“My Africa, Motherland of

the Negro peoples!”

In May 1935 the Baltimore Afro American reported on a parade in Harlem, New York. Two thousand people marched to the Abyssinian Baptist Church in protest of Italy’s invasion of Abyssinia (later Ethiopia). The crowd congregated in the church to listen to a series of speakers read poems, press for a boycott of Italian American businesses, and urge support for Ethiopia and its citizens. I. Alleyn of the Workers Forum passionately declared that “when a man in Abyssinia is struck by Italy, it is not that one man alone who is hurt, but men in the British West Indies, in America, and in every country where black men are found.” Men and women of African descent around the world were outraged by Italy’s aggression against Abyssinia.1

Alleyn voiced a sentiment shared by many of those crowded in the church that day—that black America and Africa were intimately connected, largely because of the color of their skin. African Americans saw their plight as inextricably linked with that of Africans and their struggle for liberation. This belief was sustained until Africans gained independence from colonial rule.

From the 1930s to the 1950s African Americans agitated, advocated, and spoke out on behalf of Africa and its people. During the Cold War, as the United States began to see the continent’s importance, African Americans played a leading role in the new relationship between Africa and the United States. In this era we can see clear distinctions between African American interest, identification, influence, and engagement with Africa. There were those who continued to identify with Africa as a source of their heritage and those who sought to influence events on the continent, advocate on its behalf, and help shape American policy toward it. As descendants of Africa they frequently crafted a discourse positing themselves as suitable consultants and advisers on African issues. However, by the middle of the twentieth century the voice for Africa in the United States was no longer solely an African American voice. Africans were speaking for themselves.

By the early twentieth century European colonizers had consolidated their hold in Africa. Colonialism was characterized by a racial domination similar to that which existed in the United States. Strong elements of racism, cultural imposition, and economic exploitation marked the relationship between European colonizers and their African subjects. The historian Christopher Fyfe has written cogently on racial rule in Africa, pointing out the use of race as “political control.” “Authority in colonial Africa,” he observes, “was white authority, exercised through the presence of an imputed white skin.”2

Although Africans were a majority in the colonies, they were subordinated and their resources exploited under the guise of European superiority. African subjects had very limited access to education, although missionaries often set up schools to educate them in the ways of Christianity. Consequently, there was a small literate African population in many colonies. Mostly male, literate Africans had acquired at least a secondary school education, which allowed them to hold minor positions within colonial structures. But there were few secondary schools in colonial Africa before the First World War, leaving many colonies without qualified and skilled workers. White rule was firmly established in African colonies, excluding Africans from more than clerical positions. With some exceptions, Europeans were typically hired to hold certain positions within colonial governments. Hard to attract, these people were expensive, induced to come to Africa with the promise of high salaries, subsidized housing, and frequent leave and opportunities to travel. The few Africans qualified to hold these positions resented their marginalization and began to push for change. The 1920s saw colonial governments put more emphasis on education, and by the 1930s they recognized the need for higher education of colonial subjects. Those Africans who could not wait for these developments often made their way to Europe and the United States to gain an education.3

The period between the two world wars was the beginning of a nascent nationalism in African colonies. In the 1920s and 1930s local organizations for self-help and improvement were formed in African colonies to protest colonial injustices and inequities. A newly educated class of Africans found work as interpreters, clerks, clergy, teachers, and businessmen. This group would launch an early form of nationalism. Early African nationalists, while not seriously questioning the colonial project or pushing for an end to colonial rule, nevertheless questioned European disregard for their achievements. They were gradualists who used a moderate rhetoric, asking not for an end to imperial rule but for inclusion in the running of their societies, for injustices to be redressed, and for the abuses of colonial rule to stop. Typically, these men had been educated in missionary schools, in colonial metropoles, or in the United States. They were cosmopolitan and inter-regional in their views and values. This educated elite often identified as British or French Africans rather than as members of a tribe or a particular ethnicity. Pan-Africanist in their outlook, they were often the direct products of the colonial system. Many of them took Western names, wore European clothing, and emulated their colonial masters in other ways. Those educated in the United States drew on their American experiences to craft their anticolonial language and strategies. Those who returned to Africa became examples of how to engage their colonial rulers and succeeded in effecting change.4

The Italian invasion of Ethiopia angered women and men of African descent throughout the world. As one of only two independent nations in Africa, Ethiopia “represented a potent symbol of African defiance in the face of imperialism and of a renascent Africa.”5 Although Liberia remained independent, its close relationship with the United States made it, to all intents and purposes, if not a colony, then very dependent on the larger nation. Furthermore, in the late 1920s a damning report implicated Americo-Liberian settlers in the use of indigenous Africans as forced labor on rubber plantations and accused them of participating in what was tantamount to slavery by shipping Africans to the Spanish island of Fernando Pó. These accusations soured African American attitudes toward that nation.6

Abyssinia, on the other hand, was a Christian kingdom dating back centuries, governed by Africans, and jealous of its sovereignty. African Americans could take pride in the fact that Ethiopia did not fit the typical European stereotype of savage Africa. Italy had long tried to colonize the kingdom but failed in the face of African resistance. Early in 1896 the Ethiopians had fought off Italian attempts to annex their territory. Haile Selassie’s coronation as emperor in 1930 also caught the attention of blacks around the world as they watched an African crowned the head of a self-governing African empire.7 When Italy invaded Abyssinia once again, Africans and African Americans spoke out against this affront to the nation’s sovereignty.

The African American press reported extensively on the ensuing war between Italy and Ethiopia. Activists organized demonstrations and protest marches such as the one in Harlem. All over the country organizations helped raise funds for the Ethiopian cause. The Pan-African Reconstruction Association, the International African Progressive Association, the Detroit Committee for the Aid of Ethiopia, and the Association for Ethiopian Independence all raised money. Rallies were organized by groups like the Negro World Alliance in Chicago, the Provisional Committee for the Defense of Ethiopia in New York, and the Ethiopian Relief League in Miami. Black leaders and academics like Ralph Bunche and Leo Hansberry of Howard University formed the Ethiopian Research Council in 1934; the Medical Committee for the Defense of Ethiopia sent medical supplies to the African nation.

Black Americans boycotted Italian American businesses and individuals volunteered to fight in the Ethiopian army. Hubert Julian and John Robinson served as pilots for Emperor Haile Selassie, who years later would acknowledge the contributions of African Americans: “We can never forget the help Ethiopia received from Negro Americans during the crisis. . . . It moved me to know that Americans of African descent did not abandon their embattled brothers, but stood by us.”8

At the same time that African Americans spoke out against European occupation of Africa, they pushed for changes within their own communities. Many began to understand their experience in broader and more global terms, seeing parallels between their situation and that of African-descended people worldwide. Black Americans connected Ethiopia’s plight with that of the larger African world, and many saw a direct correlation between their situation and events in Ethiopia. An extract from the Daily Worker illustrates how some black Americans understood this act of aggression. A strongly worded editorial declared that “the struggle against the projected rape of Abyssinia is inextricably linked with the fight against war and fascism for Negro liberation, for the national independence of the peoples of Africa and the West Indies, for unconditional equality of the Negro people everywhere and for self-determination for the Negro majorities in the Southern Black Belt territories of the United States.” The NAACP weighed in, noting, “When all is said and done, the struggles of the Abyssinians is fundamentally a part of the struggle of the black race the world over for national freedom, economic, political and racial emancipation.”9

African Americans from all walks of life spoke out against Italy’s aggression even as they faced similar assaults at home. The enthusiastic response and support of black Americans prompted the editor of the Chicago Defender to worry about whether African Americans were losing sight of the need to concentrate on struggles at home. In an editorial he cautioned, “Don’t do it, young men and women. There is too much for you to do at home” and wondered if “you suppose your conditions are better than those of the warriors of Ethiopia?” Mrs. Wimley Thompson of New Mexico responded, asking, “Don’t we owe them something?” She thought so: “One must remember that we didn’t come to this country on our own accord, so why should we battle for something we will never receive? Justice. Ethiopia is our country and as long as there is blood in our veins we should love and respect it as such.” She condemned the treatment of black Americans and called on their support for Ethiopia, concluding that “Ethiopia may some day prove to be a place for our future children.” Mrs. Thompson clearly recognized that the violence against Africans in Ethiopia warranted as much resistance as the unfair conditions faced by black Americans.10

These responses to the invasion of Ethiopia, connecting the predicament of blacks globally, can be characterized as a strand of black internationalism. This idea or movement is described by one scholar as “an insurgent political culture emerging in response to slavery, colonialism, and white imperialism,” centered on “visions of freedom and liberation movements among African descended people worldwide. It captures their efforts to forge transnational collaborations and solidarities with other people of color.”11 Black internationalist sensibilities generated activism on the part of women and men of African descent in Africa, Europe, and the Americas into the 1940s and 1950s. In the United States black Americans were particularly sensitive to oppression and discrimination.

African Americans had, after all, entered the twentieth century disenfranchised and subject to increased violence. Though slavery had been abolished, the actual bondage of black Americans continued in the face of discriminatory legislation and practice. Most white Americans believed they were superior to blacks and “the Southern way had become the American way.”12

Between 1930 and 1950 African Americans experienced many changes. In the South Jim Crow laws hampered their progress, and racial terror, lynching, and other forms of intimidation continued to define their daily lives. Although rapid industrialization had broadened opportunities for many, black people were still regarded as second-class citizens in Northern cities. They faced discrimination in public housing, employment, public accommodations, public transportation, and the workplace. Although strides had been made in the courts, white prejudice and the weight of tradition perpetuated segregation.13 American blacks who had been in the United States for several generations identified with values shaped by the dominant culture of white America. Many accepted that they were Americans and gave little thought to identifying with Africa.

W. E. B. Du Bois, fresh from the Pan-African conferences, understood this state of affairs. He wrote that young black Americans did not think of themselves as anything other than American. “It is impossible,” he wrote, “for that boy to think of himself as African, simply because he happens to be black. He is an American.” Yet, Du Bois added, African Americans were a “peculiar sort of American.” Because of discrimination, prejudice, and economic hardship, they would be drawn “nearer to the dark people outside of America” than they would to white Americans. He called for people of African descent in the United States and elsewhere to dispel stereotypes they had of each other. Although large numbers of the black population did not or could not identify with Africa, they could still get involved with African issues and advocate on its behalf. Although they may not have been interested in Africa as a potential homeland, many black American citizens recognized that their ancestry impacted their lives. Indeed, a small number continued the practice of linking themselves with Africa and African issues.14

Writers and artists during the Harlem Renaissance took up Du Bois’s challenge. They embraced Africa, although not always based on accurate knowledge. In this era Americans, black and white, developed a “fascination with the exotic and the primitive.”15 “New Negroes” in the Harlem Renaissance sought to broaden African American conceptions of Africa. As they delved into racial themes, they interrogated what it meant to be black in the United States. In answering this question, they often turned to Africa and its past, one that was frequently romanticized, with emperors, kings, and queens, idyllic landscapes, and welcoming, friendly people. It was in this context that Countee Cullen penned his rumination in “Heritage,” idealizing the link between African Americans and Africa. Other writers also explored ways to incorporate African elements and themes in their art and writing. Some were encouraged to do so by white benefactors and sponsors who wanted a particular image of Africa presented.16

This movement, often called the New Negro movement or the Harlem Renaissance, served to reverse some of the negative ideas associated with Africa. Writers such as Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, among others, tried to understand the African roots of their heritage. Langston Hughes carried on an extensive correspondence with Africans, especially writers, and first traveled to the continent in 1923. Hughes struggled to understand his tie to Africa. Throughout his life he would cultivate and develop relationships with Africans. Zora Neale Hurston used anthropology as a lens to explore Africa and studied African cultural retentions in the American South, where vestiges of African worldviews and cultural forms remained. Historian Leo Hansberry, the philosopher Alain Locke, and other scholars presented diverse perspectives on Africa to students at black colleges and universities, allowing them to embrace a positive identity.17

Locke, a professor at Howard University between the 1920s and 1950s, mentored African students at Howard, including Nnamdi Azikiwe, the future president of Nigeria. A key figure in the Harlem Renaissance, he urged greater study and understanding of Africa and promoted increased contact between Africans and African Americans. In 1924, urging African Americans to take more interest in Africa, he wrote: “With notable exceptions, our interest in Africa has heretofore been sporadic, sentimental and unpractical. . . . The time has come . . . to see Africa, at least with the interest of the rest of the world, if not indeed with a keener, more favored regard.” He believed that “eventually all peoples exhibit the homing instinct and turn back physically or mentally, hopefully and helpfully, to the land of their origin. And we American Negroes in this respect cannot, will not be an exception.”18

Howard history professor Rayford Logan also mentored African students, publishing books on Africa and its relationship to African Americans and the world. Another Howard professor, Alphaeus Hunton, became a strong advocate for the continent. When a young African American asked why he should be concerned with Africa “when we as a minority group catch hell in this country,” Hunton responded:

First, we have to be concerned with the oppression of our Negro brothers in Africa for the very same reason that we here in New York or in any other state in the Union have to be concerned with the plight of our brothers in Tennessee, Mississippi or Alabama. If you say that what goes on in the United States is one thing, quite different from what goes on in the West Indies, Africa or anywhere else affecting black people, the answer is, then you are wrong. Racial oppression and exploitation have a universal pattern, and whether they occur in South Africa, Mississippi or New Jersey, they must be exposed and fought as part of a worldwide system of oppression, the fountain-head of which is today among the reactionary and fascist-minded ruling circles of white America. Jim-Crowism, colonialism and imperialism are not separate enemies, but a single enemy with different faces and different forms. If you are genuinely opposed to Jim-Crowism in America, you must be genuinely opposed to the colonial, imperialist enslavement of our brothers in other lands.19

Hunton would later settle in Africa.

In the interwar years African Americans developed a new regard for Africa in the face of emerging nationalist movements that liberated most of the continent from colonialism. By the end of the Second World War a new group of African nationalists, more impatient and less tolerant of colonial policies, had emerged. Educated in colonial schools established after the Phelps Stokes report, they pushed for greater participation in their own affairs, for more rapid changes, and for eventual decolonization. Many of them had attended black American colleges.

As African Americans fought for their own civil rights, they drew parallels between their struggle and that of Africans fighting for independence. Black Americans formed organizations and groups purporting to speak for Africa and Africans, similar to ones that had existed before. The difference was that by midcentury Africans were challenging the status quo on their own behalf, demanding a place at the table.

Throughout the centuries, as we have seen, some African Americans were afraid of embracing this heritage, seeing it as a threat to their acceptance, inclusion, and integration in American society. Even while some black Americans presented Africa positively, it was equally marked as tribal, exotic, and idyllic. Africa was still an imagined space for many, but one that was becoming real to some black Americans. In the twentieth century some African Americans traveled to the continent, taking it upon themselves to champion African causes in the face of negative representations. Ralph Bunche took a trip to South Africa and East Africa in late 1937 and early 1938. His diaries are rich with observations on African American and Africa connections.

Langston Hughes expressed joy when he arrived in Africa: “And finally, when I saw the dust-green hills in the sunlight, something took hold of me inside. My Africa, Motherland of the Negro peoples! And me a Negro! Africa! The real thing, to be touched and seen, not merely read about in a book.” Yet even then he could not resist the romanticized notion of the continent. As his ship sailed down the West African coast, in words reminiscent of Cullen’s musings, he reflected: “It was more like the Africa I had dreamed about. Wild and lovely, the people dark and beautiful, the palm trees tall, the sun bright, and the rivers deep. The great Africa of my dreams.”20 By glorifying the African past, writers like Hughes hoped to create positive association and identity for black Americans. Yet they recognized, as Cullen did, that they were more American than African. Thus Langston Hughes mused: “I was only an American Negro who had lived the surface of Africa and the rhythms of Africa, but I was not Africa. I was Chicago and Kansas City and Broadway and Harlem.”21

For most black Americans, the continent was an unknown. What they knew of it continued to be filtered through negative depictions in popular culture. Some resented claims of their connections and obligations to Africa. When the virulently racist Senator Bilbo (D-MS) promoted sending African Americans “back to Africa” as a solution to the race problem, African Americans responded with derision. The NAACP published a vocal criticism, citing the words of its Savannah, Georgia, president, Dr. Ralph Mark Gilbert: “Africa is no more the fatherland of the present generation of Negroes than of Anglo-Saxons. Unless your plan is to make a resettlement so as to include peoples of various racial stocks instead of singling the Negro out, I am afraid our people will not get the point. We have no objection to any Negroes who wish to go to Liberia or Egypt or France or Brazil, or any other country to settle, in going ahead and doing it. But, we do not feel that the U.S. Government should single us out to give us help in returning to a land from whence we have never come and concerning which we know nothing by personal contact.”22

In the 1930s and 1940s African Americans challenged discrimination and disfranchisement with a view to shaping the “representation of black people in American society.”23 This required that they revise the dominant portrayals of Africa as backward, savage, and incapable of self-government. In these two decades images of Africa were still largely derived from narratives of missionaries and explorers and, more and more, from representations in film. In this era “jungle” movies presenting Africans as subservient, obsequious, meek, and cowardly were popular. Films like Tarzan the Ape Man (1932), Sanders of the River (1935), and Stanley and Livingstone (1939), among others, contributed to racist modes of thinking.24

Perhaps the most vociferous voice for Africa at that time was that of noted singer, actor, athlete, and activist Paul Robeson. Robeson starred in movies with African settings, often portraying stereotypical versions of Africa and Africans, although he imbued them with dignity. In Sanders of the River he was cast in the unflattering role of an obedient and good African in a colonial space who later rejects the civilizing influence of Europeans. The film portrayed the character, once he had abandoned the European way of life, as a savage despot. Such representations in film served to distance African Americans from the continent the way accounts by missionaries and explorers had in the nineteenth century. Robeson, who became an active member of the Communist Party, later disowned the film, criticizing it for justifying imperialism and for showing Africans in a negative light. Although there were other African Americans speaking on behalf of the continent, Robeson, educated at Rutgers University, where he was an All American football player, was one of the loudest and most famous. W. E. B. Du Bois and Carter G. Woodson also continued to study and write about Africa in this period. In fact, Du Bois, who shared many of Robeson’s political affiliations, was influential in Robeson’s deep interest in Africa, and the men maintained a forty-year friendship.

Paul Robeson became interested in Africa early in his life, but his passionate advocacy began when he lived in England. Years later he would recollect: “I ‘discovered’ Africa in London. That discovery—back in the Twenties—profoundly influenced my life. Like most of Africa’s children in America, I had known little about the land of our fathers.”25 In London Robeson encountered students from the colonies, gleaning a variety of perspectives from the continent. Meeting men like Nnamdi Azikiwe, Jomo Kenyatta, and Kwame Nkrumah, who would go on to lead independent African nations, he became proud of his connection to the continent. Robeson’s passionate fight for civil rights undoubtedly influenced the African struggle for independence. Throughout his life he urged African Americans to learn more about Africa and look to it for inspiration. Although not an advocate of emigration, Robeson believed African Americans had strong ties to the continent and that their future lay in Africa. “For myself,” he proclaimed, “I belong to Africa; if I am not there in body, I am there in spirit.”26 The actor traveled to Africa for the first time in 1937—ironically to Egypt rather than sub-Saharan Africa, in order to film a movie.

In 1937, along with Max Yergan, Du Bois, and Alphaeus Hunton, Robeson founded the Council on African Affairs (CAA), becoming the organization’s chairman. Max Yergan, educated at Shaw University in North Carolina, went to Africa in 1916 under the auspices of the YMCA. He spent two years in Tanganyika and fifteen years in South Africa. While he worked for the YMCA, Yergan also became politically active, working with black South Africans. Upon his return to the United States he became involved with the Council on African Affairs.27 Hunton left his position at Howard University to concentrate full-time on his activism and work with the CAA. Many of the organization’s members had an abiding interest in Africa, believing the continent and its people needed uplift and liberation from European dominance.

Centered in Harlem, New York, the Council on African Affairs’ major purpose was to support anticolonial struggles in Africa, with its stated mission to serve the “interests of the peoples of Africa.” Throughout its existence (it dissolved in 1955), the CAA drew attention to African issues. It especially condemned apartheid and racial segregation in South Africa, no doubt because it saw parallels between that country and the American South. The CAA counted many prominent African Americans among its members and supporters. E. Franklin Frazier, Ralph Bunche, Mary McLeod Bethune, Rayford Logan, and Adam Clayton Powell Jr. were among its prominent members. CAA members supported the organization’s goal of ending colonialism in Africa.

The CAA’s monthly newsletter, New Africa, published in-depth human-interest stories and news from the continent. The group was a conduit between Africans and Americans, raising money to assist African students facing financial difficulties in the United States. Most important, the organization took as its major function “providing Americans with the TRUTH about Africa.” Given the lack of knowledge and prejudices persisting among Americans, this was no small task. Furthermore, many of its members knew little of the continent. Nonetheless, they advocated strongly on its behalf. In a 1945 fund-raising letter, Robeson proclaimed that “the need in Africa is to free its millions from political and economic handicaps, some expressions of which are poverty, illiteracy, insufficient hospitals, and barriers to cultural development. The task is to bring the need strongly enough before the American people and their representatives.”28 The Council on African Affairs, he stressed, had been doing just that.

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s Robeson championed African causes even as he continued to work in the arts. In 1952, accused of being a Communist, he was put under FBI surveillance and had his passport seized. His American critics tried to discredit him among Africans. The Russians used him for propaganda purposes to personify how American blacks suffered from racial persecution, which they presumably implied did not exist in Russia. Regardless of how others sought to use him for their own purposes Robeson was focused on black emancipation. Robeson and his family lived in Europe for many years and upon returning to the United States he continued his activism on behalf of African Americans and Africans.

No less than her husband, Eslanda Robeson was a staunch advocate for Africa. She preceded her more famous husband to Africa, traveling to East and Southern Africa with their young son Pauli in 1936. Ten years later she published African Journey, a chronicle of the months she spent on the continent doing research for her anthropology degree. She acknowledged her African roots, expressing her long-held desire to visit the continent: “I wanted to go to Africa. . . . Africa was the place we Negroes came from originally.” Like the many American immigrants who, when they could, visited their original homelands, “I remember wanting very much to see my ‘old country.’”29 Observing the lack of interest in Africa in the United States, Eslanda, like her husband, acknowledged that living in England had raised her awareness of African issues. She identified with the continent, serving, like her nineteenth-century predecessors, as a vindicator for Africa and its people.

She argued that merely recognizing one’s ancestry was not enough. Long before widespread usage of “African American” as a designation for black Americans, Eslanda Robeson mused on its use. “The term African American,” she wrote, “can provide then only an artificial sense of homeland or nationality, for Africa is not a nation but a huge heterogeneous continent.” She recognized that the “Africa” of her childhood was an “imagined community.” In African Journey she meditated on many aspects of the communities she visited, illuminating their diversity and difference, even commenting on the strangeness of some of the customs. This was a firsthand view of Africans in their own milieu. She voiced her opinion on the need for education in Africa, arguing for the benefits and advancement this would bring. Most of all she articulated the idea that Africa was coming into its own. In the postwar period, “the people of the world will have to consider the people of Africa.” “Africans,” she concluded her book, “are people.”30 This was an idea that bore repeating in the United States, despite growing knowledge about the continent. Eslanda would return to Africa in 1946 and again in 1958 for the All Africa People’s Conference in the wake of Ghana’s independence. In 1953 the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) questioned Robeson about her books. She defended her patriotism and expressed her pride in being Paul Robeson’s wife. Her commitment to Africa did not prevent her from embracing America.

Forced to engage with Africa in multidimensional ways, African Americans sought different paths. The assortment of views historically characterizing African American attitudes to Africa persisted. Some, like the Robesons, chose to identify with the continent and its people. Others rejected any notion of an affinity to it. Though not identifying strongly with Africa or expressing any desire to connect in any way with the continent, they still believed in the right of Africans to self-determination. The noted sociologist E. Franklin Frazier, for example, had long argued that the experience of slavery had eradicated the African cultural heritage in African American life and culture. He maintained that there were few African antecedents in the structure of the black family in America, believing that “memories of the homeland were effaced, and what they retained of African ways and conceptions of life ceased to have meaning in the new environment.”31 Yet even he recognized the integral connections between the fate of Africa and African Americans. Along with Rayford Logan he pushed for African studies programs at Howard University.

Eslanda Goode Robeson speaking at an Africa Women’s Day gathering, n.d.

(Photographs and Prints Division. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. New York Public Library Digital Collections.)

As the Cold War intensified, black Americans went to great pains to show loyalty to the United States, wary of embracing anything that might call their patriotism into question. Unfortunately, cries against colonialism were often construed as disloyalty or split loyalty. More and more African Americans eschewed anticolonialism. Yet even those who believed their attention and energies should be focused on the plight of African Americans allied themselves with the anticolonial movement. Men and women in the labor movement, for instance, saw commonalities between their issues and those of Africans. A. Philip Randolph and Maida Springer best exemplify this.

Yevette Richards has shown how Springer’s work with the international labor movement brought her into contact with African labor leaders in the 1950s. Working closely with Randolph, they promoted Pan-African labor struggles and were defenders of nationalist and labor movements on the continent. Springer, she notes, “expressed longing to visit Africa.”32 She was able to do so in 1953. In 1959 she also worked in Tanzania and Kenya. A. Philip Randolph, though largely focused on labor issues in the United States, also spoke out against colonialism in Africa. He corresponded with African labor leaders and helped develop labor movements on the continent. Randolph piloted an American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations’ (AFL-CIO) program to train African labor leaders.33

By the 1950s activism on behalf of Africa had given way to a more conservative and cautious approach toward the anticolonial struggle and identification with Africa. Where in the past disparate groups had agreed on the issue of colonialism, engaging in anticolonial activity, a split now occurred. A strong anti-Communist strand also emerged in the rhetoric of some black leaders as they distanced themselves from African issues. Many turned to support American foreign policy, which often meant backing European colonial powers. Fearing accusations of disloyalty to their country, some backed away from active engagement with issues putting them in conflict with the U.S. government. Hesitant to criticize their government and its policies, black Americans embraced their American identity. The CAA soon dissolved over conflicts between members like Robeson and Du Bois, who continued to link African and African American problems, and others, including Max Yergan, who became more conservative. Yergan turned against the group around 1948.34

The NAACP, which under Du Bois’s leadership had linked the plight of blacks globally, now increasingly focused on American concerns. “Negroes are American,” Walter White of the NAACP asserted. In 1956 Kwame Nkrumah criticized the NAACP for being “exclusively concerned” with race policies domestically, at the expense of a broader vision for black liberation. Recently the historian Carol Anderson has made a case that the NAACP, contrary to Nkrumah’s criticism, was in fact very much engaged with African issues. Although this was indeed the case, this commitment was, arguably, part of a larger agenda of anticolonialism worldwide. Nonetheless, nascent African nations recognized their debt to the organization. In 1959, on the occasion of the NAACP’s fiftieth anniversary, Nnamdi Azikiwe, once a student at Lincoln and Howard, expressed his gratitude for its influence:

The NAACP has been an inspiration to me and to my colleagues who have struggled in these past years in order to strengthen the cause of democracy and revive the stature of man in my country. As a student in this country from 1925–1934, I had the opportunity of being fed with my American cousins what Claude McKay called the “bread of bitterness.” But I have also had the unique honour of sharing with these underprivileged God’s own children the challenge to conquer man-made barriers and to forge ahead to the stars, “in spite of handicaps.” This spirit of the American Negro, as exemplified in the constitutional struggles of the NAACP, has borne fruits of victory in the course of the years. It has given the United States a fair chance of reconciling the theory of democracy with its practice in America. It has also fired the imagination of the sleeping African giant, who is now waking up and taking his rightful place in the comity of Nations. What a glorious victory for the American Negro!35

For leaders of the NAACP who sought to be included in U.S. foreign policy decisions, Africa seemed a logical pathway. Many African Americans embraced anti-Communism in a bid to show their patriotism, highlighting the differences between African Americans and Africans. They often became the accepted and acceptable spokespeople for black Americans as they shaped the discussion of Africa and anticolonialism. African Americans had become more demanding of the rights due to them and wanted to have a greater voice in discussions of America’s relationship with Africa. While some black Americans distanced themselves from Africa, others took advantage of a new strand of interest in Africa emerging in the 1940s and 1950s. Even as African American identification with Africa diminished, the U.S. government and other mainstream organizations turned their gaze toward the continent. It became a foreign policy focus as the American government, within the context of the Cold War, found it had strategic interests in some parts of the continent.

Greater interest in African resources prompted funding of organizations that could produce knowledge of the continent. Organizations such as the American Committee on Africa (ACOA), founded by the white American George Houser in 1953, attracted black members. ACOA was a national organization founded to support the liberation struggle against colonialism and apartheid. It emerged out of a smaller organization, Americans for South African Resistance (AFSAR), which had formed to support the Campaign of Defiance against Unjust Laws spearheaded by the African National Congress (ANC). Other black-led organizations also emerged in this era. African American luminaries like Springer and Randolph were members.36

As always, black Americans tried to speak for Africa. In April 1954 the Council on African Affairs held a “Working Conference in support of African Liberation” at the Friendship Baptist Church in New York City. W. E. B. Du Bois and Alphaeus Hunton were included in the roster of speakers. Long before the anti-apartheid movement of the 1970s and 1980s, participants at the conference called for protest against racial injustice in South Africa. They drew parallels between lynching in the United States and the exploitation of black South Africans, condemned the brutality of the South African government in its response to striking miners, and criticized the pass laws system that restricted the movement of blacks. The treatment of Africans in “native reserves” was highlighted as horrendous, and the CAA pledged to send money to help “starving Africans.” Among the resolutions at the conference was a call for protests at the South African embassy in Washington, DC, and a decision to urge President Harry Truman and other officials to protest discrimination.37

Some African Americans at this time posited themselves as experts on African issues, history, and “problems,” and policy makers with growing interests in Africa often called upon them. Perhaps for the first time we see the rise of a class of black American “consultants” on Africa, men and women turned to for their knowledge of the continent. Although in smaller circles a less visible and vocal group of African Americans continued to promote the idea of Africa as diverse, there was a general disinterest in Africa and its people. There was less coverage of Africa in the black press. Reporting was scanty and presented the continent as exotic.

Yet more than ever African Americans were traveling to Africa. Claude Barnett, founder of the Associated Negro Press (ANP) in 1919, engaged extensively with Africa. Barnett and his wife, the actress and singer Etta Moten, traveled to West Africa in 1947, visiting Liberia, Sierra Leone, Nigeria, and the Gold Coast under the auspices of the Phelps Stokes Fund. In explaining the reason for the Barnetts’ trip, Channing Tobias of Phelps Stokes observed that “with Mr. Barnett’s access to a large number of publications in the United States, it is believed that the knowledge which he may gain of the people of West Africa, their conditions and aspirations, etc., will enable him to present a statement to the American public which will improve their understanding of West Africa. Also he should be able to give a picture of the American people and institutions which may be helpful to the people of Africa.”38

On their return the Barnetts wrote “A West African Journey,” in which they chronicled their experiences in West Africa. In Liberia they visited the Booker Washington Institute. Among those they met in Sierra Leone were individuals with American connections: Adelaide Casely Hayford, the “distinguished and cultural elder citizen” who had visited the United States in the 1920s, along with some of her Easmon relatives, S. M. Broderick and Solomon Caulker, who had studied in the United States and were both now at Fourah Bay College. The Barnetts were met at the airport by Caulker, who had received his degree in education from the University of Chicago in 1945, and his wife, Olive, “an American girl, daughter of Dr. E. A Selby of Nashville.” Olive had met her husband at the University of Chicago, where she received her master’s degree in education. In this union between an African and an African American, the couple saw great potential: “The romance which developed on the campus blossomed into marriage and these two fine young people are now both members of the faculty of Fourah Bay College in Freetown.”39

Claude Barnett was impressed by the West African press, which he described as “almost totally organs of protest.” Azikiwe’s newspaper in particular was labeled an agitator. In Nigeria Barnett met Mbonu Ojike, who had received his degree from Chicago in 1945 and was now a devotee of Nnamdi Azikiwe, serving as the general manager of the Zik Papers, a reference to the newspaper started by Azikiwe. Barnett also met Prince Nwafor Orizu, “another American trained Ibo,” a founding member of the African Students Association now back in his homeland.40 Upon his return Orizu started a scholarship program to send Nigerian students to the United States. Like Ojike, he admired his fellow American-trained leader Azikiwe.

Although they were invited to events where whites mingled with Africans in the colonies, the Barnetts also saw examples of segregation (the hospitals in Accra and the whites-only YMCA). They observed that the mixed-company events were those where “people wanted to let their hair down and the topic of conversation was ‘the race problem.’” Africans were interested in African American life and experiences and questioned Mr. and Mrs. Barnett about lynching. They expressed hope that black Americans would make a contribution to the “upward progress of Africans.”41

On the return trip Barnett met with Creech Jones, British secretary of state for the colonies, who “reacted favorably toward the idea of using American Negro teachers in West Africa.” He followed up with a letter to W.E.F. Ward, the deputy adviser in education at the Colonial Office, expressing the idea of promoting African American teachers and missionaries in Africa who, he argued, would be helpful in explaining Africa to Americans. He asked for more information on Africa and stressed the need for training more Africans at institutions like Tuskegee and Hampton. Barnett believed that Africans would be receptive to African Americans in this role, declaring: “Finally, the growth of interest on the part of American Negroes in Africans and of Africans in their kin across the sea through such a program, could prove a most helpful and useful relationship during the years to come. Such an achievement would pay big dividends in the development of understanding, progress and good will.”42 Claude Barnett maintained ties to the continent, visiting several times over the next decade or two. Those who had direct experience with the continent strove to present it as diverse, modern, and progressive. The growing number of Africans living in the United States supported this image.

There was a small but vocal group of Africans in the United States who considered themselves equipped to be spokespeople for Africa. Increasingly, Africans began to speak on African issues, form groups, push for greater attention to Africa, and call for changes in their homeland. In the 1940s and 1950s more Africans were studying in the United States, engaging with African Americans and sharing their history and culture. Housing discrimination meant they could not find living spaces in nonblack neighborhoods. African students often lived with black American families in black neighborhoods. Harlem, for instance, served as a safe haven for black immigrants in the era of segregation. Africans created ties with African Americans in this milieu as they observed what life was like for people of African descent. Having rubbed shoulders with their African American classmates, landladies, and hosts, they learned firsthand of discrimination and segregation, and witnessed challenges to the status quo.

Some of the first leaders of independent African nations studied in the United States, often in black colleges and universities. Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana studied at Lincoln University; Nnamdi Azikiwe from Nigeria studied at Howard and Lincoln. In their autobiographies both men noted the great influence Lincoln and its black American students and faculty exerted on them. Hastings Banda from Malawi studied at Central State University, a historically black college in Ohio. All three went on to lead their countries at independence. Many others took leadership roles in nationalist movements and later in newly independent governments.

African students sometimes gave accounts of their African and American experiences and their observations on American life. Mbonu Ojike wrote My Africa and I Have Two Countries. The first was billed as a book in which “a Native Son tells the true story of Africa.” The promotional pamphlet dramatically declared, “Africa speaks”: “The truth about the ‘Dark’ Continent; the explosion of outmoded ideas of Africa as a sort of museum piece or zoo; a true picture of the continent—a mixture of the primitive and modern—but entirely contemporary with the rest of the world in hope, effort and aspiration toward peace and a co-operative security.”43 Some students and visitors depicted the United States as hospitable to Africans, but their observations of American life were not always flattering.

A few women helped shape American views of the continent. Female students showed African Americans a different side of Africa. In February 1945 the Baltimore Afro-American reported the conclusion to the case of the “daughter of an African King.” Princess Fatima Massaquoi won a lawsuit over who had the right to publish her autobiography, begun as a class paper at Fisk University and completed in 1946 at Boston University. Fatima filed the suit against parties at Fisk who, she argued, had appropriated her work. The biography gave glimpses into Vai culture and customs, as she understood them, describing childbirth beliefs, marriage practices, and funeral and food customs. It was clearly directed at an audience with stock images of Africa, and Fatima took pains to present an Africa with cultures, civilizations, and values equal to those of the West. Fatima’s father, Momolu Massaquoi, had studied at Central Tennessee University in 1892, becoming one of the first Africans to study at American institutions. While in the United States he was a frequent lecturer on Africa. Welcomed by African Americans, many of whom were friends of her father, Fatima remarked upon the kindness she received from black Americans.

Yet stereotypes about Africa prevailed. Fatima poignantly writes of her experiences of being portrayed as exotic. Those she encountered sought to place her within a context of an Africa they had imagined. One of the more disquieting episodes she describes illustrates the beliefs African Americans had imbibed. When Fatima arrived at Lane College, a historically black institution, some of the female students, seeking to make the new girl from Africa feel welcome, painted their faces and decorated their hair with feathers. Given the prevailing images of Africans abounding at the time, they expected to see a young woman just snatched out of the wilderness. The “savage” turned out to be the poised, cosmopolitan, well-educated daughter of a diplomat, a young woman who had been schooled in Germany, traveled widely in Europe, rubbed shoulders with dignitaries, and spoke several languages. In her autobiography she hoped to give Americans a more realistic view of her homeland. Explaining why she fought so hard for the rights to her own story, Fatima told the Afro American, “My autobiography is my soul and my heritage, and I couldn’t go home to Liberia and look my family in the face after selling my culture and heritage for a mess of pottage.”44

African students, though small in number, were forceful in drawing attention to African issues. In fact, African students in the United States had formed organizations as early as 1919 when Simbini Nkomo organized a conference in Chicago.45 Students concerned with the welfare of their compatriots from all over the continent founded the African Students Association in 1941. Its student creators, John Karefa Smart from Sierra Leone and Prince Nwafor Orizu from Nigeria, recognized that the war had made it difficult for many to get financial aid from families back home. The group came together as a source of support for students in the United States and as a resource on Africa and African concerns.

The African Academy of Arts and Research, designed to teach Americans about Africa, was an offshoot of the student association. The academy published a monthly newsletter with articles directed at Africans on the continent and news about international events affecting them. The organization frequently put out pieces meant to inform its members of their duty to the continent. These young men and women helped shape American views of Africa, although they more often than not reinforced stereotypes of the continent by making sweeping generalizations. Wherever possible they strove to illustrate Africa’s diversity, but recognized that Americans were largely ignorant of the continent and its diverse populations. For example, the author of the academy’s February 1942 newsletter made a point of clarifying his use of the term Africa as an “ideological whole, as the symbol, the concentration, the whole dimensional range of all his best wishes, dreams, and hopes. He means the continent—home, the fatherland. Mother Africa.”46 This explanation would hardly have clarified how heterogeneous Africa was.

Arguably, African students in the 1940s used the term African much as African Americans had for centuries, symbolically to embrace the continent of their ancestors. The students were clear that each of them used it denote his or her specific place of origin on the continent: “And what is so incomprehensible about the thought of an African visualizing the whole of Africa, while really talking about Nigerian schools or about chieftaincy in Basutoland? Does Maine speak for Mississippi, even though both believe in an American ideal termed democracy?”47 The organization embraced a Pan-African ideal of African unity while indicating to American readers the continent’s diversity. American interest in Africa surged after the Second World War, and the various organizations with an Africa focus looked to African students for expertise on their countries. The African Studies Association and the African Academy of Arts and Research provided that knowledge base, and continental Africans increasingly became the voice of Africa. Called upon to give their views on the continent’s readiness for independence, many spoke out against colonialism and lobbied for U.S. involvement.

Africans who had studied in American universities returned with nationalist fervor, politicized and pushing for change. As independence movements took off in African colonies, leaders of nationalist parties often reached out to African Americans for support. Interaction between the two groups intensified as they sought a closer relationship. In 1958, for example, the New York chapter of the National Negro Business League, an organization founded by Booker T. Washington in 1900, invited Madam Ella Koblo Gulama, a member of Parliament and paramount chief from Sierra Leone, to provide “the first opportunity for business people in our community to hear about economic development in Sierra Leone, one of the several countries of Africa now readying itself for self-government.”48 Indeed, the small but active Sierra Leonean population in New York celebrated when the country finally gained independence in 1961. The Sierra Leone Society of Greater New York and Vicinity put together an independence celebration, highlighting the country and its potential. The souvenir journal, complete with pictures, maps, and advertisements, also showcased the musician Babatunde Olatunji and his “drums of passion,” calling for readers to “come on a safe safari to musical Africa.” Mrs. Gulama, upon arrival, noted her interest in seeing “how Negroes live in the United States,” and in observing the “development of the relationship between the races.”49

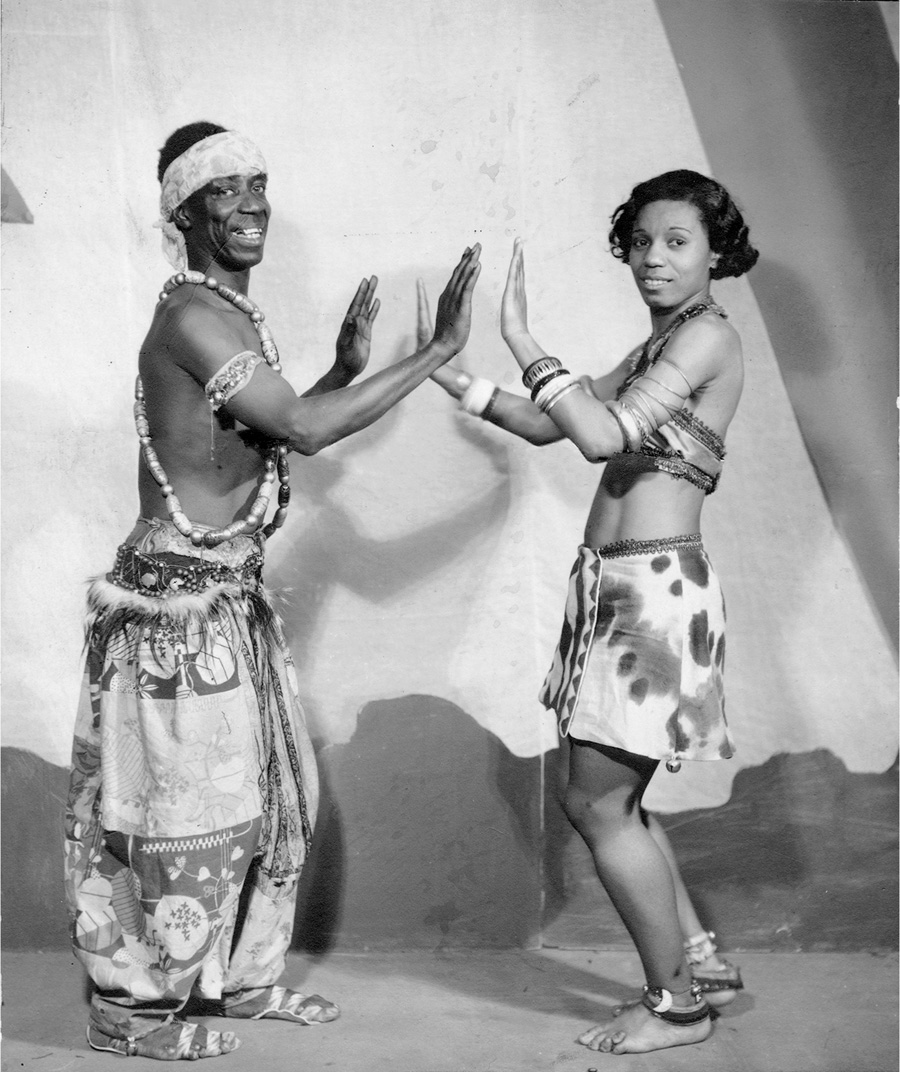

An early member of the African Academy of Arts and Research, Dafora was featured on the cover of its informational brochure when the academy hosted its first big event, an African Dance Festival, at Carnegie Hall in December 1943. He collaborated extensively with African American artists, including them in his productions. Among the artists he worked with were Esther Rolle, later known for her role as Florida Evans on the television series Good Times, and Pearl Primus, the African American choreographer. When Nkrumah visited the United States in 1958, Dafora put on a performance of his famous play Zunguru, described as a “native African Dance Drama” at the United Mutual Auditorium on Lenox Avenue in New York City. Among those featured were Babatunde Olatunji and Rolle.50

Recognizing that popular culture was an important avenue through which Americans could understand the continent, the academy focused on dance and music. It garnered support from and established relationships with key African American figures such as Mary McLeod Bethune, one of the festival’s major patrons, along with Eleanor Roosevelt and several prominent black American sponsors, including Walter White of the NAACP. Alain Locke also served as an officer of the academy. Kingsley Ozuomba Mbadiwe, the founder and president of the academy, wrote frequently to Bethune, apprising her of events and initiatives. In a letter thanking her for her support of the festival, Mbadiwe reminded Mrs. Bethune of the deep connections between African Americans and Africa, stressing Africa’s need for African American support: “We cannot do these things alone, we must draw spiritual energy from our sons and daughters who though many generations removed, but still wear that badge.” Mbadiwe reminded Bethune of the speech she had made at Carnegie Hall asserting her relationship with Africa: “You can well remember your speech at Carnegie Hall when you said ‘I did not know that this day will come, but here I stand saying without apology that the queenly blood of Africa runs through my veins.’”51

(Photographs and Prints Division. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. New York Public Library Digital Collections.)

Mary McLeod Bethune had always expressed pride in her African ancestry and shown interest in the continent. Her desire to help Africa and Africans, Paula Giddings has explained, “was inspired both by religion and by a special feeling regarding her heritage.” She tried unsuccessfully to go to Africa, soon recognizing that her “primary mission was in America.”52 Bethune remained engaged with African issues, donating money and time to the cause of the academy and other initiatives. She received many letters from African students requesting her help and sending her information on what was going on in their countries.

In 1950 Bethune was asked to be on the advisory board of a proposed college in the Gold Coast. The “Afro-College” was to be supported by “Americans of African Descent.” Resonant of Booker T. Washington’s philosophy, it would provide a curriculum adapted to the needs of Africans, with less stress on classical education and more on vocational and technical skills. It called for an improvement in the education of girls. The proponents of the Afro-College, complaining that Africans educated in the United States were marginalized upon their return, hoped the college would use them to greater effect to “correct those mistakes which the present West African educators have made.” Such an institution would have African and African American faculty, be led by an African president, and would “bridge the gap between the American Negro and the African.”53

In 1954 Bethune was asked to be a board member of the African Cultural Society, whose focus was on education and culture with the aim of promoting goodwill and friendship between Africans and Americans. The society’s motto, “To know each other—to learn from each other—to understand each other,” must have resonated with her. Bethune expressed her continuing regard for the continent and its people by noting in the margins of the letter, and in her response to the invitation: “I am much interested in Africa.”54

Africans on the continent communicated frequently with African Americans, asking for help, urging cooperation and unity. Henrietta Peters, headmistress of the West African Industrial Academy in the Gold Coast, wrote to Sallie Wyatt Stewart, who succeeded Mary McLeod Bethune as president of the National Association of Colored Women, asking for collaboration. She informed Stewart that the West African Women’s Union had been formed and asked for a “proper person to instruct us.” All the union’s members were Africans, but “our membership will include any women of African descent resident in West Africa, if more foreign-born women of colour come to our coast.” Peters asked for literature and material to be sent to her organization “for our women to study the activities of the women in America that it may inspire these here.” She also asked for information on more African American organizations with which to correspond. Africans on the continent, who for centuries had kept abreast of the activities of African Americans, were now able to directly communicate with them more frequently.55

African American academics and intellectuals also wrote extensively about Africa in this era. Scholarly writing about the continent proliferated in the American academy. Although many of those writing about the continent were white Americans, black American academics also took the mantle of writing about Africa. Elliott Skinner, St. Clair Drake, and John Henrik Clarke, among others, sought to shape a positive narrative of the continent. As we have seen, there was a long tradition of African American intellectuals like Du Bois and Woodson producing scholarship on Africa, challenging the idea of Africa as a “Dark Continent.”56

The 1950s and 1960s saw greater African American engagement with Africa as the civil rights movement in the United States paralleled liberation struggles in Africa. James Meriwether has illustrated quite persuasively how African nationalist movements influenced black Americans, shaping the discourse on civil rights. African Americans often drew their government’s attention to the fact that while black American citizens continued to live under discrimination and segregation, their counterparts in Africa were achieving gains under colonialism. Sometimes to get this point across they resorted to negative representations of the continent. There was a return, in some quarters, to depicting Africa as primitive, with some arguing that Africans were not ready for independence. This was the view of George McCray of Chicago, who argued that although Africans sought Westernization and inclusion in their own affairs, they were not ready for self-government. He believed Europeans should stay on the continent for a while longer and that Africans should be told about black American achievements. “I think American Negroes,” he ruminated, “can do a great deal on behalf of a sound African point of view.”57

Africans, however, did not wait on African Americans to seize their freedom. Many of the young men and women who had studied in the United States and returned to Africa were frequently at the forefront of movements demanding changes, however gradual. Joined by compatriots on the continent who had been challenging colonialism on the ground, the nationalist movement gained ground. By the mid-1950s it was clear that colonialism was on the wane in Africa. As Africa gained its independence, black Americans had to figure out the nature of the relationship they would have with the continent’s new nation-states.58