5

• • • • • • •

The Enigma of Precision Engineering

The next issues we have to face when analyzing the technology required to build the Great Pyramid are

- The precision-leveled base

- The precise orientation to true north and the alignment with the cardinal directions

- The sophisticated architectural design of the interior

- The masterful engineering required to ensure that each of the 204 tiers was as flat as the base, so that the faces and edges of the pyramid would come together at the top to form a perfect apex

The base of the Great Pyramid is massive, covering about thirteen acres. As noted at the end of the last chapter, the engineering firm that analyzed the structure concluded that the base was so level that it would require modern laser technology to duplicate it.

Each side spans the distance of two and a half football fields in length. To say that this was a massive, extraordinarily complex undertaking would be a gross understatement.

Here again, we are given to believe that (a) workmen labored with granitic balls to hack the irregular surface of the limestone bedrock as flat as the bottom of a frying pan over a thirteen-acre area, (b) the surveyors—who were called rope stretchers—could survey a thirteen-acre base to the same accuracy today achieved with laser levels, and (c) they knew how to accurately orient this massive edifice to the cardinal points and true north.

Fig. 5.1. Note the flat, fifty-ton, precision-cut-and-placed granite blocks that frame the King’s Chamber

It is still the most precisely oriented building in the world.

The ancient Egyptian surveyors were called rope stretchers because that was the extent of their technology. Their architects and engineers would have possessed no more than rudimentary mathematics and very basic algebra.

As we saw, the modern Japanese team, who failed to reproduce a scale model (even one that lacked the complex interior spaces), found that they could not meet the many engineering challenges posed, even on a very small scale.

Perhaps if the obelisk team had succeeded at each stage of the process, we might be persuaded to consider the possibility that some kind of ramp system could have been used to build the Great Pyramid. However, if Egyptologists cannot duplicate the quarrying, lifting, transporting, and raising of a thirty-five-ton obelisk, then they certainly cannot account for the fifty- to seventy-ton blocks of granite that enclose the King’s Chamber.

Additionally, it has never been shown that the types of boats found at the Giza Plateau could be used to transport the blocks from Aswan to the site about five hundred miles up the Nile River.

The ramp debates have been going in circles for generations, and they are, in fact, meaningless. The quarry and transport problems of the largest blocks used in the pyramid’s construction have to be solved first.

There is no point in trying to show how the millions of smaller blocks may have been lifted into place using a ramp system if you cannot first demonstrate that you can solve the greatest challenges. Those occur at the quarry and with the river transport of both the dozens of granite blocks used in the King’s Chamber and the tens of thousands of casing blocks across the Nile.

The feasibility of hoisting the granite blocks out of the quarry, transporting them to the Nile, and then ferrying them down the river to Giza—using primitive tools and methods—has never been remotely tested, as noted in the prior chapter. (As we have seen, much smaller tests of the primitive-tools-and-methods thesis have failed.)

Since no one can demonstrate how these granite blocks even reached Giza, there is no point in speculating on how they were put in place to form the room referred to as the King’s Chamber. That involved lifting them up 175 vertical feet, and no team of men pulling on ropes could achieve that feat.

The whole “how-the-pyramid-was-built exercise” is a dodge. It assumes that the blocks could be quarried and transported using primitive tools and methods; however, they could not. How many more generations are going to keep going in futile circles trying to prove this or that arbitrary, nonsensical thesis?

In fact, these issues can be scientifically resolved. It is quite possible to test and attempt to duplicate what Egyptologists claim occurred at the quarry. Every step can be performed using primitive tools and methods, as outlined by historians. This is one of the only areas of history and archaeology that can be tested using scientific methodology.

I propose that this simple “proof-of-concept” test be performed by an independent scientific body. This would definitively put the debate to rest, and “we” could move on to more productive lines of research. This is a critical point, and that is why it is being repeated here.

The next extreme challenge occurred during the actual construction project. As the engineers supervised the project, making sure that each tier was a flat plane, they had to take the interior design into account. Their design includes passageways, a space (Grand Gallery) with a corbelled ceiling, two rooms (King’s and Queen’s Chambers), and a complex duct system that snakes from the inner chambers through multiple tiers.

In 1995, Christopher Dunn, an aerospace engineer and author of The Giza Power Plant, investigated the “sarcophagus” of the Great Pyramid. Using precision measuring instruments, he climbed inside to gauge the degree of precision used in creating the granitic object.

Dunn soon discovered that the box was so smooth and flat that a flashlight shone from behind a straight edge ruler*1 would not reveal any light passing through it. All the edges on the box were uniformly square and the surfaces completely flat.

Since Dunn couldn’t find any significant deviation across the flat surfaces and square corners, Dunn eventually concluded that the level of precision achieved could only have been arrived at by using some type of advanced machinery.

Numerous other disinterested observers and researchers have noted these same high levels of precision that were achieved in the granite blocks that frame in the King’s Chamber and the casing stones sitting on the lowest tier. These stones were planed and positioned with such precision that a piece of paper cannot be inserted between them.

A civilization can only produce high levels of precision on this kind of grand architectural level using sophisticated technology. In addition, the earliest civilizations to require precision building techniques were the ancient Greeks and Romans, the latter with the design of the Coliseum, but they built that sophisticated structure thousands of years after the Great Pyramid was constructed.

In order to justify the claim that the ancient Egyptians could produce such precision using primitive tools and methods, Egyptologists should have easily been able to quarry, lift, transport, and raise the thirty-five-ton obelisk. As we have previously noted, this challenge was, in fact, a very low-level test.

The same was true for the prior Japanese attempt to build a scale model of the Great Pyramid. In both cases, the primitive tools and methods failed, and the teams had to rely on modern equipment to get the job done. Clearly, Dunn’s conclusions agree with the facts, as they would predict the failures of the above-described tests.1

Very similar levels of precision had to be achieved to ensure that each tier was flat in order to create a true pyramidal shape. Precision on the scale of a forty-eight-story structure—composed of millions of blocks of stone—is simply unthinkable given granite hammer stones and primitive manipulation methods to achieve it.

(In actuality, it would be difficult to achieve today: this is considered in the next chapter.)

The objections to the orthodox scenarios are so strong, numerous, and rational that one can only wonder why Egyptologists tenaciously cling to them. The answer to that question is not as complicated or as irrational as it might seem on the surface. (This is addressed in the next section.)

THE GANTENBRINK SHAFT

The Gantenbrink shaft, named for the German robotics engineer Rudolf Gantenbrink, also displays that a high degree of precision engineering was employed by the pyramid’s builders. Egyptologists once considered this to be an “air shaft” and later thought that such shafts—the entrances to which are found in both chambers—might be “soul shafts,” designed to direct souls to the afterlife, until a robot sent to explore the small eight-inch by eight-inch shaft ran into a small, copper-handled door that blocks passage.

Fig. 5.2. The Gantenbrink shaft and door (approx. 8" × 8")

No one knows the shaft’s actual purpose.

THE SPHINX DATING CONTROVERSY

John Anthony West, an independent researcher, was inspired to investigate the Sphinx complex by an earlier investigator, R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz. The primary issue that West’s mentor raised was the incongruity of the apparent erosion patterns evident in the complex with the views of orthodox Egyptologists concerning their chronology.

After carefully examining these weathering patterns, West became convinced that they were caused by a period of extensive rainfall.

Since the Giza Plateau is in a desert environment and there was not a period of extensive rainfall during the era following the assumed building of the Sphinx in 2500 BCE, that conclusion came into direct conflict with the orthodox time line.

Fig. 5.3. The Great Sphinx

Of course, West was keenly aware of this mismatch. Not himself a geologist, he called in Robert Schoch, a credentialed geologist and an associate professor of natural sciences and mathematics at Boston University, to conduct a scientific investigation of the Sphinx complex.

After carrying out a thorough examination of the precinct using all of the knowledge and technological equipment commonly employed by geologists, Schoch concluded that the Sphinx erosion patterns were indeed caused by rainfall.

This prompted the geologist to find out when the last era of extensive rainfall had occurred in North Africa. Schoch discovered that that epoch had taken place about fifteen thousand years ago. When he announced his findings and redated the age of the Sphinx, it ignited a firestorm of controversy.

This often-bitter controversy has raged on for more than two decades, and it has not been resolved even at this late date. In truth, I am not that concerned with the outcome. What is important to the Genesis Race theory is what transpired at a conference held by the Geological Society of America in 1991.

The conference attendees heard Schoch’s geological arguments for the redating. Then Lehner took the podium and gave the audience the results that contradicted Schoch’s conclusions.

During his presentation, one key point that Lehner raised about the redating was the fact that there were no human tribes or cultures identified in the region that were capable of building the complex at that early period.

That point really had nothing to do with the science of geology, which was the focal point of the Sphinx controversy. Nonetheless, it did reveal why Egyptologists stubbornly hold on to their positions.

Stripped of the ancient Egyptians, circa 2500 BCE, using the established tools and methods of that period, they have no answer to the question of who constructed the Sphinx or the Great Pyramid and how those feats were accomplished.

Lehner’s point was neither illogical nor was it incomprehensible; in fact, it was internally consistent with the logic used by the orthodoxy to this day. The problem is that the mounting evidence does not support the orthodox theories.

It simply does not matter that the attempts by Egyptologists to demonstrate their beliefs have failed; nor does it matter how many substantial objections have been raised by skeptics. They cling to their beliefs.

The time line and the efficacy of the primitive-tools-and-methods thesis constitute central dogmas that the orthodoxy simply cannot abandon, regardless of the evidence to the contrary. Though understandable in a broad cultural context, that position necessitates making the observable evidence fit their theories.

Of course, that position is entirely opposite to scientific methodology, which must make theories fit the evidence.

Archaeologists and historians can skirt around this issue because these disciplines are not within the purview of the hard sciences, such as geology. So introducing a geologist into the mix completely threw orthodox Egyptologists off-kilter. Suddenly, they had to meet the challenges posed by the supposedly hard science of geology.

There is more at stake in this controversy than the redating of the Sphinx complex.

Unfortunately, the contrary opinions of two credentialed geologists concerning the exact same geological features has revealed the fact that geology is not quite the hard science that the public has been led to believe it is. The facts it arrives at are also open to diverse interpretations.

In my view, the Sphinx controversy is not the central issue to resolve. The key objections to the orthodox theories involve (1) quarrying, transporting, and positioning the fifty- to seventy-ton blocks of granite 175 vertical feet above the base of the Great Pyramid, and (2) duplicating the high level of precision engineering evident in the overall construction of the Great Pyramid.

Given the total preponderance of the evidence, I am compelled to conclude that the primitive-tools-and-methods theory is untenable. Lacking any evidence that a technologically advanced human civilization existed at that time, we are then forced to consider other possibilities.

The Great Pyramid and the massive obelisks exist, and someone, a reasoning body, had to put them there using some form of advanced technology. There is a truth behind these mysteries, however well concealed it might appear to be.

I propose that an advanced Type II or III civilization constructed the complex, intentionally placing the Great Pyramid, as a geodetic marker, on the 30° north parallel latitude and the adjusted 0° longitude (rather than the Greenwich Prime Meridian). Long before that, they had seeded the planet, and prior to that event they had set planetwide engineering principles in motion.

ADDITIONAL EVIDENCE

The Great Pyramid was hermetically sealed at the time the caliph Mamun decided to bore through the limestone blocks to find the pharaoh’s treasures he believed lay inside the massive complex. He used several simple yet ingenious means to penetrate through the limestone exterior: the applications of vinegar, fire, and hard labor.

After an extensive period of intense labors, his crew managed to bore through the exterior stones; they were fortunate in the fact that they ran right into a passageway. After combing through the interior using torches to light the pitch-dark passageway and Grand Gallery, they finally came to the room referred to as the King’s Chamber.

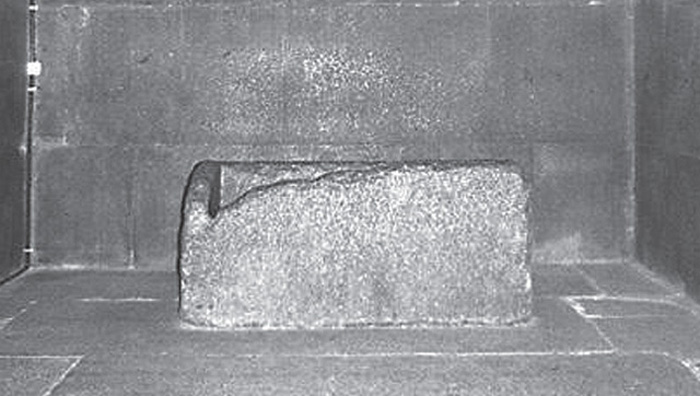

Fig. 5.4. King’s Chamber box

What did they find when they managed to get to this room? The caliph and his crew were crestfallen to be confronted by an empty room and an equally empty coffer. There were no valuable objects and no remains of any pharaoh.

No one had previously penetrated into the pyramid’s interior, so no grave robbers had gotten there first and removed the hoped-for treasures.

Obviously, the above historical facts cast very serious doubts on the “tomb theory.” If the caliph had found a mummy in the coffer, such would not be the case. We might dismiss this lack as representing an exceptional case if it did, in fact, not represent similar findings in the other 103 large pyramid complexes that dot the Egyptian landscape.

The traditional Egyptian burial sites found in the Valley of the Kings, for instance, did contain treasures and the remains of pharaohs when they were discovered. However, the massive pyramids did not.

These distinctions appear to have escaped the public, who often blindly accept the theories of Egyptologists that are routinely recited in history books and aired on TV specials.

However, the ever-growing database available on the Internet is changing that situation as the anomalous facts are presented on many websites.

King Tut’s burial complex displayed the traditional features of an Egyptian tomb: colorful murals adorned the walls, treasures filled the chamber, and canopic jars were carefully set on the floor. None of that was present within the Great Pyramid. The walls were bare, the “coffers” empty, and the floors devoid of the usual objects associated with traditional Egyptian tombs.

Given this, how can Egyptologists assert that the pyramids are nothing more than giant mausoleums without any evidence to back up the claim? They cannot in any scientific way, but they do nonetheless, for reasons outlined above.

Next, the ancient Egyptians were devoted lovers of artwork. Their artists depicted every aspect of the environment and the culture. No one who has examined the extensive record of Egyptian murals and other works of art would deny this fact. Then why do we not find the most obvious features of the Egyptian landscape, the pyramids, especially the Great Pyramid, depicted in this extensive record?

The absence could be due to the fact that the artists did not consider the pyramids a part of their cultural record. Were they, even then, mysterious artifacts—attributed to a mysterious race of vanished gods—that triggered awe, fear, and wonderment, as they have for the millennia that have followed that remote era?

Egyptians of the 800 CE era typically informed travelers who came to visit the Great Pyramid that they called it “the house of terror.” That does not sound like a cherished artifact made by the natives.

We have several other objections to the orthodox theories. The Great Pyramid displays neither any hieroglyphs nor any obvious attestations. These we would also expect to find associated with traditional tombs and other Egyptian edifices.

Ascribing responsibility to—and taking credit for—any feat is a very human characteristic, one exhibited by every advanced culture.

In addition, there are no ancient papyrus documents that contain references as to how or why the Great Pyramid was designed, engineered, and finished. We do not find any blueprints in this important record. Engineer Craig Smith, who was quoted in chapter 4, notes:

No records have been found that relate to the design of the Great Pyramid . . . they had no pulley.2

Does it not seem odd that this colossal accomplishment was not copiously documented and inscribed with dedications and inscriptions regarding Pharaoh Khufu, as other true Egyptian tombs in the King’s Valley were?

If the Egyptians built it, they would have claimed it in BOLD CAPS in their papyrus records and in obvious hieroglyphic sequences. This is yet another piece of circumstantial evidence that argues against the Egyptians and for the Genesis Race having built the Great Pyramid and the other pyramids.

Despite all of this evidence to the contrary, Egyptologists continue to assert that the Great Pyramid is nothing more than a giant tomb. I have outlined the reasons already. They have to have a chronology and a history to justify their own existence as historians and scholars. To admit to any chinks in their armor would risk losing that battle and then the war.

But what about the apparent coffins in the King’s and Queen’s Chambers? Though they appear to be coffins, they did not contain any remains, so it appears that they were not ever used as coffins.

Then, if the Great Pyramid was not a tomb, what was its purpose?

(Actually trying to answer that question needs to be preceded by the proof of concept testing that I proposed in the previous chapter.)

THE NULL HYPOTHESIS

As noted in earlier chapters, we should not expect any advanced civilization to act in accordance with our logic and behaviors. The existence of apparent coffins absent of any remains may look like an insoluble paradox to us from our entirely homocentric view. Yet if we shift our perspective, we might just run into the reasoning behind this and other enigmas.

The lack of mummies, the lack of hieroglyphics and other kinds of attestations, and the existence of seemingly purposeless features in the interior—such as the three-hundred-foot-long descending passageway, the “air ducts” (do the dead breathe?), and the massive Grand Gallery—may actually represent clues that the builders left behind.

These clues seem to be based on null thought processes. If humans routinely bury their dead in coffins, then build a coffin but leave it empty. If they routinely ascribe credit to the achievements of individuals and groups, then leave the credits out. If they anticipate discovering hidden treasures within a hermetically sealed structure, they will eventually enter and find nothing.

The final null clue is the very massive, precision-engineered structure itself. If it was not a tomb, then what was its purpose? (Of course, that question vexes us to this day.) Build a sophisticated structure that has no obvious reason as to its end use and you leave it a perpetual mystery. Let the primitives stare in dumbfounded awe until they decipher the embedded code, if they ever do.

As was noted in prior chapters, we must assume that advanced extraterrestrial technology would be invisible to us. We should consider the possibility that what appear to be unsolvable mysteries are actually well-cloaked clues. Taken as single, isolated artifacts, they do, in fact, appear unfathomable. However, taken as a whole, they seem to embody a well-concealed yet potentially decipherable code.

The first step in understanding that code is to realize that the early Egyptian civilization did not build the Great Pyramid, but some as yet unidentified civilization surely did. At this point, we—the global human collective—do not seem to have arrived at that stage. After all is said and done, Egyptologists still embody our institutional position when it comes to the apparent mysteries that the Great Pyramid poses.

THE SECOND AND RED PYRAMIDS

Though the Great Pyramid commands the most attention, in fact, several other pyramids nearly equal it in size and would have required the same level of knowledge, the same engineering and project management skills as the larger pyramid.

The Red Pyramid is located at Dashur, not far from Giza, and is about the same size as the Pyramid of Cheops. It is the largest of three major pyramids located at this site, soaring 341 feet above the desert floor with a base that extends for 722 feet. Named for the rusty, reddish hue of its stones, it is also the third largest Egyptian pyramid, after the two described above. It contains a corbelled-arch gallery in the interior that resembles the one in the Great Pyramid.

This ancient site is thought to be older than the Giza complex, though there is no definitive proof to back up that assertion. At the time of its completion, the Red Pyramid was the tallest man-made structure in the world. It is also believed to be the world’s first successful attempt at constructing a “true” smooth-sided pyramid. Local residents refer to the Red Pyramid as el-harem el-wa-wa, meaning the “Bat Pyramid.”

Oddly, this pyramid was also finished with an outer layer of Tura limestone blocks, but only a few of these now remain at a corner of the pyramid’s base, as with the Great Pyramid. This seems a strange coincidence. Supposedly, the outer casing was carried away during the Middle Ages, when, it is posited, much of the white Tura limestone was taken to rebuild Cairo.

The theory is that the locals took the trouble to dig through the fallen casing stones after a fourteenth-century earthquake knocked them loose. Though this scenario is at least feasible with the Great Pyramid, which lies at the edge of Cairo, the same cannot be said of the one at Dashur. There would not be any need to venture ten miles away to labor to break up limestone blocks and haul them to Cairo since there was an ample supply at Giza.

Additionally, why do the casing stones still exist on the so-called Bent Pyramid at Dashur if that single earthquake was powerful enough to dislodge the casing blocks from the other two huge pyramids?

There are many other pertinent questions that need to be answered about the missing casing stones at many of the sites, which seem to suggest the Egyptian pyramids were built in remote antiquity, not 4,500 years ago.

CONCLUSION

The Great Pyramid is not just a massive edifice; it also is a precision-engineered structure that exhibits features that could not have been built using the known primitive tools and methods that Egyptologists ascribe to its construction. Though test projects to build such structures using these primitive means have been conducted, they have repeatedly failed.

In spite of that fact, the orthodoxy still maintains that the ancient Egyptians built the complex, largely because they have no alternative builders to consider among established human cultures.