29

The next morning Gavin finally comes upstairs. Mom is leaving for her tutoring session and Gavin asks her when she’ll be home because he really needs to chat.

Mom leaves and Gavin makes coffee. He offers to make me breakfast but I say no and then he offers to squeeze me fresh OJ with the present we got Dad for Father’s Day last year and I say yes because I’m afraid that if I say no to every single thing, he’ll know there’s something fishy going on. But the OJ is a mistake because it makes my stomach feel extra-nervous.

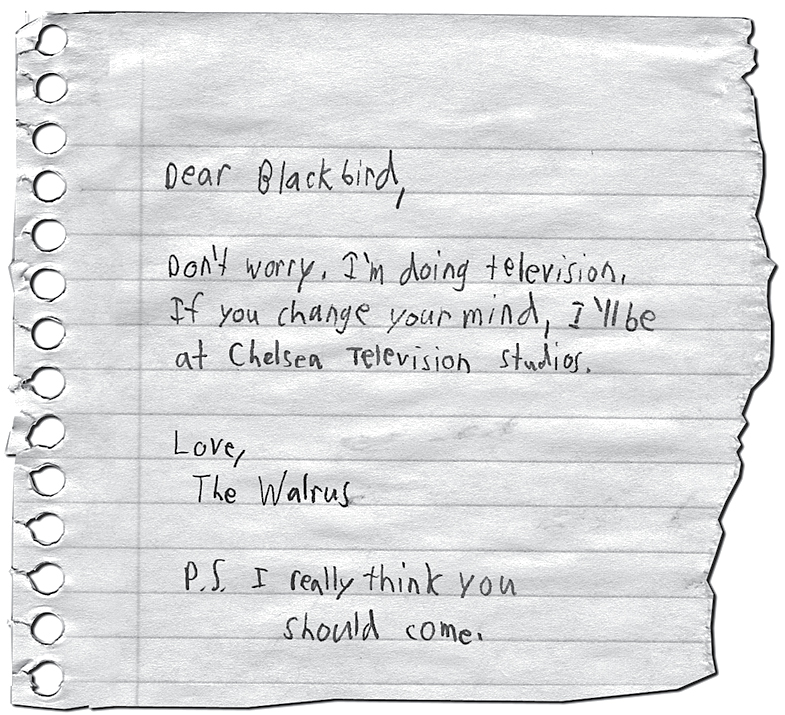

And then my stomach feels even more nervous when Gavin asks me why I’m wearing a dress. I tell him I’m going to make a video on my iPod in my bedroom and he believes me. He finishes his coffee and says he has to use the bathroom. He goes downstairs and that’s when I pull the note out of my pocket and leave it on the kitchen table:

Finally my memory is good for something. I go the same way Gavin and I did the day we went into the city, down the big hill and through Hoboken. It gets trickier when I reach the underground train because Gavin used a yellow card to get us through the gate but I don’t have a yellow card. I thought of everything else. On my back I have Dad’s Gibson and inside its soft case I have all my supplies: my journal, change purse, the Sydney guitar picks, bubble gum, and the papers that Felicia sent over. But no yellow card.

A nice man in a Mets jersey sees me standing by the gate and asks me where I’m going. He slides his yellow card into the gate and tells me to walk through. He makes sure I get on the right train and I thank him for his help. I know I’m not supposed to talk to strangers, but I’m not supposed to do a lot of things.

The train lets us out underground. I walk past a man on a bench who’s bent over so far it looks like he might fall onto the tracks, but I don’t have time to help him. It smells like the toilets at the Riverview Fair and I have to follow the people up the stairs until it’s bright and I can finally breathe.

There are so many people and they’re knocking into my guitar like they can’t even see me. Suddenly I realize where I am: I’m in New York City and I’m all alone.

This place is very dangerous because it’s hard to tell who’s crazy and who’s normal and that’s what happened to John Lennon. Mark David Chapman looked like a nice guy, but he was really a fanatic (which is totally different than just a really big fan, like me and Dad). Mark David went to the Dakota and he walked right up to John and he shot him with a gun, even though earlier that same day John gave Mark David his autograph. I don’t know why Mark David did that because John was being so nice to him. It makes me think of that photo Gavin took with those two women (Tuesday, July 16, 2013). Dad says Mark David wanted to be famous by hurting someone famous and so for just this one time, I’m happy to be nobody special.

But not for long, because today I’m going to be on television.

I walk to the corner and reach my hand up as far as it can go, but the taxis just zoom by. I wave and wave and the guitar is getting heavy on my back and the shoulder straps are digging into my skin.

I’m still waving my arm when I hear a man’s voice behind me: “Just you?”

The man has a mustache, but it’s not bushy like a cowboy’s, it’s thin and neat. He sticks his arm way up high and a taxi stops. The mustache man puts me in the backseat and I tell him I want to go to Chelsea Television Studios. He tells the driver where I want to go and I ask the mustache man, “Do you watch The Mindy Love Show?”

“Never heard of it.”

“Well, I’m going to play a song on the show. You should watch.”

He says, “Good luck,” and he taps his hand on the taxi roof, and the driver starts driving. I see the driver’s dark eyes in the mirror and he says, “Hello.”

And I say, “Hello. My name is Joan Lennon.”

I wait for the driver’s eyes to get big because he is amazed by my name, but his eyes stay the same size and he says, “My name is Adisa.”

“Do you like the Beatles?”

“No, no beetles. Where I am from, this is no good.”

“The last time I was in a taxi was July sixteenth, which was a Tuesday.”

“I like Fridays the best. Do you agree?”

“I do like Fridays,” I admit.

The car turns. “We must go all the way to the river,” Adisa says. “I have wondered what this looks like inside, the studios where they make the television programs.”

“Me too.”

“You have never been?” Adisa says.

“No.”

“This is a special day. I will pray for you.”

Sunday, February 20, 2011: Grandpa brings me to church because he says if he doesn’t bring me then no one will, because Dad doesn’t believe and Mom is Jewish. He says we’re here to pray for Grandma Joan, but he never tells me how to pray so I just close my eyes and listen to the lady singing. I like how in church you can sing softly but your voice fills the whole room.

I wish Grandpa could see me on TV today, but he’s busy working and also it’s a secret.

Adisa stops at a red light and he taps a beat on the steering wheel, just like Dad, and I ask Adisa, “Do you play music?”

“I play the djembe,” Adisa says, tapping away. “But only in the car.”

“That’s like my dad.”

Adisa turns his head around and his white teeth glow behind the glass. “Your father drives a taxi?”

“No.”

He turns forward and we start moving again. “What is his job?”

“Well, he used to make music for commercials.”

“What commercials?” Adisa says.

“Have you ever seen the one where the Coke bottle turns into a telescope?”

Adisa turns around, but he’s still driving. “This is your father? I love this commercial! They play it on the TV in Times Square. This is a very nice commercial. Wow, I am very lucky today.”

So am I. I’m glad to have Adisa as my driver because he knows how special Dad’s old job is and it makes me feel even more sure about my secret mission.

Adisa drives fast, the same way Dad always tells me he drove after I fell in Home Depot. I have to hold on to the handle because it feels like we’re going to crash into other cars. Adisa likes to honk the horn and I like to hear it.

Through my window I watch people walk past a man sleeping on the sidewalk. I wonder if the man’s family knows where he is. Maybe he’s sneaking around like me. I think about reaching into my guitar case and throwing the man some coins, but Adisa speeds away before I get a chance. I wonder if the sleeping man drinks coffee like Dad does when he wakes up because Dad says the city has the best coffee.

Tuesday, July 16, 2013: Gavin says New York City has the best pizza.

Now the car isn’t moving and I can see the river out my window.

“We are here, little girl.”

I don’t think Adisa remembers my name, which isn’t very nice. He presses a button and points to a sign with bright red numbers. “Seven forty-seven, if you please.”

I open my change purse and count my coins and Adisa watches me through the glass. He gets out of the car and opens my door. “Okay, this is no problem.” We make a pile for each dollar and Adisa lines up all the piles on the seat. “You saved up this money? This must be a very important day.”

“Yes, it is.”

I have no more coins left in my case. I look at the piles on the seat and there are only six.

“Okay, little one,” Adisa says. “This is very good. Have fun on the TV.”

He holds up my guitar case and I crawl out of the car and Adisa slides the straps onto my shoulders and points to a building along the river. “This is where you go. I wish you good luck.”

I look at the building and the river behind it and I see New Jersey. I wish I could see my house from here because I want to show Adisa where I live and how far I’ve come. But when I turn around, the taxi is gone.