The Two-Ocean Navy Act of 1940: The Impact on American Preparedness for World War II

Commander of the Asiatic Fleet, Rear Admiral William F. Fullam, observing a display of naval aviation on Armistice Day, 11 November 1918, stated: “They came in waves, until they stretched almost from horizon to horizon, row upon row of these flying machines. What chance, I thought, would any ship, any fleet have against an aggregate such as this? You could shoot them from the skies like passenger pigeons, and still there would be more than enough to sink you. Now I loved the battleship, devoted my whole career to it, but at that moment I knew the battleship was through.”1

Common perception has long held that the advocates of the large, dreadnought, big-gun capital ship actively frustrated and obfuscated aircraft carrier and general naval aviation development in the interwar period. While the battleship advocates, especially those associated with the Bureau of Naval Ordnance (aka the “Gun Club”) refused to view the aircraft carrier as the key capital ship of the future, many primary players of the period nevertheless did not discourage the development of naval aviation. Rather, most battleship advocates viewed the carrier as an adjunct to the battle line, performing fleet support roles such as scouting, reconnaissance, and gunfire spotting. Key leaders such as Rear Admiral William A. Moffett, Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) from 1921 until his untimely death in an airship accident in 1933, pushed naval aviation development with great vigor and positive results. In Congress, naval aviation advocates such as Representative Carl Vinson (D-GA), formed a corps of powerful advocates who ensured that the legislative and budgetary process supported naval aviation through the fiscally challenging 1930s. The ultimate expression of naval expansion following the lean interwar years, as characterized by ship and personnel drawdowns in accordance with naval armament treaties (1922 and 1930), came in the summer of 1940 with the two-ocean naval legislation (Vinson-Walsh Act). That legislation, the result of which was the massive United States Navy of World War II, will be examined in light of the impact on the evolution and development of naval aviation that rapidly replaced the battleship as the ultimate capital ship in the immediate post–Pearl Harbor era.

Left to right: Representative Carl Vinson (D-GA); Secretary of Navy Francis P. Matthews; Admiral Louis E. Denfeld, Chief of Naval Operations; and Admiral Arthur W. Radford, Commander, Pacific Fleet, 6 October 1949.

While many directions might be taken, this chapter examines three essential topics. Part I addresses the contextual background to the evolution of aircraft carriers and naval aviation in the interwar period of 1919–1939. Part II examines the legislative process, particularly the actions of Representative Vinson, the major political champion of naval expansion and aviation. Finally, part III looks at the results of the 1940 legislation in practical terms and how it put to sea the fleet of 1943–1945 that won the war in the Pacific and ensured Allied domination of the Atlantic against the German Kriegsmarine. While other ship types resulting from the 1940 legislation will be mentioned, this chapter focuses on aircraft carriers and naval aviation.

PART I—THE INTERWAR CONTEXT: CARRIERS IN THE WINGS

In the interwar period, several prominent admirals and decision makers publicly stated the importance of naval aviation to fleet operations. While not yet proclaiming aviation as the essential core of the fleet supplanting the battleship, many senior officers nonetheless captured the essence of the new aviation thinking. Two examples illustrate this dynamic. In 1933, British Royal Navy First Sea Lord Admiral of the Fleet Alfred Chatfield commented: “The air side is an integral part of our naval operation . . . not something which is added on like the submarine, but something which is an integral part of the navy itself, closely woven into the naval fabric. Whether our air weapon is present or not will make the whole difference to the nature of the fighting of the fleet and our strategical dispositions. That is a fact which will increase more and more, year by year.”2

Of great importance to the acceptance of Navy aviation in the United States was the attitude of Admiral William S. Sims. Sims had commanded U.S. naval forces in Europe during World War I and had a keen appreciation of naval aviation as pioneered by the Royal Navy. As President of the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island, from 1919 to 1922, he encouraged war game simulations to validate the concept of aviation not only as a fleet support adjunct, but also as an offensive weapon. Sims argued against the “unreasoning effect of deadly conservatism” on the part of those senior officers unable or unwilling to recognize naval aviation’s potential.3 In testimony before Congress in 1925, the Admiral, then retired, concluded decisively that the fast carrier was the capital ship of the future and that it carried far more offensive capability than a battleship.4 With a supporter of Sims’ stature, naval aviation could only prosper in the long haul.

In truth, few top officials argued against naval aviation. Rather, it was the role played by aircraft that generated controversy. Immediately following World War I, even later aviation advocates doubted that aircraft carriers would ever play more than a supporting role in fleet operations. Then-Commander John H. Towers, Naval Aviator #3 and eventual Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, testified to the Navy General Board in 1919 that he doubted that aircraft operating from an airplane carrier would “last very long.”5 Despite doubts about the utility of shipboard-based aircraft, the General Board reported to Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels that the United States should ensure air supremacy or at least meet on equal terms any potential adversary. Not only did the General Board assert that aviation had become an “essential arm of the fleet,” but that “fleet aviation must be developed to the fullest extent.”6 The real argument in those days of limited defense budgets was not over whether the airplane was needed, rather it was over aviation’s role as an adjunct for fleet support or as an offensive weapon based on its own lethality. Indicative of Navy aviation’s rise to prominence was the creation of the Bureau of Aeronautics in August 1921 under Rear Admiral Moffett. Answering only to the Secretary of the Navy (as was common to all Navy bureaus), the creation helped insulate early aviation from those officers most adamantly opposed to Navy air power.

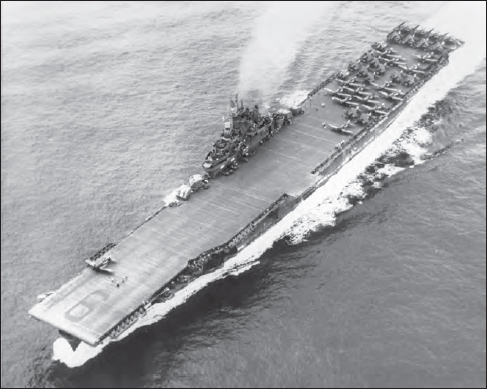

Technology and geography also played a role in the evolution of carrier-based aviation. Various techniques for launching and recovering aircraft from a deck underway had been conducted by the Royal Navy during World War I; however, due to the creation of an independent air arm with the establishment of the Royal Air Force in April 1918, British navy aviation lost momentum and control of its own destiny. Thus, by the mid-1920s, the U.S. Navy surged ahead of Britain in carrier development. The modification of the collier Jupiter into the USS Langley (CV-1) by 1922 provided the platform for testing and perfecting carrier operations, including tail hooks for landing traps. Eventually, wheeled aircraft replaced floats in frontline aircraft. By the time the first operational fleet carriers arrived in 1927 (Saratoga and Lexington), technology and doctrinal changes had moved the aircraft carrier into an offensive rather than simply a fleet support mode.

By the 1920s, Navy planners assumed that a maritime conflict with Japan in the Pacific loomed inevitable and that Navy aviation would play a great part in supporting fleet operations, both as support for the battle line (reconnaissance, scouting, and gunfire spotting) and in actual offensive operations. Fleet battle problems using carriers in an offensive role showed the potential for carrier-delivered air raid operations. In the 1930s, the Navy perfected effective dive-bombing techniques, making the airplane a potentially deadly weapons system even against maneuvering vessels. And the Navy realized that forward naval operations in the Western Pacific against Imperial Japan far from land-based stations such as the Hawaiian Islands (assuming the initial loss of the Philippine Islands) could only be conducted with robust air support; only dedicated carriers could transport, support, launch, and recover aircraft on a routine, sustained basis. Geography thus aided in the evolution of pro-aviation thinking, technology, and—gradually—war-fighting doctrine.

Another milestone in Navy aviation development occurred in 1925 with the Morrow Report. Appointed in 1925 by President Calvin Coolidge as a study group composed of nine members drawn from Congress, the Army, the Navy, and the private aviation industry to examine both military and commercial aviation policy, the Morrow Board conducted four weeks of hearings, interviewed almost a hundred expert witnesses, including the Secretaries of War, Navy and Commerce as well as representatives of the fledgling aircraft industry. Headed by Dwight Morrow, the recommendations of the board set the standards for Navy aviation for decades and led to critical congressional legislation in 1926. Among the most far-reaching results were the creation of the Office of Assistant Secretary of the Navy (Aeronautics) and the requirement that all commanding officers of aircraft carriers, seaplane tenders, and naval air stations must be qualified naval aviators. While the Assistant Secretary position was eventually left vacant by the 1930s, the command requirement ensured a career track for Navy aviators that appealed to those interested in professional progression and major command opportunities.7

The board advocated that a “strong air force was vital to national security and there must be a strong private industry and long-term continuing program of procurement which was essential to the creation of adequate engineering staffs and the acceleration of new developments.” In this regard, the board concluded that the private aircraft industry represented a vital component of national defense and that “government competition with civil industry should be eliminated.”8 In other words, the government appropriated the funds and specified the technical objectives and requirements for military aircraft, but the private sector executed the design and manufacture of military aircraft. It is important to note that a key board member was the young congressman from Georgia, Carl Vinson.

PART II—THE LEGISLATIVE IMPERATIVE

With the changes in the international climate by the early 1930s and the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, a former Assistant Secretary of the Navy and ardent Navy supporter, carrier aviation accelerated. The political will for naval expansion had finally returned after fifteen years in hibernation. Representative Vinson, who became Chairman of the House Naval Affairs Committee with the Democrats taking the majority in 1931, immediately set about the legislative process. Vinson served in the House of Representatives for fifty years, much of which as Chairman of the House Naval Affairs Committee and later Armed Services Committee. From the Service side, the new Commander in Chief, US Fleet (CinCUS) Admiral Joseph Mason Reeves, a qualified naval observer, encouraged Navy aviation, thus setting the stage for the necessary legislative, budgetary, and senior leadership support required for dramatic aviation expansion.

Beginning in December 1931, Vinson met with various Republican and Democratic lawmakers as well as Secretary of the Navy Charles Francis Adams, to lay the legislative foundations for accelerated naval shipbuilding.9 Funded by the National Industrial Recovery Act (NRA) of 1933, USS Yorktown (CV-5) and USS Enterprise (CV-6), both laid down in 1934 and commissioned in 1937 and 1938, respectively, formed the backbone of carrier forces in the early months of the coming Pacific War.10 In January 1934, flush with the first funding success for fleet modernization and capital ship construction, Vinson announced that he intended to push for millions of dollars in additional public works funds in the 1935–1936 fiscal years.11 From the start of the Roosevelt administration, Vinson championed naval rearmament. While others dithered and hoped for peace in the world through disarmament, treaties, and downsizing, Vinson understood the dangers of military unpreparedness and more importantly, the effort, funding, and lead time required to ensure preparedness. Just after the 1932 election that swept the Democrats back into the White House and into the congressional majority, Vinson began his crusade for rearmament, stating, for example, that “our national defense in time of peace is allowed to decline and to grow weak, and when war comes, as unhappily it does, billions of dollars are poured out in the vain effort to build up our Navy and to create an Army to meet an emergency that we find upon us. Again and again we must be taught that soldiers cannot be made in a day and that it takes years to create ships.”12

In conjunction with Senator Park Trammell of Massachusetts, Chairman of the Senate Naval Affairs Committee, Vinson achieved the next great legislative success in 1934—the Vinson-Trammell Act. Objections to the bill emanated from two quarters: those who saw the bill as unnecessary government spending in the midst of the Great Depression and isolationists. Vinson argued that the stimulus aided economic recovery, especially in hard-hit industrial areas such as steel and shipbuilding. Additionally, he pointed out that the United States had not even built up the Navy to the treaty limitation displacement tonnages imposed by the 1922 Washington and 1930 London naval agreements. Thus, American national security relative to the two potential maritime adversaries—Great Britain and Japan—suffered serious deficiencies.13 He won the argument. The bill passed, authorizing over $5 million for new ship construction to bring the Navy up to treaty strength with over 100 new warships and over 1,200 aircraft.14 However, the bill did not actually appropriate any specific money; rather, it authorized funding for future appropriations. Despite the political opposition, President Roosevelt signed the bill on 28 March 1934. Navy aviation, which had expanded little in the interwar years with only three operational carriers, benefited greatly from the legislation, prompting Admiral Jonas Ingram to comment that the legislation represented a seminal event “looking toward the continued operating efficiency and future expansion of naval aviation.”15 In truth, the Vinson-Trammel Act broke the logjam of dithering, complacency, and calculated inattention to Navy aviation that characterized the first decade and a half of the interwar period. As the treaty limitations expired at the end of 1936, the United States now clearly had set a new course in naval rearmament. The authorizations and appropriations of the 1930s based on Vinson’s efforts set the stage for the 1940 Two-Ocean Navy Act and the dramatic expansion of U.S. naval forces.

By the late 1930s, events in Europe and Asia took an ominous direction. With the refusal of key nations to continue naval arms limits, even the appropriations resulting from the 1934 Act seemed inadequate for national security. New Chief of Naval Operations Admiral William D. Leahy recommended an authorization to exceed the limits of the earlier Vinson-Trammel Act.16 Congress responded positively. For example, legislation in 1935 authorized commissioning six hundred new Naval Reserve pilots.17 Thus, the foundations of the 1940 Act were laid. In the interim, however, incremental authorizations and appropriations boosted Navy shipbuilding. On 3 March 1938, the Naval Affairs Committee recommended a massive increase in the building program even beyond Roosevelt’s recommendations. The appropriation passed the House of Representatives as H.R. 9218 by a vote of 294 to 100 and on 17 May 1938, the president signed what came to be called the “2nd Vinson Act.” The result—a 20 percent expansion of the fleet beyond the projected treaty size of just two years earlier and the authorization for acquisition or construction of Navy aircraft up to three thousand airframes.18 While isolationists railed against the increased appropriations, the argument that defending the United States well out to sea versus at the shoreline won the day. Indications that Japan had almost 300,000 displacement tons of new naval vessels already under construction certainly charged the debate in favor of naval expansion. As in the heady days of U.S. naval expansion forty years earlier, the influence of Rear Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan’s admonition that national security lay in decisive battle for command of the sea through great battle fleets overwhelmed arguments for isolationism or governmental economy.19

The 1939 naval appropriation bill included the laying down of two new battleships of the South Dakota class. Within a week of signing the 1939 appropriation, still based on the original 1934 authorization, President Roosevelt recommended constructing an additional two battleships.20 For the future of Navy aviation, the president called for two additional aircraft carriers, which would become USS Hornet (CV-8, third ship of the Yorktown class that reached the fleet in 1941), and ultimately, the main fleet carrier–class leader of the last two years of the war, USS Essex (CV-9). Eventually, twenty-six Essex-class carriers were ordered and twenty-four completed.21 Additionally, the 20 percent increase appropriated funds for 950 more aircraft. The USS Wasp (CV-7) and USS Ranger (CV-4), both launched in the 1930s and smaller designs than the Yorktown class, rounded out the carriers as war erupted in the Pacific. The need for shore air facilities drove further congressional legislation in 1939, resulting in an appropriation for naval aviation facilities at Kaneohe and Pearl Harbor, Hawaii; Midway Islands; Wake, Johnston, and Palmyra Islands in the Central Pacific; Kodiak and Sitka, Alaska; San Juan, Puerto Rico; Pensacola, Florida; Norfolk, Virginia; Quonset Point, Rhode Island; and Tongue Point, Oregon.22

Disregarding objections from many prominent legislators, in March 1940, Vinson set the stage for the most critical of all the Vinson bills, the Two-Ocean Navy Act in June. He announced as early as November 1939 that he intended to propose mammoth Navy authorization legislation in 1940 calling for three additional carriers as well as other ship types and to allow for long-term, low-interest government loans to aid shipbuilders. Additionally, Vinson’s proposed legislation sought to lift the requirement that a minimum of half of all construction must occur in government yards such as the Philadelphia Navy Yard, Brooklyn Navy Yard, Norfolk Navy Yard, Puget Sound Navy Yard, and so forth, and grant the Navy Department authorization to award noncompetitive bid contracts. Beginning in January 1940, Vinson’s Naval Affairs Committee conducted hearings on H.R. 8026, known as the Vinson Naval Expansion Act of 1940. Arguing that Japan had embarked on a massive carrier-building program beginning in March, he shepherded through Congress an additional appropriation for three new carriers as part of a two-year authorization program leading to an 11 percent fleet expansion.23 The bill passed the House by a striking 305 to 37 vote. With quick Senate passage, the law became effective on 14 June 1940. The carriers USS Yorktown (CV-10) (formerly Bon Homme Richard), USS Intrepid (CV-11), and USS Hornet (CV-12) (formerly USS Kearsarge) resulted from the legislation; CNO Directive of 20 May 1940 initiated the contracting process.

Vinson had many allies in the Navy for his expansive proposals, especially for naval aviation. As BuAer Chief beginning in 1939, Rear Admiral John Towers had an immense impact on the shape of the new Vinson Navy particularly in providing the professional expertise required to shape the legislation. Vinson frequently consulted Towers on aviation matters. Towers had direct access to the president, Chief of the Army Air Corps, and the senior executives of the aircraft industry, thus he played a pivotal role in the events of March to June 1940 in terms of ship and aircraft acquisition. The Chairman of the Naval Affairs Committee frequently tasked the admiral to draft the legislation for fleet expansion even though that task lay clearly beyond the scope of his authority and responsibilities at BuAer. The crucial day of deliberations between Towers, Vinson, and members of the committee, 22 May 1940, shaped the course of legislative events into June as Vinson pushed his agenda through Congress with great alacrity. The noted naval air historian, Clark G. Reynolds, asserts that “it is no exaggeration to say that more was done toward creating the modern air-centered wartime and postwar U.S. Navy on the twenty-second of May 1940 than had been in years of struggling by BuAer and the fleet’s aviators, Towers foremost among them.” In short, the process that led to the Two-Ocean legislation in June 1940 represented a symbiosis of professional and legislative leaders of incredible energy, expertise, and influence at a critical moment in the evolution of U.S. Navy air power.24

Thus, on the eve of the Battle of France in May–June 1940, the various appropriations came to a total of five new aircraft carriers. But, illustrating the continued dominance of the battleship as the main capital ship type, the same legislation called for twenty-one new dreadnoughts. By 1940, however, only the two North Carolina–class battleships had been launched, with all other existing battleships rapidly nearing the end of usable service life. However, the fleet had in commission five carriers of relative youth, though of more or less capability. A far-sighted observer in spring 1940, aware of the Japanese carrier-building program, might easily conclude that the ascendancy of the aircraft carrier and power projection through the air was at hand.

On 19 May 1940, the headline in the Washington Post announced the German capture of Antwerp, Belgium, one of Europe’s busiest ports.25 With the collapse and surrender of France and evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force from Dunkirk, it became clear that the United States’ future security relied upon an immediate and profound armed forces expansion. In a classified memorandum dated 22 May 1940, Major Matthew B. Ridgeway, future United Nations commander in Korea, analyzed in stark language the dangerous security situation facing the country: “It is not practicable to send forces to the Far East, to Europe, and to South America all at once, nor can we do so to a combination of any two of these areas without dangerous dispersion of force . . . we cannot conduct major operations either in the Far East or in Europe due . . . to a lack of means at present.” Copies of the memorandum went to the president, the Chief of Naval Operations, the Secretary of the Navy, and to the Chief of Staff of the Army who expressed his “complete agreement with every word of it,” according to an annotation added 23 May 1940 as a NOTE FOR RECORD.26 The fall of France and the realization that the United States lacked the means and resources to fight a multi-front war against the fascist powers jolted Congress and the administration into action, with Vinson leading the charge.

On 2 May, Vinson introduced a bill calling for increasing Navy aircraft from 3,000 to 10,000 air frames and pilots from 2,602 to 16,000 along with the required training facilities as well as a further 11 percent increase in hulls, which included an additional carrier.27 In early June, he ramrodded the bill through Congress (known as the 3rd Vinson Act).28 Events moved swiftly as German Wehrmacht panzers charged across a hapless France; the new Navy authorization became law on 14 June, the day following the fall of Paris.29

After the success of the June bill, the new CNO, Admiral Harold Stark, testified before Vinson’s committee that the Navy required a 70 percent increase in fleet assets to meet the two-ocean challenge. In dramatic but understated fashion, the chairman asked the CNO: “In view of world conditions, you regard this expansion as necessary?” Stark responded directly and crisply: “I do, Sir, emphatically.”30 Vinson upped the ante with an increase of a previous proposal for a $1.2 billion authorization to an over $4 billion bill to meet the 70 percent expansion goal. Although it bore the name of Senator David I. Walsh (D-MA), Chairman of the Senate Naval Affairs Committee, the key instigator of what came to be called the Vinson-Walsh Act or Two-Ocean Naval Expansion Act was the Georgia congressman. Recognizing that the threat lay in two seaward directions, the bill proposed a massive naval building program that allowed the United States to fight a two-ocean maritime struggle against Germany and Italy in the Atlantic and Japan in the Pacific. Admiral Mahan had argued for a concentration of forces. The Two-Ocean Navy Act sought to create such an overwhelming force that the U.S. Navy could bring to bear Mahan’s concept of decisive concentration in both theaters simultaneously—a bold move. Admiral Stark, at an executive session of the Naval Affairs Committee, argued for 439,000 tons of new construction, but Representative Vinson pushed the amount further to 1,250,000 tons. The proposed bill grew larger by the hour. The committee added a further 75,000 tons for additional aircraft carriers, patrol boats, shipbuilding facilities, and improvements to the factories and foundries that manufactured armor plate and naval artillery. The committee unanimously approved the bill and it moved quickly to the House floor. The Vinson-Walsh Act (H.R. 10100) passed with only two hours of debate in the House of Representatives on 22 June and an hour in the Senate on 11 July without a single “nay” vote.31 On 22 June, the government of France signed an armistice amounting to a complete capitulation to Hitler’s Germany, underscoring the dramatic change in U.S. security needs.

H.R. 10100 provided for 385,000 tons in new battleship construction, but only 200,000 tons in aircraft carriers. But, in the post–Pearl Harbor environment, as it became obvious that the maritime struggle in the Pacific would be an airman’s war, the battleship appropriation over time transferred to carrier construction. A single-line memorandum from Navy Budget Officer Captain E. G. Allen, of 20 July 1940 to all Navy bureaus and offices, the Navy Department, and Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, announced in dry and understated comment the most overarching and dramatic expansion of the United States Navy in history. Captain Allen simply stated that “Bill H.R. 10100 (the 70 percent Naval Expansion Bill) was approved by the President on 19 July 1940.”32 The impact of that statement on the Navy, the United States, and the world’s future would be dramatic. On the 30th, Admiral Stark advised the Secretary of the Navy that based on a meeting on the evening of 25 July with the president, negotiations for contracts for two battleships, six large-gun heavy cruisers, ten light cruisers, and three fleet carriers of the Essex class could begin. Interestingly, the remaining five battleships included in the 70 percent bill were “not cleared and no contracts are to be negotiated for them.”33 The statement could be interpreted as indicating that as early as a year and a half prior to Pearl Harbor, the Navy realized that the carrier had arrived as the primary fleet capital ship. However, despite the advancements in aviation and carrier technology as pioneered in the interwar period, most senior officers in 1940 still viewed the airplane as an adjunct to the battleship. Pearl Harbor would change all of that.

PART III—THE NEW VINSON NAVY

Based on the legislation from early June (11 percent expansion) and H.R. 9822, which streamlined the contracting process, the Navy proceeded without hesitation to order new construction at the beginning of July. Within two hours of the president signing the legislation, the Navy Department let contracts for forty-five warships.34 Pursuant to the Two-Ocean Navy Act, the Navy contracted for seven additional carriers, all of which eventually reached the fleet for war service in the Pacific.35 Construction numbers starkly illustrate the power of the naval appropriations legislation. By early September 1940, American shipyards had 201 naval vessels under construction.36 In January 1941, multiple shipyards had under construction 17 battleships, 12 carriers, 54 cruisers, 80 submarines, and 205 destroyers.37 Despite this rapid increase in shipbuilding activity, Navy leaders worried that the potential Axis threat could not be met based on the established two-ocean timetable. Then Commander of the Atlantic Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, in a 30 July 1941 letter to the Navy Board chairman pointed out that while Hornet was due to be completed by the end of 1941, follow-on CVs would not be commissioned until early 1944 based on the thirty-six-month construction cycle. King further and forcefully advised that the “current scheduled rate [of construction] is wholly inadequate and requires to be expedited . . . [and] considering the accelerating importance of air power, the conversion of suitable and available ships to carriers should be undertaken at once.”38 Not only did American shipyards respond with an expedited schedule, but accelerated hull conversion programs spurred further acquisition of two critically important carrier types, the Independence-class light carriers and multiple escort carrier classes.

Carrier construction contracts went out to major shipyards, including Bethlehem Steel’s Quincy, Massachusetts, shipyard, Newport News Shipbuilding in Virginia, and the New York Navy Yard in Brooklyn, New York. For example, on 1 October 1940, Bethlehem Steel accepted the contract offered by the Navy on 9 September 1940 for carriers CV-16, CV-17, CV-18, and CV-19 (USS Lexington, USS Bunker Hill, USS Wasp, and USS Hancock)—all to be built at the company’s Fore River Yard in Quincy, Massachusetts, for a price of $191,200,000, or $47,800,000 per ship. All four carriers eventually saw Pacific service. USS Lexington, the first of the group when launched in September 1942, saw action beginning with the Gilbert Islands Campaign that initiated the Central Pacific thrust of the overall multipronged strategy against Japan (other prongs included the Southwest Pacific (SOWPAC) thrust under General Douglas MacArthur, the South Pacific (SOPAC) prong under Admiral Chester Nimitz, the B-29 strategic bombing campaign, the unrestricted submarine maritime interdiction campaign, and the China-Burma-India (CBI) Campaign under Lord Louis Mountbatten with U.S. forces in a supporting role). USS Hancock, launched in January 1944, reached Pacific Fleet in time for the Philippines and Iwo Jima campaigns.39

In 1940 the American shipbuilding industry, buffeted by a decade of economic depression, stood ready, able, and willing to ramp up on a massive scale. As a further inducement to speed construction, Congress suspended the profit-limiting provisions of the Vinson-Trammell Act in legislative action on 8 October 1940, a feature that had roiled relations between the Roosevelt administration and the manufacturers to the point that no company would agree to begin construction or manufacture of ships or aircraft until the restriction had been modified.40 In the contract acceptance letter from Bethlehem Steel, Vice President A. B. Homer pointed out to the Secretary of the Navy that “execution of the contracts in question will be postponed until that Act [profit limitations clause included in the 1934 Vinson-Trammel Act] shall have been repealed.”41 Additionally, the issue of new plant facilities required by Bethlehem Steel to accommodate not only the four new carriers, but the additional cruisers included in the contract, became a source of contention. The company required over $10 million to construct these facilities within the specified time frame; without these upgrades at Fore River, the ships could not be started. A new welding building; transportation equipment; cranes; sheet metal, paint, and machine shops as well as an additional wet basin and so forth all had to be constructed to accommodate the rapid shipyard expansion. For accelerated wartime construction, the normal amortization and depreciation of new facilities and plant expansion over an extended period could not be relied upon. Clearly, Congress needed to grant protection to manufacturers from rapid postwar drawdowns and other costs that would not be part of the normal, peacetime business cycle. Indeed, Admiral Towers had been able to let only a single contract with the Stearman Company for training biplanes, such was the reticence of companies to accept contracts without financial protections. With German forces occupying Paris and Great Britain under air siege in autumn 1940, no one in Congress, the Roosevelt administration, or the Navy desired any delays. An old saying in naval aviation goes, “maximum speed, minimum drag, speed is life.” Clearly, Congress understood this imperative with war imminent and responded accordingly with the Internal Revenue Act of 1940, passed on 8 October, that repealed the profit ceilings on ships and aircraft, established a five-year plant amortization schedule, and set up a tax structure to guarantee sufficient manufacturer profits.42

The contract for the Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock Company of Newport News, Virginia, went out from the Secretary of the Navy on 11 September. Similar to that awarded to Bethlehem Steel, the contract called for the construction of CVs 12–15 (USS Hornet [originally Kearsarge, but renamed Hornet after the loss in action of the original Hornet (CV-8) at the Battle of Santa Cruz on 27 October 1942], USS Franklin, USS Ticonderoga, and USS Randolph). The contract award also specified that each ship had to “conform substantially to the contract plans and specifications to be furnished by the Navy Department for Aircraft carrier CV-9.” Since USS Essex (CV-9, launched in July 1942) and USS Yorktown (launched January 1943 and originally USS Bon Homme Richard, but renamed Yorktown following the loss of the original Yorktown (CV-5) at Midway in June 1942) were then under construction at Newport News, the shipyard stood ready from a technical viewpoint to construct the new class of carriers. In fact, Newport News had constructed the earlier Yorktown and Enterprise, both launched in 1936 and Hornet, which would be launched in December of that year. Thus, their expertise in large-carrier construction stood at a pinnacle by late 1940. It is interesting to note that the cost per unit for the Newport News carriers came in at $42,090,060, a substantial reduction compared to the Bethlehem Steel price. However, considering that the cost of living in 1940 in Hampton Roads/Tidewater, Virginia, compared to that in the Boston, Massachusetts, area probably was considerably less, the relative costs per ship seem reasonable. Additionally, the more heavily unionized Boston area might also explain a higher per unit cost. Keeping in accordance with the need for rapid delivery, the Navy offered the shipyard an incentive bonus of $3,000 per day under the contractual time of delivery. The Navy also allowed $7 million for acquisition of additional plant facilities required to upgrade the Quincy yard. From a cost and budgetary viewpoint, clearly the carriers built in Virginia made better economic sense. However, the need to build as rapidly as possible to the 70 percent fleet expansion as called for in the Two-Ocean legislation meant that the Navy could not rely upon a single company or yard. Bethlehem Steel did have considerable large-hull construction capability and experience. For example, that yard had built the carrier USS Lexington (CV-2) in the 1920s, USS Wasp (CV-7) launched in April 1939, and also the battleship USS Massachusetts (BB-59) laid down in July 1939. The same dynamic justified the higher costs of building ships in New York at the New York Naval Shipyard in Brooklyn or New York Shipbuilding in Camden, New Jersey, which constructed the USS Saratoga (CV-3) and eventually all nine of the Independence-class light carriers (CVL 22–30). The New York Naval Shipyard, better known as the Brooklyn Navy Yard, constructed the later Essex-class carriers Bennington (CV-20), Bon Homme Richard (CV-31), Kearsarge (CV-33), Oriskany (CV-34), and the late-war USS Franklin D. Roosevelt (CVB-42) of the Midway class launched in April 1945.

Wartime exigency thus played a vital role in carrier construction. With the loss of the battleships USS Arizona (BB-39) and USS Oklahoma (BB-37) at Pearl Harbor, with the time required to repair and refit the remaining damaged dreadnoughts, and with the attrition of the prewar carriers in combat through 1942, the Navy needed the new capital ships as rapidly as possible. While the older carriers, cruisers, and destroyers of the Pacific Fleet had been able to blunt the Japanese Pacific advance through the various naval engagements in 1942—including the battles of the Coral Sea in May, Midway in June, Eastern Solomons in September, Santa Cruz in October, and the multiple actions in the Solomon Islands in support of the Guadalcanal Campaign—by early 1943, the Pacific Fleet had been reduced to two operational carriers: USS Enterprise (CV-6) and USS Saratoga (CV-3). Any hope of initiating the Central Pacific prong, which reflected the long-standing War Plan Orange calling for a rollback offensive in the Central Pacific leading to a decisive, Mahanian-style great battle fleet engagement against the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) in the Philippine Sea followed by maritime interdiction and bombardment of the Japanese home islands, depended on the arrival of the new Vinson Navy. By March 1943, the Joint Chiefs of Staff contemplated the strategic plans for the war against Japan. MacArthur argued for the SOWPAC campaign aimed at retaking the Philippine Islands. Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet, as supported ably by his new chief of staff, Admiral Raymond Spruance, the hero of Midway, argued for the Central Pacific advance. In a compromise solution in June 1943, the Joint Chiefs of Staff agreed upon a dual-pronged advance with the Navy–Marine Corps leading through the Central Pacific island archipelagoes and the Army and Army Air Force with Navy support thrust through the Southwest Pacific (primarily the northern New Guinea coast) toward Rabaul and eventually the Philippines. But a potential problem loomed. The SOPAC campaign had moved along briskly and by early 1943 Guadalcanal had been secured as American forces advanced rapidly up the Solomons chain. In the SOWPAC, MacArthur had initiated operations in New Guinea with Operation Cartwheel in June. So long as the Central Pacific thrust remained a strategy in waiting, the Japanese ability to outflank American and Allied forces from the north, even to the point of cutting off the communications route to Hawaii and the United States, remained an issue. With a robust campaign aimed at the center, Japan would have to defend on many fronts and in many spots to maintain its defensive perimeter, which would of necessity prevent enough concentration of forces so as to threaten the SOWPAC and SOPAC theaters. In other words, the sooner the Vinson Navy could be on station, operational, and ready to fight with new carriers and improved combat aircraft, the better.

American industry answered the call. For example, the contract with Newport News required completion of USS Lexington within fifty-seven months of contract award. For the fourth carrier, USS Randolph, the contract stipulated seventy months from award to delivery. The date of the contract award letter from the Secretary of the Navy to Newport News was 11 September. Lexington was launched on 30 August 1943 and commissioned on 29 November 1943, merely thirty-seven months rather than the contractually required fifty-seven. Similarly, Randolph’s time to delivery was only forty-eight months rather than the mandated seventy (commissioned 9 October 1944). In like manner, contract deliveries for the Bethlehem Steel Quincy Yard for Lexington from time of contract award to delivery took only twenty-nine rather than the prescribed forty-three months, and Hancock’s delivery in only forty-three months beat the contractual time by twenty-three months.43 Armed with the new construction ships and airplanes, a testament to the incredible industrial capacity of American industry and the productivity of American workers, the Navy initiated the Central Pacific thrust against the Gilbert Islands with the amphibious assault against Tarawa Atoll on 20 November 1943, an operation that could not have been even contemplated had not the shipbuilders delivered the new carriers and other ships funded by the Two-Ocean legislation well ahead of schedule. Few archives so vividly illustrate the scope of this economic and industrial power than the 1 January 1943 message to the Commander in Chief (COMINCH), Navy from Captain Donald B. Duncan, USN, Commanding Officer, succinctly stating that “USS ESSEX, CV-9, PLACED IN FULL COMMISSION AT 1700 THIS DATE.” Only thirteen months after the destruction of the Pacific Fleet battleships at Pearl Harbor, the first of the new class of aircraft carriers intended for the destruction of the Japanese Empire, became operational.44

An additional issue complicated the construction plan. Did the Navy require carriers quicker or a newer, more robust design? The Bureau of Construction and Repair and the Bureau of Engineering (merged in 1940 into Bureau of Ships or BuShips) pointed out in early July, after passage of the legislation, but prior to the president’s signature, that to build CVs of the newer design would require additional months compared to using the current Hornet-class design. If the first four newly appropriated ships, starting with CV-9, were built to the Yorktown/Hornet design, then the estimated time to delivery would be thirty months versus the newer design requiring forty-four months. Total tonnage did not present a problem with either class design. To build five at 19,800 tons each would bring the program well under the budgeted tonnage. To build four Yorktown/Hornet designs and one new design of 26,500 tons came to 105,700 tons or just under the limit.45 Such were the design decisions facing the Navy as Vinson pushed through ever-greater naval legislation. However, the events of 1940 in Europe had the effect of removing qualms about building the best carrier design available in the most expeditious manner. Accordingly, the Navy decided on the new design beginning with USS Essex.

Essex’s design dated to 1939 when the Navy still operated under the terms of the treaty imitations (20,000 tons gross displacement). From a practical standpoint, she appeared much like an improved Yorktown class. But, with the outbreak of war and the subsequent renunciation of treaty tonnage limits, the United States removed all restrictions, resulting in the eventual, more robust Essex design. An increase in armor and flight deck area gave improved survivability and space for aircraft deck parking. For air defense, the 5-inch guns, mounted in singles on the Yorktowns, became twin mounts—two turrets forward and two aft of the island superstructure. Engineering space improvements with an alternating boiler room/machinery room design gave better damage control capability. At 872 feet and with a 33,000-ton displacement, the new Essex far outstripped the older Yorktown-class design. Changes in 1942 included a deck-edge elevator, air and surface search radar, and an increase in anti-aircraft defenses built around the Swedish Bofers model 20-mm and 40-mm rapid-fire guns mounted primarily in rows (20 mm) and quad configurations (40 mm) on platforms and catwalks just below the flight deck. As a result of the decision to proceed with the larger, more capable design, shipyards constructed twenty-four Essex-class fleet carriers by war’s end with the bulk of the hulls in service by late 1943 to mid-1944, a truly remarkable achievement. From the June 1940 legislation, ten Essex-class carriers resulted, all of which saw significant action in the Pacific. Arguably, the single most important American warship of the war, Essex slid down the ways on 31 July 1942.46

Additionally, smaller ship types such as the Independence-class (CVL-22) light carrier (launched 22 August 1942) and escort carrier (CVE) emerged from the early war experience. Admiral Stark advised BuShips that a Cleveland-class light cruiser originally authorized in the 1934 bill and ordered in 1940 (USS Amsterdam, CL-59) would be converted to the new Independence-class light carrier as funded by the Two-Ocean legislation. Convoy protection in the Atlantic proved to be a critical mission for naval aviation as German submarines, commerce raiders, and Luftwaffe aircraft threatened the logistical supply line to Great Britain and the Soviet Union. Nine CVLs saw war service as well as over eighty escort carriers, starting with the USS Long Island (CVE-1) launched 2 June 1941.47 In October 1940, Roosevelt directed that the Navy obtain a merchant hull for conversion to an escort carrier, resulting in the first of a long line of highly capable warships used primarily in the anti-submarine warfare and convoy escort roles. USS Long Island (CVE-1), converted from the merchantman Mormacmail and completed in June 1941, did service in the Pacific in delivering Marine fighter and bomber squadrons to Guadalcanal before returning to San Diego for duty as a training vessel. Roosevelt’s plan to convert merchant ships to small 6,000- to 8,000-ton carriers capable of carrying ten to twelve fighters for convoy escort proved a valid concept with the success of the British escort carrier HMS Audacity in the Atlantic. With speeds of eighteen knots and better, the CVEs could travel faster than any convoy and almost as fast as the best German submarines on the surface. Primarily carrying Wildcat fighters of twenty or more per ship, the CVEs provided substantial air cover for the Atlantic convoys. In the Pacific, they provided close air support (CAS) to the land forces once an amphibious landing had secured the beachhead. In the Leyte Gulf engagement, USS St Lo (CVE-63) and USS Gambier Bay (CVE-73) sank under the pounding of Vice Admiral Kurita Takeo’s battleship-cruiser force. Many CVEs transferred to the British Royal Navy. The Navy designated thirty-five CVEs, constructed or converted under the Two-Ocean legislation, for assignment to the Royal Navy, including eight of the original hulls from 1942.48 Of the Casablanca-class (CVE-55 through CVE-104), the first purpose-built CVEs from the keel up and constructed in the Kaiser Company’s Vancouver, Washington, shipyard, all but two served in the Pacific Theater. The late-war Commencement Bay–class ships (CVE-105 through CVE-124), built in the Todd-Pacific and Allis-Chalmers yards in Tacoma, Washington, rounded out the CVEs but only three ships saw combat action. Previous classes had been conversions primarily from merchantmen and oilers. War realities drove the eventual development of designs and capabilities of ships and aircraft, but the funding emanating from the 1940 legislation provided the ability to literally invent new ship types as war exigencies dictated.

These and later ships carried aircraft such as the Grumman F6F Hellcat fighter, Vought F4U Corsair fighter-bomber, TBF Avenger torpedo bomber, and SB2C Helldiver dive-bomber that replaced the prewar design F4F Wildcat, SBD Dauntless, and TBD Devastator types. Funds for the thousands of aircraft of the new types resulted from the Two-Ocean legislation and by 1943–1944, largely replaced the early war models. The legislation increased the number of Navy aircraft to 15,000 as well as the expansion of shore facilities to accommodate the expanded Navy air assets. Forty-two existing naval air stations required substantial upgrades. Many Naval Reserve aviation bases needed modification; seven new reserve bases required establishment.49 Additionally, the increase in pilot numbers first stimulated by the 1935 appropriation continued as 1940–1942 appropriations dramatically increased the need for aviators. Some characteristics of these new aircraft illustrate the tremendous advances in naval aviation technology—capability and design made possible by the various naval appropriation bills between 1935 and early in the war.

The Vought F4U-4 Corsair first flew on 1 May 1940. With its distinctive gull wing shape and powerful Pratt and Whitney R-2800-18W radial engine that produced 2,100 hp, first production models arrived by September 1942. With a top speed of 446 mph and a 26,200-foot ceiling, the Corsair proved a versatile and deadly fighter and fighter bomber able to engage in air combat and carry both bombs and rocket ordnance. The Curtiss SB2C Helldiver replaced the Dauntless. Designed in 1939, production contracts went out in November 1940, just after the contracts for the Essex-class ships. The first combat employment of the airplane occurred in strikes against the Japanese air and naval base at Rabaul on New Britain. The TBF/TBM Avenger first entered combat in 1942 at the Battle of Midway. Designed to replace the unsuccessful Devastator, the large three-man aircraft carried torpedoes, bombs, or depth charges depending on the mission. Despite its durability and survivability, the F4F Wildcat suffered technologically compared to the A6M Zero fighter, and a replacement finally arrived in August 1943. The F6F Hellcat, with a maximum speed of 380 mph at 14,000 feet and a service ceiling of 37,300 feet outclassed and outperformed the Zero in many critical performance characteristics. With a range of close to a thousand miles, the Hellcat gave the carriers an extraordinary combat radius and became the primary naval fighter for the remainder of the war. Aircraft, however, were expensive. A Corsair ranged from $61,000 to almost $70,000 per airplane depending on the acquisition date. A Hellcat fighter ran $54,000. By contrast, the older Dauntless dive-bomber came in at $32,800, while the Wildcat cost $42,000.50 In the rapid expansion period following the fall of France, the 1940 appropriations provided the funding for the new 15,000-aircraft Navy.

To support the aviation expansion, new bases needed construction and older facilities upgraded. Funding for such public works projects came from the various appropriations. Illustrative of the cost is the estimate provided by Chief of BuAer, Rear Admiral John S. McCain, in May 1943 requesting approval for additional public works projects at naval air stations totaling $16,598,636. For the period from 1 September 1943 to 30 June 1944, the new chief, Rear Admiral D. C. Ramsey, proposed $93,834,500, a stunning figure by contemporary standards.51 Increased pilot training followed aircraft acquisition, a dynamic also funded in the various appropriations. Illustrating this dynamic, then-Captain Arthur W. Radford reported the status of flight training as of 30 June 1942 showing 6,901students in the training pipeline, including a number of British officers.52 Fortunately for the Navy, Vinson and Congress accounted for the massive overhead cost of fielding and supporting a robust fleet and air expansion, without which the new force could not be sustained.

Naval expansion and, in particular, the growth of naval aviation, intensified after the Pearl Harbor attack of 7 December 1941; authorization and appropriation bills became common throughout the first three years of the U.S. war effort. Representative Vinson remained the centerpiece of naval legislation until his eventual retirement in 1964. Nonetheless, the single most important legislative and ultimately far-sighted action for America’s ability to win the maritime struggle with Japan and sustain the beleaguered British and Soviet allies was the Two-Ocean Navy Act of 1940.53 The Act provided the forces with which Admiral Nimitz executed the Central Pacific campaign to the Japanese home islands as envisioned in the Navy’s War Plan Orange and supported the SOPAC/SOWPAC campaigns with overwhelming carrier-based air power. By the time of Japan’s September 1945 surrender, sixteen of the seventeen Pacific Fleet carriers resulted from Vinson-sponsored legislation.54 And, it allowed the U.S. Navy to fight a two-ocean struggle against the German Kriegsmarine in the vital Atlantic Theater. Finally, the Two-Ocean legislation, when combined with the various other appropriation and authorization bills in the late 1930s and early 1940s, vaulted the United States Navy into the world’s pre-eminent maritime force based on command of the sea through command of the air, a continuing dynamic guaranteed by the flourishing of naval aviation since 1940.

NOTES

1. Proceedings of the Special Board and Records of Evidence (Eberle Board), United States National Archives (hereafter NA), Record Group (hereafter RG) 80. Rear Admiral Fullam observed over two hundred aircraft based at Rockwell Field near San Diego as they performed fly-bys for over three hours to celebrate the end of World War I.

2. Lord Chatfield, First Sea Lord, Inskip Inquiry, 13 July 1936, London: National Archives of the United Kingdom, CAB 16/151.

3. Admiral Sims made these comments in an address to the Naval War College class of 1921 at the college on 19 November 1921.

4. Clark G. Reynolds, The Fast Carriers: The Forging of an Air Navy (Huntington, NY: Robert E. Kreiger, 1978), p. 1; NA, General Records of the Department of the Navy, 1798–1947, Secretary of the Navy General Correspondence (hereafter SECNAV): 1940–42, RG 80, 370/19/27/17, Box 20, Morrow Board Report Summary dated 12 July 1944 and Resume of Report of Morrow Board, Vol. 3, dated 30 November 1925.

5. NA, Department of the Navy, Records of the General Board Transcripts of Hearings, 1917–1950, Vol. 2, 1919, RG 80, Box 4, Vol. i–iii.

6. Letter to SECNAV dated 23 June 1919, Bureau of Aeronautics, General Correspondence (hereafter BuAer), NA, RG 72, Entry #15.

7. Reynolds, The Fast Carriers, p. 15. The Morrow Board Report was printed in the USNI Proceedings 52 (1926), pp. 196–225. In addition to the personnel requirements, the Board called for the acquisition of a thousand aircraft in the 1926–31 time frame.

8. SECNAV, RG 80, 370/19/27/17, Box 20, Morrow Board Report Summary dated 12 July 1944, and Resume of Report of Morrow Board dated 30 November 1925.

9. New York Times (hereafter NYT), 3 December 1931, p. 12 and 5 December 1931, p. 2.

10. USS Ranger (CV-4), the first purpose-built carrier from the keel up proved inadequate for fleet operations due to size and stability limitations. However, follow-on designs using the lessons pioneered aboard Langley and perfected by Saratoga and Lexington, came forward beginning with the Yorktown class.

11. Washington Post (hereafter TWP), 9 January 1934, p. 9.

12. Congressional Record, 72nd Congress, 2nd Session, in Congressional Record, 63rd Congress—88th Congress (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1914–1965) (hereafter CR), 22 February 1933, 4720–23.

13. Vinson’s OPEDs in NYT, 23 January 1934, p. 2; NYT, 29 January 1934, p. 4; and The Atlanta Constitution, 28 January 1934, p. 7A.

14. CR, 74th Congress, 1638.

15. Admiral Jonas Ingram, “15 Years of Naval Development,” Scientific American (November 1935), p. 234.

16. NYT, 5 January 1938, p. 11; TWP, 26 January 1938, pp. 1, 7.

17. Many of these Naval Reserve aviators went on to form the core of experienced pilots upon which the huge personnel expansion of 1940 was based. But other capital ships were not overlooked in the 1935 legislation. For example, the North Carolina–class battleships North Carolina (BB-55) and Washington (BB-56), the first U.S. battleships built since World War II, resulted from the naval expansion legislation of 1935.

18. TWP, 29 January 1938, pp. 1, 5; NYT, 29 January 1938, pp. 1, 4, 5.

19. Alfred Thayer Mahan, The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783, originally published in 1890 and based on Mahan’s Naval War College lectures, profoundly altered naval strategic thinking in not only the United States, but in Europe and Asia as well. Previously non-naval states such as Imperial Germany, Japan, China, Austria-Hungary, and Italy raced to build larger and more capable capital ships in search of the decisive great battleship clash far out to sea.

20. USS Massachusetts (BB-59) and USS Alabama (BB-60). The original two BBs were USS South Dakota (BB-57) and USS Indiana (BB-58).

21. The early 1943 aircraft configuration of the Essex class consisted of four squadrons—36 fighters, 36 dive-bombers, and 10 torpedo bombers or 91 total aircraft with 9 planes stored and broken down in reserve. By the war’s end, the typical air group complement stood at 36 Hellcat fighters, 36 Corsair fighter-bombers, 15 Helldiver dive-bombers, and 15 Avenger torpedo planes or 102 total aircraft.

22. Many of these new naval air facilities played prominent roles in World War II and beyond. Naval Air Station Pensacola is the basic training activity for naval aviation. Quonset Point became one of the original Naval Construction Battalion (SEABEE) training and headquarters sites and is now a Rhode Island Air National Guard facility. Naval Air Station Norfolk still supports Hampton Roads naval activities.

23. CR, 76th Congress, 3rd session, 2731–33, 2750, 2752; TWP, 13 March 1940, pp. 5, 6.

24. For the pivotal role played by Rear Admiral Towers in the events of spring 1940 that resulted in the Two-Ocean legislation, see Clark G. Reynolds, Admiral John H. Towers: The Struggle for Naval Air Supremacy (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1991), pp. 315–31.

25. TWP, 19 May 1940, p. 1.

26. War Department, SECRET MEMORANDUM: Subject: National Strategic Decisions, WPD MBR dated 22 May 1940 (declassified 24 October 1973), NA, Records of the War Department Special and General Staffs, War Plans Division, General Correspondence, RG 165, 270/4175–77.

27. TWP, 22 May 1940, p. 4. The 11 percent bill included funding authorization for 21 warships, 22 auxiliaries, and 1,011 aircraft.

28. CR, 76th Congress, 3rd session, 2750.

29. The bill authorized the increase in air frames from 3,000 to 10,000, billets for 16,000 pilots and funding for the construction of twenty new naval air stations, both in the continental U.S. (CONUS) and at various outside of continental U.S. (OUTCONUS) locations, particularly in the Pacific.

30. The Atlanta Journal, 18 June 1940, p. 1.

31. The Atlanta Constitution, 11 July 1940, p. 1; NYT, 23 June 1940, p. 1, 14; CR, 76th Congress, 3rd session, 9064–65, 9078, 9570. The bill provided for 385,000-tonnage battleships, 200,000-tonnage carriers, 420,000-tonnage cruisers, 250,000-tonnage destroyers, 70,000-tonnage submarines. Within two hours of the signing of the bill, contracts began going out from the Navy Department.

32. MEMORANDUM from Captain E.G. Allen dated 20 July 1940, NA, SECNAV, RG 80, A1-3/A18 (340213-17), 11W3/25/32/2, Box 2.

33. Letter from Chief of Naval Operations to Secretary of the Navy dated 30 JUL 1940, NA, SECNAV, RG 80, 370/19/14/1-2, Box 20 (Declassified IAW NNDD813002 by NARA on 17 September 2009).

34. NA, SECNAV, Aircraft Carrier Awarded, RG 80/11W3/25/32/2, Box 2; CVA Contracts List, RG 80/11W3/25/32/2, Box 2; NYT, 2 July 1940.

35. NA, SECNAV, RG80, CV-12/L4-3 Aircraft Carrier, 11W3/26/6/1, Box 324. USS Franklin (CV-13), USS Ticonderoga (CV-14), USS Randolph (CV-15), USS Lexington (CV-16), USS Bunker Hill (CV-17), USS Wasp (CV-18), and USS Hancock (CV-19).

36. CR, 76th Congress, 3rd session, Appendix, 5721–22.

37. Ibid., 6130ff.

38. SECRET MEMORANDUM from Admiral E. J. King, U.S. Navy to Chairman, General Board dated 30 July 1941, NA, General Board Subject File, 1900–1947, RG 80, GB 420–2, 1941–42, Box 63 (declassified 11 February 1972).

39. For example of a contract award for CV-16/17/18 (Lexington, Bunker Hill, Wasp), see NA, SECNAV, CV16/L4-3 Bethlehem Steel, RG 80, 11W3/26/6/1 Box 325.

40. CR, 76th Congress, 3rd Session; Letter from Chief of the Bureau of Ships to Judge Advocate General of the Navy dated 24 October 1940, para. 2, NA, SECNAV, CV12/L4-3 Aircraft Carrier, 11W3/26/6/1, Box 324, For example, the Vinson-Trammell Act required that at least 10 percent of all naval aircraft and engines be manufactured at the Naval Aircraft Factory in Philadelphia and restricted the profit margin of shipbuilders and aircraft manufacturers to no more than 10 percent.

41. NA, SECNAV, CV16/L4-3 Bethlehem Steel, RG 80, 11W3/26/6/1 Box 325.

42. Reynolds, Towers, p. 330.

43. Letter from Lewis Compton, Acting SECNAV to Bethlehem Steed dated 9 September 1940 and Letter from Lewis Compton, Acting SECNAV to Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company, NA, SECNAV, CV16/L4-3 Bethlehem Steel, RG 80, 11W3/26/6/1, Box 325.

44. USS ESSEX Naval Message dated 1 January 43, NA, BuAer, RG 72, 470/63/18/05, Box 72 (declassified NND730026 by NARA dated 17 September 2009).

45. MEMORANDUM from Bureau of Construction and Repair and Bureau of Engineering (n.d.), received Navy Department 17 July 1940, NA, SECNAV, CV/L8-3(11), RG 80, 11W3/26/6/1, Box 322.

46. Paul H. Silverstone, U.S. Warships of World War II (Garden City, NY: Doubleday 1965), pp. 36–48. Yorktown is a memorial/museum ship in Charleston, South Carolina, while Intrepid is berthed in New York as a floating naval air museum, a testament to the enduring legacy of these ships. Lexington served many decades as a training ship in Pensacola, Florida, for thousands of naval aviators for decades following the war.

47. Ibid., pp. 46–64.

48. CONFIDENTIAL MEMORANDUM FOR MR. GATES dated 10 February 1944, NA, SECNAV, RG 80, 370/19/26, Box 1 (declassified IAW DoD DIR 5200.30 of 23 March 1983 by NARA on 17 September 2009).

49. Letter from Chief of Naval Operations to Various Officials dated 22 July 1940, NA, SECNAV, RG 80, 370/19/14/1-2, Box 20 (declassified IAW NND813002 by NARA on 17 September 2009).

50. Cost Trend of Principal Naval Aircraft dated 10 February 1944, NA, SECNAV, RG 80, 370/19/7/15, Box 9.

51. Letter from Chief BuAer to Secretary of the Navy dated 6 May 1943, BuAer, RG 72, 370/19/27/3, Box 34 (declassified IAW DoD Directive 5200.30 of 23 March 1983 by NARA 17 September 2009).

52. CONFIDENTIAL MEMORANDUM from Captain A.W. Radford to Chief, BuAer dated 30 June 1942, NA, BuAer, RG 72, 370/19/27/3, Box 36 (declassified IAW DoD DIR 5200.30 of 23 March 1983 by NARA on 17 September 2009).

53. The 1940 legislation eventually resulted in the following numbers:

1,325,000 tons new construction

New warships

2 Iowa-class battleships

2 Alaska-class battle cruisers

18 Essex-class carriers

27 Baltimore-, Atlanta-, Cleveland-class cruisers

115 Bristol-, Fletcher-class destroyers

43 Gato-class fleet submarines

15,000 aircraft

Numerous repair/tender/support ships

54. Silverstone, U.S. Warships, pp. 36–48. Only USS Saratoga (CV-3), which had been laid down as a battle cruiser during World War I and launched in 1925 could be characterized as a non-Vinson carrier. USS Enterprise (CV-6) resulted from the 1933 National Recovery Act, but Vinson had been a major influence in that appropriation effort. Thus, sixteen of the seventeen Pacific Fleet carriers at the time of Japan’s surrender could be said to have been part of the “Vinson Navy.”