two regiments of coastal artillery, one regiment-plus worth of field artillery as well as a regiment of anti-aircraft guns. The Royal Navy in Hong Kong consisted of the 2nd MTB flotilla with eight BPB6 60 MTBs 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 (60ft, 29 knots, twin torpedoes with eight Lewis guns) and MTB 26 and 27 (ex-Chinese Navy Kuai 1 and 2, British Thornycroft 55ft CMB), four shallow-draught, flat-bottom river gunboats (HMS Cicala, Tern, Moth, and Robin) and four old World War I S-class destroyers HMS Thracian, Thanet, Scout and Tenedos (left in 1939 for Singapore) as well as a Navy sloop HMS Cornflower plus an assortment of tugs, boom defence vessels and minelayers. The Fleet Air Arm was represented by three Supermarine Walruses – single-engine reconnaissance amphibians co-located with the Air Force in Kai Tak Airport. The Royal Air Force was the weakest of the three services with only four Vickers Wildebeest torpedo/light bombers and a flight from the HKVDC consisting of a single Avro 621 Tutor, two Hornet Moths and two Cadet biplanes.

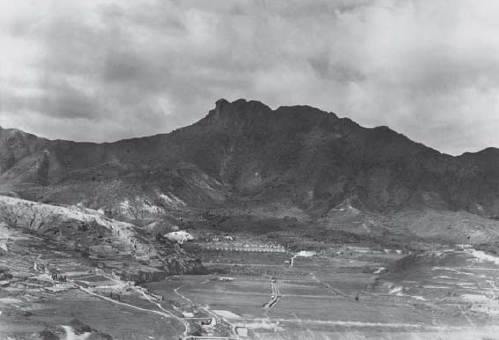

The main landmark of Kowloon, Lion Rock Mountain. Looking north, the plain below is now Western Kowloon, today a middle-class area full of high-rise buildings. The Lion Rock forms a ridge of mountains that stretch east–west across the northern tip of Kowloon where the Gin Drinkers Line was situated. (NAM)

B Coy, 1st Battalion the Middlesex Regiment, somewhere in the New Territories, 1940. Note they are armed with Short Magazine Lee-Enfields. This picture was taken by Private Henry Chick of B Coy, 1 Middlesex, who died in the sinking of the Lisbon Maru in 1942. (NAM)

However, in the early years of World War II, Britain was preoccupied with national survival; it was unavoidable that little or no effort was placed on the defence of the Empire, especially far-flung outposts like Hong Kong. Not only were there no additional reinforcements, the outbreak of war in Europe resulted in many of the better soldiers being sent back there, with the less capable left in Hong Kong. Furthermore during years of peacetime garrison duties many had spent more time drinking cocktails and attending concert parties than honing their fighting skills.

Governor Sir Geoffrey Northcote lobbied London vigorously for a stern response to the continuous Japanese harassment – flying warplanes, sinking junks and fishing vessels, as well as the infiltration of Hong Kong by Taiwanese fifth columnists (Taiwan had become a Japanese colony in 1895). With his hands tied, in October 1940, the ailing Northcote recommended the withdrawal of the garrison ‘in order to avoid the slaughter of civilians and the destruction of property which would follow a Japanese attack’, knowing that in all practical respects Hong Kong was indefensible against a determined Japanese attack. However, London opposed this suggestion – ‘such action, it was felt, would discourage China, encourage Japan and shake American faith in Britain.’ A key and probably the most critical political consideration was the never-ending tussle between China and Britain over the sovereignty of Hong Kong. Ever since Hong Kong had been ceded to Britain in 1841, the British had feared that, if it was given up without a fight, it would be that much more difficult to reclaim it under British rule after the war. London felt that it was important to ‘show Chiang Kai-shek [the leader of Nationalist China] the reality of our intention to hold the Island’.

The Hong Kong Chinese Regiment raised as a machine-gun battalion on 3 November 1941 with an establishment of six Chinese NCOs and 46 men, led by two British officers and three regular NCOs. By Christmas Day 1941, 31 of the original 57 members were killed or wounded, a 54 per cent casualty rate in three weeks. (IWM)

However, London continued to avoid any request for extra troops. The request by Major-General A. E. Grasett DSO MC, GOC China, for reinforcement was flatly refused, the only help offered being from Indian or other colonial forces. In 1941 the newly appointed British GOC in the Far East, Air Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham again pressed his superiors to reinforce the garrison of Hong Kong. His request fell on deaf ears.

In July 1941 Grasett, a Canadian who had just retired from his appointment as GOC China, returned to Britain by way of Canada and, whilst in Canada, acting on his own initiative, called upon his former classmate Maj. Gen. Crerar, Chief of Canadian General Staff, and lobbied for reinforcement, arguing that the ‘addition of two or more battalions to the forces then at Hong Kong would render the garrison strong enough to withstand for an extensive period of siege’. On 5 September 1941, shortly after reaching London, Grasett met with the British Chief of Staff and argued strongly for reinforcement, and suggested that Canada might supply the additional units to Hong Kong. The British chiefs were convinced and they persuaded the reluctant Churchill to change his mind. In the light of the looming Japanese threat, the defence of Malaysia/Singapore, the linchpin of the British Empire in the Far East, was boosted from nine battalions to 32 and the dispatch of two capital ships (HMS Prince of Wales and Repulse) to the area was seen to be enough of a deterrent to the Japanese against any ‘inappropriate’ action against British interests in the Far East, Hong Kong included.

The original Hong Kong war strategy was only to defend Hong Kong Island and deny the harbour to the enemy. A solitary battalion (the Punjabis) was to fight a series of delaying actions in the New Territories and conduct a short defence with three battalions on the Gin Drinkers Line to buy time to demolish stores, powerhouses, docks, wharves, clear food stocks, vital necessities, etc., on the mainland and then withdraw to Hong Kong Island and fight until relief arrived – either from Singapore or from the Americans in the Philippines.

The Gin Drinkers Line (a mini-Maginot Line) was located some 18km south of the Sino-Hong Kong border. The line was so named because it began to the west of Kowloon at a place called Gin Drinkers Bay. It stretched 17km across the hills of Kowloon to the eastern edge of the Kowloon Peninsula. The Gin Drinkers Line was expected to hold the Japanese for three weeks or more before the battalion retired to Hong Kong Island to hold on as long as it could while waiting for relief and while the mainland was evacuated. To defend Hong Kong effectively, the 1937 war plan estimated that it would require four battalions to fight an effective delaying action and up to seven to defend the Gin Drinkers Line, not to mention back-up from an adequate air force plus a blockade-busting navy. However, with one army brigade available and a virtually non-existent air force, the plan to hold the Gin Drinkers Line and the defence of the mainland was soon abandoned and the defence facilities remained incomplete and wasted away in the tropical heat.

The local Chinese were generally not engaged in any of the war preparations nor integrated into any of the war plans until very late. The biggest contingent was a group of volunteer Chinese that served with the HKVDC. On the regular army side, 150 Chinese were recruited in mid-1941 for service with the 5th Antiaircraft Regiment. The Hong Kong Chinese Regiment, formed only on 3 November 1941, with officers borrowed from the British and Indian Regiments and 52 Chinese junior NCOs and other ranks that were barely trained. There was a troop of Royal Engineers staffed entirely by Chinese and a handful saw service with the Royal Navy and in the Dockyard Defence Corps. However, in the auxiliary services such as the ARPs, auxiliary police, nursing services, St John Ambulance and fire service, the participation of Chinese was somewhat higher.

Part-time soldiers of the HKVDC in training. Like all Territorials, training took place after work or during leisure time. Soldiering in the pre-World War II period was segregated along racial lines and all the young men in the picture are Eurasian; most probably they are soldiers of the No. 3 Eurasian Coy. (IWM)

Because of concern about their loyalty in the event of conflict with China, Hong Kong Chinese were not recruited in large numbers until the 1930s, when threat of war with Japan became serious. By December 1941, 25 per cent of the Royal Engineers were local Chinese. Seen here are Hong Kong Chinese serving as regulars in the Royal Engineers. (IWM)

This unwillingness to engage the Chinese wholeheartedly in the defence of Hong Kong probably had to do with the general prevailing attitude of the time. Pre-war propaganda often ridiculed the Japanese as short-sighted and incompetent. The fighting ability of Japanese soldiers was played down; success in China was dismissed, as the Japanese had never encountered ‘quality opposition’; furthermore the general consensus was that Japanese weapons were not up to European standards. In general the British were confident that if the colony was attacked, provided they had reinforcements, they could hold out indefinitely.

In September 1941, Hong Kong welcomed the news that two additional Canadian battalions were being made available to Hong Kong. Maltby immediately dusted off the pre-war plan of holding the Gin Drinkers Line. He devised a plan that called for three infantry battalions on the mainland (2 Royal Scots, 5/7 Rajputs and 2/14 Punjab, elements of HKVDC with support of four troops of the Hong Kong and Singapore Royal Artillery and the Coastal Artillery), and three infantry battalions (1 Middlesex, Royal Rifles of Canada and Winnipeg Grenadiers) reinforced by the bulk of the HKVDC holding Hong Kong Island. These were to be split into two brigades: the Island Brigade, named Hong Kong Infantry Brigade (HKIB) commanded by Brigadier Lawson of the newly arrived Canadian reinforcements and the mainland brigade, named Kowloon Infantry Brigade (KIB), commanded by Brigadier Wallis. The two Canadian regiments arrived in Hong Kong on 16 November 1941.

The Gin Drinkers Line was located in a very commanding position, perched on a range of mountains that stretched across the northern part of the Kowloon Peninsula. The line had certain inherent weaknesses. It had little depth and could be easily outflanked, two locations being particularly dangerous: Customs Pass and the gap between Golden Hill and Laichikok Peninsula (the area around Gin Drinkers Bay). Owing to the extensive front, each battalion’s layout consisted of a line of platoon placements, the gaps between which were covered by fire by day and by patrols at night. One company from each battalion could be kept in reserve and it was normally located in a prepared position, covering the most dangerous approaches. The reserve company of the centre battalion (2/14 Punjab) was employed initially as forward troops to cover the demolitions and to delay the enemy’s initial advance.

Battery command post of the HKSRA in 1941. The HKSRA was the largest colonial unit ever raised by Britain. It was essentially a British-officered, Indian Regular Artillery Regiment, recruited for service, as the name suggests, in Hong Kong and Singapore. (IWM)

The last-minute change of plan, to include a defensive force on the mainland at short notice, meant that many of the means of support such as communication lines, artillery and mortar registrations were not complete before the Japanese attacked. The lack of artillery shells and mortar bombs was another hindrance. For instance, in the worst case, the 2/14 Punjab had undergone one 3in. mortar practice session, of a few rounds only, but ammunition in any appreciable quantity did not arrive until November and then only 70 rounds per battalion, both for war and for practice. Hence these mortars were fired and registered for the first time in their battle positions and 12 hours later were in action against the enemy. For the 2in. mortar the situation was even worse. Not until the start of the battle did the troops receive any live bombs and consequently the first time they used this weapon was against the enemy! Because of the lack of transport, trucks or even mules, everything, including ammunition, had to be moved by hand and, on hilly terrain like Hong Kong, that would have been a test of endurance to say the least.

On 6 November 1941 The Japanese Imperial Headquarters ordered its Commander-in-Chief China to prepare plans for the capture of Hong Kong. The 23rd Army of the China Southern Expeditionary Army Group under the command of Lt. Gen. Sakai Takashi with Maj. Gen. Kuribayashi Tadamichi as Chief of Staff was to form the core of the force and all preparations were to be complete by the end of November 1941. The aim of the plan, known as ‘Operation C’, was to ‘capture Hong Kong within ten days’. Operation C was a relatively simple set of plans. First a blocking force was to prevent interference by the Chinese from the rear and secondly an invasion force was to lead the attack. The 23rd Army, consisting of four divisions plus a mixed brigade and two infantry regiments, was assigned the task of attacking Hong Kong. Of the four divisions only one, the 38th, played an active role in the invasion.

The attacking force was a combined arms effort; first there was a naval blockade and bombardment, combined with air attack on key installations, before a land invasion by elements of the 38th Division, consisting of 228th, 229th and 230th Regiments. They adopted a classic left, right and centre approach. The right force was to strike to the west, making a large hook curving right to clear the Castle Peak Road and strike at the vital point around the left flank of the Gin Drinkers Line around Laichikok Peninsula, while the centre force was to exploit the centre of the line, and the left force was to cross Tidal Cove (Tolo Harbour) heading towards Kai Tak Airport and eastwards towards Devil Peak, a major battery position. The aim was to destroy the British on the mainland and force Hong Kong to surrender by intense bombardment. If the British continued to hold out, the invasion of the island would have only just begun.

Protecting the rear against the Chinese National Army of the 7th Military District and Communist Guerrillas and securing the assembly areas was the work of the 66th Regiment (normally part of the 51st Division, for the duration of the invasion, it was attached to 38th Division). The 66th was also responsible for occupying and securing the rear zones in the New Territories and Kowloon while the three spearhead regiments fought. This rearguard force was divided into columns known by the names of their commanders, Kitazawa, Kobayashi, Sato and Araki.

The IJA chose the closest point between Kowloon and Hong Kong Island, on the eastern end of the island around Lyemun Passage (at its narrowest, only 410m separate the mainland with Hong Kong Island). Once they had landed, they were to move rapidly inland to capture the vital point of Wongneichong Gap and then turn west and south to capture Victoria City and the rest of Hong Kong.

The naval element was divided into two parts, the Bombardment Group and the attack Group. Attached to the force were approximately 300 members of the Naval Infantry (SNLF). The IJAF contributed to the invasion with 56 light bombers and fighters of the First Air Brigade under Col. Habu Hideharu. The mission was to support the land-based troops by destroying the Royal Air Force and Royal Navy.

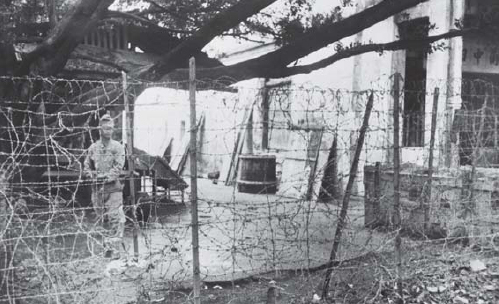

Sha Tau Kok village sits astride the Sino-Hong Kong border. The border bisects the main shopping street of Sha Tou Kok village, creating the effect of a mini-Berlin in the Cold War. Note the IJA soldier on the other side of the barbed wire. (IWM)

_______________________

6 British Power Boat Company – a maker of high-speed boats in Britain