14

• • • • • • •

Policeman Escorted Aboard the Ship

Date: December 3, 1967

Location: Ashland, Nebraska, United States Police sergeant Herbert Schirmer, age twenty-two and an honorably discharged Vietnam veteran, was on patrol when he encountered something hovering above the road; the object had a flashing red light. Surprised and unsure of what it was, the patrolman flashed his high beams at it.

For an instant, he thought it might be a truck having engine trouble, but as his eyes focused he could see it was nothing of this Earth.

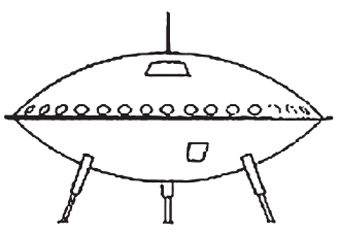

Instead, a disk-shaped object displaying a shiny, polished aluminum surface hovered before his disbelieving eyes. The blinking red lights were shining out from portholes on the sides of the craft. The UFO was hovering six to eight feet above the ground on Highway 63. It was 2:30 a.m. when the incident occurred.

As he fixed his gaze on it, the craft began to slowly ascend; at the same time, he noticed a siren-like sound accompanying the ascent while a flame shot out from the underside. He later remembered sticking his head out of the window and watching the UFO depart, quickly shooting up into the night sky.

Shaken but still rational, he got out of the car, carrying his flashlight to inspect the surface of the road where the UFO had hovered, almost hugging the ground. After this, he drove to the police station and wrote the following terse description in the logbook: “Saw a flying saucer at the junction of highways 6 and 63; Believe it or not!”

Fig. 14.1. Spaceship sketch by Sgt. Herbert Schirmer

He was puzzled to notice that it was 3 a.m., as the sighting seemingly lasted no more than ten minutes.

As the morning wore on, Schirmer contracted a headache and a “weird buzzing” in his head, and he discovered that he had a “red welt” on his neck. It was about two inches long and approximately half an inch wide, located on the “nerve cord” below one of his ears. A few hours later, Chief Bill Wlaskin visited the alleged encounter site and found a small metallic artifact.

Troubled by the lingering feeling that he had “lost” some time, Schirmer agreed to undergo hypnotic regression therapy. He was to find out that the short sequence of events that he could consciously recall was not all there was to the event.

The sessions revealed that the occupants of the landed craft came and took him aboard the craft. They were able to communicate with him through some form of mental telepathy. The aliens told him that they would visit him twice more and that one day he would “see the universe.”

Under hypnosis, Schirmer recalled how humanoid beings between four and one-half to five feet tall escorted him from his car and into the ship. Once inside, the “leader” gave him a tour and explained various things about themselves and their mission on Earth.

He described the entities as having slightly slanted “catlike” eyes; with gray-white skin; and long, thin heads with flat noses and slitlike mouths. They wore silver-gray uniforms, gloves, and helmets (which had a small antenna on the left side around their ear), and at the left breast of each suit, they had the emblem of a winged serpent. Schirmer had the impression that the small antennas were somehow a part of their communication process with him.

The young patrolman said that he was given an extensive amount of unsolicited information by one of the crew. Schirmer described the alien’s voice as seeming to come from deep within him, but he says he also simultaneously received input that must have been through telepathy. Though there is more, I am going to focus on three aspects of Schirmer’s memories.1

First, when asked by the hypnotist to describe the craft’s interior and its propulsion system, Schirmer replied, “The ship is operated through reversible electro-magnetism. . . . A crystal-like rotor in the center of the ship is linked to two large columns . . . those were the reactors. . . . Reversing magnetic and electrical energy allows them to control matter and overcome the forces of gravity.”2

Though the rookie patrolman was young, he was also a veteran and a reasonable, serious-minded individual. No evidence has ever been presented showing that he had ever paid any attention to the subject of UFOs, and Schirmer made statements to that effect.

At one point during the interview, the interviewer decided to test Schirmer’s knowledge of the field. He was asked whether he had heard of Barney and Betty Hill (a couple who had been abducted by a UFO years earlier in a famous case). Schirmer paused for a moment, obviously thinking, and then replied, “Oh, yeah, they were those outlaws in that movie.”

He must have been one of a minority who had not heard of the continuing publicity concerning that abduction just six years previously.

No one who treated or spoke with Schirmer thought he was prevaricating. Nonetheless, when the skeptics crawled out of their dark holes, Schirmer was said to have hallucinated the events. That is a serious accusation that could cost a rookie policeman his job.

But those who are quick to cast aspersions on the character of good, honest people who happen to encounter UFOs have no concern about anything but their own cherished worldview (or perhaps they are simply doing their jobs as paid disinformation specialists).

That view does not permit extraterrestrials to fly through Earth’s skies in advanced spacecraft. How do they know this to be true? They do not; that is just their belief. In fact, there is no scientific principle of physics that forbids a civilization that is technologically advanced enough from visiting our planet. None.

But those with a dogmatic worldview could care less about the facts or other people’s experiences of them. All that matters is their personal belief system.

Skepticism is warranted in any scientific or legal enterprise where the facts have to be determined and explained using the best available evidence. However, there are limits to human perceptions and to the ability to establish “the truth” in any endeavor that involves complex circumstances. Invariably, different witnesses give contradictory testimonies in court when describing the same series of events.

How are the facts established? By the way the preponderance of the evidence comes down, how logical the arguments are, what the character of the key witnesses is established to be, and so forth. It is easy for anyone to trash a UFO witness and for government officials to trash their own military personnel.

However, what if we put the spotlight on them and ask how they know what they claim to know about a situation that they themselves were not witness to? Am I going to accept the testimony of a fighter pilot who reports a UFO sighting or that of his superior officer who “knows” that UFOs do not exist?

Schirmer had a job to do, and he was carrying out his duties. His sheriff confirmed his good standing.

Actually, the alleged abductees’ credibility problem was not just the fault of the government or civilian debunkers; it also involved the UFOlogy community itself. Though they were well intentioned, in the early days of UFO research, the organizations were concerned about being taken seriously by scientists and the general public.

In that context, a mass sighting over Washington, D.C., verified by military personnel was credible, but an individual claiming to have been abducted and talked with aliens face-to-face—that was over the edge.

Schirmer had been on the police force for seven months when the incident occurred. He had served a tour in the navy and was ready to settle down in Ashland. Unlike his father, he did not plan to make the military his career, though he described himself as a military brat.

He was later described as a stolid, unimaginative, no-nonsense kind of person by people in Ashland. In fact, he was the exact type that makes a good cop. Add to that the fact that he was six feet, three inches tall and weighed 220 pounds.

Ashland was a small community, and Schirmer was one of only three officers on the force. He came on duty that night at 5 p.m. The rookie followed his usual routine, patrolling the back streets and alleys of the town. Around 1:30 a.m., he started to get an uneasy feeling. Dogs were barking and howling. The cattle were making a lot of noise, bawling and bellowing. He told an interviewer, “There was big bull in a corral. He sure was upset. He was kicking and charging the gate. I made sure the gate would hold. I scanned the area with my spotlight. There was nothing out of the ordinary.”3

He decided to continue his patrol route and checked a couple of gas stations along U.S. Highway 6. At 2:20 a.m., he continued southwest. He drove on, and when he neared the intersection with Highway 63, he spotted the flashing red lights he mistook for a truck. The details clarify why he originally had difficulty identifying it. When he first saw the lights, a small ridge partially obstructed his full view.

The lights were coming from his right; he drove past the source and then swung around on a loop road. At that point, he checked his watch and noted it was 2:30 a.m. He later described the UFO as being football-shaped and at least as wide as the road. The craft was hovering just above the level of the top of his head.

The portholes were about two feet in diameter. Beneath the craft, he noticed a catwalk that encircled it. He did not notice any odors, smoke, or exhaust. Curiously, the young cop never mentioned being frightened by the alarming, unearthly events. At least he did not do so consciously. That changed under hypnosis.

Schirmer calculated that the entire event had lasted no more than five minutes. When he drove back to the station, which took another five minutes, it was 3:00 a.m.; he had lost twenty minutes from his memory. This is not unusual in abduction cases, as we shall see in chapter 17, which discusses the abduction of Kelly Cahill.

When Wlaskin read Schirmer’s terse report, he went straight to his house. Wlaskin later told a reporter at the Lincoln (Neb.) Journal, “I put the question right to him. And he told me what he saw. . . . I don’t doubt him . . . he saw something and reported it the way he saw it.”4

Even though the chief was willing to back him up all the way, Schirmer wanted to take a polygraph to prove his story. He did and passed with flying colors. However, at the same time, he was experiencing some symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder.

He had felt ill right after the incident and was continuing to get headaches and to hear a buzzing sound before going to sleep. At that point in time, Schirmer had not retrieved the lost twenty minutes.

Of course, the mass media picked up the event, and in short order Schirmer received visits from representatives of the Condon Committee.5 This was the informal name for the University of Colorado UFO Project, which was funded by the U.S. Air Force from 1966 to 1968 and was under the direction of physicist Edward Condon. The Condon Committee itself has since been debunked as having an anti-UFO bias embedded in it.

After interviewing Schirmer, the committee decided to review his case since it was compelling and he was a credible witness. Thinking that he was a naive young cop from the sticks, they invited him to come to Colorado to appear before a study group.

They baited the hook by telling him that Condon would be in attendance. However, they knew that he would not be. A very interesting and embarrassing scene developed when the Condon cons tried to pass off a stand-in to Schirmer. However, he had learned Condon’s first name was Edward prior to the interview.

Veteran UFO investigator Jacques Vallée was in attendance, and he tells the story this way:

When Sergeant Schirmer arrived in Boulder for a series of psychological tests he asked to see Professor Condon; he had been induced to make the trip because of its potential scientific significance. He had been assured that serious interest in his sighting existed and that professor Condon, the well-known physicist would attend the session in person.

Unfortunately, Dr. Condon was not on campus at the time, and the scientific committee realized that the trick they used to get the officer to come and to be tested threatened to be exposed. So Sergeant Schirmer told me they introduced someone else to him as Professor Condon.

Schirmer was no fool. During the ensuing conversation, somebody came into the room and addressed “Professor Condon” by a first name which had no resemblance to Edward or Ed. Schirmer confronted the scientist. “You’re not Condon,” he cried, and a very embarrassing scene followed.6

Schirmer underwent a hypnosis session at that time with Leo Sprinkle, Ph.D., author of Soul Samples: Personal Explorations in Reincarnation and UFO Experiences and founder of the annual Rocky Mountain UFO Conference. Under hypnosis, he painted a slightly different picture of the “abduction” event, as the below list indicates:

- The police car stalled or stopped.

- The headlights went off during the sighting.

- Schirmer was “prevented” from taking his gun out.

- He was “prevented” from using his radio.

- A bright light was emitted and shone into his squad car.

- Schirmer observed a blurred white object sent from the UFO; the object approached the car and appeared to be intelligent.

- Some sort of conversation occurred between him and the object.

- Communication with someone in the craft occurred at the time of the UFO sighting, and a feeling of direct mental contact with someone was occurring at the time of the interview with the study group.

- Information was obtained that indicated that the craft was propelled by some type of electrical and magnetic force that could control the force of gravity.

One wonders whether Sprinkle ever paused to consider the damage done to people in Schirmer’s shoes. This is a very significant sociological issue, especially here in the United States.

For instance, back in Ashland, an effigy of Schirmer was hanged from a tree near the north gate of the Ashland cemetery. He had become the object of ridicule and scorn to some of the townsfolk. He also received an anonymous phone call telling him that his car had been bombed, which was untrue.

Schirmer later confessed to having been disturbed by the ridicule and accusations that were soon directed his way, but for a time, he shrugged them off.

Still, Wlaskin had confidence in his rookie cop. Two months after the Condon trip, the sheriff resigned and Schirmer was appointed chief of police of Ashland. However, by then he was having trouble concentrating and was bothered by the social side effects of public disclosure, and several months later he resigned. (This is also what happened in the Zamora case.)

The Condon Committee released its findings a year later. Schirmer’s case was rejected out of hand for lack of evidence and because he apparently did not pass their “psychological” evaluation.

However, the case was yet to be closed as far as Schirmer was concerned. He contacted a writer with experience in UFO investigations by the name of Warren Smith. He told Smith that he was plagued by headaches and insomnia.

Smith arranged for him to meet author Brad Steiger, an investigator into paranormal topics. After that meeting took place, Smith suggested that Schirmer undergo another series of hypnosis sessions.

Loring Williams, a professional hypnotist, put Schirmer under and regressed him back to the events. What follows is his account of what happened that night, given while under hypnosis.

Schirmer said that he drove up the hill and into a field above a road known as a local lovers’ lane and beer party site. He tried his radio, but it would not work. The engine of his squad car died, and the lights went out as well. Three telescoping legs descended from the bottom of the UFO, and it settled on the ground.

Then physical entities emerged from the ship and came to his car. Schirmer tried to draw his revolver but could not. One entity stood in front of the car holding something that was emitting a green gaseous substance, which enveloped the car. A second entity pulled out some kind of device from a holster and pointed it at Schirmer’s car; then a blast of light hit him, and he lost consciousness momentarily.

Here we must pause to consider this version’s departure from Schirmer’s earlier accounts. In this session he stated that the UFO actually landed. Now, as with the Zamora case, that should have left some trace depressions in the ground along with flattened, desiccated patches of grass. However, none of that kind of evidence was found at the site by the Condon investigators.

Smith claimed to have found such evidence when he conducted his own investigations, but his findings are suspect because he failed to take any supporting photos. That alone makes him a shoddy investigator.

The way this case kept evolving and changing brings up two points about UFO investigations and investigators: (1) professionally trained investigative journalists are almost never involved, and (2) as seen in the Roswell case (where a science fiction author, Kevin D. Randle, conducted an investigation), the lack of a professional methodology for establishing the credibility of potential witnesses undermines the results of the investigation.

Bringing hypnotists into early UFO cases was standard practice at the time. However, in retrospect, the results of hypnotic regression are always open to skepticism. Each time Schirmer was regressed, he provided yet more sensational details about the craft and its occupants. These included the following statements:

- The ship drew power from electrical lines and from water.

- The craft was powered by some kind of reverse electromagnetic engine.

- The aliens had mother ships located beyond detection as well as bases on Earth and Venus.

- The aliens said they were not hostile toward human beings.

- Their purpose involved monitoring Earth.

CONCLUSION

The Schirmer case is of great interest as much for what it reveals about how early investigations were conducted—by scientists and UFOlogists—as for the UFO sighting itself. While there is a kernel of objective truth to it (as the sheriff states, “He saw something”), no one can establish whether Schirmer’s accounts beyond the initial stages of the sighting are real or not. This case lacks the corroborating witnesses and trace evidence that the Zamora case contained, so it is not as strong. However, he was a credible witness who had a close encounter.