9

Gavin sits on the couch and I play my new song. I sing the four lines I wrote about Dr. M and I’m feeling proud but also embarrassed, because I hate the sound of my own voice.

“I’m done,” I say so he knows he can clap.

He opens his eyes, which are bright but not wet. He stares at me and he says in a not-so-excited way, “Very nice.”

“Did you cry?”

Gavin looks left and right and then straight at me. “Did I cry?”

“Yes.”

“No. I didn’t cry.”

I make a low rumbling noise in my mouth so Gavin will know that he’s supposed to ask me what’s wrong, but he doesn’t ask me, so I just tell him.

“I’m writing a song for the Next Great Songwriter Contest because I think it might be a good way to make sure I’m never forgotten.”

“What do you mean? Why would you be forgotten?”

“Because everyone forgets everything. They forget the name of the second person they ever kissed and they forget about what happened to those twins who were taken apart as babies and they even forget their own grandchildren. And it’s not fair because I would never do that.”

“I believe you.”

“But then I realized, it’s not people’s fault that they have crappy brains. That’s what reminders are for. Mom never forgets to pay the bills because she has a reminder on her calendar. And Dad remembers to put new batteries in our smoke alarm only because it starts beeping. And no one forgets Martin Luther King because he has his own holiday every year. It works the same way with songs. Everyone remembers John Lennon, even Grandma, because his songs are reminders. My song is going to be a reminder to everyone that they should keep me in their brainboxes, and I have less than two weeks to finish it.”

Gavin is frozen like a computer. It takes him a few seconds to get going again. “You’ve obviously spent a lot of time thinking about this.”

“Yes, I have.”

“But what does crying have to do with it?”

“A great song has to give you a strong feeling and one of the strongest feelings is wanting to dance. Even babies want to dance. The other strongest feeling is when you get sad and you cry because you hear a song and you remember everything that happened in your life. Which do you think is better for a song contest? Dancing or crying?”

Gavin hums like a humidifier and then he says, “Honestly, I don’t think people care whether they’re dancing or crying. A good song is a good song.”

“I don’t even know what that means.”

“When a song is good, everyone knows it. You can’t manufacture that. It’s like magic. You just have to let it happen.” He stops and thinks. “Actually, maybe you shouldn’t listen to me. I haven’t written a song in years.”

“John Lennon said he doesn’t believe in magic.”

“He said that? When?”

“In his song ‘God.’”

“Oh, right,” Gavin says. “Yeah, I don’t think he was talking about that kind of magic.”

I look down at my journal and I wonder if there’s magic on my page or not. Every once in a while Dad will play music from his college band and he’ll say how much he likes Gavin’s lyrics. He says Gavin was able to “capture life” with his words. There’s one Awake Asleep song when Gavin sings The night came to fight me, and even though I don’t know what the line means, I feel something when I hear it.

I hand Gavin my journal so he can read my lyrics about going to see the smart man in Arizona. He takes the journal carefully, like he’s worried it’s burning hot, and then he reads it and stays quiet for a long time after.

“Who’s the smart man?” he says.

“Dr. M.”

“Did Dr. M make you cry?”

“No. Why?”

He hands the journal back. “If that experience didn’t make you cry, how can you expect it to make other people cry? What makes you cry?”

“Scary movies, anything with dogs, bad teeth—”

“Whatever it is, put it in your song.”

I cried the day Charlotte moved away to Texas (Saturday, August 7, 2010), and I cried a few weeks ago when Mrs. Dresden said that time was up for our writing test but I wasn’t finished yet (Wednesday, May 15, 2013), and I cried when it was time to say good-bye to Grandma Joan (Saturday, October 8, 2011) and I also cried when Pepper went to sleep (Wednesday, March 25, 2009). I’ve never actually cried over a song before but I’ve seen it happen to other people.

It was a Friday and Dad was driving. His phone was on shuffle and John Lennon’s song “Mother” came on. Mom reached her hand to Dad’s neck and she left it there, tickling his skin. In the narrow mirror, Dad’s eyes looked shiny, and he stayed quiet the whole way home from Grandma Joan’s.

And I remember Dad once saying, “If a song hits you deep enough, you never get it out of your system.” That’s what I want so badly, to have my song go deep into everyone’s system, and that’s why making people cry is a good way to do it because it worked for the song “Mother” with my dad.

Gavin is staring at me. “What?” I say.

“Sorry,” he says, blinking his eyes. “I was just thinking about something.”

“Me too. I’ll tell you what I was thinking about if you tell me what you were thinking about.”

He lets out a short little breath, almost like a laugh that never gets started. “I’m not sure I want to share, if that’s okay.” He stretches his arm over his head and his bracelet slides down his wrist.

“That’s Sydney’s bracelet, right?”

He drops his arm and looks at the bracelet. “It is.”

Now I feel bad about asking him that question because I know just mentioning a certain name can put a person in a quiet mood. It happens with me when I hear someone say grandma and to Mom when someone talks about Sydney. Gavin is doing the same thing right now, just looking down and turning the bracelet around his wrist.

“When you see a memory,” Gavin says, “how much do you really see?”

“It depends what I was paying attention to at the time. Why? What do you want to know?”

“Nothing. I was just curious.”

“I don’t mind. I love remembering.”

He shakes his head, but I’m thinking maybe he’s just trying to be polite, like when someone offers you the last piece of cake and you say, “No, thank you,” even though you’d love an extra slice.

“I have an idea,” I say. “How about I tell you the stuff I remember about Sydney and then you can help me with my thing?”

“What’s your thing?”

“My song. Dad would normally help me but he’s not here and the Next Great Songwriter Contest says on their website that it doesn’t have to be just one songwriter, it can be a team, like Simon and Garfunkel, or Tegan and Sara, or Lennon and McCartney. So you can be McCartney and I’ll be Lennon. I’m the walrus.”

“I thought the walrus was Paul,” Gavin says.

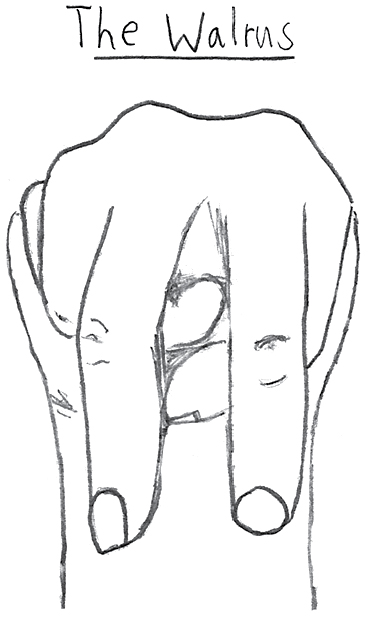

“No, John was the walrus. You can be the blackbird because that’s what Paul would probably be. I think we should have hand signals. Here’s mine.” I close my hand into a fist but I leave out my pointer finger and my middle finger and I hang them down like tusks.

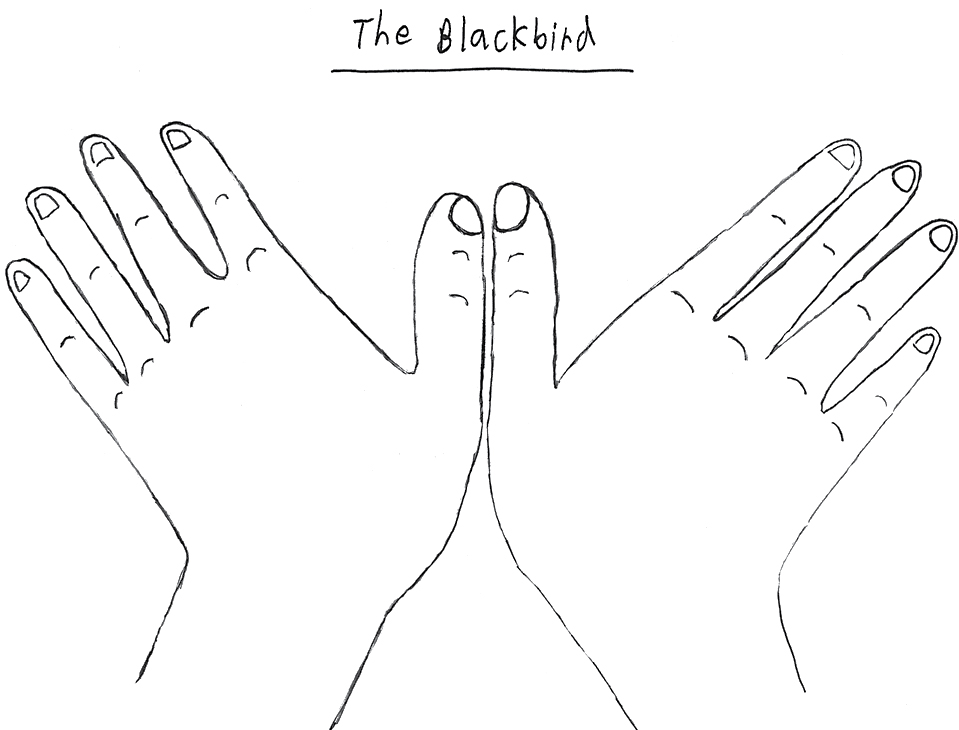

He isn’t sure what to do so I help him. I make it so his hands are stretched out and his thumbs are pressed together and I show him how to flap his palms like wings.

He drops his hands. “Look, Joan, I’m happy to help you however I can, but…”

I wait for him to finish his sentence, but he never does.

“Since we already worked on the song for a while, maybe we should do a memory now to make it fair,” I say.

“Now? I have a few things I should probably take care of.”

“We can start from the beginning, when I thought Sydney was a girl.”

Gavin looks like he wants to leave, but he also looks like he wants to stay. I’m not sure what to say next. I’m wondering if this is one of those times when I’m not letting up, which is something Mom is always warning me about. But Dad says not letting up can be a good thing if you’re lost in the wilderness or you’re trying to have a career as an artist.

Gavin relaxes a little bit on the couch and says, “What year was this?”

“It was 2008. A Monday. October twenty-seventh.”

He doesn’t say anything so I keep going.

“The doorbell rings and Mom presses the buzzer and she walks out the front door of our apartment and when she comes back upstairs she’s holding a box with a string. Sydney is standing behind her and I’m very surprised because when Mom said her friend Sydney was coming over for dinner, I was picturing a girl.”

“What was in the box?” Gavin says.

“Macaroons. Not the coconut kind. They were some other kind that I don’t like.”

“Macarons. They’re French. I didn’t know what they were either until Syd introduced me to them.” He seems interested now. “Go on. Do you know what he was wearing?”

“Yes. He’s wearing a peach button-down shirt and it’s tucked into his jeans and he has low-top brown shoes, the kind without laces, and his pants are rolled up and he isn’t wearing socks.”

“He never wore socks.” He presses his back into the couch cushion like he’s ready to get comfortable. “Did he say anything when he walked into the house?”

“He says, ‘Hello, Miss Joan. I’ve heard so much about you. Paige, you said she had horns. I don’t see any horns. Would you mind, dear?’ and then he touches the top of my head to see if I have any horns and I say, ‘I have a book about a unicorn,’ and Sydney says, ‘I love books and I love unicorns. How about you read the book to me after dinner?’ and I say, ‘I can only pretend-read,’ and he says, ‘I’ll do the reading and you can be my page turner,’ and then Dad comes into the room and Sydney starts talking to him.”

“That’s unbelievable,” Gavin says, scrunching up his forehead like he’s trying to figure out a very hard riddle. “That’s really how he talked.”

I feel like smiling, so I do.

“Did he read you the book?” Gavin says.

“Yes, and I don’t even have to remind him because he remembers by himself and I love when that happens. First he reads a page and then he makes a throat noise that means it’s time for me to turn the page. When the story is over he tells me that he’d love to see a real unicorn one day and I tell him that that’s impossible because unicorns aren’t real and he says, ‘How do you know?’ and I say, ‘People told me,’ and he says, ‘That’s what I hear too, but what if they’re wrong?’ And that keeps me thinking for a while and I’m still wondering if there really is such a thing as a unicorn who lives far away where no people go and it makes me excited to think that maybe I’ll see a unicorn one day.”

Gavin nods like he’s not surprised by what I’m saying.

“But all this happened after dinner,” I say. “I’m jumping ahead.”

I wait for Gavin to ask another question. I notice he’s not like Sydney because he’s wearing socks and his socks have three different color stripes—gray, green, and yellow. I like them and I want to borrow them.

“Hello?” I say, because the quiet is lasting a long time.

“I’m trying to picture his face,” Gavin says with his eyes closed. “It’s hard.”

“Do you want me to draw it?”

He opens his eyes. “You can do that?”

I turn to a new page in my journal and begin to draw.

“People think I’m pretty good at drawing,” I say, “but it feels like cheating to me since I’m only tracing the memories in my head. John Lennon drew pictures in his journal too.”

Faces always take me the longest, so I stop halfway and ask Gavin, “How does it look so far?”

He sits up and takes my journal and lifts it to his face. He looks at it so long that I start to worry that I’ve drawn the wrong person. Then he places his hand on the page and he touches the side of the drawing’s face and moves a finger over to the ear and he says one word in a low, low voice:

“Sydney.”