2

Setting Global Standards

Besides being the ‘silver bullet’ bringing much needed growth and jobs to the EU and the US, a second argument for TTIP is that it will allow both parties to continue setting the standards for the global economy in the twenty-first century. Arguments of a strategic, geo-economic and geopolitical nature have been increasingly prevalent, accompanying the more traditional economic case for FTAs of enhanced efficiency, increased income and additional employment.1 This ‘setting global standards’ discourse serves a double function. By emphasising the prospect that China and other emerging economies might in the near future be masters of global economic governance if the EU and the US fail to cooperate, (progressive) sceptics of TTIP are being accused of contributing to the West’s demise. At the same time, by invoking the idea of China as ‘the other’, the impression is strengthened that the regulatory cultures of the EU and the US are rather similar, paving the way for regulatory cooperation. This chapter critically examines the assumptions and consequences of this narrative.

Even before the financial crisis erupted in 2008, which seemingly harmed developed economies more than emerging economies, there had been a lot of talk about the (economic) ‘decline of the West and the rise of the rest’ (Zakaria 2009). In particular, the BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India and China) – a term coined in 2001 by Jim O’Neill, then of Goldman Sachs – have been seen as posing a challenge to the postwar dominance of the US and (later also) the EU over the global economy. Since then, there has been an increasing awareness in American and, especially, European policy circles of their declining hold over global economic governance. This view has been reinforced by the failure to conclude the Doha Round in the face of resistance from India and (to a lesser extent) China. All of this has led key political actors on both sides of the Atlantic, such as Secretary of State Hillary Clinton or the then North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) Secretary-General Anders Fogh Rasmussen, to refer to TTIP as an ‘economic NATO’ (van Ham 2013: 2; Rasmussen 2013).

The logic behind this argument runs as follows. Only by sticking together can the EU and the US counter their slide into economic and geopolitical irrelevance. A ‘Transatlantic Common Economic Space’, as Barroso (2014) referred to it, with common norms and rules that would cover nearly half of the world’s GDP and one-third of the world’s trade, would enable Europeans and Americans to continue setting the rules of globalisation. It is ‘now or never’, because, in only a couple of years’ time, China will be the largest economy in the world and the global rule-setter, with the once powerful Western governments relegated to becoming rule-takers. This narrative has only emerged as more central to advocacy in favour of TTIP as the world, and Europe in particular, has seemingly become a more insecure place, with turmoil both at the EU’s southern border with the Arab world and in its eastern neighbourhood, given conflict with Russia over Ukraine. In this turbulent geo-economic and geopolitical environment, advocates of transatlantic economic integration point to the relative homogeneity of European and American interests and values, which should not be disrupted by the relatively small differences of opinion of the past (or those emerging now in the context of the TTIP negotiations).

This second key narrative of ‘setting global standards’ in the face of the rise of the likes of China thus provides an additional argument to convince those who are rather sceptical about the ‘economic gains’ narrative discussed in the previous chapter. The more the economic rationale, and TTIP in general, has been contested, the more this second, geo-economic justification has been drawn upon. It is a forceful one, particularly because there is a thinly veiled threat directed at those who fear that TTIP would negatively affect the quality of social, environmental or public health regulation (especially in the EU), arguably the key concern of critics (see chapter 4). The alternative to cooperating across the Atlantic now, proponents warn, is that standards will be decided within a couple of years by China, which is far less concerned about such matters as social and environmental protections. ‘Is that what you want?’ seems to be the subtext.

This narrative appears to hold some sway among key policymakers. In the EU, many Social Democrats, who have mixed feelings about TTIP, are crucial to securing a majority in the European Parliament in favour of the agreement and are also in government in a number of important Member States, such as France, Italy and Germany. In Germany, there has been an intense debate about TTIP, especially with regard to food safety and ISDS (see chapters 3 and 4). But, in February 2015, the German Social Democratic Economy Minister Sigmar Gabriel spoke out strongly in favour of TTIP – revising a more hesitant position taken earlier on – saying that failure to agree an ambitious deal would cost the EU influence in the global economy (Fox 2015). Responding to opponents of Trade Promotion Authority within his own Democratic Party, President Obama has also increasingly invoked this argument.

In the remainder of this chapter, we scrutinise this geo-economic narrative. We briefly review debates on the US and EU position in the post-Cold War global political economy. These discussions have gone from speaking of US-dominated unipolarity, to an EU soft power-based challenge of US hegemony, to, most recently, the notion that both Western powers are in decline with respect to emerging markets. It is this latter perception that has led to the conclusion that the EU and the US need to join hands in shaping global economic governance. Being able to set the global rules here is a particularly important objective for the EU, which, in the absence of developed military capacity, considers its ‘market power’ to be its main source of strength in global politics. We warn, however, that EU–US regulatory cooperation will not automatically result in the setting of global standards, as TTIP’s champions claim.

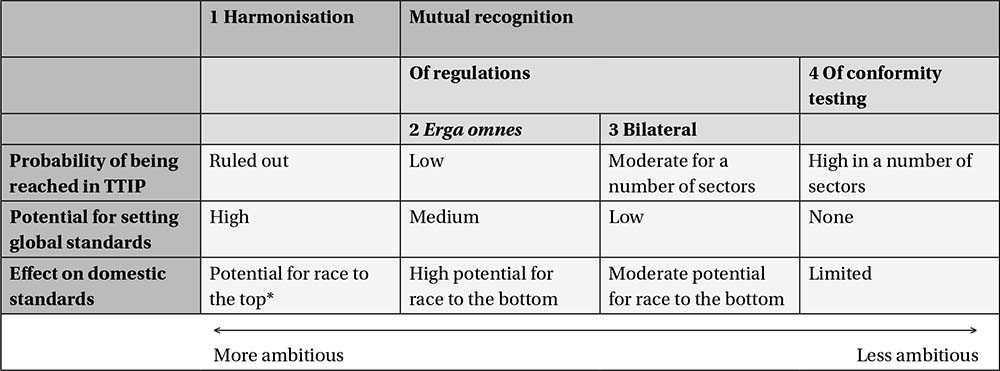

Notably, we draw an important distinction between the consequence of harmonisation and the mutual recognition of regulations when it comes to the standard-setting capabilities of TTIP. The latter not only carries the risk of setting off a ‘race-to-the-bottom’ dynamic in terms of the levels of risk regulation across the Atlantic but will also provide little or no incentive for third countries to align their norms and rules with those in the EU and the US. There is also a second problem with the ‘setting global standards’ argument in favour of TTIP. Key to the narrative of transatlantic regulatory leadership is emphasising similarity in the regulatory objectives and philosophies on both sides of the Atlantic, in contrast to the view in the first decade of the twenty-first century that the EU and US regulatory philosophies fundamentally conflict with each other. Belittling the distinctiveness of the EU’s approach to market regulation might decrease rather than promote, we caution, the prospect of ambitious global standards in the future.

American decline and disillusion with market power Europe

The view that the US and the EU currently need to collaborate to prevent China from becoming the next regulatory superpower is presented as common sense. In the US, this resonates with the idea of American hegemonic decline in the global economic and political system that has been around through several waves of ‘declinism’ (Huntington 1989). While in the early Cold War era the fear was that the US was losing strength relative to the Soviet Union, Japan emerged as the main commercial bogeyman in the 1970s and 1980s – with concern over the relative competitiveness of the US compounded by persistent trade deficits. In contrast, the period after the end of the Cold War, and certainly after the Japanese asset price bubble of the 1990s and its subsequent (long) lost decade, has been defined as the American unipolar era – a moment when its model of liberal capitalism triumphed over alternatives. The dominant view, however, is far less sanguine these days, with the ‘Chinese threat’ being taken more seriously than previous challenges to US power: ‘this time is (allegedly) different’ to previous episodes of relative decline, among other things because the US’s traditional allies are also losing (economic) clout at around the same time (Rachman 2012).

European integration has always been pursued (at least partly) with an eye to achieving equivalence in economic and political power with the US. And for a decade or so, from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s, EU policymakers and some observers – looking beyond military capabilities – seemed to agree that the EU’s ‘soft power’ would allow it to lead in the twenty-first century. This was in part because of the distinctiveness of its geopolitical and socioeconomic policies from those of the US. But the protracted effects of the economic crisis have shattered hopes of a European century based on such normative leadership.

In what follows, we unpick the narrative that presents transatlantic cooperation as a matter of course to counter Western decline. We show how, during the brief period where there was optimism about the EU’s regulatory or market power, it was seen as a counterweight to the US rather than as a likeminded partner, as in the discourse surrounding TTIP. We then challenge the idea that transatlantic regulatory cooperation would automatically translate into continued EU–US global leadership.

Shared values?

How things change. While today EU and US leaders emphasise the importance of partnership, only a decade ago the transatlantic relationship was strained over disagreements about the war in Iraq and how to deal with terrorist threats more generally, as well as about the urgency of and the way to fight climate change or the right approach to protect citizens against uncertain environmental and food safety risks through the application of the ‘precautionary principle’ (the notion that regulators should adopt measures even in the absence of unambiguous scientific evidence of risk). The EU and the US were engaged in fierce disputes before the WTO Dispute Settlement Body on the EU’s ban on hormone-treated beef, chlorinated chicken and a de facto ban on GMOs. In the same period, the US State Department lobbied heavily against the EU’s new (and very strict) system for the regulation of chemicals (REACH), as well as against similar strict regulations on recycling obligations for electrical and electronic equipment (the Directive on Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment [WEEE]) and bans on hazardous substances in electrical and electronic equipment (the Restriction of Hazardous Substances Directive [RoHS]). In addition to the Kyoto Protocol on climate change, the US had failed to ratify a number of international environmental agreements championed by the EU, such as the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, the Basel Convention on Hazardous Waste, the Rotterdam Convention on Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides, and six of the eight core labour conventions of the International Labour Organisation. Reflecting on such developments, Robert Kagan famously opened his book Of Paradise and Power (2004: 3) with the words ‘[i]t is time to stop pretending that Europeans and Americans share a common view of the world, or even that they occupy the same world.’ This divergence between the EU and the US coincided with a period of self-assurance on the European side about its ability to influence the world through lofty norms and rules.

After the perceived success of the new ‘euro’ currency and the ‘big bang’ Eastern European enlargement of 2004, and notwithstanding the rejection by the French and Dutch electorates of the Constitutional Treaty, there was much confidence about the European integration project (Cafruny and Ryner 2007). It is indeed difficult to imagine today, after just over five years of economic, political and social crisis in the EU (and the euro area in particular), that the first decade of the twenty-first century was marked by considerable enthusiasm about the power and prospects of the EU – if not amid the general public then at least among a number of important policymakers and political pundits. One of the most talked-of books in international politics of the period was Mark Leonard’s Why Europe Will Run the 21st Century (2005), which spoke of the EU’s ability to influence the rest of the world through its soft, regulatory power. The year after, the then Belgian Prime Minister Guy Verhofstadt published The United States of Europe (2006), pleading for a more deeply integrated EU that could leave its mark in a globalised world. The American Ambassador to the EU at the time, Rockwell Schnabel, declared wistfully, ‘[l]et’s face it – you have to deal with them. They have the power of that Market’ (Fuller 2002). Even The Economist (2007), not always known for its Euro-enthusiasm, featured the following headline in 2007: ‘Brussels rules OK: how the European Union is becoming the world’s chief regulator’. In this vein, the investigative journalist Mark Shapiro’s book Exposed: The Toxic Chemistry of Everyday Products and What’s at Stake for American Power (2007) argued that the US was failing to protect its citizens from dangerous substances and products in the way the EU was doing and was therefore rapidly losing its (soft) power to shape the world.

Academics have touted the EU’s regulatory power for even longer. As far back as 1995, David Vogel argued that the EU, thanks to its large internal market and its relatively high level of product regulations (especially with regard to environmental protection), was able to influence rules beyond its borders (Vogel 1995). Ian Manners (2002) subsequently coined the term ‘normative power Europe’ to make sense of the European Union’s role in the world, which is largely built on its ability to change perceptions of what is normal in world affairs. His seminal article on the subject was recognised by then European Commission President Barroso as one of the most influential works on the EU of the previous decade, testifying to the hold it had on EU officials’ self-perception. More recently, Chad Damro has argued that ‘the EU may be best understood as a market power Europe that exercises its power through the externalization of economic and social market-related policies and regulatory measures’ (2012: 682, emphasis added). This power is determined by the size of the EU’s market and its institutional abilities to adopt and externalise ambitious rules, together with the support of interest groups to spread norms globally.

EU officials have, for some time, been conscious of the Union’s ability to export its rules, values and model abroad. In 2005, the European Commission published a Communication on ‘European Values in a Globalised World’, where it explicitly differentiated the ‘European model’ from others in the rest of the world, including the US, and noted that ‘European citizens have greater expectations of the state than their equivalents in Asia or America’ (European Commission 2005: 4). In 2007, in a document on the external dimension of the Single Market, the European Commission (2007b: 2, 5, 8) wrote that, ‘[i]n many areas [...] the EU is looked upon as a regulatory leader and standard-setter’, with the Single Market being ‘a tool to foster high quality rules and standards’. It also identified ‘a window of opportunity to push global solutions forward’.

However, with the crisis and increasing competition from emerging markets, this confidence seems to have waned in recent years, in many ways paving the way for greater transatlantic cooperation. The focus in Europe has increasingly moved away from ‘exporting rules’ towards the imperatives of boosting ‘competitiveness’, which had already become an ever more central concept in EU policymaking since the 2000 Lisbon Agenda and its reinvigoration in the middle of the decade. In the EU’s Single Market Act of 2010, the Single Market was perceived less as an instrument to set global rules and more as a ‘base camp that allows European businesses to prepare themselves better for international competition and the conquest of new markets’ (European Commission 2010a: 17). As an NGO campaigner remarked sharply in 2013, ‘the political priority has gone from saving the planet to saving your job’ (Milevska 2013).

The crisis has indeed hit the EU hard, not only in purely economic terms but also when it comes to how policymakers perceive the EU’s position in the world. As is written in the preface of the successor to the Lisbon Agenda, the new overarching ten-year strategy for the EU entitled ‘Europe 2020’, ‘[t]he crisis is a wake-up call, the moment where we recognise that “business as usual” would consign us to a gradual decline, to the second rank of the new global order’ (European Commission 2010b: 2). EU leaders’ vision since the crisis is increasingly that the continent has to become more competitive to survive, and thrive, in the ‘global race’. What in the previous decade were still seen, with some pride, as distinctive futures of the European model are now often depicted as an unaffordable drag on European competitiveness. A mantra tirelessly repeated during the past years, first by Angela Merkel and later by other EU leaders, is that the EU has 7 per cent of the world’s population, 25 per cent of its GDP and 50 per cent of its social spending (cited in The Economist 2013). The implication of these statistics is that the Union can no longer be this generous or it will lose in its competition with emerging economies. EU policymakers should stop being naïve in believing that the emerging powers will keep adopting the EU’s lofty rules and values, it is argued. The distinctive ‘European social model’ has thus been reduced to a burden borne by the EU in the global economic race.

A large number of influential decision-makers in the EU are thus of the opinion that, while the EU may have written some of the rules for globalisation for a brief period in the first decade of the twenty-first century, its reign is now over. It can no longer afford to have more generous and stringent social, environmental and public health rules. It is of course undeniable that the relative global market sizes of both the EU and the US are shrinking because of the rise of emerging economies. As a result, politicians across the Atlantic look at China as a key contender for global economic and political leadership. Whereas the shares of global imports of the US and the EU in 2002 amounted to 25.7 per cent and 18.9 per cent respectively (44.6 per cent in total), this had decreased a decade later to 16.2 per cent and 16 per cent (or 32.2 per cent on aggregate). Over the same period, China’s share of global imports almost doubled, from 6.3 per cent to 12.6 per cent (Eurostat 2015).

In such a context of rapidly declining economic leverage, the reasoning is that the US and the EU ‘need to maximize [their] influence by sticking together’ (De Gucht 2014a). This view is fully shared by the new EU Commissioner for Trade, the Swedish liberal Cecilia Malmström. In her confirmation hearing before the European Parliament, she noted that ‘there is a strategic dimension to the regulatory work [in TTIP]. If the world’s two biggest powers when it comes to trade manage to agree standards, these would be the basis for international cooperation to create global standards’ (cited in European Parliament 2014: 8). Similar statements have also been made on the American side. For example, US President Obama declared in his 2015 State of the Union address that, ‘as we speak, China wants to write the rules for the world’s fastest-growing region…. Why would we let that happen? We should write those rules’ (White House 2015; see also White House 2013b). The US’s acute concern with the rise of China, which has led (among other things) to its ‘pivot to Asia’, has meant that TPP and TTIP have explicitly been seen as a way of containing China economically. This is an even more aggressive version of the geo-economic rationale than that usually articulated by EU leaders.

To sum up, a central argument for advocates of TTIP has been the ability to set joint global standards in the face of the rise of China (and other emerging powers). This narrative is in line with the perception, especially persistent in the EU after the crisis, that European and American market power is declining. It has led to a remarkable redefinition of the relationship between the EU and the US when it comes to regulatory values and culture. In the first years of this millennium, there was a lot of emphasis on the unique ‘European model’ as distinct from more laissez-faire visions of capitalism in the US, especially with regard to the responsibility of the state, tax and social policies, and the role of the precautionary principle in environmental and health policies. This unique model had to be protected in the face of globalisation through a distinctive trade policy aimed at ‘managing globalisation’ (a term coined by then EU Trade Commissioner Pascal Lamy), often against the US view of more unfettered globalisation (Jacoby and Meunier 2010).

In the meantime, the emphasis on differences between the EU and the US has given way to stressing the fundamental similarities between values and policy models across the Atlantic to make transatlantic cooperation seem more natural. This shift from highlighting paradigmatic difference to fundamental similarity when it comes to EU and US regulatory values and models is not only a key discursive tool to counter criticisms of transatlantic regulatory convergence. It is also a necessary stepping-stone in the construction of the narrative that the EU and the US can agree on ‘setting global standards’.

However, we show in the remainder of this chapter that, even if (for the sake of argument) the EU and the US can succeed in overcoming regulatory differences, this will not automatically lead to the establishment of global standards. There are different ways to achieve regulatory alignment, and these have very different consequences.

Regulatory cooperation: the devil is in the mode

This is not the place to write an extensive history of the international trade regime or to explain in an elaborate manner when and why regulatory barriers came onto the agenda. We will address these issues at greater length in chapter 3. Suffice to draw the reader’s attention to what is known in the literature as the ‘reef theory’. An analogy is drawn here between traditional trade barriers such as tariffs and quotas (the ‘sea level’) and other, so-called NTBs or ‘behind-the-border barriers’ (the ‘reefs’). Reefs have become increasingly visible because obstacles to international trade – the sea level – have been lowered after successive rounds of multilateral trade agreements (under the GATT/WTO) have reduced tariffs to historical lows and abolished quota restrictions. In the 1970s, non-tariff barriers were still understood in a rather limited way as barriers to trade that were not tariffs but had a similar, explicit intention to restrict trade, such as countervailing or anti-dumping duties, voluntary export restraints or direct subsidies to enterprises. Increasingly, the term ‘non-tariff barrier’ has come to cover regulations whose primary objective is not to restrict trade but which serve other potentially legitimate policy goals, such as, for example, health, consumer or environmental protection. As we will discuss in the next chapter, non-tariff barriers have not simply been ‘discovered’ because of a natural lowering of the sea level. The concept was in large part also manufactured by a ‘redefinition of the common sense concept of “trade barrier”’ (Lang 2011: 224).

Differences in regulations that prescribe specific product or service requirements, or regulate the way a product or service is produced and/or delivered, have often been identified over the past decades as the most important remaining obstacles to international trade. This also applies to the transatlantic trade relationship. As the impact assessment preparing the ground for the TTIP negotiations states, ‘regulatory measures constitute the greatest obstacle to increased trade and investment between the EU and the US, identified in numerous studies and surveys and public consultations, as well as by way of anecdotal evidence’ (European Commission 2013a: 17).

How can states deal with these differences in regulations while trying to limit the negative effects this has on trade? One of the general trading rules of the WTO – this also applies to regulations – is known as ‘national treatment’; states are free to decide which regulations to apply, but they have to apply these in a non-discriminatory fashion to all providers, be they foreign or domestic. The WTO’s TBT and SPS agreements include a number of other, mostly procedural, prescriptions for adopting regulatory measures, but the EU and the US have clearly stated that their intention is to go much further in TTIP and ‘eliminate regulatory divergence’ to a significant extent. However, they have not yet specified clearly how this will be realised. Nonetheless, this is crucial for the geo-economic justification of TTIP.

If states want to go the extra mile with regard to regulatory cooperation, going beyond national treatment, they have two principal options (with some further distinctions we develop below): either a ‘harmonisation’ of their erstwhile different rules or simply a ‘mutual recognition’ of existing rules (which remain distinct). In the case of harmonisation (mode 1 in table 2.1), regulatory ‘diversity is overcome by finding a common denominator’ (Schmidt 2007: 261). If the EU and the US have different requirements, for instance, for headlights, bumpers or seat belts for cars (an example the European Commission is wont to use), they could decide, in future, simply to apply either the EU’s rules or those of the US or jointly to adopt an international standard – perhaps from UNECE (as has been suggested in the case of motor vehicles). However, as a close reading of position papers by the European Commission suggests, and as has been confirmed in a number of interviews we conducted with policymakers,2 the harmonisation approach cannot be expected to be adopted widely, if at all, in TTIP. On its Q&A webpage about the agreement, the Commission is very explicit about this: ‘harmonisation is not on the agenda’ (European Commission 2015f). The reason is that it is seen as (politically) very difficult and administratively cumbersome for negotiators to agree for each and every regulation which party’s rules may be superior and will be adopted by the other side, or to recognise that both have in the past been applying standards that are inferior to an already existing international regulation that will henceforth be applied. Moreover, the outcome of harmonisation towards one of the parties’ existing rule or standard is seen as zero-sum from a political economy perspective: only one of the parties has to suffer the complete adaptation cost, while the other has to bear none.

It is therefore more likely that the approach to be followed will be one of mutual recognition.3 This mode of regulatory cooperation can be defined as ‘creating conditions under which participating parties commit to the principle that if a product or service can be sold lawfully in one jurisdiction, it can be sold lawfully in any other participating jurisdiction’ (Nicolaïdis and Shaffer 2005: 264). Under this approach, the EU and the US would keep their diverging car safety standards for bumpers or seat belts, but they would formally recognise that these parts of their regulatory systems for motor vehicles are broadly the same in terms of their impact on safety. This mode has the practical advantage of avoiding having to have both parties agree about which standard is superior and of thus burdening one side with the adjustment costs. But, while mutual recognition might be preferable from a negotiator’s point of view, there are a number of problems that may arise from adopting such a mode of regulatory convergence.

The approaches to regulatory alignment we have discussed above differ fundamentally when it comes to their vision of, and hence the consequences for, the state–market relationship.4 With national treatment (the status quo), there is the primacy of (national) politics, insofar as governments have considerable freedom to set standards that will serve a public policy purpose. With mutual recognition, there is the primacy of the market, insofar as firms have the choice of which standard they choose to comply with. Finally, with harmonisation, political governance over the market is reinstated at the supranational level, with a new standard being determined as a result of a political negotiation. As a result, Joel Trachtman (2007: 783) argues that ‘[mutual] recognition is by its nature purely deregulatory’, insofar as it allows firms to bypass higher standards. He therefore notes that mutual recognition can be desirable only when underpinned by essential harmonisation, where a minimum standard is agreed, as within the EU’s Single Market. We discuss the implications for levels of risk protection and democratic decision-making of different approaches to regulatory cooperation more elaborately in chapter 3. In the remainder of this chapter, however, we turn to the question of how the choice of mode of regulatory cooperation affects the ability of the EU and the US jointly to ‘set global standards’.

We therefore have to make some further subtle but significant distinctions. Firstly, parties to regulatory cooperation agreements can decide not to go as far as really recognizing each other’s substantial standards and accept that their differences in actual standards are legitimate and reasonable. They may still agree, however, that it is unnecessarily costly for exporters to have their products tested doubly – not only in their home country but also in the country of destination. In that case, they could decide to let the differences in substantial standards exist but to mutually recognise each other’s conformity testing procedures and bodies (mode 4 in table 2.1).

Alternatively, they could go a step further and decide to mutually recognise each other’s substantial standards (as in the example given above for car safety). Again, this can be done in two different ways. The benefits of mutual recognition can be extended to the rest of the world, meaning that all exporters to the EU and the US would profit from having to comply with only one of the TTIP partners’ regulations to access both markets. This is what is called erga omnes mutual recognition (mode 2 in table 2.1) and is how the EU’s Single Market works – countering fears among third countries during the late 1980s that its completion (‘Europe 1992’) would result in a protectionist ‘Fortress Europe’ (see Hanson 1998).

Table 2.1 Modes of regulatory cooperation and TTIP

Note:*However, harmonisation does not guarantee a race-to-the-top dynamic. This would happen only if both parties were to agree to adopt the highest standard, be it an existing US, EU or international standard or a new, more ambitious standard.

In contrast, the benefits of mutual recognition could be limited to suppliers located in either party in what is known as bilateral mutual recognition (mode 3 in table 2.1). In this case, a car produced in the EU according to EU safety regulations could be marketed in the US without having to undergo adaptations to US standards. But this market access advantage would not be extended to suppliers from outside the EU (or from outside the US in the case of the EU market). It would imply a cost reduction for EU and US car manufacturers with sales on the other side of the Atlantic, but it would not grant the same advantage to third-country producers. Outsiders would even be at a competitive disadvantage, as they would have to keep producing different car models meeting different regulatory requirements, while their EU and US competitors would be exempted from that burden.

While the negotiators have not communicated in detail as to how they are pursuing regulatory cooperation for different sectors, based on what is written in position papers and interviews we have conducted,5 we argue that it is reasonable to expect that, for those sectors where substantial regulatory convergence is pursued, bilateral mutual recognition will be the chosen approach. The EU has stated its preference for that mode because it makes regulatory cooperation more attractive for those sectors that hope to gain from regulatory cooperation while limiting the costs for those sectors that stand to lose from real regulatory alignment. For the car sector, one of the largest beneficiaries of an ambitious comprehensive agreement according to the European Commission’s impact assessment, the Commission notes that ‘it can be reasonably assumed that in reality the outcome of negotiations on the NTMs [non-tariff measures] … would rather result in bilateral than in erga omnes recognition of safety standards; … [in that case] the positive effect on output in the car sector could even be bigger’, because only EU firms would get easier access to the US market but not others, and vice versa (European Commission 2013a: 43, emphasis added). The Commission arrives at the same conclusion for the electrical machinery sector, which stands to lose considerably from TTIP. Seeking to assuage fears, it states that ‘the expected approach to be followed in the negotiations with the US would focus on regulatory coherence and a degree of mutual recognition between the EU and the US standards’ without entailing ‘spillover effects to third countries’. Increased competition through improved market access would be limited to US firms and not apply to the rest of the world (ibid.: 41).

Analysing statements on how regulatory cooperation will be pursued in TTIP (a task that requires proficiency in ‘the art of reading footnotes’) reveals that mutual recognition is much likelier to result than harmonisation, and that this is to apply bilaterally rather than erga omnes. As we will see in chapter 3, this choice corresponds to the preference of multinational enterprises that are active on both sides of the Atlantic and risks unleashing a deregulatory dynamic. But, here, the crucial conclusion to draw is that bilateral mutual recognition does not provide added incentives for third-country firms to adopt EU/US standards, as doing so would offer no additional advantages vis-à-vis the status quo.

TTIP is unlikely to lead to global standards

The more (the economic rationale for) TTIP has been criticised over the past two years, the more its advocates have put forward a geo-economic and geopolitical rationale. This is often directed at more progressive critics, promising them the possibility of establishing high global standards while also invoking the gloomy prospect of having to conform to Chinese rule(s) if TTIP is not concluded. However, in this chapter we have shown that TTIP does not automatically translate into prolonged economic leadership for the EU and the US. What is more, the agreement may even accelerate the decline in regulatory leadership of both entities, and of the EU in particular.

The probability that TTIP will generate ‘transatlantic regulatory power’ depends on the modalities of the agreement and, more specifically, on the mode of regulatory cooperation. A harmonised standard – where one and the same standard is jointly agreed – stands the highest chance of being adopted by third countries and, thus, of becoming a true global rule. But the negotiators have indicated that this is not a feasible outcome of the negotiations in most areas. Erga omnes mutual recognition, which we have argued is also less likely to be used, could similarly provide an attractive incentive for third countries to align their regulations with those of the EU or the US, because this would immediately provide them access to the other party’s market.

However, if the EU and the US choose only to mutually recognise each other’s rules bilaterally, as we argue is most likely, this will not incentivise third countries to align their standards with transatlantic ones. It would mean that third countries’ enterprises will not enjoy the advantages of TTIP, and consequently they will have little or no reason to change their current practices (or to lobby their governments to align their regulations). On the contrary, they stand to be disadvantaged competitively vis-à-vis firms located on both sides of the Atlantic and might ultimately lose their presence on the transatlantic market. As a result, trade diversion may occur (for the impact of this on developing countries, see Rollo et al. 2013); suppliers from outside the transatlantic region would lose market share here to EU and US competitors and may therefore shift their exports elsewhere. This comes on top of the trade diversion resulting from bilateral tariff elimination. This may make it less, rather than more, likely that third countries would align their regulations with those of the EU and/or the US. The transatlantic partners would thus stand to lose instead of gain market power because of TTIP.

Mutual recognition may also impact negatively on global regulatory leadership in a second way, even if it were to be applied erga omnes. In cases where there are significant differences between current EU and US standards, third-country firms could simply conform to the least costly standard and enjoy free access to the other market. For the entity with the higher current level of protection, this would mean losing influence over third countries’ regulatory practices when compared to the current state of play, as it would feel the pressure of competition from all firms opting for the lower standard. Given that EU standards are generally (if not always; see chapter 3) more stringent, this would see the EU lose comparatively more leverage than the US.

Thirdly, TTIP may also undermine the EU’s soft power as the supposed distinctiveness of its economic and regulatory model, much applauded during the mid-2000s, is diluted (see Defraigne 2013). This would be not just the consequence of a TTIP deal with substantial regulatory convergence provisions but already follows from the broader discourse invoked by advocates of a transatlantic trade deal which emphasises shared EU and US values (and, more concretely, regulatory goals, systems and outcomes) and the threat posed by China as an emerging regulatory power.

It is a mistake to assume that TTIP will automatically lead to the ‘setting of global standards’ by the EU and the US, thereby containing the rise of China. However, the narrative that the transatlantic alliance should leave behind the quarrels of earlier days to avoid being relegated in the global order is useful to convince people that it is not transatlantic regulatory cooperation but its absence that is something to fear. This brings us to the key dimension and objective of TTIP, on which we focus in the following chapter: bridging regulatory differences and cutting red tape.