30

• • • • • • •

Vimanas

The Flying Machines of Ancient India

Like the Old Testament, the Hebrew Torah, and the Sumerian Enumma Elish, the Vedas are a collection of ancient Sanskrit epics, scriptures, and written histories from India. However, the Vedas extend beyond those texts by containing references to flying airplanes and spacecraft known as vimanas.

Unlike the Hebrew and Sumerian traditions, which were unclear about the exact nature of the sophisticated mechanized technology the people were witness to, the Vedas are very specific about its nature and characteristics.

According to Venkataraman Raghavan, the former head of the Sanskrit Department of India’s prestigious University of Madras, “Fifty years of researching this ancient work convinces me that there are livings beings on other planets and that they were visiting the earth as far back as 4000 B.C.”1

This is consistent with the time line established for cosmic intervention prior to disseminating the tools of civilization, as in Sumer.

The Sanskrit scholar went on to note, “There is a just mass of fascinating information about flying machines, even fantastic science fiction weapons, that can be found in translations of the Vedas (scriptures), Indian epics, and other ancient Sanskrit text.”2

The vimanas are variously described throughout the texts. Some accounts tell of their exact flight characteristics and also of the powerful weapons they harbored. Consider the following passage from the Yajur Veda:

O royal skilled engineer, construct sea-boats, propelled on water by our experts, and airplanes, moving and flying upward, after the clouds that reside in the mid-region, that fly as the boats move on the sea, that fly high over and below the watery clouds. Be thou, thereby, prosperous in this world created by the Omnipresent God, and flier in both air and lightning.3

When we take into account the fact that the earliest Hindu religious traditions, entirely disconnected from the Hebrew or Sumerian traditions, also agree on the fact that extraterrestrial vehicles whirled through the skies over Earth, the evidence has gone from strong to compelling; as do the craft in eyewitness accounts given by the ancient Hebrews, the vimanas share many of their characteristics with the modern UFOs.

They are described as being able to navigate to great heights and speeds using quicksilver and a great propulsive wind. Another account, this one from the Sanskrit Hindu epic the Ramayana, says:

The Puspaka car that resembles the Sun and belongs to my brother was brought by the powerful Ravan; that aerial and excellent car going everywhere at will . . . that car resembling a bright cloud in the sky. . . . And the King [Rama] got in, and the excellent car at the command of the Raghira, rose up into the higher atmosphere.4

Again, we find references to an extremely bright, shining light that is as brilliant as a white cloud reflecting direct sunlight. The Ramayana also describes a splendid chariot that “arrived shining, a wonderful divine car that sped through the air.” In another passage, there is mention of a chariot being seen “sailing overhead like a moon.”5

In the Mahabharata, a Sanskrit Hindu epic, we read that at Rama’s command, “the magnificent chariot rose up to a mountain of cloud with a tremendous din.” Another passage reads, “Bhima flew with his Vimana on an enormous ray which was as brilliant as the sun and made a noise like the thunder of a storm.”

This sounds very much like Jehovah on Mount Sinai.

The Vymanika-Shastra (also known as Vymaannidashaastra Aeronautics) is a Sanskrit text on the science of aeronautics. It was written in the early twentieth century but was alleged to have been psychically delivered to the author by an ancient Hindu named Maharishi Bharadwaaja. In the work, there is a description of a Vimana: “An apparatus which can go by its own force, from one place to place or globe to globe.”

The text also lists sixteen kinds of metal that are needed to construct the flying vehicle: “Metals suitable, light are of 6 kinds.” However, only three of them are known to us today. The rest are lost to antiquity. Professor of aeronautics A. V. Krishna Murty at the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore has studied these texts and has said:

It is true, that the ancient Indian Vedas and other text refer to aeronautics, spaceships, flying machines and ancient astronauts. A study of the Sanskrit texts has convinced me that ancient India did know the secret of building flying machines—and that those machines were patterned after spaceships coming from other planets.6

In the Mahabharata, the king, Asura Maya, has a vimana that measures twelve cubits (about 40 feet) and is equipped with missiles and has four wheels. The Samarangana Sutradhara goes beyond the Old Testament, which merely describes Jehovah hovering over Moses’s tent and speaking with him, to give an actual description of the construction of the vimana, which follows:

Strong and durable must the body of the Vimana be made, like a great flying bird of light material. Inside one must put the mercury engine with its iron heating apparatus underneath. By means of the power latent in the mercury which sets the driving whirlwind in motion, a man sitting inside may travel a great distance in the sky. The movements of the Vimana are such that it can vertically ascend, vertically descend, moves slanting forwards and backwards. With the help of the machines human beings can fly in the air and heavenly beings can come down to Earth.7

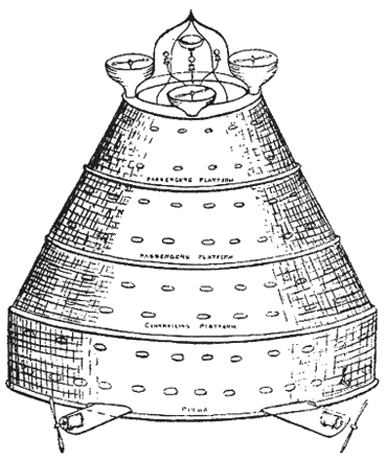

Fig. 30.1. The flying machines known as Vimanas. Drawing by T. K. Ellappa, 1923

This passage evokes the whirlwind flight characteristic contained in the Torah and includes both human and extraterrestrial beings in flight together. The Rig Veda, along with the Enumma Elish, the oldest text document known, includes references to the following modes of transportation:

Jalayan: a vehicle designed to operate in the air and water (Rig Veda 6.58.3)

Kaara-Kaara-Kaara-Kaara-Kaara-Kaara: a vehicle that operates on the ground and water (Rig Veda 9.14.1)

Tritala-Tritala-Tritala: a vehicle consisting of three stories (Rig Veda 3.14.1)

Trichakra Ratha: a three-wheeled vehicle designed to operate in the air (Rig Veda 4.36.1)

Vaayu Ratha: a gas- or wind-powered chariot (Rig Veda 5.41.6)

Vidyut Ratha, Vidyut Ratha: a vehicle that operates on power (Rig Veda 3.14.1).

Flying vehicles were initially called rathas (vehicles or carriages) in the Rig Veda, as they were called chariots in the Old Testament. The ratha and later vimana could fly at a very high rate of speed. The ratha was triangular and very large, and it had three tiers and was piloted by at least three people (tribandhura). It had three wheels, and in one verse the chariot or carriage was said to have had three columns.

These craft were generally made of any one of the following three kinds of metals: gold, silver, or iron, but the metal that usually went into their makeup, according to the Vedic text, was gold; long nails or rivets held them together. The chariots had three different types of fuel.8 References to flying vehicles occur in the Mahabharata forty-one times, of which one air attack deserves special attention. The account records the events surrounding the Asura king Salva, who had an aerial flying machine known as Saubha-pura, which he used to attack Krishna’s capital, Dwaraka.

It tells how the king showered missiles from the sky. As Krishna chased him, the king flew near the sea and landed on the high seas. Then he came back with his flying machine and mounted a second attack against Krishna, hovering about one krosa (about four thousand feet) above the ground. Krishna retaliated with a powerful ground-to-air weapon, which hit the aircraft in the middle and shattered it into pieces. The damaged flying machine then crashed into the sea.

Another vivid description of this aerial battle also occurs in the Bhagavata Purana. There are similar references to missiles, armaments, sophisticated war machines, mechanical contrivances, and vimanas in the ever-popular Mahabharata.

It is interesting to note that among the types of vimanas mentioned in the Mahabharata are (1) the shakuna (bird-shaped), (2) the mandara (mountain-shaped), and (3) the mandala (circular-shaped), the latter being the type most typically observed in modern times. Vimanas are also mentioned in the Ramayana, and they have many qualities and descriptions that fit those described in the Vymanika-Shastra.

The Mayamanta draws on much older material from the Mayamata, which is ascribed to Maya Danava, the architect and artist of the demons, who is said to have created these flying machines for the gods and demons. The Padma Purana mentions that there are four hundred thousand types of “manusha-like,” or humanlike, entities in the cosmos.

These references are of great interest since they allude to the existence of other humanlike races, which the Old Testament and the Enumma Elish do as well; that is, the gods who created man in their image, the Anunnaki, and the sons of the gods.

This harkens back to the biblical reference to the hybrid race created by the union between the sons of the gods and human women, as well as to the existence of the Nephelim at the same time.

Some of these races are superior (gods) and others inferior (demons). Then there are the nonhuman entities: the nagas, the monkey-type races, the cherubim, and so forth that also inhabit other worlds and occasionally interface with humans on Earth.

Like Egypt and Sumer, India has its very ancient and very mysterious artifacts, which have thus far defied scientific explanation. Though modern scholars pooh-pooh the tales of vimanas, ancient aerial wars, and the unleashing of weapons of mass destruction, there are reasons to pause and consider these historical accounts seriously.

The famous Iron Pillar is located near Delhi. At either 2,300 years old by the Puranic accounts of the Guptas or 1,500 years old by modern reckoning, it has been exposed to heat, rain, wind, and so forth for all this time and still has not rusted or decayed.

Such metal appears to have been scientifically engineered. Amulets made of similarly sophisticated metals have been found in association with five-thousand-year-old skeletons near Harappa. These skeletons have been found to have high levels of radioactivity, perhaps as the result of wars around the time of the Mahabharata.

Other physical evidence that supports the contention that there is far more to the ancient history of India than we know can be found in the Indus Valley civilization.

This civilization is much lesser known than its Egyptian or Mesopotamian counterparts, though it is every bit as mysterious; the Harappan cities in the Indus Valley are now in ruins that lie scattered across a thousand miles of desert terrain in northwestern India and eastern Pakistan.

These planned urban centers display a uniform pattern based on civil engineering principles that date back more than five thousand years. The cities, such as Mohenjo Daro, had two- and three-story houses, each with separate bathrooms, living rooms, and kitchens.

The houses had their own wells and indoor plumbing, outdoor drainage systems, even sit-down Western-style toilets that flushed into an underground sewage system via drains going to a septic tank.

Contrast these five-thousand-year-old cities to those of much of modern-day rural India and Pakistan, which still lack these civilized conveniences. In fact, urban planning is a recent development, even in the cities of Western Europe; how are we to understand cultural revolution in the context of this Indus Valley civilization that has lain in ruins for thousands of years?

We need to comprehend how the builders of this civilization created standardized bricks by the hundreds of millions, which were used to build the cities. Why were they so far advanced as to create uniform weights and measures? We also need to decipher their curious writing system, which remains one of the few completely unknown written languages in the world. We also ought to try to understand how the civilization came to an abrupt end.

The ruined ancient city of Dholavira has marble pillars, and the builders used stone architecture for its palace and an Athenian-like stadium, which included the world’s oldest signboard (dating to 2500 BCE). The city also boasts a large water reservoir cut from rock.

Fourteen field seasons of excavation through an enormous deposit caused by the successive settlements at the site for over 1500 years during all through the 3rd millennium and unto the middle of the 2nd millennium BC have revealed seven significant cultural stages documenting the rise and fall of the Indus civilization in addition to bringing to light a major, a model city which is remarkable for its exquisite planning, monumental structures, aesthetic architecture, amazing water harvesting system and a variety in funerary architecture.

The other area in which the Harappans of Dholavira excelled spectacularly pertained to water harvesting with the aid of dams, drains, reservoirs and storm water management, which eloquently speak of tremendous engineering skill of the builders. Equally important is the fact that all those features were integrated parts of city planning and were surely the beauty aids, too. The Harappans created about sixteen or more reservoir of varying sizes and designs and arranged them in a series practically on all four sides.

A cursory estimate indicates that the water structures and relevant and related activities accounts for 10 hectares of area, in other words 10% of the total area that the city appropriated within its outer fortification. The 13 m of gradient between high and low areas from east to west within the walls was ideally suited for creating cascading reservoirs which were separated from each other by enormous and broad bunds and yet connected through feeding drains.9

The above level of sophistication has not been duplicated in terms of urban planning and civil engineering in Asia to this day or, in fact, in most of the world. It shows a level of engineering knowledge and skills that is virtually impossible to account for, given that this is one of Earth’s first civilizations.

How was this level of advancement achieved and then so quickly forgotten by all of the other cultures of the Indian subcontinent?

Another Indus Valley city, Lothal, was recently excavated from February 13, 1955, to May 19, 1960, by the Archaeological Survey of India, the official Indian government agency for the preservation of ancient monuments. Lothal represents a very fresh site in archaeological terms.

The city’s dock, the world’s earliest known, connected the city to an ancient waterway, the Sabarmati River, which was on the trade route between Harappan cities in Sindh and the peninsula of Saurashtra when the surrounding Kutch district—now a desert—was a part of the Arabian Sea.

Lothal was a thriving trade center in ancient times. The city produced fine handmade beads, gems, and valuable ornaments, which reached the far corners of West Asia and Africa. The techniques and tools the city’s people pioneered for precision bead making and metallurgy have stood the test of time. In fact, such beads still cannot be duplicated by modern craftsmen.

The city planners and engineers engaged themselves to protect the area from consistent floods in the following ways: The town was divided into blocks of 1–2-metre-high (3–6 feet) platforms of sun dried bricks, each serving 20–30 houses of thick mud and brick walls. The city was divided into a citadel, or acropolis and a lower town.

The rulers of the town lived in the acropolis, which featured paved baths, underground and surface drains (built of kiln-fired bricks) and potable water well. The lower town was subdivided into two sectors. A north-south arterial street was the main commercial area. It was flanked by shops of rich and ordinary merchants and craftsman. The residential area was located to either side of the marketplace.10

In terms of managing the waterway, the dock was built on the eastern flank of the town, and it has become regarded by archaeologists as a great feat of civil engineering. It was located away from the main current of the river to avoid silting but provided access to ships in high tide as well. The warehouse was built close to the acropolis on a 3.5-meterhigh (10.5 feet) podium of mud bricks.

The rulers could thus supervise the activity on the dock and warehouse simultaneously. Facilitating the movement of cargo was a mud-brick wharf, 220 meters (720 feet) long, built on the western arm of the dock, with a ramp leading to the warehouse.

Though the Harappan civilization does not overwhelm us with massive buildings, its overall urban organization and the sophisticated civil engineering required to facilitate indoor plumbing, public baths, river diversion, dams, canals, and so forth are on par with the Great Pyramid in terms of being anomalous artifacts.

The uniform organization of the townships, which spanned a thousand miles, and their standardized social and economic institutions attest to the Harappans being an advanced and highly disciplined society with a common purpose. Apparently, commerce and administrative duties were performed according to uniform standards, supposedly a fairly modern invention.

Municipal administration was strict; the width of most streets remained the same over a long time period. No structures were allowed to deviate from the building codes. These regulations were enforced throughout all the cities of the entire thousand-mile area.

Householders possessed a sump and a collection chamber in which to deposit solid waste to prevent the clogging of city drains. Drains, manholes, and cesspools kept the city clean and deposited the waste in the river, which was washed out during high tide.

Lothal imported en masse raw materials like copper, chert, and semiprecious stones from Mohenjo Daro and Harappa. These raw materials would be fashioned into sophisticated ornaments, selas, and other valuables. Then they were shipped out to inner villages and towns.

Does all of this sound strangely out of synch with our view of ancient history and how human culture was supposed to have gradually evolved from the Stone Age? In fact, the Harappan cities were every bit as sophisticated as our own today, perhaps even more minutely planned. There is nothing haphazard about them.

Archaeologists have found evidence that the Harappans had trade relations with the ancient Sumerians, and it is peculiar that these two enigmatic civilizations sprang up at the same time. Also worth noting is the fact that the Harappans were a bronze culture, though they lacked deposits of copper and tin ore—bronze’s raw materials.

CONCLUSION

The ancient texts of India clearly describe flying machines and contact with extraterrestrial races having occurred when science tells us they should not have. Unlike the Old Testament and the Enumma Elish, the Indian texts directly portray the flight characteristics of these flying machines, the vimanas.

Last, the Indus Valley civilization, which built planned cities using modern-day civil engineering principles, stands as an anomaly that directly refutes the theories and time lines that cultural evolutionists currently propose.