Foundation for Victory: U.S. Navy Aircraft Development, 1922–1945

The sun shone brightly in the Panama sky as the fighter planes from the aircraft carrier Saratoga (CV-3) roared aloft as part of fleet exercises off the coast of the Central American nation. A few days earlier these same planes had launched a surprise “attack” against the Panama Canal that foreshadowed the independent operations of carrier task forces during World War II. On this day, they were part of a mock fleet engagement, with fighter planes escorting bombing and torpedo aircraft. “Climbed so high we near froze to death [and] cruised over to the enemy [battle] line where we discovered all the Lexington planes below us,” wrote Lieutenant Austin K. Doyle of Fighting Squadron (VF) 2B. With the benefits of altitude and surprise, ideal for fighter pilots ready to do battle, Doyle and his division dove into the “enemy” planes, twisting and turning in dogfights. “When we broke off we rendezvoused . . . [and] strafed every ship in the fleet. . . . No other plane came near us.”1

The events of a February day in 1929 described above occurred in the midst of a watershed era in naval aviation, the interwar years bringing a host of momentous advancements on multiple levels. From a technological and operational standpoint, none were as important as the aircraft carrier and the tactical and strategic implications of this new weapon of war. Arguably, the key element of the carrier’s success was its main battery in the form of the aircraft that launched from its decks, the unparalleled progress made in the design and operation of carrier aircraft providing the foundation for the flattop’s success during World War II. Similar progress marked other areas of naval aviation as well. Such was the lasting influence of interwar aircraft development that Lieutenant Doyle, who as a Naval Academy plebe during 1916–1917 served in a Navy with just fifty-eight aircraft of assorted types, could in 1929 write of a carrier strike against the Panama Canal and, later in his career as a carrier skipper, order planes designed on drawing boards of the 1930s to attack Japanese-held beachheads and strike enemy ships over the horizon.2

On the day World War I ended, the U.S. Navy’s inventory totaled 2,337 aircraft, including heavier-than-air and lighter-than-air types.3 While this is an impressive total, given the aforementioned aircraft total of fifty-eight when America entered World War I, the number is deceiving. It is true that flying boats built by the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company operated extensively from overseas coastal bases in the antisubmarine role. Yet, when it came to combat types flown at the front, the majority of naval aviators who deployed overseas trained and logged their operational missions in the cockpits of foreign-built airplanes. As the U.S. Navy developed its plan for aircraft production, the realization of the superiority of foreign designs was apparent to, among others, Commander John H. Towers, the Navy’s third aviator, who before U.S. entry into the war had observed firsthand operations of British aircraft during a stint in England as assistant naval attaché.4 Even after the signing of the Armistice, foreign types retained their importance to the U.S. Navy’s operations. With overseas observers having witnessed the launching of wheeled aircraft from flight decks built on board British ships, aircraft like Sopwith Camels, Hanriot HD-1s, and Nieuport 29s were procured for use in Navy experiments flying landplanes from temporary wooden platforms erected atop the turrets of fleet battleships. Ironically, the performance of these aircraft, built in the factories of England and France, proved a key factor in the shaping of the interwar aircraft building program.5

Indeed, if there was one driving force behind the development of aircraft for the U.S. Navy during the 1920s and 1930s, it was the realization of the importance of shipboard aircraft to naval aviation operations. While this had been on the minds of naval aviation personnel from the beginning—among the earliest experiments conducted were the testing of catapults for launching aircraft from ships—most naval aviators were initially wedded to seaplanes. Upon arriving in Pensacola, Florida, to establish the Navy’s first aeronautical station there in January 1914, Lieutenant Commander Henry Mustin wrote to his wife of the difficulties of finding a suitable site for an airfield from which to operated landplanes and dirigibles: “Personally, I don’t approve of the Naval flying corps going in for those two branches because I think they both belong to the Army.”6 This philosophy would guide aircraft operations during naval aviation’s first decade and beyond, with naval aviator training and operations centered on seaplane operations.7

British experience in World War I, namely the operation of wheeled-aircraft from ships, coupled with the aforementioned experiments on U.S. Navy battleships carried out during winter maneuvers at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, in 1919, prompted a shift in thinking. Weighed down by pontoons, floatplanes simply could not compare with landplanes when it came to speed and maneuverability. Also, ships operating floatplanes, while they could launch them relatively quickly, had to disrupt operations to come alongside a returning aircraft and crane it back aboard. The aircraft carrier, with a deck devoted to the launching and recovery of aircraft, offered the most promise of maximizing the potential of aircraft in fleet operations.8

By 1927, three aircraft carriers—Langley (CV-1), Lexington (CV-2), and Saratoga (CV-3)—had been placed in commission, their presence giving naval aviation heretofore unrealized capabilities in fleet operations and a potential as offensive weapons at sea or against land targets. “The value of aircraft acting on the defensive as a protective group against enemy aircraft is doubtful unless it is in connection with an offensive move,” wrote naval aviator Commander Patrick N. L. Bellinger in his Naval War College thesis in 1925.

The most effective defensive against air attack is offensive action against the source, that is enemy vessels carrying aircraft and therefore, enemy aircraft carriers, or their bases and hangars on shore as well as the factories in which they are built. The air force that first strikes its enemy a serious blow will reap a tremendous initial advantage. The opposing force cannot hope to surely prevent such a blow by the mere placing of aircraft in certain protective screens or by patrolling certain areas. There is no certainty, even with preponderance in numbers, of making contact with enemy aircraft, before they have reached the proper area and delivered their attack, and there is no certainty even if contact is made, of being able to stop them.9

Nine years later, the Navy’s war instructions for 1934 emphasized the importance of seizing the offensive during a fleet engagement. “If the enemy aircraft carriers have not been located, our fleet is in danger of an air attack. In this situation, enemy carriers should be located and destroyed,” the document read. It further stated that if enemy carriers had been located, either with their aircraft on board or their strike groups having been launched, U.S. carrier planes would “vigorously” attack them, “destroy[ing] their flying decks.”10

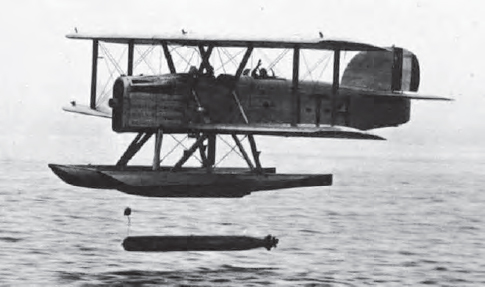

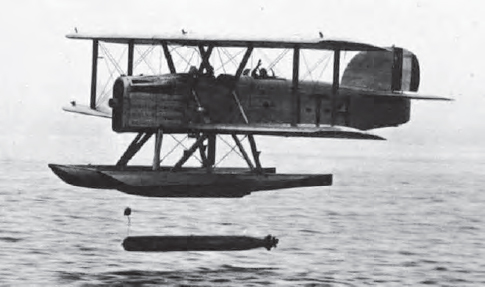

This realization of the threat of enemy air power in a fleet action stimulated tactical thought, which in turn influenced the design of the planes tasked with delivering the blows against enemy carriers. Initially, it was conventional wisdom that torpedoes would be the most effective method of attack against enemy ships, but whether an aerial torpedo or a bomb, the struggle facing aircraft designers was developing aircraft that could carry the weight of the ordnance without compromising too much in the way of speed, maneuverability, and range.11 The first successful torpedo plane design introduced into fleet service was Douglas Aircraft Company’s DT, which was important in more than one respect. First, it was the maiden military plane produced by the company, symbolizing the emergence of a postwar aircraft manufacturing base marked by the opening of such companies as Douglas and Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation. These firms, founded after World War I, joined such wartime entities as the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company, Boeing Company, Glenn L. Martin Company, and the Naval Aircraft Factory—the latter a Navy-owned center for manufacturing and testing of airplanes—in meeting the demands of the Navy’s aircraft programs. Second, due to the weight of aerial torpedoes, while earlier torpedo plane designs were twin-engine ones that were unsuitable for carrier use, the single-engine DT was capable of shipboard operations and of carrying a payload of 1,835 pounds. In fact, on 2 May 1924, a DT-2 version of the design carrying a dummy torpedo successfully catapult launched from Langley anchored at Naval Air Station (NAS) Pensacola, Florida. Finally, the DT pointed to the future in its composition, the traditional wood and fabric used in aircraft, while still present, accompanied by sections of welded steel.12

Naval History and Heritage Command, Naval Aviation News, June 1975

The first successful torpedo plane design was Douglas Aircraft Company’s DT.

Following the DT into production was Martin’s T3M/T4M torpedo planes (versions were also built by Great Lakes with the designation TG), which boasted a higher speed than the DT and could carry versions of the Mk-VII torpedo that was in the Navy’s weapons arsenal during the late 1920s. Its introduction coincided with the first significant involvement of aircraft carriers in fleet exercises, which revealed much about the employment of torpedo planes. Fleet pilots all too quickly found that the operational parameters of their torpedoes left much to be desired, any hope of a successful attack necessitating that the weapon be dropped at an altitude of no more than twenty-five feet with the aircraft flying at a maximum speed of eighty-six miles per hour. Malfunctioning torpedoes were the norm rather than the exception, and the survivability of torpedo planes flying “low and slow” was questionable. Noted a section of the Aircraft Squadrons, Battle Fleet document “Aircraft Tactics—Development of” dated 3 February 1927: “Even with anti-aircraft gunfire in its present underdeveloped stage, torpedo planes cannot hope to successfully launch [an] attack from 2,000 yards and less.” By 1930, there were serious questions as to the wisdom of operating torpedo planes at all.13

The introduction of the Mark XIII torpedo held enough promise for the continuation of the torpedo mission, the weapon capable of being launched at a range of 6,300 yards from altitudes of between 40 and 90 feet and at a speed of 115 mph. The weapon’s weight of 1,927 pounds mandated the introduction of a more capable torpedo plane, the Navy selecting another Douglas design, the TBD Devastator. First flown in 1935, the TBD was cutting edge for its era given the fact that it was a monoplane of all-metal construction with a top speed of over 200 mph. It would be upon the wings of the TBD that torpedo squadrons went to war in 1941 and 1942.14

Developing alongside airborne torpedo attack as an element of naval aviation’s offensive arsenal was aerial bombing. Before World War I and in the years immediately following, battleship officers remained skeptical of the ability of an aircraft to sink a capital ship with bombs. Though bombing tests conducted by Army and Navy airplanes against antiquated U.S. ships and captured German vessels during 1921 proved a success in the damage they inflicted, the fact that the target ships were at anchor with no anti-aircraft defenses left many Navy officers skeptical. Yet, as the first decade of the 1920s progressed, bombing offered increasing promise. “The relative merits of the torpedo plane and the bombing plane has [sic] been a much mooted question recently,” Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics Rear Admiral William A. Moffett told an audience at the Army War College in 1925. “Potentially, the aircraft bomb is, I believe, the most serious menace which the surface craft has to face at the present time.”15 The following year, operations in the fleet focused on a particular type of bombing attack that offered the best chance to make Moffett’s potential menace a real one. On an October day off the coast of San Pedro, California, sailors on the decks of the battleships of the Pacific Fleet heard the whine of aircraft engines and spotted dark specks diving toward them. What they saw and heard were F6C Hawks of Fighting VF Squadron 2 making a simulated attack, the pilots positioning their planes in steep dives as they roared down on their targets. The event marked the first fleet demonstration of the tactic of dive-bombing, and less than two months later squadrons of Aircraft Squadrons, Battle Fleet completed their first dive-bombing exercise.16

As was the case with the development of torpedo aircraft, the evolution of bomber designs during the interwar years was in part driven by the increasing weight of the ordnance, their reason for being. Yet, most of the aircraft initially filling the “light bombing” role were not employed solely in that mission, the Bureau of Aeronautics as late as 1927 issuing the opinion that there was no need for a specialized aircraft for that task alone. Four years later the air groups in Lexington and Saratoga did not even include a bombing squadron, each carrier instead embarking two fighting squadrons with one devoted to the fighting mission and one to light bombing. Even the aircraft considered the first Navy design built specifically for dive-bombing, the Curtiss F8C, was a dual mission aircraft that operated in the fleet as a fighter bomber.17

During the prewar years the fleet would never divest itself of using a multi-mission aircraft as a dive-bomber, but during the early 1930s the Bureau of Aeronautics issued requests for proposal for a new classification of aircraft called the scout-bomber to equip carrier-based scouting and bombing squadrons. This aircraft would fulfill the missions outlined in the war instructions of attacking enemy surface ships and scouting tactically.18 Among naval aircraft, the scout-bombers designed in the decade preceding World War II were among the most technologically advanced. The SBU was the first capable of exceeding 200 mph, its wings reinforced to handle the stress of steep dives carrying a 500-pound bomb, while the BF2C-1 Goshawk possessed an all-metal wing structure that made it even more durable in a dive. The SB2U Vindicator, ordered in 1934, was the sea service’s first monoplane scout-bomber. However, the greatest developments came with the Northrop BT-1 and the SBD Dauntless. The former, delivered in 1937, incorporated unique split flaps, the upper and lower flaps opening when the airplane was in a dive. When flight tests revealed extreme buffeting in the horizontal stabilizer, engineers added holes to the flaps, which remedied the problem and in dive-bombing runs slowed the aircraft and made it a stable bombing platform. This technology carried over to Douglas Aircraft Company’s SBD Dauntless, which boasted a top speed of 256 mph, could carry a 1,000-pound bomb, and had a maximum range of 1,370 miles in the scouting configuration. Enhancing the capabilities of these aircraft as dive-bombers was equipment such as telescopic sights and a bomb crutch, the ladder swinging ordnance away from the fuselage during a dive so that falling bombs did not strike the aircraft’s propeller.19

In comparison to dive-bombers and torpedo planes, fighter aircraft had a sound foundation upon which to build during the interwar years, air-to-air combat having advanced more during World War I than other arenas of air warfare. Fighters provided cover for bases and ships against enemy air attack and protected bombing and torpedo planes en route to bomb enemy targets, their missions also including clearing the skies of enemy fighters and shooting down enemy scouting planes to deny information to enemy commanders.20 In short, on the wings of fighter planes rested the responsibility of gaining control of the air and maintaining air superiority, the ideal characteristics for aircraft tasked with this mission being speed, rate of climb, and maneuverability. These characteristics were greatly enhanced in naval aircraft by the introduction of air-cooled engines, embodied by the Pratt & Whitney Wasp. Unencumbered by a radiator that was standard on water-cooled engines, the Wasp was lighter, the savings in weight translating into improved performance. Endurance tests also revealed that air-cooled engines were more reliable, which was appealing for naval aircraft that operated over open ocean far removed from land bases.21

As mentioned above, Navy fighters of the interwar era were viewed as multi-mission platforms, as evidenced by the fact that it was fighters that delivered the first successful fleet demonstration of a dive-bombing attack. The Bureau of Aeronautics, in issuing specifications to aircraft companies for the design of new fighter planes, routinely included parameters for the aircraft in the bombing role. As tactics developed during the 1920s and 1930s, however, air-minded officers came to the realization that saddling fighters with a bomb diminished their ability to provide air superiority. As Rear Admiral Harry E. Yarnell commented in 1932 during his tour as Commander, Aircraft Squadrons, Battle Force, “It is becoming increasingly evident that if the performance of fighters is to be improved . . . bombing characteristics of fighters must be made secondary to fighting characteristics.”22

Yarnell’s letter coincided with the emergence of the first fighter designed by the relatively new Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, the FF-1. Delivered in 1933, the airplane boasted features new to Navy fighters, including an enclosed cockpit canopy, an all-metal fuselage, and retractable landing gear. Though its forward fuselage was bulbous in order to house the latter, the FF-1 had a top speed of 207 mph, this attribute becoming readily apparent to a U.S. Army Air Service squadron commander, who upon seeing one of the “Fifis” during a tactical exercise over Hawaii in 1933 decided to make a run on it. “Great was his amazement when his dive upon the innocent looking target failed to close the range.”23 One other aspect of the FF-1’s design was that it was a two-seater, with room for a pilot and observer, an arrangement more in line with torpedo and bombing planes. This fact sparked a debate among fighter pilots over the direction of design of future aircraft. In a 1935 memorandum to the Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, the commanding officer of VF-5B noted the two-seat fighter’s superiority in escorting strike groups was possible because of the observer’s ability to scan the skies for enemy aircraft and proclaimed it less vulnerable to diving attack by enemy fighters for the same reason. The VF-5B skipper argued that the two-seater was equal to or superior to the single-seater in all tactical missions required of fighter aircraft. Conceding the general advantage of smaller, single-seat fighters in speed and maneuverability, he concluded that in naval warfare control of the air was obtained not by air-to-air superiority over enemy aircraft formations, but by knocking out the carriers from which the enemy planes operated. “In this the superior characteristic of the single-seater [sic] fighter can play little or no part.”24

A tactical board convened by Commander, Aircraft Squadrons, Battle Force issued a report on the issue the following January, defining a fighter plane as a “high speed weapon of destruction against other aircraft.” The board criticized the dismissal of this fundamental mission of Navy carrier fighters, writing that the VF-5B commander’s report “gives undue importance to secondary fields of employment . . . emphasizing the suitability of the airplane for a function which is not one for which a VF [fighter plane] is properly suited.” The board concluded that “present VF aircraft in service are of practically no value as VF. They lack either necessary speed superiority over other types or necessary offensive armament, or both.”25

This quest for speed would endure, with Grumman following up the FF-1 with first the F2F and then the F3F biplanes, each faster but limited in capability when compared with the Japanese A6M Zero also under development in the late 1930s (the A6M-2, which was operational in 1940, had a top speed of 331 mph compared to 264 mph for the F3F-3).26 Throughout the late 1930s the Bureau of Aeronautics initiated requests for proposals to the nation’s aircraft industry for fighter designs that emphasized speed and improved armament. In this approach of casting a wide net, the Navy received a variety of designs. Some, including the unorthodox twin-engine F5F Skyrocket, did not enter production, while others, namely Brewster’s F2A Buffalo monoplane, were put into production, but proved disappointing. The aircraft that emerged as the best that could be placed in production most quickly was Grumman’s F4F Wildcat, a monoplane successor to the company’s earlier biplane fighter designs, which with its super-charged engine achieved a maximum speed of 333.5 mph at an altitude of 21,300 feet and boasted four .50-caliber machine guns for armament. On it would rest the fortunes of Navy and Marine fighter squadrons until 1943.

The aircraft carrier and the airplanes that flew from her deck represented the cutting edge of naval aviation operations of the interwar years, with New York Times reporter Lewis R. Freeman capturing the public’s excitement over the ship’s unique operations in an article written in the aftermath of Fleet Problem IX. “Just about the most spectacular show in the world today . . . is the handling and manoevering [sic] of the great carriers Lexington and Saratoga,” he wrote. “The spectacle of launching and landing planes is fully up to the superlative scale of the ship itself. . . . In the darkness of early morning the effect is heightened by circles of spitting fire from the exhausts and the colored lights of the wings and tail.”27 However, the foundation upon which the airplane entered naval service was seaplanes and flying boats, and in the immediate postwar years they provided naval aviation’s first real integration with fleet operations.

Established in early 1919, Fleet Air Detachment, Atlantic Fleet, put to sea in exercises with surface forces, part of its operations being flights of wheeled aircraft from improvised decks on board battleships. However, significant attention was also devoted to flying boat operations and their support of surface ships, particularly in the spotting of naval gunfire. “For the first time in the history of the Navy, the actual setting of the sights was, to a large extent, controlled by the officers of the Airboat squadron,” read an air detachment report of 1920. “This marks the beginning of a new era in our naval gunnery.”28 Success in this role, the spotting of naval gunfire, led to the eventual assignment of detachments of seaplanes to cruisers and battleships as part of cruiser scouting (VCS) and observation (VO) squadrons, respectively. To fill this requirement, a number of aircraft procured by the Navy during the interwar years, including the VE-7, UO/FU, and O2U, could be operated in both the landplane and floatplane configuration. By the time the United States entered World War II, the principal aircraft flying in the scouting and observation roles were the Curtiss SOC Seagull and Vought OS2U Kingfisher, the latter a monoplane of which over a thousand were eventually produced.29

Long-range scouting would become the domain of flying boats, the detachment demonstrating their endurance in a lengthy seven-month cruise with the fleet, logging 12,731 nautical miles, some 4,000 of which were in direct maneuvers with the fleet. Meanwhile, in the Pacific, flying boats and seaplane tenders formed Air Force, Pacific Fleet in July 1920, putting to sea for joint fleet exercises that demonstrated the scouting capabilities of Navy flying boats. During the cruise, wartime F-5L flying boats covered a distance of 6,076 miles in operations between California and Central America. Wrote Admiral Hugh Rodman, Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, at the conclusion of the exercises, “The scouting work performed by the seaplanes was carried out to a distance of about one hundred and sixty-five miles from the bases and in weather which, except under war conditions, might have caused the commander of the force to hesitate about sending the planes into the air.”30

During the late 1920s flying boat operations in the Navy began to stagnate as increasing emphasis and funding was devoted to aircraft carrier development. Though over the course of the ensuing years new designs appeared, they were, in the words of Rear Admiral A. W. Johnson in a paper on the development and use of patrol planes, “of no useful purpose except for training and utility services.”31 In contrast to the seagoing force that had demonstrated so much the potential of the flying boat in fleet operations in the immediate postwar years, Johnson, who commanded Aircraft, Base Force, noted that “patrol plane squadrons became in reality a shore based force,” with cruising reports of seaplane tenders during the late 1920s and early 1930s proof of the diminished employment of flying boats in fleet operations.32 Even the Consolidated Aircraft Company’s P2Y, which achieved fame when it equipped Patrol VP Squadron 10F in a record-setting non-stop flight between California and Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, in January 1934, had limitations: “[It] must operate from sheltered harbors, and can do nothing in the way of scouting and bombing that cannot be as equally well done by large land planes operating from established shore bases equipped with good flying fields.”33 Yet, landplanes for distant overwater flights were the exclusive domain of the Army Air Corps, a 1931 agreement between Army Chief of Staff General Douglas MacArthur and Chief of Naval Operations Admiral William V. Pratt preventing the Navy from operating long-range land-based aircraft.34

Johnson’s comments came at a critical juncture for both the development of flying boats and the strategic requirements for their employment in the event of war. By the early 1930s, those officers working on War Plan Orange, the constantly evolving American strategy in the event of war with Japan, had begun to more appreciate the role of air power in a fleet engagement. With ships able to engage at greater distances, advance scouting, particularly in the open expanses of the Central Pacific, could prove a deciding factor between victory and defeat.35 For proponents of patrol aviation, this tactical and strategic requirement for flying boats coincided with the introduction of a plane that represented a tremendous advance in flying boat technology—the PBY Catalina.

With a maze of struts and wires between wings limiting the performance of earlier biplane designs, Consolidated Aircraft Company engineers drew up a flying boat built around a high-mounted parasol wing with minimal struts necessary because of internal bracing; this reduced drag, as did wing floats that retracted once airborne to form wingtips. Despite a gross weight that exceeded that of the P2Y it replaced, the PBY boasted a top speed nearly 40 miles per hour faster than that of the P2Y. Deliveries of the PBY began in 1936, and two years later fourteen Navy patrol squadrons operated the type.36 “I feel very strongly that when the PBY’s [sic] come into service, the Fleet will begin to realize the potentialities of VP’s [sic] [patrol planes],” wrote Rear Admiral Ernest J. King on the eve of the aircraft’s delivery, “and will begin to demand their services.”37

Performance in fleet exercises validated the PBY’s capabilities as a long-range scout. Comments on patrol plane activities in Fleet Problem XVIII held in early 1937 concluded that they were capable of locating an enemy force within a five hundred- to one thousand-mile radius of their bases, night tracking, and high-altitude bombing.38 “Your patrol planes have certainly changed the whole picture in regard to tactics and even strategy,” Captain W. R. Furlong of the Bureau of Ordnance wrote King. Such was the range that the newly arrived Catalinas could reach; planners of future war games would have to “put the brakes on the patrol planes to keep them from finding out everything long before we could get the information from the cruisers and other scouts.”39

The capabilities of the PBY, coupled with fatal crashes, spelled the end of the use of rigid airships as long-range scouts, an idea long championed by Rear Admiral William A. Moffett, the first chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics. However, non-rigid airships, notably of the K-class would prove effective in long-range antisubmarine patrols during World War II.40

Not as clear in discussions about patrol aviation was the advisability of using flying boats in a bombing role. There was indeed a precedent in the practice, F-5Ls having participated in the famous 1921 bombing tests against captured German warships and stricken U.S. Navy vessels.41 In 1934, while serving as Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, Rear Admiral Ernest J. King had suggested that flying boats could serve as a first strike weapon in an engagement at sea, their attacks preceding those of carrier planes and surface forces.42 Correspondence between Captain John Hoover and Admiral Joseph Mason Reeves, the latter Commander in Chief, United States Fleet, the following year illuminated the problems with flying boats operating in this capacity. Umpires in fleet exercises determined that patrol planes would incur heavy losses and inflict insignificant damage to capital ships when used in the strike role, with Hoover pointing to the fact that the slow speeds and low service ceilings of patrol planes then in operation (the Consolidated P2Y and Martin PM) made attacks by them “suicidal.” “The way to utilize patrol planes for attacking must by re-studied from a practical viewpoint.”43 The introduction of the PBY Catalina (“PB” being the Navy designation for patrol bomber), which incorporated a nose compartment for a bombardier and provision to carry the Norden bombsight, offered more promise when it came to patrol bombing operations. However, as the author of the foremost study of planning for the war against Japan has noted, by 1940 the notion of operating flying boats as patrol bombers had been discounted.44 Yet, wartime necessity would awaken interest in flying boat offensive operations for the PBY and other flying boat designs of the 1930s, including the PBM Mariner and PB2Y Coronado.

By mid-1941, the year in which naval aviation entered the world’s second global war, the Secretary of the Navy could report a net increase of 82 percent over the previous fiscal year in the number of service aircraft on hand in the Navy’s inventory. His annual report noted emphasis being placed on development of dive-bombing and fighting aircraft of greater power, which was “vindicated in the service reports received from belligerents abroad.”45 Other technical adaptations based on wartime observations included such equipment as self-sealing fuel tanks and improved armor and firepower. “With the present international situation,” the secretary concluded, “it is imperative that all construction work on ships, aircraft and bases be kept at the highest possible tempo in order that the prospective two-ocean Navy become a reality at the earliest possible date.”46 The sudden events of the morning of 7 December 1941 shifted this tempo into previously unimagined levels, the events that occurred between that day and September 1945 representing the ultimate test for the technology and tactics that evolved during the previous two decades.

“When war comes,” Captain John Hoover wrote in 1935, “we will have just what is on hand at the time, not planes on the drafting board or projected.”47 For naval aviation, the combat aircraft flying from carrier decks, fleet anchorages, and airfields when war came had entered service between 1936 and 1940. Fortunately, however, the planes that eventually would replace or complement them were far removed from the drafting board. The prototype of the F6F Hellcat made its first flight just months after the Pearl Harbor attack, while the XF4U-1 Corsair had already demonstrated speeds of over four hundred mph during test flights in 1940. Similarly, prototypes of the SB2C Helldiver and TBF Avenger had already taken to the air by the time the United States entered World War II. And with the coming of war, the mobilization of industry translated into rapid transformation of prototypes into production versions of airplanes ready for combat, with American factories turning out an average of 170 airplanes per day from 1942 to 1945.48

How did these airplanes fare in the crucible of combat? A telling statistic is found in an examination of air-to-air combat: During the period 1 September 1944–15 August 1945, the zenith of naval aviation power in the Pacific, in engagements with enemy aircraft, a total of 218 naval carrier–based and land-based fighters were lost in aerial combat, while Navy and Marine Corps FM Wildcat, F6F Hellcat, and F4U Corsair fighters destroyed 4,937 enemy fighters and bombers.49 Even during the period 1942–1943, when naval aviators flew the F4F Wildcat, which in comparison to the heralded Japanese Zero had an advantage only in its defensive armor and self-sealing fuel tanks, carrier-based and land-based Wildcat pilots splashed 905 enemy fighters and bombers. This came at a cost of 178 Wildcats destroyed and 83 damaged.50 Comparing the two eras, in all the action sorties flown by naval aircraft during 1942, 5 percent ended in the loss of the aircraft. In 1945, less than one-eighth of 1 percent of all action sorties resulted in a combat loss.51 While direct comparisons are not possible with other classes of aircraft, a look at the total number of sorties flown against land and ship targets by year is revealing. In the first two years of the war, 19,701 sorties were directed against ship and shore, a figure that for the years 1944–1945 jumped to 239,386!52

A key reason for this increase was aircraft development. The carrier Enterprise (CV-6), at sea when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, had none of the same aircraft types on board when she operated off Japan in 1945. The F4U Corsair and F6F Hellcat by that time in the war boasted better top speeds, rate of climb, and performance at altitude than the most advanced versions of the Japanese navy’s Zero fighter. Similarly, the SB2C Helldiver and TBF/TBM Avenger, particularly once technical maladies were corrected in the former, proved to be more than comparable to the aircraft operated by the Japanese in the torpedo and bombing roles. In addition, Japanese aircraft to a great extent suffered from deficiencies in their armor protection, making them more susceptible to being shot down by Allied aircraft and antiaircraft gunners. Even though the Japanese did produce some very capable aircraft as the war progressed—among them the all-metal Yokosuka D4Y Suisei bomber that had a top speed comparable to many fighters and the Kawanishi N1K1-J/N1K5-J Shiden and Shiden Kai fighter, which in the hands of an experienced pilot could be more than a match for an Allied fighter—they appeared in too few numbers to have much effect on the outcome of the war. In addition, due to increasing Allied superiority in material, the successful campaign against Japanese merchant and combat ships, and the increasing conquest of territory, Japanese planes were at a strategic and tactical disadvantage before they even left the ground.53

There is more to the story behind the statistics. First, sortie rates and the number of enemy aircraft destroyed rose in direct proportion to the growth of U.S. naval aviation. In 1941 there were 1,774 combat aircraft on hand in the U.S. Navy. By 1945 that figure had grown to 29,125.54 When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the Navy had a total of seven fleet carriers and one escort carrier in commission. Between that time and the end of the war, the Navy commissioned 102 flattops of all classes.55 Then there was the human factor. Imperial Japanese Navy and Army pilots generally remained in combat squadrons until they were killed or suffered wounds that rendered them unable to fly, this policy of attrition steadily reducing the quality of enemy pilots faced as the war progressed. This was apparent as early as late 1942, a Report of Action of Fighting Squadron (VF) 10 in November 1942 noting that the “ability of the enemy VF [fighter] pilots encountered in the vicinity of Guadalcanal is considered to be much inferior to the pilots encountered earlier in the war.”56 In contrast, experienced U.S. naval aviators rotated in and out of combat squadrons. For example, Lieutenant Tom Provost, designated a naval aviator during the late 1930s, flew fighting planes from the carrier Enterprise (CV-6) during the early months of World War II, including service at the Battle of Midway. His next tour was as a flight instructor, imparting knowledge to fledgling pilots before returning to the fleet in 1944 and 1945 to fly F6F Hellcat fighters off an Essex-class carrier.57 These naval aviators were well led and well trained. Fighter squadron commanders during the early months of the war, notably Lieutenant Commanders John S. Thach and James Flatley, proved adept at developing tactics to maximize the advantages of their aircraft over those of the enemy while the U.S. Navy’s longtime emphasis on teaching deflection shooting paid dividends in actual combat.58 The same imparting of lessons learned was standard in other types of squadrons as tactics developed throughout the war.

During World War II, were U.S. Navy aircraft employed in a manner envisioned during the interwar years and how did the ever-changing tactical environment affect the operations of naval aircraft? The answers to these questions provide an important framework in which to assess the history of aircraft development between 1922 and 1945.

Much prewar discussion centered on how naval aircraft could be most effective in a fleet engagement, and concerns expressed at that time about the vulnerability of torpedo planes proved well founded, with carrier-based torpedo squadrons at Midway suffering grievous losses. Despite the fact that even as late as May 1945, experienced carrier task force commander Vice Admiral Marc A. Mitscher still considered the torpedo “the major weapon for use against surface ships,” the number of torpedoes dropped at sea decreased as the war progressed.59 For carrier-based aircraft and land-based aircraft, during the first year of the war torpedoes accounted for 73 percent and 94 percent, respectively, of the total ordnance expended on shipping by weight. By 1945, those figures had dropped to 16 percent and 0 percent, respectively, and throughout the war only 1,460 torpedoes were dropped by naval aircraft.60 Factors contributing to these low numbers included the problematic aerial torpedoes in the U.S. inventory early in the war and the focus of carrier strikes in the war’s latter months being increasingly centered on hitting land targets. During 1945 the total tonnage of bombs dropped on land targets by Navy and Marine Corps aircraft was 41,555 as compared to just 4,261 tons of ordnance dropped on ships of all types during the same period.61

Dive-bombing lived up to expectations as a tactic that could influence the outcome of a sea battle, a fact demonstrated in dramatic fashion in the sinking of four Japanese carriers at the Battle of Midway. However, as evidenced by the statistic above, as the war moved ever closer to the Japanese home islands, targets for carrier-based dive-bombers were increasingly located ashore rather than afloat, with planes attacking harbor areas, transportation networks, and enemy airfields. It was in the bombing mission that wartime experience shuffled the prewar and early war composition of carrier air groups. Scouting squadrons, which in 1942 were equipped with the same airplane—the SBD Dauntless—as bombing squadrons on board carriers, were eliminated from carrier air groups by 1943. In addition, torpedo planes and fighters increasingly assumed some of the ground attack mission, the latter reawakening the fighter versus fighter bomber debate of the 1930s. Commanders had no choice but to use fighters in the bombing role during 1944 and 1945 when the advent of the kamikazes necessitated that the number of fighter planes in a carrier air group be increased dramatically. By war’s end, their numbers were double that of the combined number of torpedo and scout-bombers.62 In the fighter-bomber role, naval single-engine fighters from land and ship logged a comparable number of ground attack missions as that of airplanes designed as bombers. However, on these missions they expended primarily rockets and machine gun ammunition.63 The SBD Dauntless, SB2C Helldiver, and TBF/TBM Avenger proved the mainstay of the bombing mission, the latter aircraft proving to be one of the most versatile naval aircraft of the entire war. The dive-bombers carried 34 percent of all naval aviation’s bomb tonnage, while Avengers delivered 32 percent of the bomb tonnage and launched 29 percent of all rockets.64

U.S. Navy Curtiss SB2C Helldiver returns from a strike on Japanese shipping.

The employment of fighters in the bombing role was central to the debate about the composition of carrier air groups, the subject of much discussion as the war drew to a close. A 1944 survey of carrier division commanders on the subject revealed a consensus that the majority of airplanes on deck should be fighters, the problematic SB2C Helldiver perhaps influencing calls for fighters to assume a ground attack role in addition to the air-to-air mission. Vice Admiral Mitscher preferred dive-bombers over fighter bombers, telling Captain Seldon Spangler, who was on an inspection tour of the Pacific in 1945, that dive-bombers, even given the inadequacies of the SB2C, were better than the F4U Corsair in the bombing role. Wrote Spangler, “He thought it would be most desirable to get down to two airplane types aboard carriers, one to be the best fighter we can build, the other to be a high performance torpedo dive bomber.” Rear Admiral Gerald F. Bogan concurred to some degree. Although favoring the intensification of dive-bombing for fighting planes, he wrote “Do not emasculate the VF plane.”65 Interestingly, in production were two airframes that met Mitscher’s requirements, the BT2D (later AD) Skyraider, which combined the torpedo and bombing missions into one attack mission, and a pure fighter in the form of the F8F Bearcat. Interestingly, the F4U Corsair, which, after some technical problems were solved, became an excellent carrier plane and served for years after World War II on the basis of its capabilities as a fighter bomber.

“The Fleet is well satisfied with PBY-5A airplanes for use at Guadalcanal for night reconnaissance, bombing, torpedo attack, mining, etc.,” read an 28 April 1943, report to the Director of Material in the Bureau of Aeronautics. “They are not using these airplanes in the daytime except in bad visibility.”66 This concise summary of operations in the first part of the Pacific War reveals that in their decision to remove the flying boat from consideration as a long-range daylight bomber, prewar officers were correct about the platform’s capabilities. Action in the war’s early weeks proved the vulnerability of the lumbering PBYs to enemy fighters, with four of six PBYs of VP Patrol Squadron 101 shot down on a 27 December 1941, raid on Jolo in the central Philippines.67 However, under the cover of darkness, the aircraft proved highly effective in the ground attack mission. As prewar exercises demonstrated, PBYs performed well as long-range scouts, most notably in their locating elements of the Japanese fleet at Midway. Their ability to patrol wide expanses of ocean also made them effective as antisubmarine platforms against German U-boats as well as very capable search and rescue aircraft.68

What could not have been foreseen during the 1930s in light of the division of roles and missions between the armed services was the successful operation of long-range multi-engine landplanes in naval aviation. As noted above, the Pratt-MacArthur agreement had given the Army Air Corps exclusive use of long-range land-based bombers to fill their role in coast defense, but with flying boats limited in daylight bombing, the Navy began pressing for the ability to operate multi-engine bombers from land bases. In July 1942 the Sea Service reached an agreement with the Army Air Forces (re-designation of Army Air Corps in 1941) to divert some production B-24 Liberators to the Navy for use as patrol bombers. The first of these airplanes, designated PB4Y- 1s, were delivered to the Navy in August, and the following year, with its focus on the strategic bombing campaigns in Europe and the Pacific, the Army Air Forces relinquished its role in antisubmarine warfare. Other aircraft eventually joined the PB4Y-1 in the patrol bombing role in both the European and Pacific theaters, including a modified Liberator designated the PB4Y-2 Privateer, the PBJ (Army Air Forces B-25) Mitchell, and the PV Ventura/Harpoon.69

While the Army Air Forces employed their bombers in primarily in horizontal attacks, which were also carried out by Navy and Marine Corps medium bombers, many Navy crews specialized in low-level bombing, oftentimes dropping on enemy shipping at masthead level. A review of 870 PB4Y attacks against shipping revealed that over 40 percent of them resulted in hits. In addition, they were credited with downing over three hundred enemy planes, the PB4Ys being heavily armed with machine guns. Marine PBJs proved the workhorse of land-based patrol bombers, flying more than half of all action sorties flown. All told, patrol bombers, while flying just 6 percent of naval aviation’s action sorties, dropped 12 percent of all bomb tonnage delivered on targets during World War II.70

A number of other operations involving naval aircraft are worthy of discussion in drawing conclusions about the development of naval aircraft through World War II. Radar-equipped aircraft made tremendous strides in operations after dark during World War II, completing some 5,800 action sorties from carriers and land bases. From a total of only 76 attacks (air-to-ground and air-to-air) against enemy targets in 1942, naval aviation night operations grew to include 2,654 nocturnal attacks in 1944. The PBYs would not have been able to have as much of an offensive impact as they did without their night attack capability.71 Carrier aircraft, despite fears about tying carriers to beachheads in support of amphibious operations, achieved a great deal of success in providing close air support to assault forces, primarily flying from escort carriers. Naval aircraft, including carrier-based ones, proved that they could neutralize land-based air power, with fighter sweeps focusing on enemy airfields on island chains and the Japanese homeland serving the purpose of striking potential attackers at their source. “Pilots must be impressed with the double profit feature of destruction of enemy aircraft,” read a June 1945 memorandum on target selection for Task Force 38 carriers operating off Japan. “Pilots must understand the principles involved in executing a blanket attack. The Blanket Operation is NOT a defensive assignment. It is a strike against air strength.”72 Finally, in the field of weapons development, the advances like electronic countermeasures equipment to thwart enemy radar and the introduction of high-velocity aircraft rockets (HVAR) made carrier aircraft more capable platforms, the latter yielding positive results particularly in close air support against enemy defensive positions.73

In a speech delivered during the 1920s, Admiral William S. Sims remarked, “One of the outstanding lessons of the overseas problems played each year is that to advance in a hostile zone, the fleet must carry with it an air force that will assure, beyond a doubt, command of the air. This means not only superiority to enemy fleet aircraft, but also to his fleet and shore-based aircraft combined.”74 This statement reflected the essence of naval air power, and it can be argued that during the interwar years all aspects of aircraft development, from design to tactics, supported the drive of naval aviation advocates toward a fleet that reflected this vision. By 1945, at the end of the greatest war the world has ever known, a triumphant flight of hundreds of carrier planes over the battleship Missouri (BB 63) as the instrument of surrender was being signed on her deck was proof that the vision had been realized.

1. Lieutenant Austin K. Doyle to Mrs. Jamie R. Doyle, 13 February 1929 (Admiral Austin K. Doyle Papers, Emil Buehler Naval Aviation Library, National Naval Aviation Museum (hereafter cited as Doyle Papers).

2. Doyle graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1919 as a member of the class of 1920, his graduation date moved up because of World War I. He commanded two carriers, Nassau (ACV-16) and Hornet (CV-12), during World War II.

3. Roy Grossnick, ed., U.S. Naval Aviation, 1910–1995 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1995), p. 37.

4. Peter M. Bowers, Curtiss Aircraft, 1907–1947 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1987), pp. 74–75; Clark G. Reynolds, Admiral John H. Towers: The Struggle for Naval Air Supremacy (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1991), pp. 99, 117.

5. Charles M. Melhorn, Two-Block Fox: The Rise of the Aircraft Carrier, 1911–1929 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1974), pp. 27–30, 37; Grossnick, U.S. Naval Aviation, p. 38.

6. Lieutenant Commander Henry C. Mustin to his wife, 23 January 1914 (Captain Henry C. Mustin Papers, Emil Buehler Naval Aviation Library, National Naval Aviation Museum).

7. Grossnick, U.S. Naval Aviation, pp. 505–6.

8. Melhorn, Two-Block Fox, pp. 37–38.

9. “Tactics,” Thesis submitted by Commander Patrick N. L. Bellinger as a member of the class of 1926 at the U.S. Naval War College (copy in Emil Buehler Naval Aviation Library, National Naval Aviation Museum).

10. War Instructions, United States Navy, 1934 (copy in Emil Buehler Naval Aviation Library, National Naval Aviation Museum).

11. Norman Friedman, U.S. Naval Weapons (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1982), p. 186; Grossnick, U.S. Naval Aviation, p. 31.

12. René J. Francillon, McDonnell Douglas Aircraft since 1920, vol. 1 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1988), pp. 46–52.

13. Thomas Wildenberg, Destined for Glory: Dive Bombing, Midway, and the Evolution of Carrier Airpower (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1998), pp. 104–7; “Aircraft Tactics—Development of,” Aircraft Squadrons, Battle Fleet, 3 February 1927 (copy in Emil Buehler Naval Aviation Library, National Naval Aviation Museum); Friedman, U.S. Naval Weapons, p. 116.

14. Wildenberg, Destined for Glory, p. 167; Barrett Tillman, “Douglas TBD: The Maligned Warrior,” The Hook (August 1990), pp. 18–22.

15. Grossnick, U.S. Naval Aviation, p. 49; “The Naval Air Service,” A lecture delivered at the Army War College by Rear Admiral William A. Moffett, Chief, Bureau of Aeronautics, 10 November 1925 (copy in Emil Buehler Naval Aviation Library, National Naval Aviation Museum).

16. Grossnick, U.S. Naval Aviation, pp. 65–66.

17. Friedman, U.S. Naval Weapons, p. 190; “Organization of Naval Aviation Battle Fleet, Aircraft Squadrons, Battle Fleet, 1931” (copy in Emil Buehler Naval Aviation Library, National Naval Aviation Museum); Bowers, Curtiss Aircraft, pp. 205.

18. War Instructions, United States Navy, 1934.

19. Gordon Swanborough and Peter M. Bowers, United States Navy Aircraft since 1911 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1990), pp. 443–46; Wildenberg, Destined for Glory, pp. 136–37; Bowers, Curtiss Aircraft, p. 264; Friedman, U.S. Naval Weapons, p. 190.

20. Moffett, “The Naval Air Service.”

21. The Pratt & Whitney Aircraft Story (Hartford: Pratt & Whitney Aircraft Division of United Aircraft Corporation, 1950), pp. 49–51.

22. Quoted in Wildenberg, Destined for Glory, p. 114.

23. Swanborough and Bowers, United States Navy Aircraft, pp. 212–13, quoted in Bureau of Aeronautics Newsletter (1 March 1933).

24. Commanding Officer, VF-5B, to Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, 22 May 1935 (copy in Doyle Papers).

25. Aircraft Tactical Board, Aircraft, Battle Force to Commander, Aircraft Battle Force, 21 January 1936 (Doyle Papers).

26. Swanborough and Bowers, United States Navy Aircraft, pp. 217–18; René Francillon, Japanese Aircraft of the Pacific War (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1990), p. 377.

27. New York Times, 10 February 1929.

28. Grossnick, U.S. Naval Aviation, p. 38; Commander Air Detachment to Air Detachment, 28 June 1920 (William W. Townsley Papers, Emil Buehler Naval Aviation Library, National Naval Aviation Museum).

29. Swanborough and Bowers, United States Navy Aircraft, pp. 428–48.

30. Grossnick, U.S. Naval Aviation, p. 48; Reynolds, Admiral John H. Towers, 174–76; Admiral Hugh Rodman to Captain Henry C. Mustin, 9 October 1920 (Correspondence File, 1917–1920, Box 2, Henry C. Mustin Paper, Library of Congress).

31. Rear Admiral A. W. Johnson, The Naval Patrol Plane: Its Development and Use of the Navy, 1935 (copy in Kenneth Whiting Papers, Nimitz Library, United States Naval Academy).

32. Ibid.

33. Grossnick, U.S. Naval Aviation, p. 86.

34. Edward S. Miller, War Plan Orange: The U.S. Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897–1945 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1991), pp. 175–76.

35. Ibid.

36. Swanborough and Bowers, United States Navy Aircraft, pp. 95–96.

37. Rear Admiral Ernest J. King to Rear Admiral Arthur B. Cook, 21 July 1936 (Correspondence File-Arthur B. Cook, Box 5, Ernest J. King Papers, Library of Congress).

38. Commander Aircraft, Base Force to Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet, 1 June 1937 (Memoranda File, 1936–1937, Box 4, Ernest J. King Papers, Library of Congress).

39. Captain William R. Furlong to Rear Admiral Ernest J. King, 4 September 1937 (Correspondence Files E–F, 1936–1938, Box 5, Ernest J. King Papers, Library of Congress).

40. Miller, War Plan Orange, p. 176.

41. Grossnick, U.S. Naval Aviation, p. 49. These tests were more famous for the publicity garnered by Army bombers that supported General William Mitchell’s efforts to form an independent air service.

42. Bureau of Aeronautics Memorandum, 13 December 1934 (Correspondence H-R, 1933–1936, Box 4, Ernest J. King Papers, Library of Congress).

43. Admiral Joseph M. Reeves to Captain John H. Hoover, 9 April 1935 (Correspondence Files H, 1936–1938, Box 5, Ernest J. King Papers, Library of Congress); and Captain John H. Hoover to Admiral Joseph M. Reeves, 10 January 1935 (Correspondence Files R, 1936–1938, Box 6, Ernest J. King Papers, Library of Congress).

44. Miller, War Plan Orange, p. 179.

45. Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy for the Fiscal Year 1941 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1941).

46. Ibid.

47. Captain John Hoover to Admiral Joseph M. Reeves, 10 January 1935 (Correspondence Files R, 1936–1938, Box 6, Ernest J. King Papers, Library of Congress).

48. See entries in Swanborough and Bowers, United States Navy Aircraft, for respective aircraft; Barrett Tillman, “Cost of Doing Business,” Flight Journal, Vol. 14, No. 6 (December 2009), p. 31.

49. Statistical Information on World War II Carrier Experience: Special Study-Aircraft Performance Characteristics (copy in Emil Buehler Naval Aviation Library, National Naval Aviation Museum).

50. Naval Aviation Combat Statistics—World War II (Washington, DC: Air Branch, Officer of Naval Intelligence, Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, 1946), p. 60.

51. Ibid.

52. Ibid., p. 84.

53. Mark R. Peattie, Sunburst: The Rise of Japanese Naval Air Power, 1909–1941 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2001), pp. 183, 187; René Francillon, Japanese Aircraft of the Pacific War (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1990), pp. 454–61, 320–29; Statistical Information on World War II Carrier Experience: Special Study-Aircraft Performance Characteristics (copy in Emil Buehler Naval Aviation Library, National Naval Aviation Museum).

54. Grossnick, U.S. Naval Aviation, p. 448.

55. Ibid., pp. 423–31.

56. Commander, Fighting Squadron Ten to Commanding Officer, USS Enterprise, Report of Action—10–17 November 1942 (copy in files of Emil Buehler Naval Aviation Library, National Naval Aviation Museum).

57. Clark G. Reynolds, The Fast Carriers, 2nd edition (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1992), p. 62; Papers of Thomas Provost (Emil Buehler Naval Aviation Library, National Naval Aviation Museum).

58. John B. Lundstrom, The First Team: Pacific Naval Air Combat from Pearl Harbor to Midway (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1984), pp. 458–68.

59. Captain Seldon B. Spangler to Chief, Bureau of Aeronautics, Report on Trip to Pacific Area, 5 May 1945 (Vice Admiral Seldon B. Spangler Papers, Emil Buehler Naval Aviation Library, National Naval Aviation Museum).

60. Naval Aviation Combat Statistics—World War II, pp. 112–13.

61. Ibid., p. 109.

62. Reynolds, The Fast Carriers, p. 357.

63. Naval Aviation Combat Statistic—World War II, p. 102.

64. Ibid.

65. Captain Seldon B. Spangler to Chief, Bureau of Aeronautics, Report on Trip to Pacific Area, 5 May 1945 (Vice Admiral Seldon B. Spangler Papers, Emil Buehler Naval Aviation Library, National Naval Aviation Museum); Commander William N. Leonard to Vice Admiral John S. McCain, circa 1944 (copy in John S. Thach Papers, Emil Buehler Naval Aviation Library, National Naval Aviation Museum).

66. Commander Seldon B. Spangler to Director of Material, Bureau of Aeronautics, Comments on Various Airplanes (Vice Admiral Seldon B. Spangler Papers, Emil Buehler Naval Aviation Library, National Naval Aviation Museum).

67. Michael D. Roberts, Dictionary of American Naval Aviation Squadrons, vol. 2 (Washington, DC: Naval Historical Center, 2000), p. 443.

68. See Captain Richard C. Knott, The American Flying Boat: An Illustrated History (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1979).

69. Swanborough and Bowers, United States Navy Aircraft, p. 103.

70. Naval Aviation Combat Statistics—World War II, pp. 15, 124.

71. Ibid., pp. 119–20.

72. Miller, War Plan Orange, p. 350; Commander, Task Force 38 to Task Force 38, 26 June 1945, Selection of Japanese Targets for Carrier Based Attack (copy in John S. Thach Papers, Emil Buehler Naval Aviation Library, National Naval Aviation Museum).

73. For HVAR use, see Naval Aviation Combat Statistics—World War II, pp. 33–35.

74. In Chronological Section, 1904–1921, Rear Admiral William A. Moffett Papers (Microfilm copy in Nimitz Library, U.S. Naval Academy).