Six

War of Words

1.

By the second third of the century, the struggle by and for fugitive slaves had opened a new front in which the weapons were words. With no solution to the problem of comity even remotely in sight, America’s internal slave traffic—many thousands moving south within the slave states against their will, many fewer moving north out of the slave states by strength of will—was becoming ever more visible.

Between 1800 and 1830, the number of newspapers in the United States rose from around two hundred to nearly a thousand. By 1840, in New York City alone, some thirty thousand copies of antislavery publications were being printed every month. Ten years later, visiting the offices of Horace Greeley’s New-York Tribune, Richard Henry Dana Jr., author of the bestselling memoir Two Years Before the Mast (1840), realized he was witnessing “the great enginery of the 19th century, steam engines in every part of the huge building, & four editors at humble tables, with pen & scissors in hand, preparing for 100,000 readers & more, with telegraphic despatches every hour, from all parts of the Union.” As this new world came into being, slave hunters and their allies might still hope for public indifference, but they could no longer count on public ignorance.

In 1836, a black steamboat worker in St. Louis was under pursuit by police—perhaps because he had been involved in a fight with another sailor—when a free man of mixed race named Francis McIntosh who worked as a cook on another steamboat was arrested for failing to heed the officers’ call to aid them. Told that his offense would land him in prison for five years, he drew a knife, wounding one of the officers and killing the other. After being hauled off to jail, McIntosh was “taken from prison by a mob,” then “chained to a tree at the corner of Seventh and Chestnut. Chests, barrels and lumber were piled about him. This was then lit, and the unfortunate man was slowly roasted to death” while he begged for someone in the crowd to shoot him.

Such stories were now much more likely to spread beyond the sight and smell of the fire. The St. Louis incident became so widely known that more than a year later Abraham Lincoln, just stepping out into the public sphere, told an audience in Springfield, Illinois, that a “mulatto man” had been “seized in the street” in the major city of a neighboring state, “dragged to the suburbs of the city, chained to a tree, and actually burned to death; and all within a single hour from the time he had been a freeman, attending to his own business, and at peace with the world.”

Two months before Lincoln spoke, a pro-slavery mob assembled across the river from St. Louis in the Illinois town of Alton, set fire to the house of the abolitionist newspaper editor Elijah Lovejoy, shot him to death, and threw his printing press into the river. John Quincy Adams called it “the most atrocious case of mob rioting which ever disgraced this Country.” Lincoln feared that the United States was sliding toward anarchy.

Part of what was happening was that abolitionism, once a fringe movement, was gaining strength, and so was the reaction against it. In Washington, under “the dark and threatening cloud of abolition,” senators and representatives fell into mutual recrimination. This was as true in some state legislatures as it was in Congress. In Virginia, where small farmers in the Piedmont and mountainous west resented the slave-owning elite concentrated in the tidewater east, the last substantive debate over emancipation took place during the legislative session of 1831–1832, ending with the nondecision that we must “await a more definite development of public opinion.” If nineteenth-century Virginians had known Samuel Beckett’s twentieth-century play, they might as well have said they were waiting for Godot.

One effect of the political paralysis was to force antislavery into new channels. Among them was a new kind of writing: personal accounts by and about slaves who ran from slavery. At first white writers presumed to tell their stories for them on the assumption that the poor creatures were incapable of speaking for themselves. Self-appointed spokesmen included estimable authors with stately three-part names—John Greenleaf Whittier, James Russell Lowell, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow—known for specializing in safe subjects like the serenities of nature or the pleasures of holiday hayrides. Their rolling rhythms and memory-assisting rhymes made for poetry that parents could recite around the hearth to their children.

But now the “Fireside Poets” took up darker themes, as in Whittier’s “Hunters of Men,” published in 1835:

HAVE ye heard of our hunting, o’er mountain and glen,

Through cane-brake and forest,—the hunting of men?

The lords of our land to this hunting have gone,

As the fox-hunter follows the sound of the horn;

Hark! the cheer and the hallo! the crack of the whip,

And the yell of the hound as he fastens his grip!

All blithe are our hunters, and noble their match,

Though hundreds are caught, there are millions to catch.

Like Bible verse in a good Protestant home, this kind of writing was meant to be read aloud as an aid to moral reflection. Children had many questions. Who were these mounted men? What prey were they chasing? How could their grisly work be a “noble” adventure?

Garrison himself, who had published Whittier’s first poem in 1826 (about an Irish emigrant longing for his native land), tried his hand at child’s verse on the premise that the struggle against slavery must begin with young minds “untainted” by the poison of race prejudice. In his Juvenile Poems, for the Use of Free American Children, of Every Complexion, also published in 1835, he addressed one of his short poems to a plate of sugarplums:

For the poor slaves have labored, far down in the south,

To make you so sweet, and so nice for my mouth;

But I want no slaves toiling for me in the sun,

Driven on with the whip, till the long day is done.

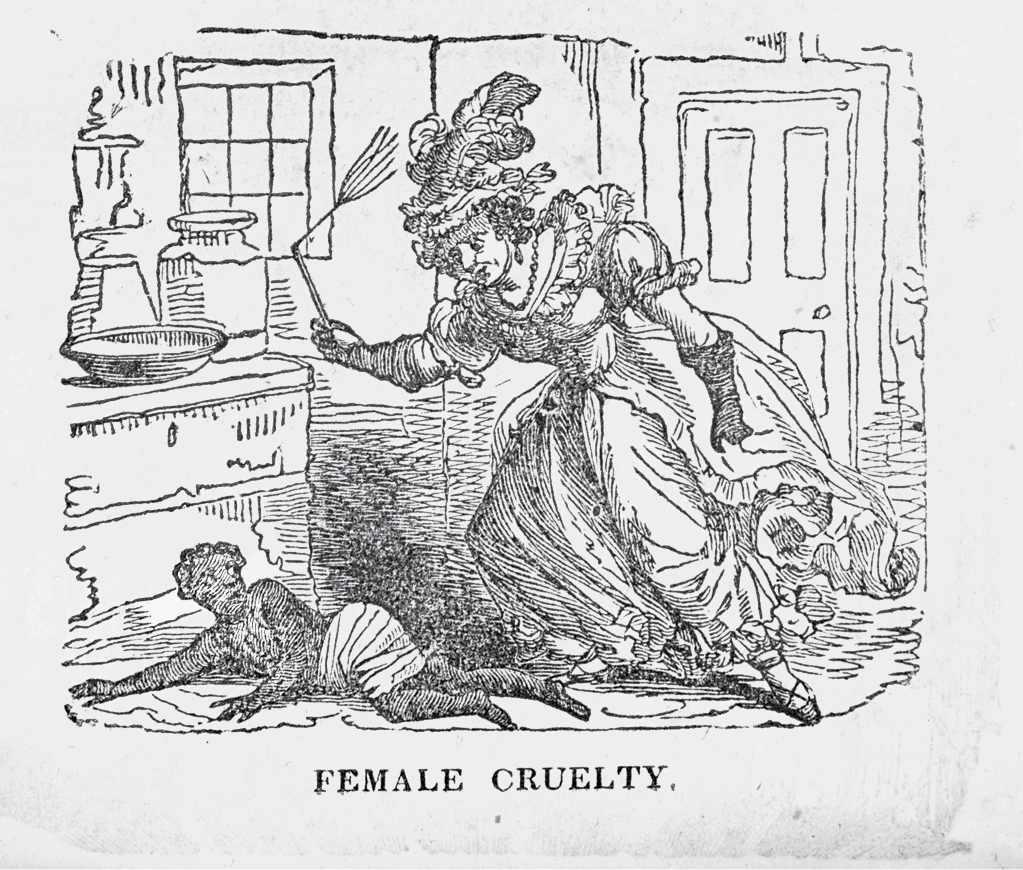

The point of such writing was to make slavery vivid to the mind’s eye—to help readers, especially the young, see the desperate “whip-scarred” runaways until no one could “look upon [slavery] as mere abstraction.” Like Whittier, Garrison hoped to evoke images in the minds of his readers, and in his case he supplemented his words with actual pictures:

“Female Cruelty” from Garrison’s Juvenile Poems

Visual representations of slaves and those who hunted them did not stop with book illustrations. They were imprinted on porcelain plates, carved in the handles of silverware, sewn into quilts, embossed on window blinds, so that the mundane activities of daily life—setting the table, making the bed, screening out sunlight by day and darkness by night—would not hide what went on beyond the glass: “runaways hunted with blood-hounds into swamps and hills.” The phrase came from Emerson, who caustically remarked, in 1844, that when New Englanders sat down to tea and crumpets, they found that “the sugar is excellent” and “nobody tasted blood” in the treats.

2.

The work of rescuing fugitive slaves from invisibility was becoming a transatlantic literary project. In England, Elizabeth Barrett Browning joined the cause with “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point,” about an enslaved woman who strangles her “too white” child conceived in rape by her master—a poem so dark that the editors of The Liberty Bell took two years to ponder it between its submission in 1846 and its publication in 1848.

Meanwhile, in America, the escaped slave was already a stock literary character. In The Fugitives (1841), an amateur theatrical performed in the hope that dramatizing the lives of runaways would do more for the cause than lectures or sermons could do, a fugitive mother watches her daughter while she sleeps:

How I love to look upon her as she

Breathes so gently:—now she sighs, poor thing!

No doubt her womanish heart is shaken

By sad dreams, the fear that we may never

Reach that stream, which crossed, will give us Freedom.

In “The Fugitive Slave’s Apostrophe to the North Star,” written in 1839, the Connecticut poet John Pierpont imagined a plantation slave plotting his escape while hiding from his overseer in a treetop:

In the dark top of southern pines

I nestled, when the driver’s horn

Called to the field, in lengthening lines,

My fellows at the break of morn.

And there I lay, till thy sweet face

Looked in upon “my hiding-place.”

Then, we are left to imagine, he moved on, looking up to the North Star to guide him by night.

All these writers were making a good-faith effort to redress the problem, in the words of Wendell Phillips, of having “been left long enough to gather the character of slaves from the involuntary evidence of the masters.” But on the literary evidence, it was not always much preferable to turn the task over to white writers striving to imagine what they were writing about. In 1842, John Collins, secretary of the Massachusetts Anti-slavery Society, made the salient point. “The public,” he wrote to Garrison, “have itching ears to hear a colored man speak, and particularly a slave.” In Frederick Douglass they found their man.

Born in 1818 in Talbot County, Maryland, Douglass was owned from age eight to eighteen by a merchant named Thomas Auld, who had inherited the boy from his father-in-law, Aaron Anthony, who might also have been Frederick’s father by one of his slaves, Harriet Bailey. Young Frederick Bailey (he took the name Douglass years later, from a swashbuckling character in a poem by Sir Walter Scott) was traded back and forth between the rural household of Thomas and Lucretia Anthony Auld and that of Thomas’s brother Hugh, in Baltimore, where Hugh’s wife, Sophia, instructed the precocious child in the rudiments of reading. Although Maryland was among the few slave states where teaching literacy to slaves was not illegal, Hugh put a stop to it on the grounds (in Douglass’s recollection) that “if you give a nigger an inch, he will take an ell.” By observing white children at their lessons, the boy continued his education surreptitiously.

With a reputation for truculence as well as great intelligence, Douglass was treated sometimes as a family servant, sometimes as an adoptive son, and sometimes as a piece of equipment to be rented out for cash. In an incident about which he spoke and wrote often in later life, he fought off a brutal slave breaker to whom Thomas Auld had sent him and who tried to beat him for his insolence before retreating in terror from the young man’s fury. In 1836, barely eighteen, Douglass joined a plot to flee to the North, but when his co-conspirators lost their nerve, the plan fell apart.

In September 1838, he tried again, and this time he succeeded. Having acquired identification papers from a free black seaman (whether by purchase or as a gift is unclear), he traveled, in sailor’s garb, via train, steamboat, and ferry through Delaware and Pennsylvania to New York City, where he was sheltered by members of the Underground Railroad. But New York proved to be only a temporary haven. Even “black people in New York were not to be trusted,” he later recalled, and some, “for a few dollars, would betray me into the hands of the slave-catchers.”

He stayed just long enough to be married—by James Pennington, also a Maryland runaway, now a Presbyterian minister in Brooklyn—to Anna Murray, a free black woman whom he had known in Baltimore and who had journeyed north to join him. Finding it too dangerous to go “on the wharves to work, or to a boarding-house to board,” lest word get out that his capture might yield a handsome reward, he moved with his wife to Massachusetts, where, in the seaport towns of New Bedford and Lynn, he “sawed wood, shoveled coal, dug cellars, moved rubbish . . . , loaded and unloaded vessels, and scoured their cabins.”

It was his first taste of self-reliance. But what Douglass found in “the grand old commonwealth of Massachusetts” was more than compensated work. He found his calling. Having begun to “whisper in private, among the white laborers on the wharves . . . the truths which burned in my heart,” he ventured, in the spring of 1839, to an antislavery meeting where Garrison spoke, and felt his “heart bounding at every true utterance against the slave system.”

Two years later, at the invitation of another member of the abolitionist aristocracy, William C. Coffin, he joined an antislavery gathering on Nantucket, with Garrison again presiding. In the Quaker spirit of that meeting, he rose spontaneously to speak—an event he later described, using the language of religious conversion, as the moment when there “opened upon me a new life—a life for which I had had no preparation.” His hearers were stunned by his eloquence. “Urgently solicited to become an agent” of the Massachusetts Anti-slavery Society, he was sent on a speaking tour through New England, New York, and as far west as Ohio and Indiana.

Frederick Douglass in 1843

One can only imagine what it was like to hear him. As a child in Maryland, he might have picked up a New England intonation from white playmates who were being trained in elocution by a tutor from Massachusetts. Now, on the stump in the North, he found that “people doubted if I had ever been a slave . . . [because] I did not talk like a slave, look like a slave, nor act like a slave,” so his managers advised him to adopt “a little of the plantation manner of speech.” An imposing man with leonine hair, he had a booming voice and seemed always on the verge of exploding. “Fred Douglass,” according to one acquaintance, “was a tornado in a forest.”

Other speakers in demand included Josiah Henson (escaped from Maryland, in 1830), William Wells Brown* (from Kentucky, in 1834), Henry Bibb (also from Kentucky, in 1842), Ellen and William Craft (from Georgia, in 1848), and Sojourner Truth, born in upstate New York as Isabella Baumfree, who had left her master in 1826 just before New York’s emancipation law took effect (“I did not run off, for I thought that wicked, but I walked off, believing that to be all right”) to become an itinerant evangelist, first for women’s rights, then for abolition. The antislavery meeting—especially in New England and across the evangelized districts of upstate New York—was becoming a secular communion in which the sacramental moment arrives when a flesh-and-blood runaway stands before the congregation as a living crucifix and begins to speak.

3.

But it was one thing for a community to affirm its faith to itself and quite another to attract new converts. If fugitive slaves and their allies were to advance the work, in Bibb’s words, of “abolitionizing the free States,” they would have to turn some significant portion of northern whites from indifference to commitment.

More daunting still, even if northerners could be warmed to the cause, there could be no final victory over slavery until it was repudiated by its practitioners in the South. Former slaves were thus recruited to campaign for “moral suasion”—the long, slow process of persuading slaveholders, one by one, soul by soul, to repent.

To modern ears, such a strategy will sound hopelessly naive. Anyone who has lived through the second half of the twentieth century is accustomed to thinking first of government—courts, Congress, presidents—as agents of change. Change the law, we want to believe, and hearts and minds will follow. Through the application of federal power, we have indeed witnessed the destruction or at least the modification of social norms that not so long ago seemed intractable—de jure segregation, laws against miscegenation, formal barriers to equal rights for gay people, stigmatization of abortion.

But in antebellum America, the case was entirely different. Slavery could not be legislated away by Congress or ruled out of existence by the Supreme Court. The “slavocracy” (the derisive name applied to the southern ruling class by its enemies) held an effective veto in the federal government, and even if northern influence were to grow over Congress, the Court, and the presidency, as Calhoun and others feared, federal jurisdiction over slavery was foreclosed by the Constitution, which guaranteed to the states the right to control their internal institutions.

It was therefore quite possible to hate slavery while believing that the only route to abolition was through the spiritual conversion of those who owned slaves. Despite efforts to censor abolitionist speech and writing, the South could no more seal its borders against incoming words than against outgoing slaves. Writings by and about fugitive slaves were thus deployed in the hope of touching the slave owners’ hearts. In this sense, these writings were literary precursors of the televised images broadcast a century later during the civil rights movement—police dogs unleashed on protesters, white adults spitting at black schoolchildren—on the premise that decent people everywhere would recoil from what they saw.

In 1838, the argument for moral suasion was made by Edward Beecher, brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe and friend of the murdered Elijah Lovejoy. Beecher described slavery as an “organic sin,” by which he meant a sin that permeates the body politic so completely that it cannot be cured by targeted excision but must be overwhelmed with an infusion of love. He had no illusion about how soon the cure would come. “Organic sins,” he wrote, “are the most difficult of all to reform, because before they can be reformed, there must be disseminated through the body politic such an amount of knowledge and moral principle, as shall induce a whole community, or at least a majority of them, to concur in abolishing by law the sinful system.” To this end, the words that fugitives spoke on the stage had to be moved to the page. And so one way to trace the growth of the antislavery movement is to follow the rising arc of autobiographical slave narratives published as books—four in the 1820s, nine in the 1830s, twenty-five in the 1840s, thirty-three in the 1850s.

Stories by and about fugitive slaves also appeared in the antislavery press. Early instances included the Genius of Universal Emancipation, published briefly first in Tennessee, then, beginning in 1824, for fifteen years in Baltimore by the Quaker Benjamin Lundy, assisted by Garrison, who publicized whippings and lynchings in a column called the “Black List.” The first African American newspaper, Freedom’s Journal, appeared in New York, in 1827, edited by Samuel Cornish, a Delaware-born free black man and founding member of the American Anti-slavery Society, and John Russwurm, born in Jamaica to an enslaved mother and an English father, who supported the American Colonization Society and moved in 1829 to what was to become Liberia. Like all papers in its time, it functioned in part as a news-gathering service for local readers, reprinting articles from other papers and excerpting speeches by public figures on issues of the day, notably the fugitive slave question.

By the 1830s, the antislavery press, led by Garrison’s Liberator (founded in 1831), was spreading throughout the free states and had even established outposts in the upper South. As the number of papers devoted to the cause rose, violence against them grew apace. In 1835, the Standard and Democrat, published at Utica, New York, was attacked by a mob. In 1838, the Philadelphia office of the Pennsylvania Freeman, edited by Whittier, was trashed and burned. Upon leaving Philadelphia, Whittier took up the editorship of the Middlesex Standard, published at Lowell, Massachusetts, which ran many stories about runaways, including one who stowed away aboard a vessel carrying cotton from Mobile to Providence, until, upon being discovered, he threw himself into the sea.

In 1845, pro-slavery thugs drove the True American, edited by Cassius Clay in Lexington, Kentucky, out of the state despite his having fortified the office with a cache of rifles and gunpowder. Before Elijah Lovejoy moved the Observer in 1837 from St. Louis to the illusory safety of Alton, Illinois, it had already been attacked three times. When the mob made a fourth assault, it was Lovejoy’s death, not the death of the paper, that made the event national news.

In an age when part of an editor’s job was to spit vitriol at his competitors, violence—most of it having nothing to do with slavery—was routine. Duels over personal insults were so common that the editors of the Vicksburg Sentinel fought four before the Civil War. It was not unusual for aggrieved readers to storm the offices of papers by which they were offended, in order to conduct “censorship by cudgel and horsewhip.”

Writing just a step beyond credibility, Mark Twain caught the tone of the times in a sketch (written after the Civil War) of a Tennessee newspaperman who, having shot one of his detractors, leaves a note of advice for his successor before skipping town:

Jones will be here at three—cowhide him. Gillespie will call earlier, perhaps—throw him out of the window. Ferguson will be along about four—kill him. That is all for today, I believe. If you have any odd time, you may write a blistering article on the police. The cowhides are under the table, weapons in the drawer, ammunition there in the corner, lint and bandages up there in the pigeon-holes. In case of accident, go to Lancet, the surgeon, downstairs. He advertises; we take it out in trade.

Most disputes were petty and local, but it was the abolitionist editors who spread offense quicker and farther than anyone else. Although the Liberator was edited and published in Massachusetts, Garrison was indicted for “felonious acts” as far away as North Carolina. In South Carolina, rewards were posted for the arrest of anyone distributing his paper.

Among the regular features of antislavery papers were stories of fugitives living in the North under threat of recapture. The African Observer, published in Philadelphia (1827–1828), called attention to protections that had been furnished to fugitives in the ancient world by the Mosaic law, pointing out that the Israelites “themselves were fugitive slaves (Exodus, 14:5).” Published in New York from 1833 to 1834, the American Anti-slavery Reporter devoted a pages-long “Chronicle of Kidnappings in New York” to former slaves who, having lived peacefully in the city for years, were seized and thrown into “cells about 7 feet by 3½ with no light but that which straggles through a grating in the door” before being returned to their states of origin, where they were beaten until they named other runaways after whom slave catchers could be dispatched.

The antislavery press also publicized incidents in which blacks who had never been enslaved were seized by kidnappers on the pretext that they were runaways. These papers included the Mirror of Liberty, edited by David Ruggles, leader of the New York City Vigilance Committee, which tried to disrupt abduction attempts by hired thugs who did not much care if they seized a confirmed fugitive or any black person suitable for sale in the slave market back home. Also in New York, the National Anti-slavery Standard ran regular notices about slave escapes throughout the country while remaining prudently reticent about the local network—just then coming to be known as the Underground Railroad—that was helping them travel farther north to New England or Canada. In Boston, Garrison’s Liberator continued publication all the way until the Civil War, running more than two hundred narrative sketches of slave escapes over three decades.

One often hears it said that among the dark novelties of our own time is our easy recourse via some favorite website, or TV news network, or radio talk show to an “echo chamber” where there is nothing to hear but amplified validations of what we already believe. In fact, the case in antebellum America was not so different. There was no such concept as journalistic “balance.” Newspapers did not run Op-Eds with alternative points of view. With rare exceptions such as James Gordon Bennett’s New York Herald—which, like Page Six of today’s New York Post, dispensed gossip and slander with little regard for the political allegiance of its targets—virtually every paper was, first and last, a party organ.

The same array of party alignments was evident among the more intellectually ambitious periodicals. The moderate pro-slavery position—held by people who considered slavery beneficial for both races but who were willing to acknowledge its susceptibility to abuse—could be found in the Southern Quarterly Review, edited in Charleston by a transplanted New Englander. For those convinced of the natural justice of slavery, the journal of choice was DeBow’s Review, published in New Orleans, which gave strident voice to the Calhoun wing of the Democratic Party.

Conservative northerners who disapproved privately of slavery but refrained from denouncing it publicly for fear of disturbing the delicate balance between North and South could subscribe to the North American Review. For intellectuals outraged by slavery but with no practical plan for terminating it, there was the Dial, edited by Margaret Fuller, who, in the summer of 1843, declared that “freedom and equality have been proclaimed” in the United States “only to leave room for a monstrous display of slave dealing and slave keeping.”

4.

For anyone anywhere on the spectrum of antislavery opinion, the first challenge was to refute the idea that slavery was a benevolent institution. Hard as it may be for us to fathom, decades after the Revolution, in a republic founded in the name of human rights, there was no consensus that slavery was outrageous or even anomalous. Speaking in Congress in 1820, Senator Nathaniel Macon of North Carolina made the amiable suggestion that all doubts about its benignity could be dispelled if only his northern colleagues “would go home with me, or some other southern member, and witness the meeting between the slaves and the owner, and see the glad faces and the hearty shaking of hands.”

Through the 1830s, this kind of treacle was avidly consumed, promoted in such pastoral idylls as Swallow Barn, a bestselling book about plantation life by the Maryland Whig John Pendleton Kennedy, published in Philadelphia in 1832. Kennedy, who eventually came to favor compensated emancipation, portrayed the South—at least the upper South—as populated by carefree slave boys whose “predominant love of sunshine” keeps them outside until after dark, always playing, never working, eager for visits from their kindly master, whom they hail “with pleasure” whenever he drops by “to add to their comforts or relieve their wants.” The same picturesque fantasy persisted to and beyond Gone with the Wind (1936), and no doubt lingers today in the minds of people unwilling to admit that they still believe it.

So when former slaves stepped forward to dispute it in person, or in newspapers, periodicals, or books, they were challenging a deeply entrenched myth. In this respect, they were following in the footsteps of British abolitionists who, over the course of the eighteenth century, had sponsored memoirs by former slaves in an effort to convince the nation that enslaved Africans were capable of becoming good English Christians. It was in England that the slave narrative as we now recognize it first took form.

The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, published in London in 1789 and reprinted thirty-six times before 1850, bore a frontispiece showing the author holding the Bible open to the book of Acts (chapter 4, verse 12): “Neither is there salvation in any other, for there is none other name under heaven given among men whereby we must be saved.”

When the genre moved to America, it remained generally true that “the slavery of sin received much more condemnation than the sin of slavery.” In his 1825 memoir, Solomon Bayley, a slave born in Delaware who managed to buy freedom for himself, his wife, and his children, opened his narrative with this confession of faith:

Having lived some months in continual expectation of death, I have felt uneasy in mind about leaving the world, without leaving behind me some account of the kindness and mercy of God towards me. But when I go to tell of his favours, I am struck with wonder at the exceeding riches of his grace. O! that all people would come to admire him for his goodness, and declare his wonders which he doth for the children of men. The Lord tried to teach me his fear when I was a little boy; but I delighted in vanity and foolishness, and went astray. But the Lord found out a way to overcome me, and to cause me to desire his favour, and his great help; and although I thought no one could be more unworthy of his favour, yet he did look on me, and pitied me in my great distress.

Although recent precedents for this kind of writing could be found in eighteenth-century Britain, its roots reached much further back through the long history of Christian confession all the way to such tracts as Thomas à Kempis’s Imitatio Christi (1427), which called sinners to emulate Christ in penitent humility, and John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments (1559) (better known as Foxe’s Book of Martyrs), which recounted the sufferings of believers for whom the price of fidelity was pain and death. Virtually all early American slave narrators prescribed to their readers a strong dose of Christian piety, with only a few declining to fill the prescription for themselves.

One notable dissenter was William Grimes, who, in his Life of William Grimes, the Runaway Slave, Written by Himself (1825)—a book little read in its own time, and still too little known in our own—was as tough on his fellow slaves as he was on his masters. The book seems to have been the unassisted work of Grimes himself, whose sentences no editor would have left unrevised because of both what he said and how he said it. “I have been so hungry for meat,” he wrote, “that I could have eat my mother.”

From his time in Virginia, he recalled how another slave fouled their master’s morning coffee by mixing the grinds with bitter herbs in order to get Grimes—also assigned to kitchen work—blamed and banished to the fields, thereby opening up a house position for her own son. From his time in Georgia, he recalled the “witch” who shared his sleeping space located directly below their master’s. She would “ride” him (he claims she visited his bed only in dreams she sent to him as spells in the night), forcing from him involuntary “noise like one apparently choking or strangling” until his master is provoked to wrath—whether out of disgust, or irritation at being awakened, or jealousy over what was going on in the bed beneath him, he does not say.

Grimes ended his slave career in the possession of a Savannah merchant who, while on holiday with his family in his native Bermuda, allowed him to earn what he could on the wharves and, except for three dollars a week to be collected upon his master’s return, to keep his wages. During those months of quasi-freedom, he was befriended by sailors who took him aboard the brig Casket, where he created a hiding place by cutting a hole within a group of cotton bales that had been lashed together. Having supplied himself with survival provisions—“bread, water, dried beef”—he was confined in this puffy pocket except for nighttime forays onto the open deck until the ship made landfall at Staten Island, whence he made his way to New Haven, Connecticut.

There Grimes embarked on a new life that turned out to be barely better than the life he had left behind. Yale students, pretending to befriend him, plied him with drink in order to amuse themselves with his slurring and stumbling until, his dignity destroyed, he “took the floor and lay there speechless some hours.”* This was a far cry from the standard tale of deliverance to “northern regions, / Where smiles all that is glorious, aye, all / That is beautiful.” As Grimes’s modern editor remarks, “The more he reveals about his life in the North, the more ironically pointless his flight to freedom seems.” His was an early and fearless account of how limited “freedom” in the North could be.

5.

But Grimes, in his candor, was exceptional. By the 1830s, the slave narrative—factual, fictional, or a hybrid of both—was settling into the formula that would define it for decades to come: a pilgrimage story of rising from darkness to light. Most of Grimes’s contemporaries stuck faithfully to the script of what has been called the “liberty plot,” describing the gauntlet of horrors they had been forced to endure—beatings, broken promises, separation of parents from children, enforced illiteracy, sexual abuse—always careful to expunge any trace of bitterness at what had been done to them. Writing in 1837, Moses Roper (whose memoir went through ten editions in twenty years) explained, “I bear no enmity even to the slave-holders but regret their delusions.” In the 1849 book that helped to inspire Harriet Beecher Stowe to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Josiah Henson writes that upon learning that he was to be sold to a New Orleans buyer, he was tempted to kill his master’s son before conscience checked his rage and subdued it into Christian forgiveness. The slave’s self-restraint became a sentimental convention, reaching its apotheosis in the fictional figure of Uncle Tom.

Every teller of a chase-and-escape story knows that all but the most heartless reader will root, at least half-consciously, for the prey to get away. So it was with the slave narratives. They tapped into that place in the human psyche from which dreams arise of being stalked to the verge of disaster—toward the edge of a precipice, into the jaws of some ravenous animal or the clutches of some human brute—just before we wake to the delicious relief of knowing it was all a dream. We want the pursuers to take a wrong turn, to blow a tire, to run out of gas. Think of the harrowing manhunt in Richard Wright’s novel Native Son as police close in on a black teen who has strangled a white girl in a moment of panic, or Fritz Lang’s film M, about a frenzied hunt for a child killer, or any number of films by Alfred Hitchcock (North by Northwest; The Wrong Man; Frenzy), in which the fugitive’s guilt or innocence has little bearing on our allegiance. Whether by luck, or guts, or God’s favor, we want the pursued to get away no matter what set him to running in the first place.

But if runaways had an intrinsic advantage in telling their stories, it was quite another matter to convince the public that they were telling the truth. Most southerners and not a few northerners suspected that the relation between sponsor and fugitive was a form of puppetry. Virtually every published work by a black antebellum writer was a collaboration with a white editor. When Douglass took his story into print in 1845, he had been reciting it at public meetings for the better part of four years, during which he was coached as if he were a novice courtroom witness. “‘Tell your story, Frederick,’ would whisper my revered friend Garrison,” he wrote late in life, investing that word “revered” with something like a sneer. Garrison’s deputy John Collins chimed in with this piece of patronizing advice: “Give us the facts, we will take care of the philosophy.” Yet when the spontaneity of speech gave way to the fixity of print, the facts themselves came into dispute.

Not all slave narratives were edited by committed abolitionists. David Wilson, the lawyer who helped Solomon Northup write Twelve Years a Slave (1853), seems to have been more interested in making money than in advancing the cause. Samuel Eliot, who worked on the first edition of Josiah Henson’s 1849 narrative, entered Congress the following year and promptly voted in favor of the fugitive slave law. But regardless of the political allegiance of the editor, it was obvious that most memoirs by fugitive slaves had been to one degree or another sanitized. For one thing, they were reticent about the fact that slave catchers could get assistance from other slaves swayed by threats of reprisal if they refused to help, or by hope for a reward, or by a grudge against the escapee.

And if the substance of the narratives was trimmed and shaped by their editors, so was their style. Most had a formality that brought the first-person voice into conformity with prevailing norms of literary diction. They alluded to writers unlikely to be known to someone who had struggled to gain literacy (Henson did not learn to read until the age of forty-two) and employed phrases that echo or anticipate other works by the same editor. They lacked the unrehearsed immediacy of oral histories like that of one runaway who, in an interview with William Still, leader of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee, described his master as “a speckled-faced—pretty large stomach man, but . . . not very abuseful.” This sort of freewheeling language was rare in the published narratives, which tended to have a certain forced propriety as if a friendly censor had cleaned up the infelicities and gaffes. When Lydia Maria Child, who guided Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861) into print, assured readers that “with trifling exceptions both the ideas and the language” were the author’s own, the claim itself seemed a trifle defensive.

One text that seemed especially dubious was the Narrative of James Williams, published by the American Anti-slavery Society in March 1838 with a preface by Whittier. As lurid as anything in Quentin Tarantino’s film Django Unchained (2012), the book described the Alabama from which Williams escaped as a bloodbath world in which fugitives are tracked and torn by vicious dogs. After finishing their murderous work, the proud hounds trot back, “jaws, heads, and feet” dripping red, eager to lead their handlers to what’s left of the prey, whose “entrails [are] clinging to the old and broken cane” through which the victim has made his frantic run.

It turned out that Williams had changed locations and names (including his own), conflated places and dates, and laced his story with exaggerations and outright fabrications. It was all done, no doubt, from a mix of motives: to please his interviewers, to protect himself from slave owners’ agents posing as Underground Railroad conductors (a common practice), and, perhaps, to achieve renown that could be translated into money. Southerners, led by J. B. Rittenhouse, editor of the Birmingham Alabama Beacon, leaped to attack the book with alliterative fury as a “foul fester of falsehood.” In October 1838, seven months after it had been published, the American Anti-slavery Society disavowed it.

We now know that despite his embellishments and use of false names, most of what Williams wrote was substantially true. Like all fugitives, once he arrived in the North, he had every reason to be anxious, bewildered, and uncertain of whom to trust. He was held in semi-voluntary detention in a New York City safe house, where he was interrogated by a trio of antislavery luminaries—Whittier, the Boston Unitarian Charles Follen, and James Birney, a former Alabama slaveholder who had left the South to become an outspoken abolitionist in the North. His hosts—sometimes they must have seemed to him not so different from captors—checked and rechecked his stories against maps, against the letter of introduction sent ahead of his arrival by the Underground Railroad conductor who had sheltered him near Philadelphia, and against Birney’s personal knowledge of the terrain over which Williams claimed to have fled.

Even when news arrived that slave catchers were on their way, accompanied by a black man who could identify him, the interrogation continued—giving him every reason to tell his questioners what they wanted to hear. As Renata Adler has remarked about refugees fleeing today’s Middle East, “questions of identity, national origin, even date of birth” are bound to provoke “an instinct, perhaps common to all refugees from dangerous situations, to lie.” Fugitives have always had reason to fear that telling the truth and nothing but the truth raises their risk of deportation.

6.

It was Douglass who broke through to a new level of public trust. With prefaces by Garrison and Phillips, his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself, was published by the American Anti-slavery Society in 1845. At first, its veracity, too, was questioned, notably by a neighbor of Thomas Auld’s, A. C. C. Thompson (short for his rather ungainly full name, Absalom Christopher Columbus Americus Vespucius Thompson), who, in a letter to the Delaware Republican, denounced Douglass’s book as a pack of lies.

In fact, by defending the honor of principal figures in Douglass’s Narrative while confirming their identities, Thompson unwittingly enhanced its credibility, for which Douglass thanked him in the Liberator.* “You, sir,” Douglass wrote, “have relieved me. I now stand before both the American and British public, endorsed by you as being just what I have represented myself to be—to wit, an American slave. . . . You thus brush away the miserable insinuations of my Northern pro-slavery enemies, that I have used fictitious, not real names.” Meanwhile, the book was commended by, among others, Margaret Fuller, who praised it in Horace Greeley’s New-York Tribune in June 1845, and within five years it had sold some thirty thousand copies, making its author nationally and internationally famous.

But fame, for a fugitive slave, was a dangerous thing. It made him an enticing target for slave catchers. Still legally the property of a Maryland slave owner, Douglass accepted advice from friends that he seek “refuge in monarchical England from the dangers of republican slavery.” In Britain, he found himself still more in demand, and discovering that “it is quite an advantage to be a ‘nigger’ here,” he promised, with due mordancy, that lest he not be “black enough for the british taste,” he would keep his “hair as wooly as possible.”

Going abroad did not close the gap between what his audiences wanted and what he wanted to give them. “Accounts of floggings,” as his biographer William McFeely has remarked, were among “the most sought-after forms of nineteenth-century pornography (disguised in the plain wrapper of a call to virtuous antislavery action).” Douglass recoiled from this kind of prurience but nevertheless took advantage of it. “I do not wish to dwell at length upon . . . the physical evils of slavery,” he said. “I will not dwell at length upon these cruelties”—yet he never stopped speaking and writing of “the whip, the chain, the gag, the thumb-screw, the blood-hound, the stocks, and all the other bloody paraphernalia of the slave system.”

As his fame grew, he became less a scripted witness and more his own man—a man to whom antislavery activists and, eventually, mainstream politicians turned for advice and for the sheer prestige of his affiliation. In the enlarged version of his memoir published in 1855 as My Bondage and My Freedom, he wrote, “It was slavery, not its mere incidents—that I hated.” There was, of course, nothing “mere” about the physical abuses he had witnessed and endured, but he bristled at being regarded as a freak survivor whose intellect was doubted even by those who swooned at his afflictions.

In November 1846, while Douglass was in Britain, Thomas Auld sold him in absentia, for unclear reasons, to his brother Hugh for $100. Within a month, Hugh accepted an offer of 150 pounds sterling (more than $1,000 in nineteenth-century dollars) from Douglass’s English friends, who had raised the funds to buy his freedom. In December 1846, Auld filed a deed of manumission in the Baltimore County courthouse. In an early sign of the tension with Garrison that would soon become estrangement, Douglass discovered upon his return to the United States that some of his “uncompromising antislavery friends” disapproved of his having allowed his liberty to be paid for, thereby, they thought, consenting to have his freedom bought as if it were a house or a horse rather than the stolen birthright of a man.

Publication of the Narrative made Frederick Douglass, as one scholar writes with stinging accuracy, “the most famous black exhibit of the nineteenth century.” Whenever he appeared on a speakers program, crowds poured out to hear him, including large numbers of women, at whom he took special aim. Beginning his book with the piteous confession that he could barely remember his own mother, he told how she was forced to live miles away, traveling on foot by night to visit her child under threat of flogging if she should fail to return to work in the fields by sunrise. “I do not recollect of ever seeing my mother by the light of day. She was with me in the night. She would lie down with me, and get me to sleep, but long before I waked she was gone.”

Here was a version of what the literary scholar Northrop Frye has called the “theme of the hunted mother.” A figure in Western literature from medieval romance to the nineteenth-century novel, she appears in one form or another in almost all the slave narratives, reaching her American apotheosis in Uncle Tom’s Cabin when Eliza flees the slave catchers with her child clasped to her breast. Hers is the story of Anna’s failed suicide as told by Jesse Torrey in 1817. Twenty years later, she appears in the diary of John Quincy Adams, who describes the anguish of Dorcas Allen, awaiting sale in a slave pen in Alexandria, who killed two of her four children because “if they had lived she did not know what would become of them.” We meet her again in Margaret Garner (the model for Sethe in Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved), who, in 1856, cut the throat of her daughter as slave catchers closed in on them.

Douglass’s treatment of the theme was both heartfelt and deft. “Never having enjoyed . . . her soothing presence,” he writes of his own mother, “I received the tidings of her death with much the same emotions I should have probably felt at the death of a stranger.” The message was clear. Slavery robs mothers of their motherhood and thereby stunts the souls of their sons. It turns motherless black boys into heartless black men. Beware of the dark millions headed toward manhood: they will grow into potency with no sense of empathy or love. Slavery is a factory for manufacturing monsters. For your own sake, Dear Reader, you had better curtail production!

But if Douglass portrayed himself as a force to be feared, he was also shrewdly pacifying. He told his life as a quintessentially American boy-makes-good story—an inspirational tale of beating the odds, of rising from low circumstances to high station. Even as he recalled such radicals as David Walker—who, in his Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World (1829), had urged slaves to rise up against their masters—he wrapped himself in the mantle of revered patriots like Ben Franklin, who, in his own memoir, had recounted his life as a journey from servitude to independence. “In coming to a fixed determination to run away,” Douglass declared, “we did more than Patrick Henry, when he resolved upon liberty or death.” I’m not looking for vengeance, he seems to say, but—just like you, my fellow Americans—I’m looking for opportunity. No work is too low for me as long as it is paid work. “I found employment, the third day after my arrival” in New Bedford,

in stowing a sloop with a load of oil. It was new, dirty, and hard work for me; but I went at it with a glad heart and a willing hand. I was now my own master. It was a happy moment, the rapture of which can be understood only by those who have been slaves.

Douglass played with the fire of fear, but his message was ultimately palliative: white people will have less reason to fear black people if slavery is abolished than if it is perpetuated. And like so many of his predecessors, he cast his story as a “glorious resurrection . . . from the tomb of slavery, to the heaven of freedom.” In all these respects, he presented himself, as his friend James McCune Smith remarked, as a “Representative American man—a type of his countrymen.”

7.

In 1845, the same year that saw the publication of Douglass’s memoir, the antislavery clergyman Theodore Parker, who had been reading slave narratives as they rolled off the presses, declared them “the one portion of our permanent literature . . . which is wholly indigenous and original.” America’s distinctive institution, slavery, had at last inspired a distinctively American literary form.

Parker was writing at a time when American writers were defensively sensitive to the charge that even their best efforts were weak imitations of British models. It was a time, as Melville complained, of “literary flunkeyism towards England.” In this sense, Parker was right that the slave narrators were stepping into a literary void.

There was another sense, too, in which he was right—and shockingly so. Most of the white antebellum writers who have since achieved the status of classics—Hawthorne, Poe, Dickinson, Emerson, and Whitman (until the 1850s)—were amazingly adept at averting their eyes from what Theodore Weld, in a compendium of damning facts published in 1839, called American Slavery as It Is. One must strain to find a single line referring to slavery in all of Dickinson’s poetry. When Whitman wrote about slavery, he treated it essentially as a white man’s problem. Hawthorne reacted to it as if, catching a whiff of some unpleasant odor while out on a stroll, he pauses for a clearing breeze before proceeding on his way. Slavery, to his mind, was “one of those evils which divine Providence does not leave to be remedied by human contrivances, but which, in its own good time, by some means impossible to be anticipated, but of the simplest and easiest operation, when all its uses shall have been fulfilled, it causes to vanish like a dream.” There is a long, straight line between this genial call for patience in 1862 and Martin Luther King’s great speech of 1965 delivered after marching from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, in which he asks white America, “How long . . . ? How long?”

Writing contemporaneously with King, one literary scholar called it “the shame of American literature” that “our authors of the 1830s and 1840s kept silent during the rising storm of debate on the slavery issue.” He, too, was right. Anyone hoping to learn about antebellum America by reading America’s classic white authors must read very closely to notice that slavery existed at all. In Hawthorne’s fiction, the closest thing to a black person was an edible treat displayed in a shopwindow: a gingerbread cookie in the shape of Jim Crow.

Among the major antebellum white writers, only Melville acknowledged the scope and horror of slavery, and even he wrote of it obliquely. In Moby-Dick (1851), after a boat pursuing a harpooned whale abandons the chase in order to pluck from the sea the black cabin boy, Pip, who has fallen overboard, he is warned that he won’t be rescued a second time, because “a whale would sell for thirty times what you would, Pip, in Alabama.”* Not until his 1855 novella, Benito Cereno, about a shipboard slave revolt, did Melville confront slavery directly, and then he did so with exceptional literary tact—refusing to presume that he could write from within the unknowable experience of a black African shipped to his doom. So he tells the story from the naive point of view of a white seaman and leaves the ringleader of the insurrection “voiceless” to the end.

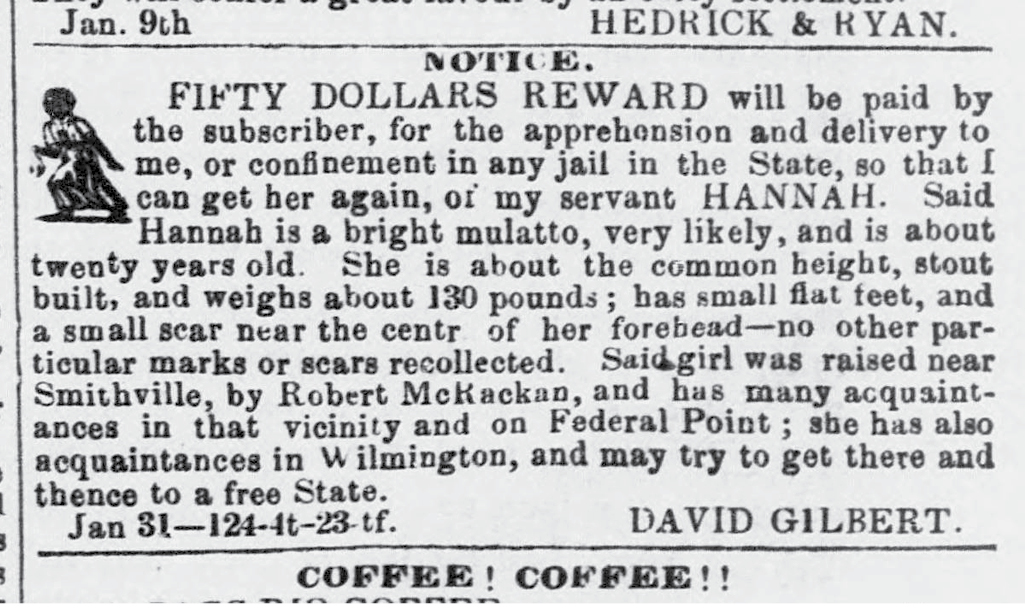

In giving voice to people long silenced, the fugitive slave narratives were therefore exactly what Parker said they were: “wholly indigenous and original.” They did, moreover, what literature rarely does: they moved public opinion. At the very least, they made it more difficult to browse through the runaway newspaper ads without recognizing them for what they were: “an ever-rolling, self-generating flood of evidence, which damned the slave owners out of their own mouths.”

It should not be surprising that these books have lost the urgency they had for antebellum readers. They were written at a time of emergency. Today they are history books. When they were written, they were constrained within the seemly norms of nineteenth-century expression. Today they must compete with such films as Tarantino’s Django, or Steve McQueen’s adaptation of Solomon Northup’s Twelve Years a Slave, in which we see every gash in glistening color and hear every smack of the lash in Dolby sound. When they were first published, they were weapons in a war just begun. Today they belong to a vast literature devoted to every aspect of the slave system—proof, in one sense, of how far we have come, but evidence, too, of the impassable gulf between antebellum readers whom they shocked by revealing a hidden world and current readers, for whom they are archival records of a world long gone. Consigned to college reading lists, the slave narratives, which were once urgent calls to action, now furnish occasions for competitive grieving in the safety of retrospect.

Perhaps the sense in which they remain most alive is in their capacity for literary provocation. Twain’s great novel The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) is in large part the story of a fugitive slave, Jim, fleeing in the company of a white boy conflicted over whether to protect or betray him. Writers today continue to turn to the slave narratives—some in a spirit of somber emulation (Toni Morrison, Beloved [1987]), others with inventive exuberance (Charles Johnson, Oxherding Tale [1982], Colson Whitehead, The Underground Railroad [2016]). Consider, among the latter, James McBride’s rollicking novel The Good Lord Bird (2013), in which Douglass is a randy badass who can’t keep his hands off a fugitive slave boy posing—apparently convincingly—as a girl in order to elude the slave catchers. Fooled by the cross-dressing boy (Henry now calls himself Henrietta), the great man sidles up to him, commencing a slow grope while whispering, “My friends call me Fred,” then rising into a speech in which seduction takes the guise of instruction:

They know not you, Henrietta. They know you as property. They know not the spirit inside you that gives you your humanity. They care not about the pounding of your silent and lustful heart, thirsting for freedom; your carnal nature, craving the wide, open spaces that they have procured for themselves. You’re but chattel to them, stolen property, to be squeezed, used, savaged, and occupied.

Now the boy starts to worry:

Well, all that tinkering and squeezing and savaging made me right nervous, ’specially since he was doing it his own self, squeezing and savaging my arse, working his hand down toward my mechanicals as he spoke the last, with his eyes all dewy, so I hopped to my feet.

This kind of writing defies the dictates of martyrology by which the antebellum slave narratives were controlled and confined. Perhaps the fact that a black writer today can write about a black icon like Douglass with such jaunty irreverence is a sign that we are finally getting past the squeamish pieties that are another form of the condescension he faced, from allies as well as enemies, in his own time.

The Douglass of the memoirs is a paragon. There is little trace in him of the man who must sometimes have been petty, impulsive, and vain—not a piece of property to be utilized in one way or another but, as one putative friend complained, a “haughty” and “self-possessed” man with the low as well as exalted desires that constitute freedom. To pretend otherwise is to treat him once again as less than human.

Surely, then, there are grounds for dissent from Parker’s judgment that the slave narratives marked the first maturity of America’s literature. No one can doubt the power with which they testified against the inhuman institution. But no one can say that they dove deep into the contradictions of the human heart. They were truncated stories of impossibly virtuous victims. They were more than propaganda but less than literature. They were populated by stock types—the decent but weak master, the jealous mistress, the self-hating house slave, the vicious overseer (forerunner of Simon Legree) who knows that he stands in the social hierarchy barely above the slaves he despises. As one sympathetic critic has said, they “rather breathlessly review the subject’s life from a single unchanged perspective, that of a condition known as Freedom.”

Runaway advertisement, 1857

In fact, they tend to stop with the attainment of freedom, before human problems—love unrequited, desire thwarted or sated, fear of oneself as well as of others—begin. In this sense they were not so far from the stock newspaper images they were meant to refute, brilliantly echoed by Kara Walker in her featureless silhouettes:

Alabama Loyalists Greeting the Federal Gun-Boats, Kara Walker, 2005

Of course there were exceptions. In William Wells Brown’s memoir, we encounter his shame at colluding with slave dealers when, compelled to prepare older men for sale, he shaves them and applies boot black to their graying stubble in order to make prospective buyers think they are younger than they really are. Brown, who cautioned that “slavery can never be represented,” found ways to convey the pitiless indignity to which it subjected all who came within its reach:

I was ordered to have the old men’s whiskers shaved off, and the grey hairs plucked out, where they were not too numerous, in which case [the slave owner] had a preparation of blacking to color it, and with a blacking-brush we would put it on. . . . After going through the blacking process, they looked ten or fifteen years younger; and I am sure that some of those who purchased slaves . . . were dreadfully cheated, especially in the ages of the slaves which they bought.

In Solomon Northup’s Twelve Years a Slave, there is a heartrending account of his master ordering him to whip a slave girl for whom the master feels a toxic combination of rage and lust:

Turning to me, he ordered four stakes to be driven into the ground, pointing with the toe of his boot to the places where he wanted them. When the stakes were driven down, he ordered her to be stripped of every article of dress. Ropes were then brought, and the naked girl was laid upon her face, her wrists and feet each tied firmly to a stake. Stepping to the piazza, he took down a heavy whip, and placing it in my hands, commanded me to lash her.

After endangering himself by hesitating, Northup lays into her with what seems a good imitation of his master’s zeal, forcing us beyond the position of a spectator watching cruelties that we cannot imagine perpetrating or suffering, into wondering how we would behave—surely, we know the ugly answer—if compelled to choose between doing the master’s bidding and diverting the master’s wrath to ourselves.

Such moments, foreign yet familiar, are literary moments because, as much as they are about the men and women who wrote them, they are also about us.