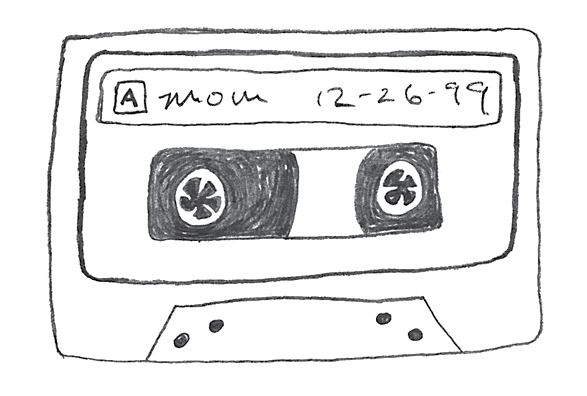

I fit the cassette into Dad’s old Walkman. I rewind the tape and it squeals all the way to the beginning. I press down on the chunky Play button and through the hiss I hear Grandma Joan’s piano and her voice. I shut my eyes and pretend she’s here in my bedroom giving me a concert.

When Grandma lifts her hands off the keys and her foot off the pedal, you can hear her sigh and it’s the kind of sigh you do after a tasty drink or a deep laugh or when you’ve just remembered a great memory.

The recording ends but the tape still plays. I let it hiss and it feels like she’s still here.

“I wish you could hear my song.”

The wheels spin through the plastic window.

“I wish it could go deep into your system.”

Dad says I carry her memory and he’s talking about my name when he says this, not my HSAM.

“I want to win because of you. I’m going to win.”

I listen.

“Hello? Grandma?”

The wheels get slower and the cassette clicks and the hissing stops and the tape runs out.

My door opens. “Ready to go?”

Dad is wearing his lace-up boots and tight jeans and button-down shirt and a black jacket on top to fancy it up. It’s the kind of outfit he used to wear for his meetings in New York before he shut down the studio and before the new lady moved in downstairs. Pam is her name and she’s hardly ever home because she works part of the week in Toronto, which is in a separate country, and she says we can use the courtyard as much as we like. Also, she didn’t make Dad tear down the Quiet Room because she says it’s a good place to keep all her clothes. She swears my initials are still there above the socket.

Dad comes up behind me and sees the tape player. He lifts the ends of my hair and pretends to pull. “Are you going to be okay if you don’t win, kiddo?”

“I don’t want to think about it,” I say.

“Just remember, art is subjective. People like different things.”

“Like how some people like Paul McCartney and some like John Lennon?”

“And some like both.”

“I like Paul McCartney too,” I admit.

“So do I,” Dad says. “I love all the Beatles.”

He kisses the top of my head and walks to the door.

“No matter what happens,” Dad says, “I just want you to know that I’m really proud of you. I hope you’re proud too. You just have to keep making art that feels good to you. You can’t control what happens after that. It seems like no one’s paying attention, but then, when you least expect it, someone hears it. Just keep putting yourself out there. It’s the hardest thing. But you never know. That’s it. You just never know.”

It resonates, which is something guitars do but also words. It resonates because one day this summer I was eating dinner with my family and I was worrying about my own stuff and out of nowhere a stranger asked to shake my hand because she saw me on TV (Saturday, August 17, 2013).

Dad taps his hand on the door, not like a drummer, more like a bee that’s banging against a window, looking for a way out. “I’ll go pull the car up,” he says and leaves.

There are fewer than thirty people in the world with HSAM but right now there are only ten people in the world who can win the Next Great Songwriter Contest and I’m one of them. That means I’m even more special at music than I am at remembering. (Some of the finalists are more than one person, but there’s only one award given out, so that’s why my math works. Mom would be proud.)

Dad hates when a person says to be honest because it means that the person was just lying or is about to lie but I want to say it anyway. To be honest, I didn’t think I’d actually make it to the finals because usually when I want something really badly it doesn’t happen, like when I want to turn the TV off just by blinking my eyes or when I want a three-legged dog to grow back his missing leg.

To be even more honest, I thought my music days might be over too because wanting something so badly is tiring and it makes me do things I shouldn’t do, like sneak off to the city by myself. And to be really, really honest, I haven’t been thinking too much about the contest over the last two and a half months. I’ve been busy with other stuff like Dad taking us to Six Flags and Grandpa taking me to the music store to buy a new guitar and Mom taking me to the dentist and also to swim at Harper’s house and also to shop for school supplies. And then I started school and I wrote new songs that are even better than my old ones and I watched the walrus swim up and down the coast until they finally caught him all the way up in Nova Scotia, Canada.

That’s why when Dad got the e-mail inviting me to the ceremony in New York City on Friday, October 25, which is today, I was surprised. Now that the contest is on my mind again, I know I have to win, no matter what Dad tries to tell me. He’s been so great to me these last few weeks but I still worry about my memory not being safe with him or Mom or anyone else. I can be the busiest girl in the world but I’ll never forget my dream to one day be important enough to be remembered. Not just today but always.

I get up off the floor and straighten out my dress and take a look at myself in my long mirror: navy and red dress, sparkle Converse, glitter barrette. That stuff is there, but not really, because my mind is somewhere else. My mind is always somewhere else but I finally found the look to match how I feel.

Or maybe I always knew how to do the rock-star look. Maybe it’s the kind of thing you can’t watch yourself do in a mirror, just like you can never see what you really look like in sunglasses, because it’s something only other people can see for you.

Dad says we’re here, but this can’t be the right place because there’s no red carpet or reporters or cameras and there’s no sign outside announcing the contest. It’s just a fat doorman with a clipboard.

Dad gives the doorman outside the club our names and he angrily checks his list. The doorman draws a big X on my hand and I hurry through just in case he tries to eat me.

We push past the crowded front bar. I can hardly hear Dad tell his story about performing in this same venue with one of his bands because the room is so loud. Also I’m thinking about how long it took to get here, how I first had to meet my partner, write our song, make the finals, sit in traffic through the Holland Tunnel, walk through what Dad called the East Village, and finally step into this tiny back room which does not look like a giant theater with stadium seats and a red curtain but more like a dark cave with folding chairs and a ceiling that comes down on you and makes you want to bend over so you don’t get crushed. There’s no one else here except the long-haired man sitting behind the sound booth and he’s too busy looking at his phone to say hello to us.

“We’re in the wrong place,” I say.

“Nope.” Dad points to a piece of paper taped to the first row of chairs that says Reserved for Finalists. He sits with me so I’m not alone and Mom takes a seat in the area behind us.

Cold air blows down from a spot in the ceiling and I hug myself to stay warm. This may be the loneliest place I’ve ever been to except maybe the Turtle Back Zoo where each of the reptiles is kept all alone in its own glowing hole in the wall.

The doors to the front room open and finally the people start coming in. They sit in chairs and stand up in the back of the room. The front row starts to fill up, but the other finalists don’t look anything like me. Maybe I should feel happy that I’m the youngest one here but I don’t like it because I’m always the youngest, even with HSAM, and this time I just want to be like all the others. I want everyone to know how serious and important I am.

Dad is chatting my ear off. “Remember what I told you. Some of these people have been doing this a long time. There are plenty of other contests you can enter. You have your whole life ahead of you. I love you. You know that, right?”

“Yes, Dad.”

I look around some more and stretch my neck high. It looks like all the people are here now. No one else is coming through the back door.

So far this contest is nothing like I pictured. My metal chair is ice-cold and the soundman is playing the worst music and I don’t even see programs anywhere. When you go to a play or a wedding they normally give you a program so you know exactly what’s going to happen and when it’s going to happen, but there’s nothing under my chair except dust and a flattened cigarette. I don’t understand why they’d want to announce the next great songwriter in a place like this. I’m worried that I made a big mistake thinking this contest could help spread my song around the world. I’m learning that it’s a mistake to trust just about anyone because they’ll say things to get you excited and then they’ll forget what they said and just do something else. I want to slide onto the dirty floor and crawl on my knees under all the chairs and go past the hungry doorman and call a taxi, maybe even Adisa’s taxi, and have him drive me home to Jersey City because this isn’t how it was supposed to happen.

“Pardon me, love.”

I sit up straight, and it’s the only fake British person I know. His face is smooth and his hair is longer and his dimple is bumpy and his palms are flapping like wings.

I do my hand signal back to him.

“Thanks for saving my seat,” Gavin says to Dad. Dad says something back but I’m too busy staring at Gavin. If this ends up being the last time I ever see him, I want to make sure I notice all of him, like how the cuffs of his jacket are unbuttoned and the bottoms of his jeans are rolled high and the buckle on his belt looks rusty and his beer bottle is curled in his left hand and it says BROOKLYN on the label and his right arm is hanging down and his right wrist is naked where Sydney’s bracelet used to be.

Before I ever met Gavin Winters, I heard a lot about him from my parents and from Sydney and from TV and then I got to know him in my own way. Then he disappeared but I was still hearing about him from my parents and from TV and so he was never really gone, even when he was. It’s hard to know if he’s really here right now or if it’s just a memory or something else. I touch his hand and he looks down while he’s listening to Dad and he squeezes my hand and I’m not even mad anymore because he promised he’d be here and here he is and I know it’s true because I can feel him.

Dad looks at his watch. “It’s almost time.” He bends over and chokes me with a strong hug. He pats Gavin on the shoulder and walks back to where Mom is sitting.

Gavin takes Dad’s seat. “How are you feeling?”

“Fine.”

“You don’t look fine,” he says, ruffling up my hair.

“Stop.”

“Relax, the messier the better. It shows you don’t care.”

“But I do care.”

His dimple fades a little as he sips his beer. I’d feel a lot less nervous if I had my guitar with me, but Dad says it’s not that kind of event. Not all the finalists are performers, they’re writers, so instead of a guitar, he told me to bring a speech just in case I win.

I reach into my dress pocket and feel the folded piece of paper inside my palm. Mom helped me with the words. I take it out and read it again for practice. Behind me, Mom smiles big and I smile back at her but my smile is only small.

When I face forward again there are two women onstage. The one woman looks like a grown-up Orphan Annie and the other has long white hair that’s folded on top of her head in layers, like a wedding cake. My chair starts vibrating like it did when we had an earthquake in Jersey City on Tuesday, August 23, 2011, and I grip my chair because I’m afraid the floor will open up and the ceiling will collapse and I’ll be crushed and I’ll never know who won the contest. But it’s not an earthquake. It’s just my knees.

Annie lifts her chin up to reach the tall microphone. “Hello.” She waits for the room to quiet down. “Welcome to the award ceremony for the first-ever Next Great Songwriter Contest.”

Annie pauses so people can cheer and clap, and most of us do.

“As some of you know, Coral and I have a blog and the gist of the blog is that we disagree about pretty much everything and that leads to what we hope are interesting discussions about music and art and culture and whatever. But one thing we actually agree on is that there is far too much attention paid today to the singers of the world and hardly any consideration goes to the songwriters. We’re big fans of stories and storytellers. And we’re also big fans of our respective home states, New York and New Jersey. We’ve always known that there was a lot of talent hiding right here in our backyards. We wanted to see if we could find some of you and help get your names out there.”

I look over at Gavin and he looks at me. His face says We got this but I’m not sure. We both turn back to the stage.

The woman with the wedding-cake hair takes over the microphone. “We were shocked by the amount of entries that came in. We had a really difficult time narrowing it down to just ten, but we did our best and here we are. In the front row are our ten finalists. Let’s hear it for them.”

I’m ready to take a bow, but no one else is standing up, so I stay in my seat.

“Each of our finalists will receive a prize pack from our generous sponsors that includes gift certificates, music distribution, and a magazine subscription. So that kicks ass.”

I didn’t realize there’d be prizes for the losers. That does kick ass.

“And our first-place winner will get his or her song featured on our blog and it will also stream on some of our partner sites. Plus, he or she will get a check for five thousand dollars, thanks to Zeem Music.”

It’s too late to use the prize money to save Dad’s studio but I wonder if five thousand dollars is enough to take a trip to Los Angeles because Gavin said it’s the capital of entertainment and that sounds like the perfect kind of place for me.

Annie bends the mike back to her. “I know we’re here to find out who will take home the grand prize. But before we get to that, we have a few things to get out of the way first.”

A pointy man in a suit walks onstage and he thanks a long list of people and then Annie comes back. She invites someone else onto the stage, someone she calls a great artist who’s been “featured a ton” on their website, but this guy does not look great to me. He’s bald and he’s got a big belly that pushes his acoustic guitar far away from his body. He has to reach his arms out to play it and his voice sounds like a sick bird. I’m not impressed. This is not a rock star.

The worst part is that I don’t know his song. If he’s so great and his music was on the contest website, then I should know it and everyone else should too.

The man finally finishes his boring song and Annie helps him off the stage. I’m not sure why he can’t get down on his own.

“Let’s hear it one more time for the great Bisk Weatherby.”

I’m clapping, which scares me because I don’t mean to be clapping. I’m just trying to be nice. What if that’s all clapping is? A big lie to be nice? Gavin is clapping too.

Annie calls another musician to the stage and this guy looks much cooler. He’s a singer-songwriter that everyone seems to know, but I barely hear him because there’s already too much happening in my brain and also my body. I really have to pee.

The singer-songwriter finishes his song and the women come back to the microphone. “So we’re going to move things along now,” Annie says. “When I announce our third-place winner and runner-up, please stand up and take a bow.”

So we are bowing. That’s more like it. I just hope my legs work.

Annie looks down at an index card and I grab Gavin’s hand.

“Without further ado,” Annie says. “Third place goes to Olsen T. DeLawrence for his song ‘Quiver.’”

Olsen is a goofy guy with glasses and when he stands up he almost hits his head on the low ceiling. My heart is pecking like a woodpecker. I tell Gavin, “I really have to pee.”

“I think it’s a little late for that.”

“I have to go.”

“You’re going to miss it,” Gavin says.

“I don’t care.”

“Just hold it.”

“You can.”

And then Annie calls out the second-place winner. She says two names.

“Gibson and Ren,” Annie says. “They wrote a heartbreaking song called ‘Third Chance’ that I swear I cannot listen to without bursting into tears. I’ve tried. It’s impossible.”

A crying song. I told Gavin we needed a crying song but he wouldn’t listen to me. He told me to forget about the crying song, which was bad advice because crying is all about remembering and that’s what girls like to do and sometimes dads too, like when they’re driving home from seeing their moms.

But it’s not over yet. We’re so close. Just one more winner left. It can happen. It can really happen. Come on, Annie, just say my name.

Annie clears her throat and I drop my head down to my knees. “And now, the moment we’ve all been waiting for.”

Dad holds my hand past the hostess and past the people talking loudly at tables and past the waiters balancing trays, all the way to a glass door that I can’t see through because of the white curtain.

“I’m not hungry,” I say.

“You don’t have to eat,” Dad says.

“Where is everybody?”

For the first time in my life, I don’t remember a single thing that happened. Actually, I remember exactly two things, and the first thing is the name of the girl who won because a name like Victory is so strange and unfair. The second thing I remember is that Annie and the wedding-cake-hair woman took a picture with all the finalists and then everybody wanted to take separate pictures with just Gavin and they couldn’t believe he was a part of their stupid contest. I can’t remember if Victory was pretty or ugly but she was probably very pretty, and I can’t remember if the check for five thousand dollars was one of those giant checks or the kind that fits into your pocket, and I can’t remember what Gavin said into my ear when we lost, and I can’t remember how we walked out of that back room, or how we got outside, or what Dad was trying to tell me as he carried me down the street and into this crappy restaurant. So this is what it’s like to have a normal brain. I think I hate it.

“You’ll see,” Dad says.

I’ll see what? I don’t even remember what we were just talking about.

The door opens and there’s Mom and Grandpa and my uncle and my two aunts and Gavin. I don’t know the rest of the people: an older woman with short boy hair and big hoop earrings, a serious-looking man with a button-down shirt and sweater, and a lady with blond hair and a nice tan.

Gavin grabs a big plastic bag that’s leaning against the wall. He reaches for me with his other hand and tells the group, “We’ll be right back.”

We walk outside into the busy night and stand against the building.

“What place do you think we came in?” I ask.

“It doesn’t matter.”

“Yes, it does. There’s a big difference between tenth and fourth.”

“It’s just an opinion.”

“But tenth is last place,” I say.

“Who cares?” Gavin says. “Think about the thousands of people who entered. Look how far you got.”

The city people walk around us with smelly cigarettes in their hands and interesting clothes on their bodies and wires sticking out of their ears.

“I only got here because you helped me,” I say.

“So what? Everyone gets help somehow.”

“It doesn’t matter, does it? No one cares. No one even remembers his name.”

“Whose name?” Gavin says.

“The guy who came onto the stage and played his song. They said he was so great but no one knew his name or his music and no one knows Dad or me, and no one will remember us, and it’s just so sad and I can’t even think about it anymore.”

I heard on the news that when there’s an avalanche the snow gets as hard as concrete and that’s how it feels right now, like there’s concrete all around me, because there’s nowhere else to go. I’m out of ideas.

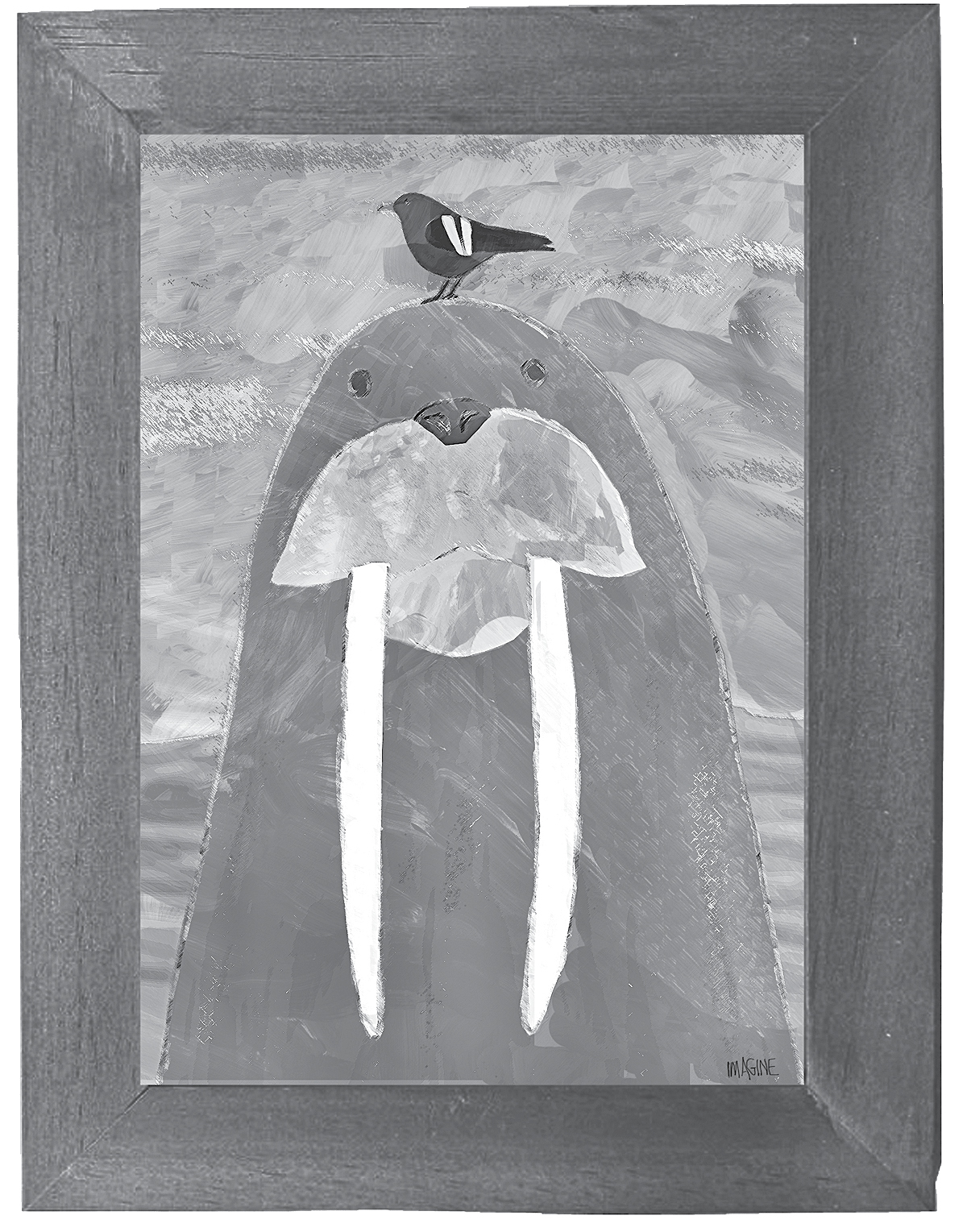

“Let me show you something.”

Gavin reaches into his big plastic bag with both hands and slides out one of those foldable wooden TV trays. He shakes the plastic off the tray and turns it over and it’s not a TV tray after all.

“This is for you,” Gavin says.

“My friend is a painter,” Gavin says. “Actually, she was Sydney’s friend. I visited her yesterday and told her exactly what I wanted.”

“What’s on the bird’s wing?” I ask.

“A bandage.”

“He’s hurt?”

“Yes. But he’s getting better. And see here in the corner?”

He holds the painting up to the street lamp. I push my face close and see a word in all capital letters: IMAGINE.

I feel a chill. The night isn’t cold, but I feel a chill.

“You and Sydney have that in common,” Gavin says. “You believe.”

He’s glowing under the street lamp and I wish I had a camera so I could take a picture of him. I’d have Dad turn the picture into a poster and I’d put the poster on my wall and I’d stare at it every night before falling asleep. But it’s okay that I don’t because I have my own built-in camera.

“Thank you,” I say.

“No. Thank you.”

He scratches his forehead and makes small shapes with his mouth. When I’m nervous, I bite the insides of my cheeks. “You know, I’ve always wondered,” he says. “Do you really like John Lennon’s music that much? Or is it just because your dad loves him?”

I think about it. It’s hard to figure out. “I like that we have our own special thing.”

Gavin smiles. “I like it too.”

It looks like he’s ready to go back inside the restaurant but I’m not in a party mood and I don’t want to share Gavin with all those people because he’s my partner and it took me so long to get him back.

“We should write more songs together,” I say.

“We should.”

“We can call ourselves the Reminders.”

“I like that,” Gavin says. “It’s a good name.”

“We just need one song. That’s all it takes. One song that the whole world never forgets.”

He looks at me for what feels like a very long time and then he says, “I heard ‘God’ the other day. We were talking about that song the first day I heard your music. We were talking about magic.”

I love when people remember.

“Do you know what John is saying in that song?” Gavin says.

I don’t.

“He’s saying he was the walrus, but not anymore. Now he’s John. Now he’s himself. Everybody builds these people up to be bigger than they are. Elvis, the Beatles, Zimmerman. Do you know who Zimmerman is? That’s Bob Dylan. It’s a myth. I named myself Winters, but I’m a Deifendorf. That’s my family. And that’s what John is saying. He’s talking about family. He’s saying that all that really matters is him and Yoko.” He points at the restaurant. “Those people waiting in there, they’re the ones that matter. No one else.”

He won’t stop staring and I try to smile but it won’t stop the tears. “I don’t want to say good-bye to you.”

He pulls me in and into my ear he makes a promise and everything is upside down but it feels right this way because it’s kind of like a dance song and a crying song wrapped into one.

In the middle of dinner, Gavin taps his knife against a water glass. This happens after Grandpa lifts me into the air with his strong hands and tells me he’s going to throw me across the room unless I give him my autograph. The problem is that getting thrown across the room actually sounds like fun, so it’s a hard choice to make.

It’s after Gavin brings me over to the serious-looking man who Gavin calls his agent and says, “Carl, I’d like to introduce you to your newest client.” Carl tells me that he’s heard all about me and he says I’m very photogenic, which sounds like a disease but it’s the opposite.

And it’s after Gavin takes me to meet the lady with the boy hair who’s actually his mom. She hands me a bouquet of flowers from her garden and she explains in a very excited way that these flowers are “completely chemical-free” and she also tells me that when she looks at me she feels the same way she did about Gavin when he was little. I ask her what that means and she says, “You have that star quality,” and Gavin rolls his eyes but I think it’s a very nice thing to say.

And it’s after Gavin walks me over to the last stranger in the room, the one with the same light blue eyes he has, and I go to shake her hand but she gives me a high five instead and tells me she adores my outfit. Her name is Veronica and she’s a daughter and a sister and she’s also going to be a mother soon, but in a way that doesn’t make your belly get fat. Gavin already knows that the baby will be named after the father because it’s a name that works for a boy and a girl and I hope even though we’ll be ten years apart that baby Sydney and I can still be friends.

And it’s after Mom and Dad stare at each other with anniversary looks on their faces, and Dad, who will always be my favorite musician, lays his head on Mom’s shoulder in a way that looks familiar, something about how moms make us feel, because Mom makes me feel the same way at the table when she puts her arms around me and tells me how proud she is of me.

It’s after all this that Gavin starts tapping his water glass and everyone stops talking. Dad reaches under the table and opens a case. He takes out his Gibson guitar and hands it to me. I’m not sure what to do with it.

“Play it,” Gavin says.

I’m not in the mood but I want to make a good impression in front of Gavin’s agent so I hang the strap over my shoulder and I play the first thing that comes to my mind, which is “Look at Me” by John Lennon.

“Not that,” Dad says. “Your song.”

I stop for a drink of water and take a deep breath and make a G chord. I don’t have Sydney’s guitar picks with me so I use my fingers, just like Dad taught me. I look down at the strings and I feel them shake beneath my hand.

Someone in the audience is squeaking his chair and it’s Grandpa. He taps Gavin’s mom on the shoulder and takes her by the hand. They move into the corner of the little room and he twirls her and dips her and she laughs.

I try to hold on until Gavin starts singing, and he does, his voice making my heart beat even faster. We’re really going now and everyone is here, so many eyes, the ones that matter, singing and smiling and dancing and crying. I’m not sure about tomorrow, tomorrow never knows, says John, but they’re looking at me now, all of them, like they really see who I am. I want to stay with them forever and I guess there is a way. I’ll save them in my box. I’ll keep them safe always. It’s what I do. I remember.