But the Past Is Not the Future

Thanksgiving 1870 by Edw. Ridley & Sons Co., New York City (public domain)

While I believe strongly that paying attention to legacy in our built environment is important both to sustainability and to our self-awareness, we should not make the mistake of confusing legacy with demographics. The society of tomorrow—and the environment required to support it—will be fundamentally different from that of yesterday or even today. I began this essay on the day before Thanksgiving, as I was contemplating a gathering of extended family on this most familial of holidays.

We romanticize family in our society: just watch TV commercials for confirmation. But does our idealized version of family life resemble real family life? Does it exclude people who are not part of or close to their families? Is the concept of “family” changing, with implications for the built environment? The answers are, of course, seldom; usually; and definitely.

Why does this matter to communities and sustainability? Because we must plan the future of our cities and neighborhoods to account for reality, not our memories, or a rosy version of what some believe today’s households “should” be, or even our own personal situations.

As it turns out, the way households are going to be evolving over the next few decades is toward more singles, empty-nesters, and city-lovers, none of whom particularly want the big yards and long commutes they may have grown up with as kids. A significant market for those things will still exist, but it will be a smaller portion of overall housing demand than it used to be. This new reality means that the communities and businesses that take account of these emerging preferences for smaller homes and lots and more walkable neighborhoods will be the ones that are most successful.

The Great Convergence

My friend Laurie Volk, a market analyst of considerable wisdom and repute, says that a major underlying reason for these market shifts is the “great convergence,” as she calls it, of the two largest generations in American history. Together the Baby Boomers (born roughly 1946-1964) and Millennials (sometimes called Generation Y born roughly born 1981-2000), account for more than 150 million Americans, a little less than half of the total. Today, neither the city-oriented Millennials nor the empty-nesting Boomers fit into the traditional suburban housing market to nearly the same degree as the Boomers did a few decades ago, when they were raising kids and the kids hadn’t yet become the Millennials.

In the 1960s and 1970s, fully half of American households were couples with kids. That portion is already down to a third and headed to become only a quarter of the total.

Yet the current mixture of housing types on the ground—especially that built within the pre-recession time frame of from 1975 to 2005 or so—doesn’t come anywhere close to matching the more current preference for walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods. Wonder no more why city living is becoming more expensive.

Indeed, real estate analyst extraordinaire Arthur C. (Chris) Nelson was telling us as long ago as 2005 that, because of changing demographics and consumer preferences, the supply of large-lot suburban housing was already overbuilt in comparison to future demand. As a result, Nelson predicted that the value of large-lot properties was going to decline to less than their amount of mortgage debt, a circumstance now known as “under water.” Experience has proven his analysis to be right on target: although large-lot suburban homes weren’t the only ones that went into heavy debt and foreclosure during The Great Recession, there’s no doubt that they were hit the worst.

With one exception, inner locations lead the area’s housing recovery (image by F. Kaid Benfield via Google Earth)

I performed my own analysis of several data sets of real estate price changes in the metropolitan Washington, DC region over the past six years. There is a clear geographic pattern to the degree of change, with homes in the outer suburbs suffering the greatest percentage losses in value and the slowest rates of recovery. Median home sales prices in the inner city and adjacent close suburbs actually increased in some cases at the same time as those on the fringe were suffering losses of 25 percent or worse.

In fact, we now have examples where farmland that was sold for real estate speculation is now being sold again, back to farming investors who seek to return the land to crop production. If that doesn’t tell us enough about the shifts in the market for exurban housing, then consider the relative demise of the McMansion era of neo-trophy houses, their popularity now only a small fraction of what it once was.

There may be another market shift afoot, too: from a housing market dominated by owner-occupied properties to one with a higher share of rentals. Ben Brown of the small but highly respected planning and development advisory group Placemakers fears that in some ways our neighborhoods aren’t ready for more rentals:

“The problem is, outside of big city downtowns, where demand for rentals has always been high, the design and construction of apartments, town houses and other rental models hasn’t consistently measured up to the range and standards of single-family, for sale residences. In too many places, ‘for rent’ and ‘affordable’ have become code words for subsidized government housing or cheaply built complexes likely to be opposed by neighbors worried about their property values or the increased traffic congestion. There’s a stigma to overcome…

“The ideal approach would be to produce neighborhood-appropriate rental choices that are impossible to tell from for-sale dwellings. Historic in-town neighborhoods provide the best models. True townhouses. Appropriately scaled stacked flats. And, of course, single-family detached homes that toggle between owner-occupied and rented depending upon market conditions and owner preferences.”

If the market for rentals does indeed strengthen, perhaps the quality will pick up as Brown suggests it should.

More generally, since market forces usually do respond to changes in demand, we can probably expect to continue to see more urban and walkable suburban housing types built on currently vacant and underutilized properties. The question is how quickly the change will occur.

What the Census Says about the Modern American Household

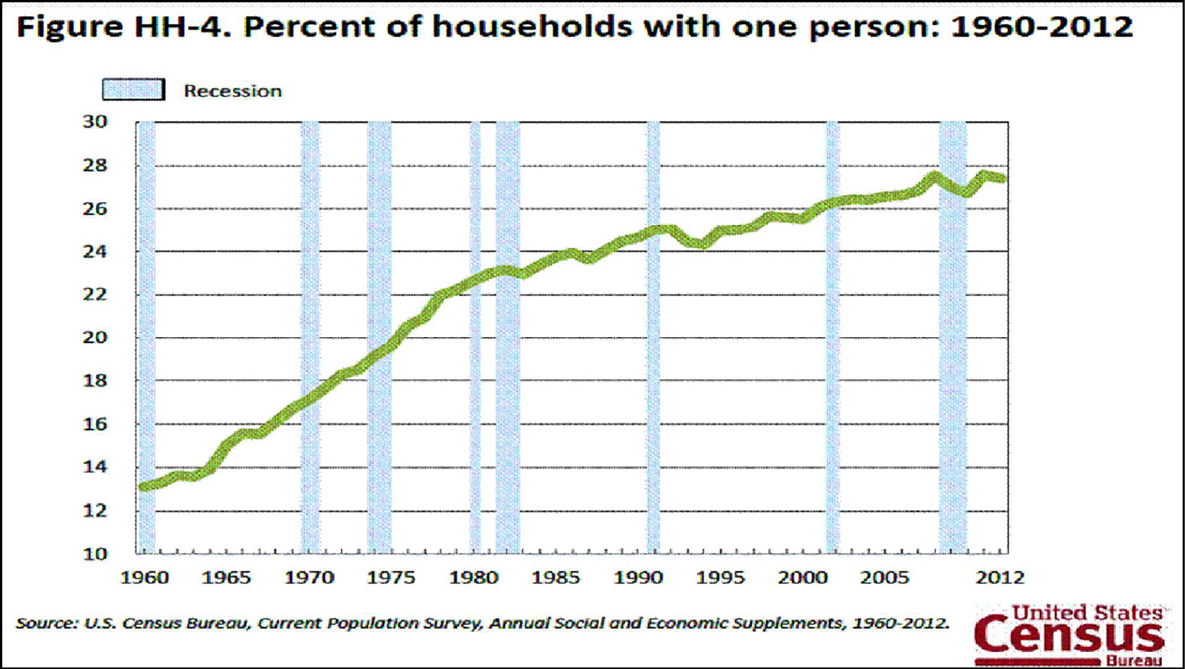

In 2012 the Census Bureau released some fascinating statistics about the state of American households. People are marrying later than they used to, for example, if they marry at all. This is one of the reasons why the number and portion of people living alone has risen steadily and significantly for decades.

The portion of children living with two parents has dropped dramatically from 1960, from just under 90 percent of all children in 1960 to around 70 percent in 2012. Statistically, almost all of the change can be explained by a dramatic increase in the portion of children living with single moms. (But it’s not for the old reasons: the percentage of kids living with widowed, separated, and divorced mothers has actually gone down in recent decades. There has been a sharp increase, however, in the portion living with never-married mothers.)

In general, married-couple households have declined sharply since the 1950s, from over 75 percent of all households then to about 50 percent now. The major share of that change has been an increase in “nonfamily households” consisting of singles or persons not “related to each other by birth, marriage or adoption.” Average household size has gone down, too, from about 3.7 persons in 1940 to about 2.6 persons now; family households have dropped from about 3.8 persons to about 3.1. (It says much about our consumptive society that, until very recently, the size of the average new home in America has been increasing dramatically even while household size has been declining.)

For a slim majority (52 percent) of married couples, both spouses are in the labor force. But the portion fitting the 1950s “traditional” model where the husband works and the wife doesn’t is much smaller (about 23 percent). In the remainder of married households, either the wife works and the husband doesn’t, or neither works. There has been a steady decrease in the portion of households where only the husband works since at least the 1980s.

Growth in one-person households (image by US Census Bureau)

Even for couples with kids under six years old, a majority of households have both spouses in the labor force. But, for married couples with kids under 15, about a quarter have stay-at-home mothers, consistent with the related statistic above.

What I take from all these data is that there really is no “typical” American family living under the same roof these days, if there ever was. Rather, we have a diverse and changing array of household types and circumstances that smart planners, builders, and businesses will seek to accommodate. The census data show that the growing parts of the housing market are nonfamily households, smaller households including people living alone, unmarried couples, single-parent households with kids, and older households. The declining parts of the market are larger families, married couples, two-parent households, and couples with only one breadwinner, though each of these categories clings to a significant share of the total.

In other words, just as Volk’s analysis of “the great convergence” of generations and Nelson’s analysis of current supply and demand trends suggest, the portion of households that is decreasing the most is exactly that portion most likely to seek homes in large-lot, outer suburbs. Look for continued lower prices in that market and continued high prices in the urban and walkable suburban markets until supply catches up to demand.

Looking to the Future

Forecasters inside the real estate industry agree. A report on the future of housing from The Demand Institute, a think tank that tracks consumer demand, also came out in 2012. Among the findings that are promising for more sustainable development patterns is the assertion that the strongest segment of today’s housing market “comprises populous urban or semi-urban communities well served by local amenities.” In the report, The Shifting Nature of US Housing Demand, the authors call this segment the “resilient walkables” and forecast a home price rise of up to five percent per year in this segment between 2014 and 2017.

The analysis confirms that the weakest segment of the market, by contrast, is located in outer and smaller suburbs or outlying areas that “are sparsely populated, and have low walkability.” Though prices for this segment are “relatively cheap,” the authors contend that the value of these “weighed down” properties will not increase enough to reach the national average even by 2017.

In other words, if you’re a real estate investor, put your money on smart growth and avoid sprawl. A closer read of the new report, however, contains a lot of nuances, mostly but not entirely consistent with what other analysts such as Volk and Nelson have been saying with regard to growing demand for walkable neighborhoods. From the report:

- Nationally, the housing recovery will accelerate between 2015 and 2017.

- The recovery will be led by increasing demand for rental homes, especially from younger people and immigrants. The national share of occupied rental homes as a portion of the total rose from 31 percent in 2005 to 35 percent in 2012, and home ownership has declined sharply among persons under 35. “The only segment of the home building sector now showing clear signs of recovery is multifamily housing,” driven by developers seeking to rent.

- But the dominance in rentals may be temporary. Conversion of for-sale homes now in oversupply to rentals will clear the excess, the authors say, after which home ownership will rise and return to historical levels.

- After increasing steadily for decades, the average size of the American home has begun to shrink and will continue to do so. By 2015, average new home size should be back to where it was in the mid-1990s.

- The extent to which walkability helps the market may depend on where you are. In addition to the strong “resilient walkable” category and the weak “weighed down” category, the report identifies two other segments: “slow but steady” homes in areas with average walkability and employment rates; and a “damaged but hopeful” segment, where neighborhoods are highly walkable but suffer from a weak regional economy. Both will see price recovery, though not as quickly and strongly as the resilient walkables; the slow but steady group will see it sooner than the damaged but hopeful group.

- In a prediction I find troubling, the report says that “neighborhoods will be increasingly segregated economically, resulting in polarization.” The authors observe that the portion of Americans living in middle-income neighborhoods has declined considerably in recent decades, while the portions living in both affluent and poor neighborhoods has increased. “Housing stock within neighborhoods will become more homogeneous.”

- While the increased demand for urban and walkable, transit-served neighborhoods is clear—the authors note the positive correlation between prices and walkability, as measured by the popular website Walk Score—“many Americans, particularly those planning to purchase, will move even farther from the city to suburbs where housing is more affordable.” (The report does not delve into the effect that energy prices may have on that movement.)

- Increased demand for urban, smaller, and rental properties will produce ancillary effects. Industries that will do well include home remodeling, carsharing, and portable appliances. Homes with less space for storage but more accessibility to shops may also lead consumers to more frequent purchases of smaller sizes of packaged goods.

So, particularly for those of us who seek a future of more mixed-income neighborhoods with a variety of housing types, we should pay attention to policy shifts that can help us get there, since this forecast suggests that the market alone may be helpful but not sufficient to accomplish the goal. The report also suggests that maintaining a supply of affordable for-sale units in high-demand walkable neighborhoods may be critical to dampening a potential rebound market for sprawl.

Still, after decades of both policy and market forces wreaking damage on central cities while paving over cornfields and forests to build mediocre development, the central finding is heartening:

“Although demand for new and existing homes will rise, consumer demographics as well as altered preferences will change the nature of that demand…demand will be high in areas well served with amenities that are within walking distance and that have a sense of community. Sprawling, featureless suburbs will be less attractive.”

The more cities and inner suburbs strengthen, the more the environment will benefit.

More about the Future

What Will Technology and Changes in Workplace Practices Mean for Cities?

I attended a meeting in Washington at which a prominent smart growth leader was showing a presentation on “the business case for smart growth.” Much of it was based on the need for everyday, face-to-face business communication within companies and the need for dense environments to facilitate efficient productivity and movement of goods. He stressed that this has always been the case, making connections to history and to studies reaching back for decades.

There was only one problem. Several meeting attendees were participating via conference call, following along via their computers and internet connections in remote locations. They were virtually countering the speaker’s point as he was making it.

Indeed, a number of participants in the meeting were environmental and urbanist organizations who were, and are, advocating telecommuting as a way of saving transportation energy and infrastructure. Transportation for America, a coalition with a staff based in Washington, DC, has a communications director who works remotely from Seattle. A prominent staff member at DC-based Smart Growth America works from Montana. An official at the US Patent and Trademark Office, which has an aggressive telecommuting program, reports that up to a staggering 80 percent of agency employees might be working from remote locations at any given moment. Heck, I have one colleague who worked seamlessly for NRDC (in theory, as an employee of our San Francisco office) from Italy for five years, for no other reason than because she wanted to and could make it work. And so on.

The modern workplace (photo courtesy of rxb/Richard)

Our speaker was making a twentieth-century argument in a twenty-first-century economy.

And yet the twenty-first century is shaping up as a decidedly urban epoch, with downtowns more popular than they have been in 50 years and suburbs reshaping themselves in ever-more urban forms. What’s going on?

Thomas Fisher, dean of the College of Design at the University of Minnesota, believes that we are undergoing an enormous change in “how people will live and work, in how businesses will operate, and in what services and support we will need from government.” Writing in The Huffington Post, Fisher contends that the 20th-century model of large-scale, heavy industry is largely over and that the new workforce is much more independent and nimble:

“In the next economy, ‘manufacturing’ may more-often occur at a micro scale, with free-lancers 3D printing in their back bedroom or the self-employed laser-cutting products in their garage…Self-employed entrepreneurs rely upon durable, high-bandwidth infrastructure in order to communicate with and ship to customers globally. They need affordable health care equivalent to what large companies provide their employees. And they tend to congregate in places with a high quality of life, where other entrepreneurs go.”

So, yes, we still want to congregate, maybe more than we have in a long time, but for different reasons now.

Continuing, Fisher explains that the new economy demands changes in our built environment, to encourage the use of old buildings in new ways and to foster intermingled homes, workplaces, and shops:

“With the rise of the contingent workforce, people will also live and work in ways we haven’t seen for a very long time. We have developed our cities based on the old economy, with residential, commercial, and industrial areas kept separate and ‘pure’ through single-use zoning. That made sense in an economy that divided our work lives from our private lives, and that spawned large-scale noxious industries that no one wanted nearby. The next economy, though, may look more like the way in which people lived and worked prior to the industrial revolution, in which home, office, and shop co-exist in some combination of physical and digital space. This may require rethinking our zoning laws to allow for a much finer-grain mix of uses and repurposing buildings designed for single functions that will have no tenants or buyers if they remain that way.”

With former retail mainstays such as bookstores and music stores giving way to digital commerce—and workplaces getting smaller—we’ll still need urban neighborhoods, mainly for “what we can’t get any other way.” This will certainly include face-to-face conversation, not necessarily for traditional business reasons but for socializing and for impromptu idea generation among entrepreneurs. And we may need a new educational approach, too—one that stresses creativity, since preparing students for an ordered world that is becoming less so every day could be a disservice.

These new realities, of course, lead directly to urban thinker Richard Florida’s argument that we need cities more than ever, not to maximize efficiencies in the old order but to nourish the creativity required for success in the new. He elaborates in Business Insider:

“Cities are veritable magnetrons for creativity. Great thinkers, artists, and entrepreneurs—the Creative Class writ large—have always clustered and concentrated in cities. Deeper in our past the concentration of people in cities not only powered advances in agriculture, but led to the basic innovations in tool-making and the rudimentary arts that came to define civilization…

“Real cities have real neighborhoods. They are filled with the flexible old buildings that are ideal for incubating new ideas. They are made up of mixed use, pedestrian scale neighborhoods that literally push people out into the street, cafes and other third places, encouraging the serendipitous interactions, the constant combinations and recombinations that result in new ideas, new businesses and new industries.”

So, in the end, the speaker who was making the “business case for smart growth” was right that modern businesspeople need urban environments, but perhaps not for the traditional reasons he was citing. If the reasons matter—and Fisher and Florida certainly suggest that they do—both city planners and companies should take note to ensure that they are prepared for new ways of living and conducting business. Cities will still be cities, but education, retail, and workplaces may all need to change, along with government services and regulation. The companies and communities that figure this out first are likely to be the ones that succeed best in the next economy. Likewise for urban advocates.