Human Habitat Should Nourish the Mind, Body, and Spirit

Asheville, North Carolina (photo by F. Kaid Benfield)

Although I have spent much of my career analyzing the tangible and measurable, I believe it critical that we not stop there. Indeed, our human habitat should address—or at least be supportive of—the more elusive parts of our overall welfare, providing nourishment to the body, mind, and spirit. Otherwise, what’s the point? Surely commerce alone isn’t enough. As it turns out, urban thinkers have had a lot to contribute on the subject.

Intriguingly, some urbanists have gone so far as to say that cities can and should be places of healing. The Healing Cities Institute, based in Vancouver, has adopted a “foundation statement” that explicitly connects human health and well-being with physical place:

“The healing process in the human body is the ability to rebuild, repair and regenerate cells, tissues and organs. Regeneration draws upon the body’s innate intelligence to heal itself.

“What would it then mean for a city to be ‘healed,’ and eventually to reciprocate and be healing and heal itself, its inhabitants and visitors? Furthermore, what methods and processes would support cities to facilitate healing in the context of sustainability planning? How might the built form and natural spaces of the city nurture and develop its residents’ holistic health—to include addressing physical, emotional, mental, social and spiritual needs?”

For those of us who deal in numbers, I’ll admit that this sort of language requires a generosity of spirit toward those who have an interest in more elusive concepts. But, the more I think about the true components of sustainability, the more I believe the subjective is every bit as important as the tangible.

The Healing Cities group’s statement continues:

“Key findings in the literature review reveal that healing involves much more than curing physical ailments. Healing is a multidimensional process facilitated by integrating physical, mental, spiritual, emotional, and social components of a person’s being. Each component affects the others. This awareness changes the relationship between people and their environments because it recognizes that people do not live as isolated islands, but rather are intimately connected to their surroundings and influenced profoundly by a range of factors.”

These concepts do get a bit more specific. Mark Holland, an urban planner and one of the founders of Healing Cities, wrote an excellent essay called “Eight Pillars of a Sustainable Community,” in which he articulated the following essential attributes:

- A complete community (covering land use, density, and site layout; integration of mixed uses and incomes; respect for natural areas)

- An environmentally friendly and community-oriented transportation system (covering walkability, transit, complete streets, and the like)

- Green buildings

- Multi-tasked open space (providing accommodation for both community and environmental needs, with community gardens—“Food should be celebrated in the landscape”—and active and passive recreation opportunities)

- Green infrastructure (covering stormwater management; water, waste, and solid waste management; energy and emissions; and “eco-industrial networking”)

- A healthy food system (covering food stores, restaurants, farmers’ markets, gardens, and festivals)

- Community facilities and programs

- Economic development (“encouraging the development of real job opportunities appropriate to the income level of the neighborhood, including live/work opportunities…”)

The wording of the Pillars evolved into a very similar but more general set of principles when adopted by the Institute. (Put another way, the Institute employed the language of human aspiration and avoided planning jargon.) For example, “healthy abundance” replaces “economic development”; “restorative architecture” replaces green buildings; “thriving landscapes” replaces open space. If the new language is more ambiguous than the original Pillars, it is also more inviting to non-planners.

Writing in the Vancouver Sun, Kim Davis reports that participants in a recent Healing Cities conference “acknowledged the ‘woo woo’ stigma that arises among critics at the mention of emotional and spiritual needs.” But her article notes also that the city of Vancouver had already begun moving in that direction by explicitly advocating “beauty” in the city’s planning policy.

New Orleans (photo by F. Kaid Benfield)

Davis spoke with my friend Hank Dittmar, chief executive of The Prince’s Foundation for Building Community, who made the case:

“We thought [talking about zero-carbon housing in a UK project] was a good start, but we thought it maybe ought to be healthy, natural and beautiful as well, so that people would actually want to live in these buildings.

“It is time to come out of the closet about our spirits.”

Holland’s Eight Pillars evoke not just the Seven Pillars of Wisdom of T.E. Lawrence and the biblical book of Proverbs, but also the work of another friend, architectural thought leader Steve Mouzon. (I mention Steve’s work in a number of these essays.) Steve has articulated a number of essential foundations for sustainable places (nourishable, accessible, serviceable, securable) and buildings (lovable, durable, flexible, frugal).

In a 2011 essay, Steve described “wellness lenses” of body, mind, and spirit through which one can consider the built environment. In each case Steve equates wellness with basic health, or absence of illness, if you will; but he argues that there is also a higher aspiration of “fitness,” to which places can also contribute.

Sustainable places can nourish wellness and fitness of body, he writes, with access to healthy food, opportunities for physical activity (“great places to bike, walk, and run”), and reducing the risk of automobile accidents. I would add, and I’m sure that Steve would agree, that clean air and water, and access to a range of health services, are critical components, too. These, too, can be influenced if not entirely controlled by how we conceive the built environment.

Steve believes that wellness and fitness of mind are fostered by the connections that come with true community, and by access to nature. The research certainly supports those points, and I would add that a little peace and quiet helps, too: we need places of reflection as well as of activity and stimulation. While nature—if present—often supplies the former, it does not always do so. I also think that mental health requires urban systems that work well, such as transportation options that relieve stress through comfort, efficiency, and reliability rather than creating it with noise, uncertainty, fear, and congestion. And perhaps above all, our communities and neighborhoods need good schools, without which wellness of mind becomes just about impossible for kids and their families.

Steve reaches some of those points, such as the need for places of reflection, under his discussion of wellness of spirit. He hits his stride in this section:

“Wellness of spirit increases when we love our neighbors... but the co-inhabitants of countless subdivisions aren’t really neighbors because the places are designed in such a way that people seldom meet and speak with each other. So how can we love our neighbors if we don’t have any?

“Wellness of spirit grows when we do good for others less fortunate. Unfortunately, the American development paradigm has become excruciatingly efficient at separating classes of people in a very fine-grained way so that it is now possible to go interminably through one’s daily life in many places in sprawl without ever seeing anyone notably less fortunate. So how are we going to do good for others less fortunate if we never see them?”

Steve continues by stressing the value of time:

“[T]he focus of our built environment in recent decades has been all about getting bigger and getting more. And we’ve mortgaged ourselves within an inch of our financial lives... or beyond, as many have sadly discovered. Which means that we have to spend countless hours working to pay for it all.

“So it all comes back to time: spending all our time working break-neck for [material] things assures that there’s no time left to build our spiritual wellness.”

That rings true, if also a bit depressing.

If the quality of our places—our habitat, if you will—can support wellness and fitness, does that mean it can also help us achieve happiness? Don’t scoff—it’s in our national DNA: the pursuit of happiness is the only basic human right mentioned not just once but twice in Thomas Jefferson’s powerfully written introduction to the Declaration of Independence.

Research on the subject finds that good, well-connected urbanism is a significant contributing factor to happiness. In particular, a fascinating study authored by a team from West Virginia University and the University of South Carolina Upstate, and published in 2011 in Urban Affairs Review, examined detailed polling data on happiness and city characteristics from international cities. In an article titled “Understanding the Pursuit of Happiness in Ten Major Cities,” the authors summarized their conclusions:

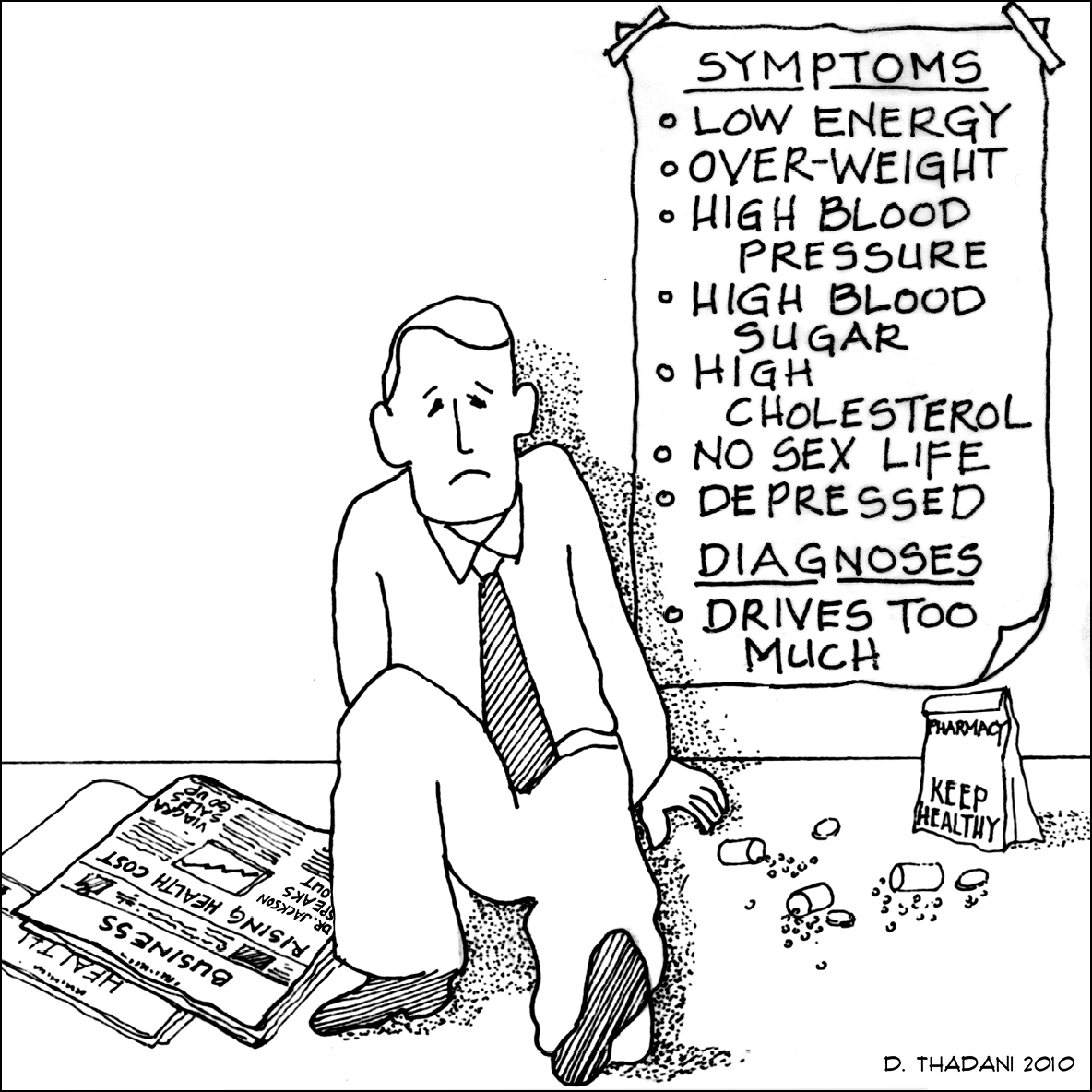

Modern man (drawing courtesy of Dhiru Thadani)

“We find that the design and conditions of cities are associated with the happiness of residents in 10 urban areas. Cities that provide easy access to convenient public transportation and to cultural and leisure amenities promote happiness. Cities that are affordable and serve as good places to raise children also have happier residents. We suggest that such places foster the types of social connections that can improve happiness and ultimately enhance the attractiveness of living in the city.”

(City characteristics are not alone in influencing happiness, of course. The researchers cite a “Big Seven” group of factors recognized by prior study as most substantially affecting adult happiness: wealth and income, especially as perceived in relation to that of others; family relationships; work; community and friends; health; personal freedom; and personal values.)

The researchers drew from an extensive quality of life survey undertaken by Gallup in 2007 for the government of South Korea and published in 2008. Approximately 1,000 people were surveyed from each of ten cities: New York, London, Paris, Stockholm, Toronto, Milan, Berlin, Seoul, Beijing, and Tokyo. Respondents self-reported their overall degree of happiness (measured on a scale of 1 to 5) along with their degree of agreement with a range of statements designed to tease out additional factors.

The team examined the findings, looking for statistically significant correlations. They found confirmation of the Big Seven factors, but also variations that could not be explained by the Big Seven.

In particular, the Gallup study examined a number of questions directly related to the built environment, including the convenience of public transportation, the ease of access to shops, the presence of parks and sports facilities, the ease of access to cultural and entertainment facilities, and the presence of libraries. All were found to correlate significantly with happiness, with convenient public transportation and easy access to cultural and leisure facilities showing the strongest correlation.

The statistical analysis also included questions related to urban environmental quality apart from cities’ built form, and produced additional significant correlations:

“The more respondents felt their city was beautiful (aesthetics), felt it was clean (aesthetics and safety), and felt safe walking at night (safety), the more likely they were to report being happy. Similarly, the more they felt that publicly provided water was safe, and their city was a good place to rear and care for children, the more likely they were to be happy.”

Among these, the perception of living in a beautiful city had the strongest correlation with happiness. Curiously, though, the researchers found that the perception of “clean streets, sidewalks, and public spaces” actually had a somewhat negative association with happiness. Happy people apparently find their urban environments both beautiful and messy. (Well, the survey did include New York.)

Arles, France (photo by F. Kaid Benfield)

Neighborhoods are particularly significant to connectedness and happiness, the team reports:

“City neighborhoods are an important environment that can facilitate social connections and connection with place itself…But not all neighborhoods are the same. Some are designed and built to foster or enable connections. Others are built to discourage them (e.g., a gated model) or devolve to become places that are antisocial because of crime or other negative behaviors. Increasingly, researchers and practitioners have become aware that some neighborhood designs appear better suited for social connectedness than others.”

It goes against the grain in today’s environmental world to be concerned with things other than tons of carbon dioxide, acres of land, inches of sea level rise, or dollars in a government budget, but for me a concentration only on the objective—or even only on the environmental—can lead to a world (not to mention a vocation) without soul and feeling. I believe we do ourselves and our heirs a disservice if we do not take a more holistic view in crafting our ambitions. If we don’t get places right for people, it won’t matter what they can do for the environment.

More about Well-Being

A Public Index of Happiness

The government of the Himalayan country of Bhutan regularly surveys its citizens on the state of nine key indicators of happiness:

- Psychological well-being

- Physical health

- Time or work-life balance

- Social vitality and connection

- Education

- Arts and culture

- Environment and nature

- Good government

- Material well-being

The use of a “gross national happiness” index has been a policy of Bhutan now for nearly four decades.

Elsewhere, the government of Victoria, British Columbia has participated in a Happiness Index Partnership comprising the Victoria Foundation, United Way, the University of Victoria, and several local and provincial government agencies. The partnership’s “well-being” survey has revealed the following:

“Most residents of Greater Victoria experience relatively high levels of well-being. These high levels of well-being are buoyed by strong social relations, feelings of connectedness to community, and relatively low levels of material deprivation for most members of the community. The primary factors that limit a greater sense of well-being across the population are time stresses and the challenges of living a more balanced life.

“There are, however, significant populations who experience lower levels of well-being—particularly low-income earners and single parents. These groups also face substantial time stresses but are less likely to enjoy the material and social supports that help to buttress the effects of the stress on their sense of well-being.”

While the overall findings were positive, only 26 percent of the Victoria respondents reported that they spent most or all of their time in a typical week doing things that they enjoyed, according to a summary report. About the same portion reported that “not much” of their time was spent on enjoyable activities. Only 31 percent described their lives as “not very” or “not at all” stressful.

Curiously, some scholars see the study of happiness as a branch of economics, or at least a critical examination of traditional macroeconomics. Among the academic works that discuss it in detail are Happiness: Lessons from a New Science, by noted British economist Lord Richard Layard; Economic Growth and Subjective Well-Being: Reassessing the Easterlin Paradox, by the University of Pennsylvania’s Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers; and The Pursuit of Happiness: Toward an Economy of Well-Being, by Carol Graham, at the time a senior fellow in global economy and development at the Brookings Institution.

(The Easterlin Paradox is named for American scholar Richard Easterlin, who found that, within a given country, people with higher incomes were more likely to report being happy. However, in international comparisons, the average reported level of happiness did not vary much with national income per person, at least for countries with income sufficient to meet basic needs. Subsequent researchers, including Stevenson and Wolfers, have found happiness linked to income for both individuals and for countries.)

Proving that even the most upbeat of subjects can be made deadly serious, Brookings has so equated happiness with economics that it chose April 15—“tax day” in the US—to host a forum on the subject in 2010.