REFLECTIONS ON MOVEMENT DYNAMICS

Alan Hirsch, founding director of the Forge Mission Training Network and founder of 100Movementss

Tim Keller is one of the truly outstanding missionary statesmen in our time, a man who has not only significantly contributed to the renewal of the church but has actually managed to lead a church (in New York, no less) that has evolved under his leadership to be a burgeoning worldwide church planting movement. By his own admission, the key to his ministry is the drive to recalibrate God’s people around the centrality of the gospel and then to form a movement organized to deliver it.

I heartily agree. Throughout my own ministry and writing, I have tried to penetrate deeply into the dynamic phenomenon of missional (apostolic) movements.1 I have come to believe that the future viability of Christianity in Western contexts is bound up with rediscovering the world-transforming power of apostolic movements as a way of being church. The fate of each and every church is affected by this — one way or another.

Movements “R” Us

Perhaps the first thing that ought to be said is that movement is essentially a mind-set, a paradigm, rather than an alternative model. As such, movement thinking involves a distinct way of understanding what the New Testament calls ekklēsia— and what we call church. This way of thinking more closely reflects the original mind-set of the early church precisely because they were a movement. All New Testament ecclesiology is inherently movemental.

Yet throughout the ages, Christians have read the Bible somewhat anachronistically in this regard, reading later, more formal, institutional ecclesiologies back into the New Testament. We all read the Bible with a particular lens, and in this case, the lens that blurs our vision is the formal structure of church that followed the emergence of Christendom. But apostolic movements, as we see them unfolding in the New Testament church, tend to run contrary to the prevailing ways we think about church and mission. Most apostolic movements today have either an explicit or implicit critique of the church organizations from which they have emerged (or are expelled from). I mention this because we should never underestimate how deeply this institutional mind-set is embedded in our churches and how it unconsciously dominates most thinking about the church. If you were to ask non-Christians today about church, many would likely say the church is primarily a religion run in a building organized by a professional guild called the clergy.

New movements typically identify how the institution is deficient in some way, and they highlight new ways of being church that need to be developed to further the spread of the gospel message. These movements emerge from those parts of the church that are on the edge — those that are most committed to getting the message out in a meaningful way. Because of this, movements tend to be creative, energetic, generative, and adventurous manifestations of the kingdom of God. They are things to be celebrated and cultivated, as Keller advises, because they bring a much-needed answer to the pressing questions that face the church. In addition, they are often the catalyst for the church to extend its intended impact to reach the culture.

“It’s the Things People Know That Ain’t So”

In his book Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Robert Pirsig writes, “If a factory is torn down but the rationality which produced it is left standing, then that rationality will simply produce another factory. If a revolution destroys a systematic government, but the systematic patterns of thought that produced that government are left intact, then those patterns will repeat themselves . . . There’s so much talk about the system. And so little understanding.”2

In the West, where the landscape is dominated by institutional, existing churches, a paradigm shift is needed. Unless we can undergo a mind-set conversion, it is unlikely that the movements we develop will survive. Paradigms are painfully irritating things to see, but once we do get them, they are just about impossible to “unsee.” To truly extend the logic and impact of the New Testament message (the gospel), we will need to see the New Testament church in its original design as the primary means of delivering the gospel. In other words, to become a movement, we need to first think like a movement.

How do we precipitate this paradigm change? Here are several suggestions:

1. Feel the challenge/call at the heart level. All of this must begin in the heart. Leaders must work to cultivate holy discontent, creating a sense of urgency by defining the problem and calling people to live into the answer. In doing this, a leader will activate the latent potential that is embedded into the church. Movement, or the possibility of movement, is latent in all of God’s people because that’s how God has made us! We need to awaken our ancient-future imagination and use it.

2. Change the metaphor, change the game. We must move from the metaphors that are oriented around stability and control to ones that correspond to a more fluid understanding of the church (e.g., body, living temple, pilgrims, seeds, trees, and the like). Along with movement leader Dave Ferguson, we suggest:

The reason why metaphors are powerful descriptors is that they filter and define reality in a simple fashion (for example, “Richard is a lion,” “the brain is a computer,” or “organizations are machines”). Even simple words like amoeba, beehive, fort, and cookie cutter provide clues as to how people see and experience paradigms in relationship to organizations. For instance, if I said that such-and-such church was an elephant, what images come to mind? What if I had used the term starfish? Each metaphor will convey different information about reproductive capacities, mobility, strength, wisdom, personality, courage, and so on. Identifying the metaphors thus offers significant clues about where to focus the efforts at shifting the paradigm.3

Let me use a metaphor to make this point. Deb and I live in the city of Los Angeles. We have been there for seven years now and have lived in three different neighborhoods. For much of that time, LA did not make sense to me as a city or a community. You never seem to arrive in LA. The city has a population of approximately seventeen million people, yet it has no real center or any clear boundaries, for that matter. There is no unifying aesthetic, and each region disowns the other one, vying to be “the real LA.” Almost no one thinks that downtown is actually LA, except perhaps the downtowners themselves.

While I was puzzling over this last year, it dawned on me that I was using the wrong metaphor to understand this community. I was trying to see LA as a city, but to be honest, it does not make sense as a city. Instead I began to see LA as a country (with forty-five different cities). Suddenly I “saw” LA. I understood LA when I recognized it as a small country. After all, it has the same population as my native Australia. What a difference this small shift makes in how I think about my city.

Now apply this to the church. When I tell you that the church is an “institution,” how does that affect your thinking and understanding about the church? And how does it differ from what you see when I tell you that the church is a “missional movement”? The metaphors we use affect the way we think and what we experience. Change the metaphor, and you change the way you see and experience church.

3. Tell a different story. Austrian philosopher Ivan Illich is credited with saying, “Neither revolution nor reformation can ultimately change a society, rather you must tell a new powerful tale, one so persuasive that it sweeps away the old myths and becomes the preferred story, one so inclusive that it gathers all the bits of our past and our present into a coherent whole, one that even shines some light into the future so that we can take the next step . . . If you want to change a society, then you have to tell an alternative story.”4

I am convinced he is right. People and societies have always understood themselves by constructing stories that explain why things are the way they are. These defining stories (or controlling narratives) tell us who we are and how we got here. They offer an account of what’s been going on before we came on the scene. A story addresses the significant questions of life: Who am I? Where am I going? Who is going with me? Like every story, these narratives carry information about the defining incident, the conflict that exists, the challenges we must face, or the problems the organization (or individual) must overcome. The precipitating cause provides the theme around which the entire story unfolds.

Consider the stories the Nazis used when they came to power — how they made sense of the German story. Or what about the story told by Steve Jobs, the driving story behind everything he did to design and create Apple? What about the toxic narrative that jihadists tell themselves to justify the things they do? For good or ill, stories help us orient ourselves in our current situation and provide meaning for our actions — for good or for bad.

Consider the story we read in the Gospels. How does that story shape us? Listen to the tale Luke relates in Acts. We are in this story; we are chapter 29 of the book of Acts. Through a personal encounter with Jesus, we are now invited to leave our old lives behind and enter into Jesus’ story (see 2 Cor 5:17).

If you change the underlying story about the church, you begin to change the church. Are we, as a community, defined by the story Jesus tells us about the “good life” (to live for the King, to love others, to serve)? Or are we held together by the prevailing cultural scripts that tell us what constitutes “the good life” (education, wealth, suburban living, consumption, and the like)? What about the national narratives that define our sense of racial and ethnic identities (African American, Anglo-Saxon, Jew, and so forth)? These stories will inevitably define us if we are not shaped by the story of God. The story of the church is the narrative of the unfolding kingdom of God and includes God’s call to us to live in covenant relationship with him through Jesus our Lord. How well we know and embrace this story fundamentally influences how we see the church and understand its function. So consider: What is the story that holds your church together?

4. Experience liminality. Liminality is a sense of anomaly, marginality, and disorientation — even danger. Experiencing liminality is necessary if we wish to develop a sense of urgency and change the story. From liminality, we find the creative imagination to discover the new metaphors we need to sustain the church in its mission. As Keller reminds us, certain conditions of liminality are necessary to help us recover a more vigorous expression of the church.5

Another way to say this is that movements are felt as much as they are understood. They have a certain atmosphere. They exude a culture, and people sense the resulting “vibe.” These vibes cannot be objectively passed along and studied. They must be caught and experienced, and we “catch the vision” by allowing ourselves to participate in the unfolding story of the church as a transformative gospel movement. For Tim Keller and the folks at Redeemer, the liminal challenge is to be a gospel-centered church existing in the space of New York City. For you and your church, it may mean simply crossing the street to engage with your neighbors.

We change paradigms by creating urgency in conditions of liminality. These lead to the generation of new and dynamic metaphors. We change the language, tell a new story, and begin to transform the guiding template that lies at the core of the organization. If we fail to do this, our efforts at transitioning to a movement will be short-lived.

None of this comes easily, of course, but you can do it. Social psychologists tell us there are four stages in progressing from incompetence to competence in any major learning:

1. Unconscious incompetence. People in this stage are simply not aware of the issue at hand; they are incompetent, and they don’t even know it. At this stage, the leader’s task is to raise awareness so the learning process can begin. At the very least, this involves selling the problem before suggesting possible solutions and ways forward. Why? Because we know that the vast majority of people have to first experience some level of frustration in their actions or a significant disruption in their lives (individually or corporately) before they will change. At this stage, holy discontent accompanied by an imaginative search for answers will move people toward the changes necessary to get them participating fully in God’s mission. If you’ve picked up this book, chances are you’ve moved beyond this stage.

2. Conscious incompetence. Here the learner becomes aware of the issue and begins to “see it,” but at the same time they become aware of their own relative incompetence in adequately “doing it.” So the learner has to decisively push beyond the pressure from their prevailing understandings (which feel very comfortable and natural) and learn to live with significant discomfort and anomaly. This stage involves significant amounts of unlearning— even repentance, where necessary — in order to move on. Clearly, practicing the new ideas will feel unnatural at this point. It is critical not to simply retreat to what we know. Courage, vision, and determination are important.

3. Conscious competence. This phase happens when people understand the basic dynamics of the new paradigm but still need to concentrate in order to operate well; it is not yet second nature or automatic. Like a new driver, navigating the road takes concentration and practice, but the natural reflexes will come. The slogan “Practice makes perfect” may well apply here, until the final phase eventually comes.

4. Unconscious competence. Here the paradigm becomes instinctual; it is hard to see reality any other way. Those at this stage are true insiders of the paradigm and are now competent to teach others about what they themselves have learned and integrated.

The lesson here is this: To become “movemental,” leaders must make a choice and then stick at it. None of what you do will feel “natural” at first. Yet eventually, that will change. As the paradigm shifts and the culture changes, you’ll begin to “feel” this is the way it has always been.

Do you remember learning to drive a manual transmission car? How awkward it was at first, then how natural it felt? Or think about playing tennis (or developing any skill, for that matter). I suspect that the millennial generation and those who follow may better understand this way of thinking than preceding generations because they are familiar with the more fluid, adaptive, polycentric, amorphous, networked, meme-driven world that exists in the twenty-first century. For older leaders, welcome the contributions of these younger leaders and take them seriously.

Missional Ministry for Missional Movement

Movements are made up of people — lots of people. And these people find their place in knowing what the movement stands for. They are the real “believers,” willing to sacrifice much to see the movement deliver its message.

To Organize or Not to Organize — That Is the Question

All we have discussed inevitably raises questions about how to best organize, about stability, adaptability, and leadership. I believe that Keller’s emphasis on developing “institutions” that will help a movement last beyond the initial phases is vital here. I prefer to use the word structure rather than institution because I believe structures are always defined by and are subservient to the mission, and not the other way around. Institutions, as Keller points out, have a way of attaining a life of their own. This is especially true in churches where inherited traditions can gain a significance they were never intended to have.

The forms of the church ought to remain inherently adaptive. When we institutionalize a form, it easily becomes sacramentalized, placed beyond the pale of human critique. Church organizations, in particular, are notoriously hard to change because they put a Bible verse behind everything they do. This can be theologically and missionally disastrous because people tend to grow attached to the forms, even after they have become obsolete. They hold on to things that once worked but no longer do, to things that were once productive and no longer are.6 Again, this is a particular danger for religious or faith-based organizations when biblical authority is (con)fused with the institutional structure.

The truth is that all living systems, whether your body or the local church, need a structure and some form of organization. Ekklēsia (re)conceived as movement is not devoid of structure or organization. It’s just that the organization will tend to be different from what we have grown accustomed to seeing.7 The general rule in movements is that we structure just as much as is necessary to adequately empower and train every agent/agency in the movement so it can do its job. We seek to decentralize power and function as far as possible, pushing it outward to accomplish the mission. We teach direct accountability to Jesus and his cause and loosen up on control. If people are properly empowered and are living as responsible disciples of Jesus, they need more permission and less regulation if they are to do what Jesus wants to do through them.

In addition, we should seek to develop a deeper unity in Jesus and his cause — a unity that exists in dynamic tension with real diversity. The challenge here is to marry a solid core with a changing/adaptive periphery — what Dee Hock calls chaordic structure.8 Keller gives evidence throughout his chapters on movement dynamics that he realizes movements may be scary, as well as a little messier than what we are used to. Here I very much affirm Keller’s suggestion that we emphasize the movemental aspects of the organization to keep the organization moving forward. We must resist the tendency, innate to every organization, to slow down and lose momentum.

Leadership and Ministry Issues

All of this leads to questions about the structure of leadership in the church. Here is where I am admittedly more radical than Keller in my suggestions. Let me start by saying I believe the traditionally conceived forms of ministry cannot move us beyond the current impasse because they have led to the structures that currently exist — and they continue to sustain them. Albert Einstein’s dictum is correct as we apply it to the church: We cannot solve the problems of the church by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created those problems in the first place. In other words, we must thoroughly reconceive how we understand and practice ministry and leadership if we wish to truly be a movement.

Tim Keller understands this. He recognizes that the prevailing understanding of the orders of ministry (those we call the pastor and teacher) is insufficient for producing the kind of movement that is needed. Keller suggests we adopt a tripartite view of ministry instead (prophet, priest, and king; see pp. 203 – 6). While this is a definite advance over the limitations of the pastor-teacher model, I would point out that this is a later deduction drawn from the ministry of Jesus. It feels somewhat forced when applied directly to the ministry of believers.

I suggest an alternative, one that is explicit in Scripture and provides the typology of ministry that is needed to initiate, develop, and sustain movements — the Ephesians 4:1 – 16 model for leadership, commonly referred to by the acronym APEST (apostle, prophet, evangelist, shepherd, teacher).

The purpose of my reflections does not allow me to present a full argument for this model, but I mention it now because I believe it is vital if we hope to activate movemental forms of church today. I would start by referring readers to the text in Ephesians, to read it and set aside the prevailing Christendom scripts we’ve inherited about this passage. We must deliberately try to read what is being said here through the lens of movemental ministry. If we do this, I believe we will begin to see ministry in a whole new light.9

The first thing to bear in mind is that Paul — undoubtedly the outstanding practitioner of apostolic ministry in the New Testament — is giving us his best thinking about the nature and function of the church. Right here, at the heart of his letter (Eph 4), is his delineation of the essential ministry of the church. It’s written with a “constitutional” weight. Paul presents us with the logic of the church’s ministry.

• In verses 1 – 6, Paul calls us to realize our fundamental unity in the one God.

• In verses 7 – 11, he says that APEST has been given (aorist indicative=constitutional) to the church.

• In verses 12 – 16, he goes on to say why APEST is given. The answer? So that we might be built up, reach unity, become mature, and so forth.

He could not be clearer in what he says here. We cannot be the kind of mature, fully functional church envisioned in verses 12 – 16 without APEST, without the full ministry model that includes apostles, prophets, evangelists, shepherds, and teachers. The traditional Christendom argument does significant violence to the logic and grammar of the text. The phrase “has been given” in verse 7 relates to all APEST ministries. How, then, do we end up with our current ministry model of shepherd-teachers and ignore the rest? Why should we expect the outcomes promised in verses 12 – 16 if we are only operating with two-fifths of the full ministry of the church?

We need to recognize the full movemental power in having all APEST ministries. Let me give you a brief functional definition of each:

• Apostolic is the quintessentially missional (apostellō = sent = missio) ministry. As the name implies, the movement is outward toward the fringes. It involves the healthy extension of Christianity onto new ground. The apostolic person tends to be an innovator, a designer, a builder — someone who will likely have cross-cultural or intra-cultural impact. Important for any movement, the apostolic ensures the integrity and health of the movement across geography and time.

• Prophetic ministry involves a strong God-orientation. Prophets are essentially the guardians of the covenant relationship between God and his people. They feel what God feels and speak on his behalf. They call the church to faithfulness, obedience, and at times practice a necessary iconoclasm.

• Evangelistic ministry is the ministry of good news. He or she is an infectious person, the sharer of the gospel message. Essentially they recruit to the organizational cause. Because they reach outside the walls of the church, a grasp of cultural relevance is important.

• Shepherding ministry is the ministry of care — of healing, reconciliation, discipleship, wholeness, and community. With high EQ (emotional intelligence) and empathy, these people create the necessary social glue for movements to hold together over the long term.

• Teaching connects the dots that others cannot easily see. The teacher essentially transfers ideas meaningfully. They foster understanding in depth and impart wisdom for godly life. They guard the worldview and the content of the faith. They are the philosophers who create the intellectual trust of the church.

With these descriptions in mind, let’s look at the inherent balance in the system given in Ephesians. APEST has two sides that are necessary for movement. There is the more generative, non – status quo, ministry of the APEs. And on the other side we find the more operative ministries of the STs. The truth is that both of these dimensions are needed. The APE is by nature generative of new forms, more inherently movement oriented. The ST develops sustainability for the movement, akin to a human resources department. Why shouldn’t we have them all? And even more important, how can we expect to be a transformative movement if we only have a limited understanding of our mission and ministry? The lack of a full APEST ministry model has led to a serious reduction in our understanding of leadership and ministry and has damaged our ability to mature.

Let me add one final thought. This is what I believe seals the deal — what Americans call “the kicker.” Keller rightly asserts that “Jesus Christ has all the powers and functions of ministry in himself ” (p. 203). This is precisely the image that Paul wants to convey in Ephesians 4 when he talks about the ascension and Christ’s gifting of his church. Let me show you how the principle of Christ’s innate ministry is reflected through the lens of the APEST model (instead of the tripartite model). Ponder these questions:

• Is Jesus an apostle? The answer is, yes, of course — he is “the sent one” (variation of the root word apostellō). He founds the movement and keeps it together, and he is actually called “our apostle” in Hebrews 3:1. He is the archetypal apostle. Check!

• Is Jesus a prophet? Yes, undoubtedly. A major element of his ministry is to call people to repent and render allegiance and faithfulness to God. Check!

• Is Jesus an evangelist? Yes, in fact he is the good news, and he came to seek and to save the lost, to give eternal life, and so forth. Check!

• Is he a shepherd? Yes, definitely — he is the Good Shepherd. He creates and sustains the new covenant community. Check!

• Is he a teacher? No brainer — of course. Rabbi? Check!

This is not stretching it at all. We can legitimately say that Jesus is the perfect embodiment of APEST. In light of Ephesians 4, we can say it is the ministry of Christ (as archetypal and embodied APEST) that is expressed through the body of Christ, and this ministry should have a fivefold form among his people. This is not merely charismatic, Spirit-empowerment in view here; it is the very ministry of Christ in and through his people. I believe this understanding changes the game. Our understanding of the functions of the body of Christ are at stake here — referred to by some as the marks or characteristics of a church.

Here is the one-billion-dollar question: How can we expect to extend the impact of Jesus’ ministry if we only do it in two forms and not in the full five envisioned in Scripture? If Jesus is the original and originating APEST, how can the body of Christ truly embody his ministry in just shepherding and teaching forms? The clear answer from Ephesians 4:1 – 16 is that it cannot, and herein lies the reason for many of the dysfunctions in today’s church. At the same time, we find here one of the major keys to unlocking the dormant movemental potential of the church.

Today’s Apostolic Movements

Let me conclude with a few general statements about apostolic movements and their importance for us today.

1. Jesus has given the church everything it needs to get the job done. I believe we are coded for world transformation. This is what Jesus intended for us (see Matt 16), and the gospel implies it — that our ultimate goal is cosmic transformation (see Eph 1; Col 1). We can’t take this out even if we wanted to because Jesus put it in there. In this sense, the church is its own answer. We need to learn to attend to how God designed us to be. This means the paradigm shift is as much a theological discernment process as a practical and missiological one.

2. Every believer carries within them the potential for world transformation — a truth made clear as we observe how God uses ordinary people in movements (e.g., in the New Testament, in the early church, among the Celts, in Methodism, in the Chinese underground movements, and the like). How else can we explain the fact that uneducated Chinese peasants are changing the world? Consider this: In every seed is the potential for a tree, and in every tree the potential for a forest, but all of this is contained in the initial seed. In every spark there is a potential for a flame, and in every flame is the potential for conflagration, but all of this is potentially contained in the originating spark.

So it is with each believer among God’s people. All of the potential for movement is already present in God’s people; our job is to bring it out. One underground church in China puts it this way: “Every believer is a church planter; every church is a church-planting church.” Folks, this ought to change the way we see God’s people — men and women, poor and rich, young and old, white and black.

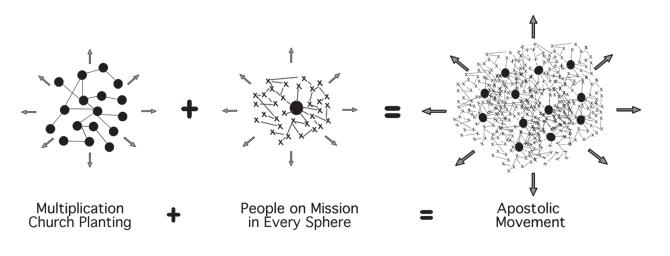

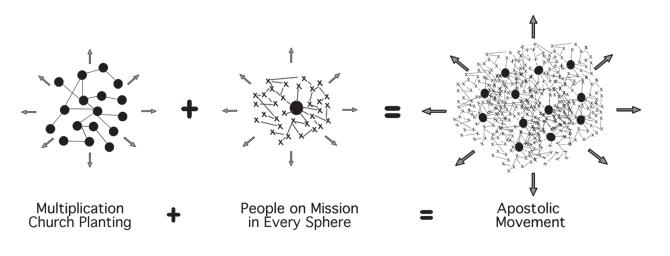

3. Movements only succeed to the degree that they legitimize and activate the ministry of all of God’s people. Each person can be an “ordinary hero.” I would go as far as to say that the agency of all believers is the secret weapon that God brings out in times of movemental breakthrough. Everyone gets to play! In one of my books, I suggest that movements need the organized, distinctly ecclesial aspects associated with viral church planting, but they also need to activate the agency of all believers in every sphere and domain of society.10 When these two aspects come together at the right time and under the right spiritual conditions, we have the possibility for real movements to develop. It can be illustrated in this way:

The diminishment of the agency of all believers and the corresponding professionalization and clericalization of ministry have led to a loss of movement dynamic and an increased control in the church as an institution. In China, the clergy had to be forcibly removed for the church to recover its dormant potentials and transition into hyperbolic growth and impact. Clericalism seems to be a huge blocker to movemental dynamics, as was true for early Methodism and Pentecostalism as well. When will we learn from the lessons of the past?

4. Movements are essentially DNA-based organizations. Like all living systems, organizations replicate and maintain their integrity based on the internal coding present in every part of the organization. Each living cell has the coding for the whole body.

Organizations are only movements to the degree that they do this. Just follow the logic of DNA. If you get the core practices and ideas right and embed them deeply into every possible part of the system, you can step back, pray like mad, and let go. As you do this, remember to practice high accountability and low control.

To use another metaphor, movements are more like starfish than they are spiders. You can kill a spider by taking its head off. Spiders have a centralized control center. On the other hand, when a starfish is cut up, it will produce more starfish. Each part carries the potential for the whole.

5. While all five APEST ministries have a role that is vital and nonnegotiable, the apostolic in particular is the key to an apostolic movement — the kind we see on the pages of the New Testament. This is not an emphasis of importance or priority; it is one of purpose and design. By nature and calling, the apostolic person (the sent one) follows the innate impulses of his or her sentness and pushes the system to the edges in order to establish Christianity onto new ground. They engage in church planting, not just personal evangelism. They incessantly network and seek to maintain core unity within the context of increasing geographic and cultural diversity. The result is a burgeoning movement, the likes of which Tim Keller brilliantly espouses in these chapters and lives out through the Redeemer City to City movement worldwide.

The pattern is clear: Remove apostolic influences, and you won’t get apostolic movement. They are inextricably related. The wonderful irony is that though Keller admits to being something of a cessationist regarding his theology of Ephesians 4,11 he remains one of the best examples of today’s apostolic leaders. He demonstrates exactly why we need this kind of ministry in our time.

A ship in harbor is safe, but that is not what ships are built for.

John A. Shedd, “Salt from My Attic”