Emotion and Valence

AS MY STARTING POINT in this chapter, I explore an aspect of time-consciousness that was neglected in the previous chapter—the future-oriented aspect of protention. As we will see, there is a strong link between protention and emotion, so that affect plays an important role in the generation of the flow of experience and action.

In thinking about the structure of time-consciousness, it is easy to assume that protention is simply the reverse or inverse of retention and thus that the threefold structure of temporality is symmetrical. But this cannot be the case for several reasons (Gallagher 1998, p. 68; Varela 1999, p. 296).

First, protention is intentionally “unfulfilled,” which means that what it targets is absent or not fully present. Protention aims at the “not yet,” and so its content has yet to be determinately filled in. Retention, in contrast, is “fulfilled,” for it targets what was just there, and hence its content is determinate. Protention is intentionally directed toward a nonactual and immediately imminent phase of what is happening, retention toward an immediately elapsed and previously actual phase. Retention is thus determinate in its content in a way protention cannot be. Although protention intends the future in a more or less definite way, it is nonetheless open and indeterminate, for what it intends has yet to occur.

Second, it follows that protention is a bounded domain, though not a continuum. Retention always involves a continuum, the retention of previous retentions. Protentions cannot form a continuum in this way, for the protentions that would be intended by the currently operating protention have not yet occurred. In Gallagher’s words: “Protention cannot be a gradual and orderly falling into obscurity; it must be an unregulated, relatively indeterminate, and temporally ambiguous sense of what is to come” (1998, p. 68). Whereas retentions continually recede into the past and intentionally contain each other, protention is an open horizon of anticipation.

Finally, emotion is integral to protention, for protention always involves motivation, an affective tone, and an action tendency or readiness for action. It is this link to emotion that I intend to explore in this chapter.

Let us begin with the idea that protention is motivated. On the one hand, retention motivates protention, or more precisely, retentional contents motivate protentional contents, for one’s anticipation of what is about to happen in the immediate future is based on one’s retention of what has just happened. For example, my current experience of watching a flock of birds fly across the sky continually protends a certain direction to their flight, based on my continual retention of where they have just been. On the other hand, protentions motivate retentions, for what is protended affects what is retained. I protend the flight path of the birds, and these protentions are retained as fulfilled (if the flight path is as I anticipate) or unfulfilled (if something unexpected happens). Retention thus includes not simply retention of what has just occurred, but also retention of just-having-been protending in this or that way. Retention always includes retention of protention and of the way protention is fulfilled or unfulfilled (Rodemeyer 2003).

The motivational relation between retention and protention is thus highly nonlinear. Retention motivates protention, which affects retention, which motivates protention, and so on and so forth, in a self-organizing way that gives temporal coherence to experience. If we abstract away from the specific retentional and protentional contents, and consider retention and protention at a purely formal or structural level, then we can say that, regardless of their contents, retention continually modifies protention and protention continually modifies retention. This mutual modification is reciprocal, though not symmetrical. Retention modifies the “style” of protention, but protention cannot retroactively influence retentions that have already occurred. Rather, “actual protentioning will affect retentioning that has not yet occurred, in the sense that retentioning will always be a retentioning of just-having-been protentioning, but not vice-versa” (Gallagher 1998, p. 68). In this way, the flow of experience is self-organizing, forward moving, irreversible, and motivationally structured.

In this chapter, I look at the role of affect and action tendencies in the generation of this flow. Their importance in relation to protention can be indicated now by noting that the protentional “not yet” is always suffused with affect and conditioned by the emotional disposition (motivation, appraisal, affective tone, and action tendency) accompanying the flow (Varela 1999, p. 296). From a neurophenomenological perspective, these emotional aspects of protention act as major boundary and initial conditions for the neurodynamical events at the 1/10 and 1 scales described in the previous chapter. For this reason, Varela describes protention as a global order parameter that shapes the dynamics of large-scale integration in the brain.1 Whereas retention corresponds to the dynamical trajectories as realized by the current state of the system, protention corresponds to the global order parameters for anticipation that condition the subsequent directions of the trajectories.

Before going more deeply into these ideas, let me connect them to the theme of this book, the deep continuity of life and mind. In Chapter 6 we saw that biological time is fundamentally forward-looking and arises from autopoiesis and sense-making. Life is asymmetrically oriented toward the future because the realization of the autopoietic organization demands incessant metabolic self-renewal. As Jonas (1968) declares, echoing Spinoza, life’s basic “concern” is to keep on going. This immanent purposiveness of life is recapitulated in the temporality and intentionality of consciousness. Consciousness is a self-constituting flow inexorably directed toward the future and pulled by the affective valence of the world. What I wish to explore now is how this forward trajectory of life and mind is fundamentally a matter of emotion.

In a groundbreaking paper on emotion and consciousness, neuropsychologist Douglas Watt (1998) describes emotion as a “prototype whole brain event,” a global state of the brain that recruits and holds together activities in many regions, and thus cannot have simple neural correlates. We can take this point one step further by saying that emotion is a prototype whole-organism event, for it mobilizes and coordinates virtually every aspect of the organism. Emotion involves the entire neuraxis of brain stem, limbic areas, and superior cortex, as well as visceral and motor processes of the body. It encompasses psychosomatic networks of molecular communication among the nervous system, immune system, and endocrine system. On a psychological level, emotion involves attention and evaluation or appraisal, as well as affective feeling. Emotion manifests behaviorally in distinct facial expressions and action tendencies. Although from a biological point of view emotion comprises mostly nonconscious brain and body states, from a psychological and phenomenological point of view it includes rich and multifaceted forms of experience.2

In the face of this complexity, some scientists (LeDoux 1996) and philosophers (Griffiths 1997) have argued that although there are emotions, there is no such thing as emotion. The reason they cite is the absence of a unified category of phenomena to which the word “emotion” refers. Although one can point to particular emotions, notably the so-called basic emotions of fear, surprise, anger, disgust, sadness, and joy (according to one list), and to neural systems that mediate them, there is no emotion “natural kind” to which they belong. Nevertheless, these theorists continue to use the word “emotion” to describe their subject matter and to relate biological and psychological levels of explanation, thereby showing the theoretical or at least expository usefulness of the term.3

It is still an open question, however, which theoretical framework can best account for the diverse aspects of emotion—from the biological to psychological to phenomenological—in conceptually and empirically profitable ways. Dynamic systems approaches to emotion look especially promising in this light (Lewis 2000, 2005; Lewis and Granic 2000). Besides the affinity between these approaches and the enactive approach, there are important points of convergence between dynamic systems approaches to emotion and phenomenological ones, as we will see later in this chapter.

Etymology tells us that the word “emotion” (from the Latin verb emovere) literally means an outward movement. Emotion is the welling up of an impulse within that tends toward outward expression and action. There is thus a close resemblance between the etymological sense of emotion—an impulse moving outward—and the etymological sense of intentionality—an arrow directed at a target, and by extension the mind’s aiming outward or beyond itself toward the world. Both ideas connote directed movement. This image of movement remains discernible in the abstract, cognitive characterization of intentionality in phenomenology. As discussed in Chapter 2, intentionality is no mere static relation of aboutness, but rather it is a dynamic striving for intentional fulfillment. In genetic phenomenology, this intentional striving is traced back to its roots in “originally instinctive, drive related preferences” of the lived body (Husserl 2001, p. 198). Husserl calls this type of intentionality “drive-intentionality” (Triebintentionalität) (see Mensch 1998). Patocka calls it “e-motion.” This term connotes movement, its instigation by “impressional affectivity,” and the dynamic of “constant attraction and repulsion” (Patocka, 1998, p. 139). Walter Freeman recognizes this bond between emotion and intentionality, making it the starting point for his enactive or “activist-pragmatist” approach to emotion:

A way of making sense of emotion is to identify it with the intention to act in the near future, and then to note increasing levels of the complexity of contextualization. Most basically, emotion is outward movement. It is the “stretching forth” of intentionality, which is seen in primitive animals preparing to attack in order to gain food, territory, or resources to reproduce, to find shelter, or to escape impending harm . . . The key characteristic is that action wells up from within the organism. It is not a reflex. It is directed toward some future state, which is being determined by the organism in conjunction with its perceptions of its evolving condition and its history. (Freeman 2000, p. 214)

It is illuminating to compare this starting point with a different neuroscientific one, that of Joseph LeDoux (1996). According to LeDoux, “the word ‘emotion’ does not refer to something that the mind or brain really has or does,” because “There is no such thing as the ‘emotion’ faculty and there is no single brain system dedicated to this phantom function.” Instead, “the various classes of emotions are mediated by separate neural systems that have evolved for different reasons . . . and the feelings that result from activating these systems . . . do not have a common origin” (1996, p. 16). In short, although there are lots of emotions, there is no such thing as emotion (p. 305). LeDoux states explicitly the premise on which this line of reasoning rests: “the proper level of analysis of a psychological function is the level at which that function is represented in the brain” (p. 16). From an enactive perspective, however, this conception of a function—a mechanism that implements some mapping from input (sensory stimulation) to output (motor response)—presupposes that we are treating the brain as a heteronomous device, not an autonomous system. As Freeman writes, linear input-output models leave “no opening for self-determination” (1999b, p. 147).

Self-determining or autonomous systems, as we have seen, are defined by their organizational and operational closure, and thus do not have inputs and outputs in the usual sense. For these systems, the linear input/output distinction must be replaced by the nonlinear perturbation/response distinction. From an enactive perspective, brain processes are understood in relation to the circular causality of action-perception cycles and sensorimotor processes. Hence emotion is not a function in the input-output sense, but rather a feature of the action-perception cycle—namely, the endogenous initiation and direction of behavior outward into the world. Emotion is embodied in the closed dynamics of the sensorimotor loop, orchestrated endogenously by processes up and down the neuraxis, especially the limbic system.4 The enactive approach can thus provide a theoretically significant, superordinate concept of emotion and can ground that concept in large-scale dynamic properties of brain organization.

The guiding question for an enactive approach to emotion is well put by Freeman: “How do intentional behaviors, all of which are emotive, whether or not they are conscious, emerge through self-organization of neural activity in even the most primitive brains?” (Freeman 2000, p. 216).

Consideration of this question needs to begin with features of brain organization. The overall organization of the brain reflects a principle of reciprocity: if area A connects to area B, then there are reciprocal connections from B to A (Varela 1995; Varela et al. 2001). Moreover, if B receives most of its incoming influence from A, then it sends the larger proportion of its outgoing activity back to A and only a smaller proportion onward (Freeman 2000, p. 224). Nevertheless, traditional neuroscience has tried to map brain organization onto a hierarchical, input-output processing model in which the sensory end is taken as the starting point. Perception is described as proceeding through a series of feedforward or bottom-up processing stages, and top-down influences are equated with back-projections or feedback from higher to lower areas. Freeman aptly describes this view as the “passivist-cognitivist view” of the brain.

From an enactive viewpoint, things look rather different. Brain processes are recursive, reentrant, and self-activating, and do not start or stop anywhere. Instead of treating perception as a later stage of sensation and taking the sensory receptors as the starting point for analysis, the enactive approach treats perception and emotion as dependent aspects of intentional action, and takes the brain’s self-generated, endogenous activity as the starting point for neurobiological analysis. This activity arises far from the sensors—in the frontal lobes, limbic system, or temporal and associative cortices—and reflects the organism’s overall protentional set—its states of expectancy, preparation, affective tone, attention, and so on. These states are necessarily active at the same time as the sensory inflow (Engel, Fries, and Singer 2001; Varela et al. 2001).

The working hypothesis of experimental neurophenomenology, as we saw in the previous chapter, is that aspects of these states can be phenomenologically tracked in humans, and the resulting first-person data can be used to guide neurodynamical experimentation. Whereas a passivist-cognitivist view would describe such states as acting in a top-down manner on sensory processing, from an enactive perspective top down and bottom up are heuristic terms for what in reality is a large-scale network that integrates incoming and endogenous activities on the basis of its own internally established reference points. Hence, from an enactive viewpoint, we need to look to this large-scale dynamic network in order to understand how emotion and intentional action emerge through self-organizing neural activity.

Walter Freeman’s work is especially relevant here. Building on his pioneering research in neurodynamics over many years, he has proposed an enactive and neurodynamical model of what Merleau-Ponty calls “the intentional arc subtending the life of consciousness” (see Chapter 9). Freeman’s model contains five circular causal loops, comprising brain, body, and environment, but centered on the limbic system, the brain area especially associated with emotion (see Figure 12.1). Emotion, intention, and consciousness emerge from and are embodied in the self-organizing dynamics of these nested loops.

Figure 12.1. Walter Freeman’s model of the intentional arc arising from the dynamic architecture of the limbic system. Reprinted with permission from Walter Freeman, “Consciousness, Intentionality, and Casuality,” Journal of Consciousness Studies 6/11–12 (1999): 150, fig. 4.

At the most global level is the “motor loop” between organism and environment. This loop consists of the sensorimotor circuit leading from motor action in and through the environment, and back to the sensory stimulation resulting from movement. Motor action involves directed arousal and search, and expresses the organism’s states of expectancy. The sensory stimuli that the organism receives depend directly on its motor action, and how the organism moves depends directly on the sensory consequences of its previous actions. Merleau-Ponty, in The Structure of Behavior, recognized the importance of this loop: “since all stimulations which the organism receives have in turn been possible only by its preceding movements which have culminated in exposing the receptor organ to the external influences, one could . . . say that . . . behavior is the first cause of the stimulations. Thus the form of the excitant is created by the organism itself, by its proper manner of offering itself to actions from outside” (1963, p. 13).

Whereas the motor loop travels outside the brain and body into and through the environment, the “proprioceptive loop” travels outside the brain but is closed within the body. This loop consists of pathways from sensory receptors in the muscles and joints to the spinal cord, cerebellum, thalamus, and somatosensory cortex. Freeman (2000) also describes this loop as an interoceptive one. Interoception in this context is best understood as the sense of the physiological condition of the entire body, not just the viscera, and involves distinct neural pathways in the spinal cord, brainstem, thalamus, and insula (Craig 2002).

The three remaining loops of the model are all within the brain. If we begin on the sensory side, then we first need to remember that sensory stimuli occur in a context of expectancy and motor activity. When a stimulus arrives, the activated receptors transmit pulses to the sensory cortex, where they induce the construction by nonlinear dynamics of an activity pattern in the form of a large-scale spatial pattern of coherent oscillatory activity. This pattern is not a representation of the stimulus but an endogenously generated response triggered by the sensory perturbation, a response that creates and carries the meaning of the stimulus for the animal. This meaning reflects the individual organism’s history, state of expectancy, and environmental context.

These meaningful dynamic patterns constructed in the cortex converge into the limbic system through the entorhinal cortex, an area of multisensory convergence that receives and combines activity from all primary sensory areas of the cortex. The dynamic activity patterns are spatially and temporally sequenced in the hippocampus, an area known to be involved in memory and the orientation of behavior in space and time. Reciprocal interaction between the entorhinal cortex and the hippocampus (the “spacetime loop”) creates a unified gestalt (in the form of a large-scale, coherent oscillatory pattern), which is transmitted both to the motor systems (the “control loop”), thereby mobilizing the visceral and musculoskeletal activities needed for action and emotional expression, and back to the sensory systems through corollary discharges (the “reafference loop”), thereby preparing them for the expected consequences of motor actions.

Freeman calls this sensory preparation process “preafference” and sees it as the neural basis for what we subjectively experience as attention and expectancy (1999a, p. 34). Expectancy, in Freeman’s sense, corresponds closely to the phenomenological notion of protention: it is not a distinct cognitive act, but rather an intentional aspect of every cognitive process. Freeman holds that preafference “provides an order parameter that shapes attractor landscapes, making it easier to capture expected or desired stimuli by enlarging or deepening the basins of their attractors” (1999a, p. 112). This view of preafference agrees with Varela’s idea that protention provides an order parameter for the neurodynamics of sensorimotor and neural events at the 1/10 and 1 scales of duration.

Figure 12.1 shows the flow of activity going in both feedforward (counterclockwise) and feedback (clockwise) directions. Freeman hypothesizes that the forward direction consists of microlevel fluctuations in neuronal activity that engender new macroscopic states, whereas the feedback direction consists of macroscopic order parameters that constrain the microlevel activities of the forwardly transmitting neuronal populations. These feedforward and feedback flows thus correspond, respectively, to the local-to-global and global-to-local sides of emergence. Cutting this circular causality into forward and feedback arcs is heuristic, for at any moment there is only system causation, whereby the system moves as a whole (see Appendix B).

Freeman also relates this model to consciousness. He proposes that in addition to the large-scale activity patterns that emerge through the nonlinear dynamics of the spacetime loop, there is another higher-order pattern at the hemispheric level of the brain, in which the lower-order activity patterns of the limbic system and sensory cortices are components. This higher-order pattern organizes and constrains the lower-order ones. Freeman hypothesizes that this type of globally coherent, spatiotemporal pattern of activity, which takes on the order of a tenth to a quarter of a second to arise (Varela’s 1/10 and 1 scales), is the brain correlate of a state of “awareness,” and that “consciousness” consists of a sequence of such states. While emotion (the internal impetus for action) and intentional action constitute the cognitive flow in the feedforward direction (see Figure 12.1), awareness and consciousness constitute the cognitive flow in the feedback direction. Awareness, according to this model, far from being epiphenomenal, plays an important causal role. Its role is not as an internal agent or homunculus that issues commands, but as an order parameter that organizes and regulates dynamic activity. Freeman and Varela thus agree that consciousness is neurally embodied as a global dynamic activity pattern that organizes activity throughout the brain. Freeman describes consciousness as a “dynamic operator that mediates relations among neurons” and as a “state variable that constrains the chaotic activities of the parts by quenching local fluctuations” (1999a, pp. 132, 143). What Varela’s neurophenomenology of time-consciousness adds to this view is a proposal about how the sequence of such transitory activity patterns (corresponding to discrete states of awareness) can also constitute a flow thanks to their retentional-protentional structure.

Let us return to emotion. As Freeman’s model indicates, “emotion is essential to all intentional behaviors” (Freeman 2000). Consider perception. According to the dynamic sensorimotor approach (see Chapter 9), in perceiving we exercise our skillful mastery of sensorimotor contingencies—how sensory stimulation varies as a result of movement. This approach to perception focuses on the global sensorimotor loop of organism and environment. We can now appreciate, however, that this loop contains numerous neural and somatic loops, whose beating heart (in mammals) is the endogenous, self-organizing dynamics of cortical and subcortical brain areas. Sensorimotor processes are motivated and intentionally oriented thanks to endogenous neural gestalts that emerge from depths far from the sensorimotor surface. Hence, according to the enactive approach, sensorimotor processes modulate, but do not determine, an ongoing endogenous activity, which in turn infuses sensorimotor activity with emotional meaning and value for the organism.

My aim now is to sketch a neurophenomenological way of thinking about emotion by connecting these neurodynamical ideas to the phenomenology of emotion experience. To frame the discussion, I will draw from emotion theorist Marc Lewis’s dynamic systems model of emotional self-organization (Lewis 2000, 2005).

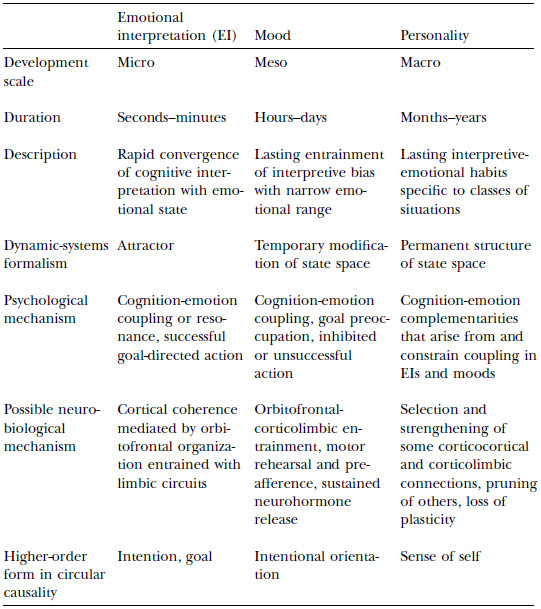

Lewis (2000) proposes a developmental model of emotional self-organization at three time-scales—the microdevelopment of emotion episodes at a time-scale of seconds or minutes, the mesodevelopment of moods at a time-scale of hours or days, and the macrodevelopment of personality at a time-scale of months and years (see Table 12.1). At each scale, emotional self-organization is modeled as an emergent cognition-emotion interaction. Cognition includes perception, attention, evaluation, memory, planning, reflection, and decision making, all of which are aspects of what emotion theorists call “appraisal,” the evaluation of a situation’s significance. Emotion includes arousal, action tendencies, bodily expression, attentional orientation, and affective feeling.

Yet cognition and emotion are not separate systems, for two reasons (Lewis 2005). First, there is a large amount of anatomical overlap between the neural systems mediating cognition and emotion processes, and these systems interact with each other in a reciprocal and circular fashion, up and down the neuraxis. Second, the emergent global states to which these interactions give rise are “appraisal-emotion amalgams,” in which appraisal elements and emotion elements modify each other continuously. Such modification happens at each time-scale, through reciprocal interactions between local appraisal and emotion elements, and circular causal influences between local elements and their global organizational form.

To explore the parallels between this model and phenomenological ideas, we need to look at the model’s three time-scales of emotional self-organization in more detail. At the microlevel, emotional self-organization takes the form of an emergent “emotional interpretation” (or EI), a rapid convergence of a cognitive interpretation of a situation and an emotional state (happiness, anger, fear, shame, pride, sympathy, and so forth). Cognitive and emotional processes modify each other continuously on a fast time-scale, while simultaneously being constrained by the global form produced by their coupling in a process of circular causality. This emergent form, the emotional interpretation, is a global state of emotion-cognition coherence, comprising an appraisal of a situation, an affective tone, and an action plan. Lewis also describes this higher-order form, drawing on Freeman’s ideas, as a global intention for acting on the world. This global intention is not only a whole-brain event, but also a whole-organism event. As Freeman writes, “Considering the rapidity with which an emotional state can emerge—such as a flash of anger, a knife-like fear, a surge of pity or jealousy—whether the trigger is the sight of a rival, the recollection of a missed appointment, an odor of smoke, or the embarrassing rumble of one’s bowel at tea, the occasion is best understood as a global first-order state transition involving all parts of the brain and body acting in concert” (2000, p. 224).

Table 12.1 Three scales of emotional self-organization, showing parallels and distinctions across scales and hypothesized psychological and neurobiological mechanisms.

Source: Marc D. Lewis, “Emotional Self-Organization at Three Time-Scales,” in Marc D. Lewis and Isabela Granic, eds., Emotion, Development, and Self-Organization (Cambridge, 2000), p. 59. Reprinted with the permission of Cambridge University Press.

According to Lewis’s (2005) model, the emergence of an emotional interpretation begins as a fluctuation in the flow of intentional action, triggered by a perturbation (external or internal), which eventually disrupts the orderliness of the current emotional interpretation. Rapid processes of self-amplification through positive feedback ensue, followed by self-stabilization through negative feedback and entrainment, leading to the establishment of a new orderliness in the form of a new momentary emotional interpretation and global intention. This self-stabilization phase is the precondition for learning, the consolidation of long-term emotion-appraisal patterns.

There are thus three principal phases in the emergence of an emotional interpretation—a trigger phase, a self-amplification phase, and a self-stabilization phase—as well as an additional fourth learning phase that extends the influence of the present emotional interpretation to future ones. Lewis likens the whole process to a bifurcation from one attractor to another in an emotion-cognition state space. He has recently presented a neuropsychological model of some of the brain areas and large-scale neural-integration processes involved (Lewis 2005).5

Although Lewis emphasizes the importance of affective feeling as a motivational component of emotion, he does not explore the phenomenology of affect in relation to the emergence of an emotional interpretation. It is therefore worth investigating the resonance between Lewis’s model and the genetic phenomenology of affect.

To explore this resonance, we need to recall a few key ideas from genetic phenomenology. Passive synthesis is the term Husserl uses to describe how experience comes to be formed as one is affected precognitively. He draws a distinction between “passivity” and “receptivity” (Husserl 2001, p. 105). Passivity means being involuntarily affected while engaged in some activity. Receptivity means responding to an involuntary affection (affective influence) by noticing or turning toward it. Every receptive action presupposes a prior affection (2001, p. 127). Husserl writes: “By affection we understand the allure given to consciousness, the peculiar pull that an object given to consciousness exercises on the ego” (2001, p. 196). “Allure” does not refer to a causal stimulus-response relation but to an intentional “relation of motivation” (Husserl 1989, p. 199). Attention at any level is motivated by virtue of something’s affective allure. Depending on the nature and force of the allure, as well as one’s motivations, one may yield to the allure passively or involuntarily, voluntarily turn one’s attention toward it, or have one’s attention captured or repulsed by it.

Receptivity is the lowest active level of attention, at the fold, as it were, between passivity and activity—a differentiation that can be made only relatively and dynamically, not absolutely and statically. Allure implies a dynamic gestalt or figure-ground structure: something becomes noticeable, at whatever level of attention, owing to the strength of its allure; it emerges into affective prominence, salience, or relief; while something else becomes unnoticeable owing to the weakness of its allure (Husserl 2001, p. 211). This dynamic interplay of passivity and activity, affection and receptivity, expresses a “constantly operative” intentionality (Husserl 2001, p. 206) that does not have an articulated subject-object structure (Merleau-Ponty 1962, p. xviii).

With these ideas in place, we can turn to investigate the microdynamics of affect at the 1 scale. In the previous chapter, we saw that our experience of the present moment depends on how the brain dynamically parses its own activity by forming transient, large-scale neural assemblies that integrate sensorimotor and neural events occurring at the 1/10 scale. Recall also that in the flow of habitual activity changes can occur, sometimes as smooth transitions, sometimes as breakdowns and disruptions. In Merleau-Ponty’s terms, the leading “I can” can change from moment to moment as we rapidly switch activities.

From a neurodynamical perspective, when such switches occur the global neural assembly that is currently dominant comes apart through desynchronization, and a new moment of global synchronization ensues. Varela proposes that these switches are driven by emotion and manifest themselves in experience as dynamic fluctuations of affect (Varela 1999; Varela and Depraz 2005). In the flow of skillful coping, we switch activities as a result of the attractions and repulsions we experience prereflectively (Rietveld 2004). Such emotional fluctuations act as control parameters that induce bifurcations from one present moment of consciousness to another. In this way, emotion plays a major role in the generation of the flow of consciousness, and this role can be phenomenologically discerned in the microtemporality of affect.6

Varela and Depraz (2005) present such a phenomenology of affect in their paper, “At the Source of Time: Valence and the Constitutional Dynamics of Affect.” Their analysis proceeds on the basis of two examples of emotion experience. One is a singular experience of Varela’s—a “musical exaltation” experience while listening to the first few notes of a sonata at a concert.7 The other is a generic experience of “averting the gaze,” of shielding or hiding one’s eyes (se cacher les yeux), described evocatively by Merleau-Ponty in the early pages of The Visible and the Invisible (which are devoted to the “perceptual faith,” our everyday belief in the veracity of perception):

It is said that to cover one’s eyes so as to not see a danger is to not believe in the things, to believe only in the private world; but this is rather to believe that what is for us is absolutely, that a world we have succeeded in seeing as without danger is without danger. It is therefore the greatest degree of our belief that our vision goes to the things themselves. Perhaps this experience teaches us better than any other what the perceptual presence of the world is: . . . beneath affirmation and negation, beneath judgment . . . it is our experience, prior to every opinion, of inhabiting the world by our body . . . (1968, p. 28).

Varela and Depraz ask the reader to take a moment to reenact one’s own examples of this averting-the-gaze experience. Examples come readily to my mind—avoiding meeting someone’s eyes on the street who is about to ask for money; averting my eyes from a headline I can tell is upsetting before I have fully taken it in from the morning newspaper at my doorstep; or reflexively recoiling from a solitary angry face, snarling at me in bitter loneliness from a restaurant window as I walk by one sunny Christmas afternoon and inadvertently peer too long.

Following Watt (1998), Varela and Depraz point to a number of concurrent components of affect in such momentary emotion episodes. (In what follows I combine and rephrase elements from both Watt’s original presentation, which is given from the perspectives of emotion theory and affective neuroscience, and Varela and Depraz’s, which is more phenomenologically oriented.)

• A precipitating event or trigger, which can be perceptual or imaginary (a memory, fantasy), or both. (This component corresponds to the trigger phase in Lewis’s model of an emotional interpretation.)

• An emergence of affective salience, involving an evident sense of the precipitating event’s meaning. In emotion theory, this aspect of emotion is described as reflecting an appraisal, which can take form before the experience of affect (as part of the precipitating process), just after (as a post-hoc appraisal), and can interact continually and reciprocally with affect, through processes of self-amplification and self-stabilization (as emphasized by Lewis). The appraisal can be fleeting or detailed, realistic or distorted, empathetic or insensitive (and typically reflects some combination of these features). Much of the appraisal will be prereflective and/or unconscious.

• A feeling-tone, described in psychology as having a valence or hedonic tone along a pleasant/unpleasant polarity.

• A motor embodiment, in the form of facial and posture changes, and differential action tendencies or global intentions for acting on the world.

• A visceral-interoceptive embodiment, in the form of complex autonomic-physiological changes (to cardiopulmonary parameters, skin conductance, muscle tone, and endocrine and immune system activities).

Each of these five components can be discerned in my averting-the-gaze examples, especially the recoil from the angry face. Inadvertently seeing an angry face is a precipitating event or trigger. Faces, especially angry ones, have strong affective allure. Seeing a face as an angry face is an example of the rapid emergence of affective salience and appraisal, an emotional interpretation. The salience increases with the realization that the anger is directed at me—an elaboration of the emotional interpretation. A complex feeling-tone of startle, surprise, fear, and distress strikes like an electric shock. I turn my eyes and head to look away, and I quickly speed up my pace (motor embodiment). My global intention is to get away, though not to the point of feeling the need to escape physical danger (another appraisal). My gut contracts, my breathing becomes faster and shallower, my face becomes flushed and hot, and my muscles tense as I turn away and speed up my walk (visceral-interoceptive embodiment). At the same time I am overcome with the realization that Christmas is a painful and lonely time for many people, while feelings of sadness and sympathy for the lonely man, shame at my own insensitivity, and defensiveness at his aggression—all complex emotional interpretations with their own triggers, saliencies, appraisals, feeling-tones, and associated motor and visceral embodiments—rapidly alternate, reverberate, and seemingly reinforce one another, in a matter of seconds. As distance from the episode in space and time increases over the next few minutes and hours, a melancholy mood sets in, which affects me for the rest of the day, along with a feeling of resistance and an attempt to push the experience, now in the form of memory, from my mind. These longer-term, emotion-appraisal patterns arise at the mesoscale of mood, and condition and modulate my emotions for some time to come.

We can now see that the microdevelopment of an emotional interpretation contains within it a complex microdevelopment of affect. Husserl’s detailed phenomenological descriptions of this microdevelopment are highly suggestive of a self-organizing, dynamic process. He describes experience as subject to “affective force.” Affective force manifests as a rapid, dynamic transformation of experience, mobilizing one’s entire lived body. The transformation is one in the “vivacity of consciousness” or the “varying vivacity of a lived-experience” (Husserl 2001, §35, pp. 214–221). There are relative differences of vivacity belonging to an experience, depending on what is affectively efficacious and salient. There is a “gradation of affection,” from the affectively ineffective or nil to the affectively salient or prominent, with various intermediate gradations. The transformation in vivacity takes the form of a dynamic transition from the arousal or awakening of a responsive tendency to the emergence of affective salience. If we were to phrase this account in dynamic systems terms, then we could say that affective allure amounts to a parameter that at a certain critical threshold induces a bifurcation from passive affection (“passivity”) to an active and motivated orienting (“receptivity”) toward something emerging as affectively salient or prominent.8

Varela and Depraz maintain that this dynamics of affect has its “germ” or “source” in a “primordial fluctuation” of the body’s feeling and movement tendencies. This fluctuation manifests in any given instance as a particular movement tendency or motion disposition inhabited by a particular affective force. Patocka calls it an “e-motion” and describes it as a manifestation of the “primordial dynamism” of the lived body (Patocka 1998, pp. 40–42, 139). These fluctuations are valenced in the following sense. As movement tendencies, they exhibit movement and posture valences—toward/away, approach/withdrawal, engage/avoid, receptive/defensive. As feeling tendencies, they exhibit affective and hedonic valences—attraction/repulsion, like/dislike, pleasant/unpleasant, and positive/negative. As socially situated, they exhibit social valences—dominance/submission, nurturance/rejection. And as culturally situated, they exhibit normative and cultural valences, that is to say, values—good/bad, virtuous/unvirtuous, wholesome/unwholesome, worthy/unworthy, praiseworthy/blameworthy.

In summary, the dynamics of affect in an emotional interpretation can be traced back to fluctuations in valence, but valence needs to be understood not as a simple behavioral or affective plus/minus sign, but rather as a complex space of polarities and possible combinations (as in the chemical sense of valence) (see Colombetti 2005).

Having explored affect at the microscale of emotional interpretations, we can now turn to the mesoscale of moods. In Lewis’s model, moods comprise emotional continuity together with prolonged appraisal patterns. Whereas the movement from one emotional interpretation to another corresponds to a bifurcation from one attractor to another, the onset of a mood corresponds to a temporary modification of the entire emotion-cognition state space. Moods involve changes to the surface or global manifold of the state space, and thereby alter the landscape of possible attractors corresponding to possible emotional interpretations. “Self-organizing moods,” Lewis proposes, “at least negative moods—may arise through the entrainment of an interpretive bias with a narrow range of emotional states. This entrainment may evolve over occasions from the coupling of components in recurrent EIs, augmenting cooperativities that favor particular emotions and interpretations” (Lewis 2000, p. 48). Whereas the higher-order form of an emotional interpretation is a global intention for acting on the world, the higher-order form of a mood is an enduring intentional orientation.

An emotional interpretation, having the form of a global intention for action, can resolve itself in action (or an action type such as engagement or avoidance), but Lewis suggests that the intentional orientation of a negative mood persists because no action can be taken to resolve it: “Intentions (or real-time goals) prepare for actions, and actions dissipate intentions. But if actions are not attempted or are not effective, then emotional engagement with goal-relevant associations and plans may keep the goal alive, not as an immediate prospect but as a need or wish extending over time” (Lewis 2000, p. 49). Moods thus involve intentional and goal-directed content that cannot be reduced simply to the goal-directed content of the specific emotional interpretations they comprise.

If an emotional interpretation reflects a bifurcation or phase transition in the psychological (emotion-cognition) state space, whereas the global manifold of this space at any time reflects some mood, then it follows that mood is always present as a background setting or situation within which transient emotional interpretations occur.

This view of mood as an enduring, background intentional orientation is reminiscent of Heidegger’s description of mood as the most fundamental awareness one has of being in a world (1996, pp. 126–131). Yet there are differences too. For Heidegger, mood is not a form of object-directed experience, but rather a non-object-directed “attunement” (Stimmung) or “affectedness” (Dreyfus 1991, p. 168). Mood is omnipresent and primordial. It is always present, rather than being intermittent, and it is our original (most basic) way of being in the world. It preexists and is the necessary precondition for specific moods, such as fearfulness, depression, and contentment, which emerge out of primordial mood. Thus, from a Heideggerian point of view, the enduring intentional orientation of a specific mood, such as depression, could not arise unless we were already attuned to the world, that is to say, unless the world were already disclosed to us through primordial mood.

From a neurophenomenological point of view, Heidegger’s account is unsatisfying. For one thing, it is strangely disembodied, for the body plays no role in his account of mood and attunement, despite the attention he gives to fear and to the “fundamental mood” of anxiety. Second, in completely neglecting the microtemporality of affect in favor of a macroscopic analysis of mood and temporality, Heidegger provides no links from one scale to the other. Third, as Patocka points out, because mood for Heidegger involves understanding our place in the world in time, his account excludes animals, infants, and young children (1998, pp. 132–133). Mood is proper to “Dasein,” Heidegger’s term for individual human existence. Heidegger’s analysis of the “existential structures” constitutive of Dasein clearly indicates that Dasein is individual human existence of a mature and socialized adult form. Dasein is that being for whom being is an issue; that being who hides from the possibility of its own death, surrendering itself in everyday life to “the they,” the anonymous other, and who thereby lives inauthentically. In the case of animals and children, however, there is also subjectivity relating to the world (Patocka 1998, p. 133). Gallagher makes a similar observation:

on Heidegger’s description, it’s difficult to classify the neonate as an instance of Dasein, ontologically or experientially. If Dasein is das Man [“the they”], the infant has not yet had the chance to become das Man since it is only at the beginning of a socialization process. If Dasein has the possibility of authenticity as an alternative to inauthenticity, the infant has no such possibility. It can hardly be authentic or inauthentic since the possibility of its own death is not yet an issue for it. Perhaps the very young Dasein is not Dasein at all. (Gallagher 1998, p. 119)

There are two critical points here. First, as an “existential structure,” Heideggerian mood is largely static, for it has little if any genetic phenomenological depth. Second, if attunement or affectedness is supposed to be the most basic way of being in the world, then it would seem that Heidegger is leaving out something still more primordial, namely, the sensorimotor and affective sensibility of our bodily subjectivity (Patocka 1998, pp. 133–135). In short, Heidegger’s account neglects the lived body.

There remains the emotion macroscale of personality formation to consider in Lewis’s model. Emotional self-organization at this level is the formation of lasting interpretive-emotional habits specific to classes of situations. It involves permanent or long-lasting alterations to the basic shape of the emotion-cognition state space: “These include the initial establishment of attractors for recurrent EIs in infancy and the reconfiguration or replacement of those attractors during periods of personality transition” (Lewis 2000, p. 54). The emotional self-organization of personality development is explicitly intersubjective. Its higher-order form, which, due to circular causality, both emerges from and constrains moods and emotional interpretations, is a sense of personal self—“a subjective, intentional, thrusting forward into the world—this time lasting for months and years” (Lewis 2000, p. 57). According to this model, the sense of personal self is constituted by temporally extended, long-term patterns of habitual emotions linked with habitual appraisals, built up especially from moods.

In phenomenology, this sense of a personal self corresponds to what Husserl calls the “concrete ego.” By this he means the “I” that is constituted by “habitualities”—dispositional tendencies to experience things one way rather than another—as a result of general capabilities and sedimented experiences formed through active striving. Yet although this conception of self is of great importance for Husserl, and although his phenomenology is rich in analyses of affect and association, empathy and intersubjectivity, the Husserlian “concrete ego” is strangely lacking in personality. Overall there has been regrettably little analysis of emotion at the level of personality in phenomenology (unlike the Freudian or psychodynamic tradition).

In exploring the parallels and convergences between dynamic systems approaches to emotion and phenomenological approaches, I have been trying to sketch in a preliminary way what a neurophenomenology of emotion might look like. Lewis’s model is helpful in this regard because it describes emotion at a structural or formal level that is open to phenomenological and biological interpretation. Relying on the morphodynamical notion of form or structure, we can explore phenomenological accounts of the structure of emotion experience, while relating these accounts to psychological processes described by emotion theory and to neurobiological processes described by neurodynamics. Weaving together these multiple strands in this mutually enlightening way provides another example of the neurophenomenological approach to the structure of experience.