15

I don’t see Gavin at all the next day. He never comes upstairs, not even for a snack, and when I go downstairs to check on him, his door is shut and there’s no light glowing underneath. No matter how loudly I strum my guitar, he never opens his door.

Mom comes downstairs at one point and at first I think she’s going to tell me to stop bothering Gavin but instead she asks me how the song is coming. I say, “Fine,” and she says, “Can I hear it?” and I say, “No,” because it’s not ready.

And then Dad comes home for dinner and he also asks about my song and I tell him it’s going great, even though it isn’t. I still haven’t written a song that will hit Dad deep and make him want to raise the volume to Spinal Tap 11 and make me always fresh in his mind.

That was yesterday. Now this morning I hear a knock and Gavin is standing in my doorway and he’s doing his hand signal. His blackbird wings seem flappier today.

He walks into my room and pets my American Girl doll on the head (I don’t play with her anymore but Dorothy is still a member of our family). He looks into my open closet and sees how I line up my Converse from heel to toe, but he probably doesn’t realize I also line them up in the order I first got them:

Gavin sits down on my carpet between my bed and the wall. He looks too big to fit in that spot but there isn’t anywhere else to sit in my room except on the bed with me. He reaches into my crate full of stuffed animals and pulls out Wally, my oldest walrus.

“I’ve had him since I was a baby,” I say. “I can remember when Dad brought him home, but I don’t know the exact date.”

Gavin rubs his thumb on Wally’s coat, which has gotten very rough over the years.

“Did you know there’s a real live walrus on the loose?” I say. “He escaped from SeaWorld in Florida and I’ve been following him online. I wish I could meet him in the ocean and swim with him.”

“That might be dangerous,” Gavin says.

“But it would also be fun. I like to imagine things like that, swimming with a walrus or maybe—”

“Finding a unicorn?”

That’s not what I was going to say, but I smile anyway because it’s a good answer and it shows me that he was paying attention when I told him my memories of Sydney. Gavin looks down at Wally again and then he puts him back into the crate.

I have to ask. “Where were you yesterday?”

“Sleeping, mostly. Trying to.” He scratches his fuzzy cheeks. “To be honest, I wasn’t sure if I wanted to hear any more about Sydney. I wasn’t sure if it was doing me any good. I’m still not sure.”

I’m afraid of what might be happening right now. “Are you quitting?”

“No,” Gavin says, his voice changing to something higher. “No, I’m not quitting. I still want to help you with your song.”

I take a deep breath.

“And I still want to know whatever you can tell me about Sydney.” Now Gavin is the one taking the deep breath. “For better or worse, I have to know.” He leans back against the wall. “I think we were up to 2010.”

He’s right, so that’s where I start.

“May twenty-first is a Friday,” I say, making myself comfortable on the bed. “After school Mom drops me off at a guitar lesson that’s supposed to be free this one time. If you come back another time you have to pay, but Mom never takes me back another time because my teacher isn’t as good as Dad. After my lesson Mom picks me up and Sydney is with her and they have coffee cups in their hands that say modcup on the front. We start walking down Palisade Avenue. Sydney says, ‘You’ve gotten taller, Miss Joan,’ and I don’t know if that’s true or not because I never measure my height and I can’t see myself grow. I try to see what’s different about him but it looks like maybe he’s exactly the same, except for one thing.”

“What thing?” Gavin asks.

“He’s wearing a new bracelet. The same bracelet that’s on your wrist now.”

Gavin touches the bracelet to make sure it’s still there. “We both had them and then Syd lost his.”

I’m ready to tell him more about the memory from 2010 but he isn’t finished talking.

“We took a trip to Mexico. After dinner one night we were walking and we stopped at a street vendor. This woman was selling these leather bracelets with little animal shapes carved into them. They were really ugly. I made a joke that we should wear them to keep other people away. Syd never wore jewelry. He hated the feeling of having any extra weight on him. He wouldn’t even keep his phone in his pocket. But he said he’d wear the bracelet for me. One bracelet had a fox and the other one had an eagle.”

With his head leaning back against the wall and his eyes closed, Gavin looks like he might be sleeping, but his mouth is moving just enough to let the words out.

“The woman who sold us the bracelets had a story. She said the eagle was a golden eagle and that it was strong enough to drag a goat off a cliff. She gave me the golden eagle and she handed Syd the fox. She told him to be careful around me.”

“And then the fox disappeared?”

“Yes.”

“That’s spooky,” I say. “What happened to it?”

“He must’ve left it somewhere, I don’t know. He’d always take it off. I was bummed when he lost it, not because I cared about the bracelet, just because I liked the idea of him having to wear it. It made him a little less perfect, less in control.”

“So how did he end up with your bracelet?”

“He joked that he was going to hire a detective to go down to Mexico and find the lady who sold us the bracelets and buy a new one. But instead, he took the eagle bracelet from me and swore he’d never take it off. He wore it in the shower, to the gym; he slept with it. It started to have this funky smell. I told him he was off the hook, he’d passed the test, but he refused to take it off. And the thing is, he really hated this bracelet. I mean, he loathed it. When people asked him about it—and they did—he’d tell them how much he despised it. He’d play it up, how hideous it was, how much it pained him to have to endure it. He did that so they would know, and I would know.”

“Know what?”

He swallows hard. “How much he loved me.” His lips tighten and his head shakes back and forth. “To think I almost tossed it in the fire.”

I understand why he’d want to throw the eagle bracelet into the fire because that bracelet is one hundred percent bad luck and also it’s confusing to have an eagle on his wrist when he’s supposed to be a blackbird. But the rest of it I don’t understand. “Why did you want to burn Sydney’s things?”

“Because it’s too painful to remember.”

I know this so well and it makes me feel so close to him, like maybe we’re more than just songwriting partners, like we’re on the same team in some other way. But I still don’t understand. “Then why are you here now? Why are you talking to me?”

“Because it’s even more painful to forget.”

I never heard anyone say that before. I don’t really know what it’s like to lose a memory, but I guess it’s true that I’ve seen people get pretty upset about it, like when Dad can’t remember the name of an old club that one of his bands performed at or when he forgets the name of another kid’s dad even though they’ve talked before at the park. I also saw it with Grandma.

“My grandma Joan started forgetting before she died. There was this sad look on her face all the time. She was always arguing with Dad and Grandpa. It was like she was trying to tell them something but she couldn’t think of the right way to say it and she felt like no one could understand her.”

Gavin lifts his knees and hugs them. “You think about your grandmother a lot, don’t you.”

“Yes, every time I see old hands on a piano or the baby blankets with the holes in them or when someone says rascal. And whenever I go to Grandpa’s house and the front door opens, I still think Grandma Joan is going to be standing there with her arms open, ready to give me a big hug, but it never happens.”

Gavin rests his chin on his knee. “I know what you mean. I’m reminded of Sydney everywhere I look. When there’s a napkin folded into a rectangle, I always want to refold it into a triangle. That’s what he would do. Or when I’m at a restaurant and they have Tabasco sauce at the table. Usually it’s the brand that says Avery Island on it and Syd used to have a friend named Avery. Every time we saw that bottle of Tabasco sauce, I’d tease him and say, ‘Look who’s here.’ I still say it to myself now.”

Gavin shuts his eyes for a few seconds and then lifts his chin off his knee and says, “Should we keep going?”

Friday, May 21, 2010: Sydney says he has to catch a train back to the city but first he takes me out for ice cream. He and Mom don’t order anything because they have their coffees and Sydney is asking me about my lesson and I tell him it was boring because I already knew what the man was trying to teach me. Sydney asks how I’m liking my chocolate ice cream and I say it’s very good. He wants to know if I can guess his favorite flavor and I say that it’s mint chocolate chip. He asks me how I know that and I tell him I took a guess because I remembered from the time he visited in 2008 that his favorite macaron was the mint one and I also remember he was chewing mint gum when he visited in 2009. And then he asks me all types of questions about those other times he visited, like what day I met him in 2008 and what the weather was and what he was wearing and I tell him it was a Monday in October and the weather was chilly and he was wearing a peach shirt and shoes with no laces and he says, “That is amazing. You are amazing.”

And I say, “Thank you.”

And he says, “I’m more of a future guy.”

And I say, “What’s that?”

And he says, “I like to focus on what’s going to happen tomorrow. And the next day. I’m interested in where everything is leading. I’d rather just leave the past behind.”

I tell the entire memory to Gavin, including the end when Mom and I walk Sydney to the train station. Sydney pretends that my high five broke his hand and Mom hugs him and she kisses him, and when I finish my story Gavin keeps quiet for a long while.

“Syd would get frustrated with me about that,” he says. “If I didn’t get a role, I’d be in a bad mood for days. But if his team didn’t win an ad campaign, he’d just move on to the next one.” Gavin rubs his eye like he’s just waking up from a nap. “Anyway, it’s not a bad song lyric.”

“What is?”

“Leave the past behind.”

“That just came to you?”

He sits up. “Well, Sydney’s the one who said it. But you’re the one who remembered it.”

I’m strumming the Gibson and Gavin is walking around my tiny room. He’s holding a piece of paper that he ripped out of my journal, which is not something I like to do but Gavin says it’s not just about waiting around for an idea to come, it’s also about knowing when the idea has finally arrived.

My arm is getting tired of strumming but Gavin wants me to keep going a little while longer. We have different ideas about what a little while means because he’s been humming and scribbling forever and I guess for him it’s like when you’re dreaming and you think only a minute has gone by but you actually slept through the whole night.

“Okay,” he says at last and his eyes are bright and colorful like glass on the walls of a church. “What about something like this for the chorus?”

He sings along to my chords:

Keep running but I get nowhere

Keep swinging but I hit thin air

I hear you whisper in the back of my mind:

Start over, leave the past behind

Keep dwelling on what went wrong

Keep reaching for what is gone

I hear you whisper in the back of my mind:

Start over, leave the past behind

He stops singing and I stop playing and I feel ticklish all over. This is it, what we’ve been waiting for. I see something, the way he’s waiting silently, something I haven’t seen before but I know it so well because it matches how I feel inside: he wants so badly for me to love his words because he loves them.

“It’s about Sydney,” I say.

He gets a little shy. “It doesn’t have to be.”

But I don’t mind because I can’t always think of interesting things to write about and besides, the lyrics were already about Sydney even when I was writing them. I think it’s good to write a song about someone who isn’t around anymore, like John Lennon did for his mother in his song “Julia.” And I’m missing Sydney too after spending so much time with him in my memories, almost as much time as I’ve been spending with Gavin, so I think it feels right.

“I guess I got in a flow,” Gavin says. “I’m sorry. I know it’s your song.”

“No. It’s our song.”

I’m not even sure anymore which parts are mine and which parts are Gavin’s and that’s how it was with John Lennon and Paul McCartney when they wrote together in the Beatles. Dad says you can’t tell where one of them ends and the other one begins because they were like one super-person instead of two regular people. Maybe that’s why I like the songs they wrote together better than anything John ever wrote alone.

“You should finish the lyrics,” I say, “and I’ll take care of the music and it’ll be half and half. I’ll play the instruments and you sing.”

He slides his hand through his hair either because he has great style or because he has a headache, I’m not sure which.

“The words are coming right out of you,” I say. “It’s magic. You already have the chorus. That’s the most important part. Now just write the verses.”

He gives me a long look. “If that’s what you want.”

But he doesn’t mean it like that, I can tell, because I say the same thing to Dad when he and I split up chores and Dad takes vacuuming and I take organizing and I pretend that I don’t mind if we switch jobs but really I’m so happy I got organizing because that’s something that makes total sense to me. So I’m thinking now that maybe Gavin wants to write this song just as much as I do.

And if people remember the name Joan Lennon because I teamed up with Gavin Winters, then I guess it’s the same as someone watching Gavin’s show because he started a fire in his backyard. I don’t care why they remember me as long as they remember me, because I never want to feel the way I did when Grandma Joan forgot me. I just want to feel safe.

“One more thing,” I say. “When we send our song into the contest, my name goes first. Joan and then Gavin. Deal?”

He shakes my hand. “I can live with that.”

I open the fridge and look around until something excites me. I open the pickle jar and find the greenest one and I wrap it in a napkin because Mom hates when I drip pickle juice on the floor.

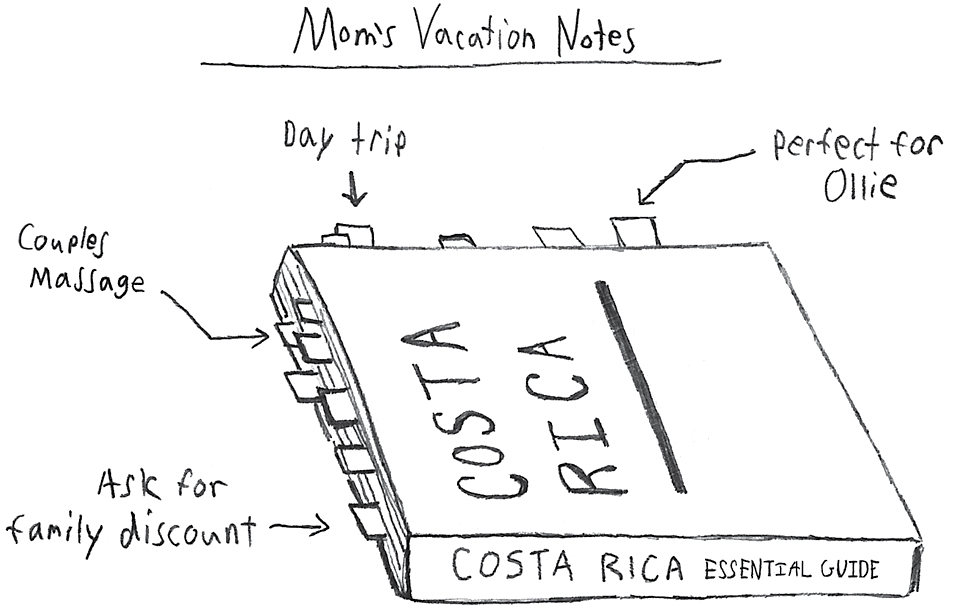

Mom’s book is on the kitchen table. It looks like one of her schoolbooks because it has her yellow notes sticking out of the top, but it’s something else:

Seeing Dad’s name messes up the good mood I was in. Dinner is the only time I see Dad lately, and that makes me want to take Mom’s book and slide it through our paper shredder.

The phone starts ringing and I just want to shut it up so I answer it. “Hello?”

“Hello,” a man says. “Is this Mrs. Sully?”

I decide to say yes.

“Oh, good afternoon, Mrs. Sully. I’m sorry to bother you. My name is Robert Brickenmeyer. I’m the head neurologist at the Hollybrook Cognitive Research Center here in Summit. We’re one of the area’s premier research centers for Alzheimer’s. As you might have guessed, I’m calling in regard to your daughter, Joan Sully.”

“I’m Joan Sully,” I announce.

I can’t say another word because Mom comes in from the bedroom and takes the phone and hangs up. Her hair is in a ponytail and her skin is pink and she’s wearing her black leggings and her bouncy sneakers. She used to belong to a gym but she stopped going because they wouldn’t give her a good deal. Now she just exercises at home and she hates that Dad doesn’t exercise but still stays skinny. She says that isn’t fair.

I follow her down the hall to her bedroom. “It was for me.”

“I’m sure it was,” Mom says.

“Why can’t I talk to them?”

The lady on the television is frozen and Mom is about to unfreeze her with the remote but first she needs a few more seconds to catch her breath. She answers me in a quiet voice, which is her favorite move when I get loud. “Do you want to?”

I wasn’t expecting that.

“Maybe we should set up a meeting,” Mom says, shrugging. “They might finally stop calling. If it’s something you really want to do, I have a whole list of people who are itching to talk to you.”

“That man said something about old-timer’s disease. That’s what Grandma Joan had.” I know it’s called Alzheimer’s but Dad calls it old-timer’s instead because he says it helps to make jokes when life gets too sad.

“Yes,” Mom says. “That’s what your grandmother had.”

I wish I had met Dr. M before Grandma Joan started forgetting because maybe he could have figured out how to capture all her memories and put them inside my brain so I could keep them safe.

“Maybe this Dr. Robert guy thinks I can help old people remember,” I say. “Wouldn’t that be great?”

She takes a long look at me. “Tell you what—write down the man’s name and I’ll give him a call.” Mom pulls her ponytail tighter and gets back to her video. “By the way, I heard you and Gavin playing in your room today. The song sounds like it’s really coming along.”

I leave her bouncing in her bedroom and my legs take me slowly down the hall. The sun is shining through the blinds but it looks cloudy to me. I love thinking about my grandmother but I also hate it, because what happened at the end of her life makes all the other memories I have of her feel less special. It’s like we were playing this great concert together and when we got to our last song of the night, she just left the stage and now I have to face the crowd by myself and sometimes I just don’t feel strong enough to do it alone.

But I can’t quit now, not when Gavin and me are finally getting somewhere with our song. Mom even said so.