SWAGGER

DAWOUD BEY

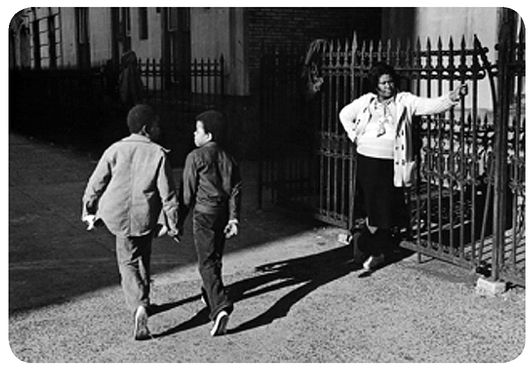

Harlem. Late afternoon, 1978. Fifth Avenue between 126th and 127th streets. A woman stands alone, serenely inhabiting the patch of sidewalk on which she stands. Perhaps she’s waiting for someone. Or perhaps she’s just waiting, resting at the end of the day before heading upstairs to prepare dinner for the people she loves. Or maybe there is no one, and she is simply collecting her thoughts. I can tell from the comfortable way she holds on to the iron fence that she knows this place well. For that moment, she owns that piece of concrete land. It is hers.

I see her one afternoon as I walk the streets of Harlem, looking for people and moments that exemplify this Black metropolis, this place that looms so large in the cultural imagination. I am attempting to make photographs that adequately inscribe, visually, the complexity of a people and a place. I am looking at the ways in which the past and present of Harlem bump up against each other, since all places are both the places they were and the places they are now. I am attracted by the light as much as I am by the woman herself, standing in the light even as the darkness looms around and behind her—she, so deep in thought.

I stand quietly and unobtrusively a few feet away from her and expose two frames of film, but I sense the photograph—indeed, the moment—needs something more, both to layer the pictorial narrative and to give the picture that is building a more complex sense of form. I look down the block to see who might be approaching, what elements I might be able to work into this picture that I am imagining, without knowing exactly what I am waiting for—only that I am waiting for something.

I see two young boys approaching, engaged animatedly in conversation, seemingly oblivious to the rest of the world. I know that if I take a step back, they will pass in front of me and also in front of the woman; they will inhabit the space in between the two of us. As they enter the frame, their gestures mirror each other; their stride is animated, exuberant, and confident. Their beings are full of a youthful bravado evident in their every move. They, too, now own this patch of sidewalk.

They are full of swagger. They are full of cool.

I take the picture, but cannot help thinking: When is swagger real and when is it perceived? Is Black swagger actually confidence and self-command going by a more loaded, and perhaps insidious, name? You know, a kind of cool surrogate of the less appealing “uppity”?

What happens to Black boys with too much swagger? Emmett Till is not here to answer on his own behalf. Visiting Mississippi from his home in Chicago one summer in 1955, the fourteen-year-old Till allegedly whistled at a white woman and was brutally murdered by several white men and thrown into the Tallahatchie River in Mississippi for his supposed transgression. Those folks who snuffed out his young Black life must have thought he was one seriously uppity little Negro. His swagger proved fatal.

swag • ger/’swag r/

r/

r/

r/Verb: Walk or behave in a very confident and typically arrogant or aggressive way: “he swaggered along the corridor.”

Noun: A very confident and typically arrogant or aggressive gait or manner.

When I was a young boy, growing up in the Black middle-class neighborhood of St. Albans, in Queens, New York, my mother used to make an example of my friend Michael’s older brother. He walked down the street with an exaggerated dip to his step, outfitted with a do-rag that held his processed “conk” in place. My mother would point him out derisively each time he passed our window. “Look at him,” she would say, shaking her head. She left no doubt in my mind that whatever Michael’s brother was, my brother Ken and I had better not even think about emulating or becoming it. She equated his swagger with a lack of substance masquerading as bravado. His swagger, which I did not then have a word for, she deemed arrogant, maybe even aggressive. Perhaps even dangerous.

Because the leap from “confident” to “aggressive” is perilously short. And aggressive people are threatening, right? So Black boys and men who carry themselves with assurance, with confidence, are perceived as dangerous—sometimes even to those in their own communities. Michael’s brother sure looked dangerous to me, like he knew his way around a switchblade, but he also looked like he gave full rein to what might be called the expressivity of the individual Black body, moving himself through the world with a power, grace, and style calculated to bring the body into alignment with its own stylistic and expressive powers through sheer celebratory comportment.

Which left me and my brother in a conundrum faced by Black men everywhere. How could we, boys of intelligence, boys raised to be confident and self-respecting, go about without raising the specter of danger so readily projected onto our Black male bodies? How could we be ourselves, in step, happy, owning any given piece of pavement, any given city block, without being pathologized? Criminalized. Because a certain kind of white person is intimidated by even the slightest whiff of Black swagger, no matter how subtly it is deployed.

The Black church is one place, at least, where a certain kind of Black swagger can be both safely expressed and ritualized. Calvary Baptist Church in Jamaica, New York, afforded me plenty of opportunities to see Black expressive swagger in this most ritualized context, week after week. Here, within a sacred space, swagger took on the function of both expressing and transporting the congregation, giving us a sense of our own swagger and power. At some point in the sermon, the preacher would start inserting personal anecdotes, using his own experiences to illustrate the lesson at hand. Invariably there came a point in these sermons where the language skirted the colloquial, and the minister told yet another story of some slight that “the white folks” had tried to visit upon him. Drawing himself up and deploying his full oratorical powers, he let it be known that they hadn’t been able to keep him in his place; his quiet grace and swagger had indeed seen him through the situation. And if those qualities had been sufficient to see him through, well, then, they must enough to get us through, too. And so we were primed to bring our own sense of swagger and inner power to whatever travails might confront us in the coming week.

But because I grew up firmly in the Black middle class, my own sense of personal and sartorial swagger was of a decidedly more muted kind, especially under the watchful and critical eyes of my mother and father. Their critique of the kinds of behavior likely to keep a Black boy from successfully moving through the world and toward a productive adulthood put little emphasis on outward expression while privileging the life of the mind and an outer life of decorum.

My brother and I were among the first group of Black kids to integrate all-white schools through busing; that is, we were taken out of the schools in our largely Black neighborhood and brought to schools in white neighborhoods, where presumably the quality of educational services being delivered was better. To survive in that world, especially in higher quarters, we had to become adept at what you might call a kind of behavioral code switching, the use of more than one language in speech. It soon became apparent that Black intellectual swagger was also suspect in such an environment, as I was constantly asked where I had copied my homework from, especially those assignments that required original thinking, such as writing a poem.

I was surrounded, though, by school friends for whom this was clearly not the case. Along with us Black middle-class kids who were bused from our parents’ homes, there were those Black kids who were, literally, from the other side of the Long Island Rail Road tracks. These were the kids who showed up each day in stylish beaver-skin hats (stuffed with plastic bags to keep the shape), alpaca knit sweaters (tucked—just so—into the waist of their slim-legged pants), playboy shoes (which were brushed several times a day to keep the suede fresh), and swagger for days! Clearly, there was no one at home telling these boys to tone down the swagger. They were a walking, moving celebration of expressive possibilities, their language, style, and presence signifying a celebration of every pore of their being, their uniqueness in these precincts of conformity.

Swagger, then, is a clear act of reclamation, a way to both reclaim and celebrate viscerally an aspect of self that has historically been eroded. Certainly the history of the Black presence in America is a traumatic one: Basic ownership of oneself was painfully and forcefully transferred. Merely looking a white person in the eye was for a long time cause for the worst sort of retribution—at worst, death. So swagger can be seen as a way to reclaim and celebrate that which was forcefully suppressed, even as the deeper swagger—that inner sense of cool and self-assurance that is the deeper swagger—was never completely eliminated from our racial DNA.

The institution of slavery, wherein begins Black contact with the Americas, deeply encoded a set of relationships designed to eliminate all vestiges of Black humanity and place the Black body in a subservient role of utter subjugation. Along with this, a visual culture emerged to support and further reinscribe this role of disempowered servitude. Thus were Blacks depicted in visual culture as foot-shuffling, watermelon-eating, buffoonish caricatures, their very humanity stripped away. Whether in films, in which docility was the main role for Blacks, or in the posters advertising grotesquely pantomimed minstrel shows, or in children’s books, where one would have encountered the happy and carefree little Sambo, there were precious few places where one would have encountered Black folks in all of their gloriously celebrated human complexity. While these images filled the public arena, Blacks always knew that those images were not theirs. And so the photographic image became important to the visual construction of Black humanity.

It was that urge to describe urban Black New York life through the camera that placed me in Harlem that long-ago afternoon, in the momentary presence of the stolid yet graceful Black woman and the carefree, swaggering Black boys. I had been inspired years earlier by my own initial encounter with the Black subject in photographs when I visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art at the age of sixteen to see the exhibition “Harlem on My Mind.” That experience set me on the path to wanting to shape my own pictorial view of the African American experience. I guess you could say the camera became my own way of exercising my subjectivity in the world through persistant visual authorship.

As I watched those two boys walk powerfully into the expansive black space of the picture and into the late-afternoon shadow, and then froze that moment for posterity, I realized I was giving full and glorious rein to their youthful Black swagger . . . and my own.