Ferre Laevers

Profile

Laevers’ name is associated in the early childhood sector with well-being and involvement. Over the past 35 years he has been involved in international research on the experiential learning of young children and has produced practitioner tools to encourage and develop ‘deep learning’ in children.

Key dates

1994 – Published first book on young children’s learning

2005 – Co-founder and President of European Early Childhood Education Research Association

Links

- How Children Learn 1

Te Whariki: the New Zealand early years curriculum

- How Children Learn 3

Ferre Laevers

The care and education of children up to 3

- How Children Learn 4

Albert Bandura

Abraham Maslow

Carl Rogers

His life

Ferre (Ferdinand) Laevers was born in the Belgian Congo. His family returned to Belgium when he was ten. He eventually became a student in Leuven, about 30 kilometres east of Brussels. He developed an interest in early years education and how teachers could encourage self-direction amongst the children in their learning.

He took up a post in 1973 at Katholieke Universiteit in Leuven to support training and research in the early years. Amongst the influences on his thinking while undertaking his doctoral studies were Jean Piaget, Carl Rogers and Sir Herbert Read. (1)

Laevers began his work on experiential learning in 1976 when he was involved in a project to help a group of Flemish early years teachers to critically reflect on their practice. Over the years he has been part of similar projects in over 20 countries.

At the time of writing, Laevers is Director of the Research Centre for Experiential Education and was elected president of the European Early Childhood Education Research Association (EECERA) in 2005.

His writing

Laevers has authored or co-authored over 100 articles, reports, chapters and books since 1996. The vast majority relate to his research on the well-being of children and their involvement in learning. The full list of his publications can be found at <https://lirias.kuleuven.be/cv?u=U0018384>.

His theory

Laevers considers the learning process to consist of three distinct elements:

The inputs consist of the ‘ingredients for a powerful learning environment’ (2), including:

- Respect for the child.

- Communication, a positive group climate.

- A rich environment.

- An open framework approach.

- Representation: impression-expression cycle.

- Observation, observation, observation.

The outcomes, or the effects of learning, are:

- Emotional health/self-esteem.

- Exploratory drive.

- Competencies and life skills.

- The basic attitude of ‘linkedness’ (3) i.e. be able to:

- Empathise.

- Value others.

- Take responsibility.

- Instigate positive action.

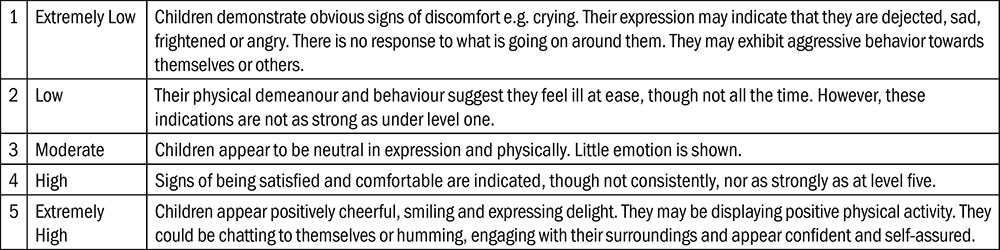

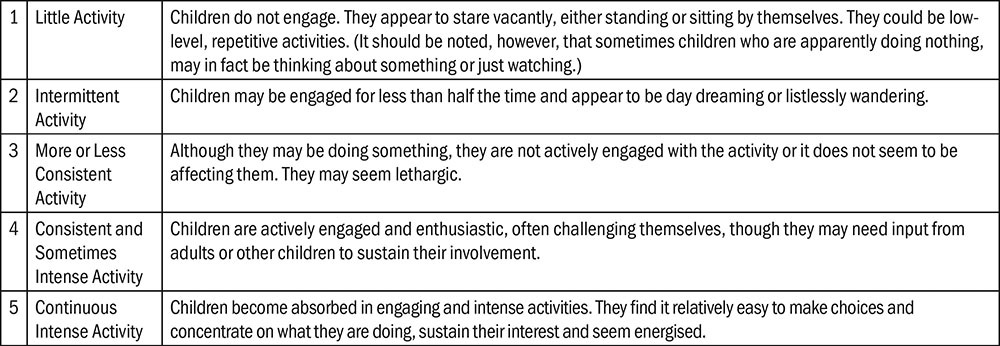

In order to explore the processes involved in the learning experience, Laevers has identified two sets of indicators which he feels should be considered in the planning of any educational setting. These relate to emotional well-being and involvement. His university has given its name to the Leuven Scales, which indicate the levels at which the learner is functioning. Laevers’ ideas suggest that high levels of well-being and involvement are indicative of high levels of children’s development and deep learning which should lead to a much greater capacity to deal with work, relationships and general aspects of life.

Children are observed for regular short periods of time and scored using the scales. It is felt that, unless they are operating at levels four or five, they will not be benefiting fully from their activities in terms of their learning. It is recognised however that children are unlikely to be functioning at the higher levels consistently. After an initial analysis, the observer will then focus on the children who are scoring at low levels and design appropriately targeted, individual interventions.

The Leuven Scales can be used as a quality improvement tool. The scales highlight the importance of looking more broadly at process and achievement in children’s learning, rather than focusing on their outcomes. (4) As well as providing diagnostic information on the processes involved in the children’s learning, the observations also provide useful feedback to the adults who are designing and providing the learning context.

The Leuven Scale for Well-being (2)

The Leuven Scale for Involvement (2)

Putting the theory into practice

The ideas embodied in well-being and involvement have been honed over the years by extensive international research. The experiences of those involved have resulted in an ‘inventory of initiatives’ that promote well-being and involvement. This can be used by practitioners who wish to improve the development of learning within their settings.

This inventory is called ‘The Ten Action Points’: (5)

- Re-arrange the classroom into appealing corners or areas.

- Check the content of the corners and replace unattractive materials with more appealing ones.

- Introduce new and unconventional materials and activities.

- Observe children, discover their interests and find activities that meet these orientations.

- Support ongoing activities through stimulating impulses and enriching interventions.

- Widen the possibilities for free initiative and support them with sound rules and agreements.

- Explore the relation with each of the children and between children and try to improve it.

- Introduce activities that help children to explore the world of behaviour, feelings and values.

- Identify children with emotional problems and work out sustaining interventions.

- Identify children with developmental needs and work out interventions that engender involvement within the problem area.

His influence

There has been a great deal of interest in Laevers’ work internationally. In the UK he has influenced the direction of The Effective Early Learning Project, led by Christine Pascal and Tony Bertram. Pascal and Bertram say that in the United States research on motivation (which demonstrates Involvement) has shown that children with high levels of motivation perform better on outcome measures of performance, such as decoding and comprehension skills. (6)

Although the application of ‘The Ten Action Points’ can benefit all children, the final two points relate specifically to children with special needs. Point nine deals with behavioural and emotional problems. Based on a large body of international research, the expanded action point provides suggestions for an experiential strategy to support children by structuring time and space, or by giving positive attention. For example, a child who demands a lot of attention through negative behaviour can be targeted for unexpected praise when they behave in the desired way. Point 10 relates to children with developmental needs and involves specific interventions relating to children’s ‘problem areas’. For example, a child who finds it difficult to coordinate sight and movement can be encouraged to engage in appropriate catching activities.

Laevers’ work on children’s well-being has been used to inform the 2007 UNICEF study of children’s well-being (7), as well as Ofsted’s publication of a comparative table of aspects of children’s well-being for Local Authorities in England, as part of the Annual Performance Assessment of Local Authorities. (8)

Comment

Some schools in the UK have adopted the Leuven Scale of Wellbeing to identify barriers to learning for their pupils. Performance data on children measures a very narrow range of achievements (e.g. SATs) and schools feel that the Leuven Scale data contextualises this and provides indications for personalised interventions for children.

Part of the appeal of the Leuven Scales is that, in the modern context of data-rich schools and settings, they provide more numerical data on children which can be used to analyse correlations and compare groups or individuals. However, it could be argued that the numbers lose the essential qualities that descriptive or ‘best fit’ assessments can provide.

The observations which underpin the scales essentially relate to how the individual child functions within their learning environment. The Leuven Scales do not address, what humanistic psychologists such as Bandura and Maslow have recognised, the importance of social interactions on development.

References

- Pascal, C. (2005). ‘Down to Experience’. [Internet]. Available from: <http://www.nurseryworld.co.uk/news/713346/Down-experience/?DCMP=ILC-SEARCH>.

- Lewis, K. (2011) Ferre Laevers emotional well being and involvement scales [Internet]. Available from: <www.earlylearninghq.org.uk/earlylearninghq-blog/the-leuven-well-being-and-involvement-scales>.

- Laevers, F. (2003) Making care and education more effective through well-being and involvement in Laevers, F. & Heylen, L. (Ed) (2003) Involvement of Children and Teacher Style: Insights from an International Study on Experiential Education. Leuven University Press.

- Allen, S. Whalley, M. (2010) Supporting Pedagogy and Practice in Early Years Settings. Learning Matters.

- Laevers, F. (2008) The Project Experiential Education: Concepts and experiences at the level of context, process and outcome. [Internet]. Available from: <www.european-agency.org/agency-projects/assessment-resource-guide/documents/2008/11/Laevers.pdf/view>.

- Pascal, C. Bertram, T. (1997) Effective Early Learning: Case Studies in Improvement, Effective Early Learning Research Project. Paul Chapman.

- UNICEF (2007) Child poverty in perspective: An overview of child well-being in rich countries [Internet]. Available from: <www.unicef.org/media/files/ChildPovertyReport.pdf>.

- (2009) Children’s wellbeing in England. [Internet]. Available from: <www.guardian.co.uk/education/table/2009/jan/07/children-wellbeing-england-ofsted?INTCMP=SRCH>.

Where to find out more

Collins, J. Foley, P. ed. (2008) Promoting Children’s Wellbeing: Policy and Practice. Policy Press.

http://www.teachingexpertise.com/articles/project-improves-practice-1121

http://www.earlylearninghq.org.uk/earlylearninghq-blog/the-leuven-well-being-and-involvement-scales/