The Desperate Struggle for Fleetwood Hill

CHAPTER EIGHT

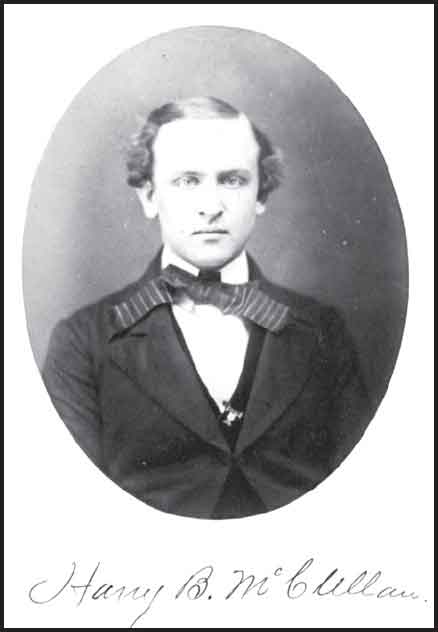

Stuart’s adjutant, Maj. Henry B. McClellan, was standing on Fleetwood Hill a few minutes before 11:30. A newcomer to Stuart’s staff, McClellan was a native Philadelphian who had attended Williams College and, after graduating, settled in Cumberland County, Virginia. He was working as a schoolteacher when war broke out in 1861 and stuck with his adopted state, although four of his brothers served in the Union army, as did his first cousin, Union Maj. Gen. George McClellan.

Major McClellan had just heard the report of Robertson’s breathless couriers when Gregg’s column appeared before him, headed toward Brandy Station.

“They were pressing steadily toward the railroad station,” McClellan recalled. “How could they be prevented from also occupying the Fleetwood Hill, the key to the whole position? Matters looked serious!”

The prominent hill, which dominated the landscape and was only occupied by a few other orderlies, lay open to the Federal assault.

Nearby, however, a 12-pound Napoleon of Capt. Roger P. Chew’s Battery, commanded by Lt. John W. “Tuck” Carter, was resupplying its ammunition. Reacting swiftly, McClellan ordered Carter to open on the Yankees while “courier after courier was dispatched to General Stuart to inform him of the peril.”

“The Yankees are at Brandy!” yelled the riders as they raced up to Stuart at St. James Church. Immediately, Stuart dispatched the 12th Virginia Cavalry and the 35th Battalion of Virginia Cavalry of Jones’ brigade to go to McClellan. “Go for Hampton,” Stuart said to one of his staff officers, “Tell him to come. For God’s sake, bring Hampton.”

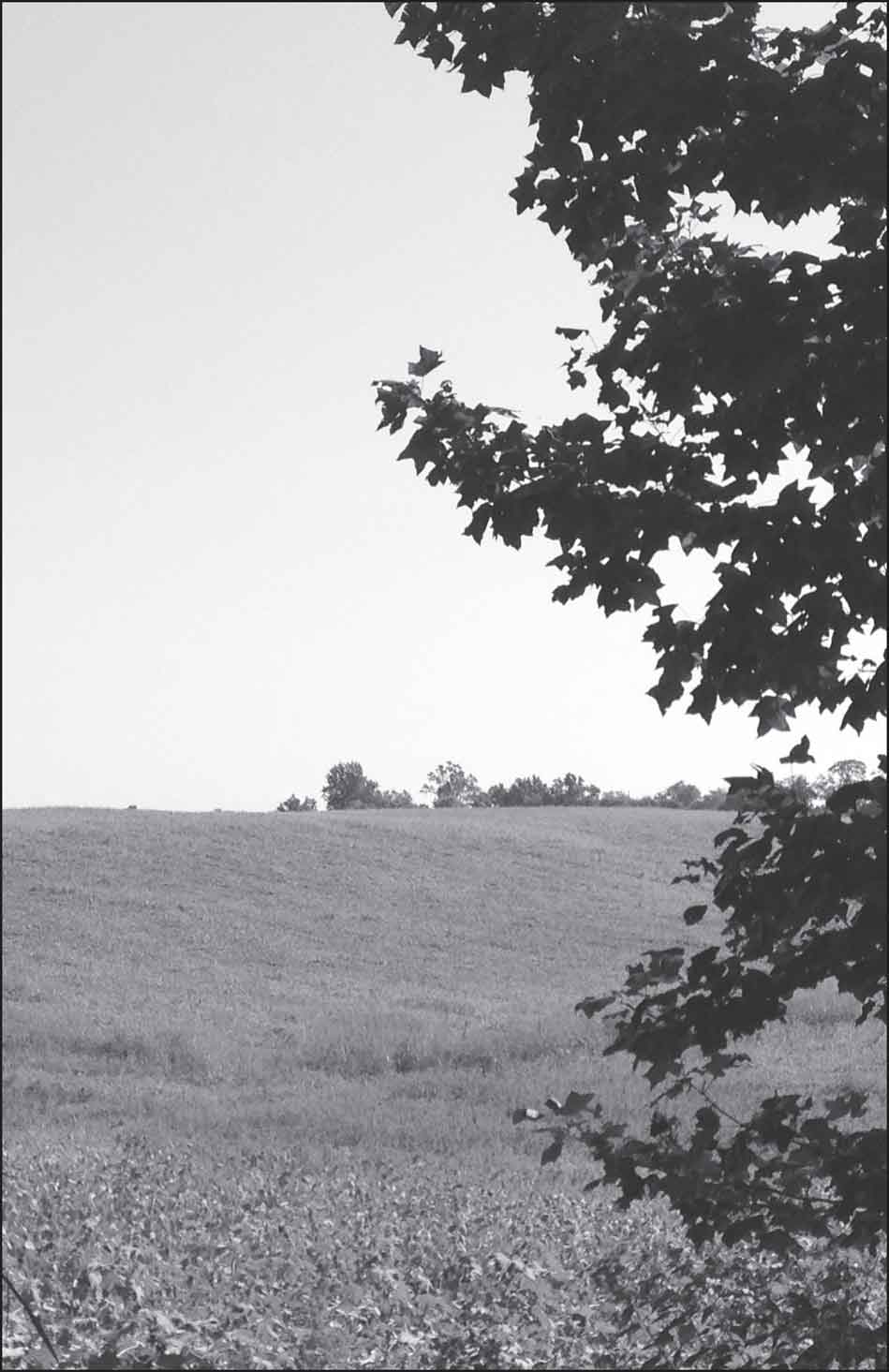

FLEETWOOD HILL—The arrival of Brig. Gen. David Gregg’s troopers in Brandy Station presented a severe threat to Stuart’s lines at St. James Church. In peril, Stuart rushed men to defend Fleetwood Hill, the rear of his position. This resulted in a heavy see-saw melee across the heights. Stuart was able to hold on and repulse Gregg’s attack.

Leaving his skirmishers as well as Rooney Lee’s brigade to contend with Buford, Stuart pulled Jones’ brigade and Hart’s battery out of line and dashed to Fleetwood Hill.

Stuart’s order reached Hampton, whose brigade began galloping to McClellan’s aid with the Cobb Legion Cavalry in the lead. One Confederate staff officer fondly recalled, “No more brilliant spectacle was ever witnessed than the brave Hampton leading on his gallant Carolinians.”

Henry McClellan was in this area atop Fleetwood Hill when he spotted David Gregg’s division arriving in Brandy Station. (dd)

Gregg’s troopers neared the crest of the hill just as the Confederate horsemen reached the scene. “There now followed a passage of arms filled with romantic interest and splendor to a degree unequaled by anything our war produced,” wrote a Confederate. Elements from Jones’ brigade collided with the 1st New Jersey of Col. Sir Percy Wyndham’s brigade, with the Federals eventually gaining the upper hand. Then the Confederates counterattacked.

A soldier in the 12th Virginia remembered, “Round and round it went; we would break their line on one side, and they would break ours on the other … it was pell mell, helter skelter—a yankee and there a rebel—killing, wounding, and taking prisoners.” Another Virginian wrote, “we fought them singlehanded, by twos, fours, and by squads, just as the circumstances permitted.”

Hammered by the enemy counterattack, the stubborn 1st New Jersey still held onto the hill. Surrounded by the Confederates, the Jerseymen had to hack their way. “The fighting was hand to hand and of the most desperate kind,” a lieutenant in the regiment, Thomas Cox, wrote. The 1st New Jersey lost their commander, Lt. Col. Virgil Brodrick, and his second in command, Maj. John H. Shelmire. One Union officer recalled, “Col. Brodrick fought like a lion. Wherever the fight was the fiercest his voice could be heard cheering on his men, and his revolver and sabre dealing death.” Mortally wounded, Broderick was left behind and captured. He died in enemy hands.

During the ensuing retreat, the Federals lost another officer. Colonel Wyndham went down with a severe leg wound. Choosing to remain with his brigade for the time being, he was eventually forced to leave the field.

Lt. Col. Virgil Broderick led the 1st New Jersey into the fight on Fleetwood Hill. It would be his last battle. (usahec)

As the battle swirled around them on Fleetwood Hill, Capt. Joseph Martin’s 6th New York Independent Battery deployed to support the troopers along the southwest slope. Martin’s guns proved to be an enticing target for Maj. Cabell Flournoy, who ordered his 6th Virginia to draw sabers and charge. One of the Virginians wrote that Martin’s men “were the bravest cannoneers that ever followed a gun … we shot their men and horses down, they would fight us with their swabs, with but few of them left.” A counterattack eventually forced Flournoy’s command back.

A soldier of the 1st Pennsylvania recalled the “heavy crash of the meeting columns, and next the clash of sabers.” Then came the “rattle of pistol and carbine, mingling with the frenzied imprecation, the wild shriek that follows the death blow, the demand to surrender, and the appeal for mercy, forming the horrid din of battle.” One North Carolinian vividly remembered that “the whole plain was covered with men and horses, charging in all directions … with banners flying, sabers glittering, and the fierce flash of firearms, amid the din, dust, and smoke of battle … such scenes cannot last beyond a few fearful minutes.” A Georgian who witnessed the battle wrote, “Thousands of flashing sabers streamed in the sunlight … the surging ranks swayed up and down the sides of Fleetwood Hill … dense clouds of smoke and dust rose as a curtain to cover the tumultuous and bloody scene.”

Maj. Henry McClellan played a critical role in notifying Stuart of the threat to the rear of his lines, thus securing Fleetwood Hill. (wc)

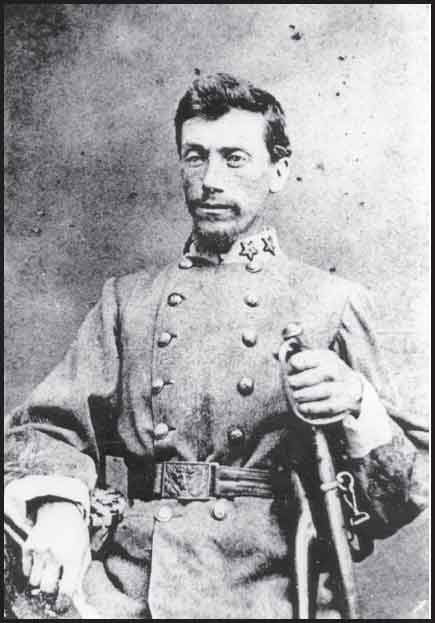

Martin’s guns launched shell after shell into the Confederate ranks. Their fire grew to be too much for Lt. Col. Elijah V. White, who commanded the 35th Virginia Battalion. His troopers were known for their ferocity in battle, which later earned them the sobriquet “Comanches.” White turned to his men and ordered them to charge. “With never a halt or a falter the battalion dashed on, scattering the supports and capturing the battery after a desperate fight, in which the artillerymen fought like heroes, with small arms, long after their guns were silenced,” recorded the unit’s historian.

General Lee observed part of the battle from the Beauregard house. When the charge of the 1st Maine Cavalry nearly reached the home, Second Corps commander Richard Ewell suggested the Confederate high command could “gather into the house and defend it to the last.” (cm)

Some of the Comanches tried to turn the captured guns on the Yankees. The Federals, however, were girding for a counterattack. Two companies of the 1st Maryland Cavalry advanced, forcing White to withdraw. This small melee left most of the battery’s horses dead, forcing the pieces to be moved off the field by hand.

Lt. Col. Elijah White’s regiment was involved in one of the better-known episodes of the battle: They charged down Fleetwood Hill to attack the 6th New York Independent Battery. Although they temporarily captured the pieces, an enemy counterattack forced White to withdraw. (loc)

While White and the 1st Maryland struggled below him, Stuart received support in the form of batteries commanded by Capts. William McGregor and Roger Chew. One of the artillerists recalled that the fighting was “fearful … we … made it so warm for their cavalry, they brought two batteries to play on us.”

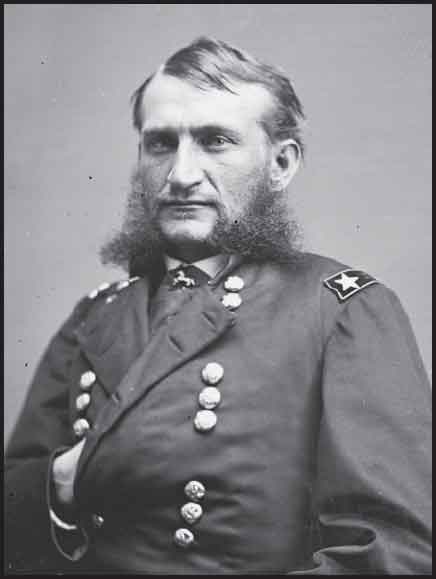

This additional artillery fire prompted Gregg to commit Judson Kilpatrick’s brigade to the fight. Kilpatrick in turn ordered the 10th New York Cavalry to draw sabers and charge. “The rebel line that swept down on us came in splendid order,” a member of the regiment wrote, “and when the two lines were about to close in, they opened a rapid fire.” What occurred next was “an indescribable clashing and slashing, banging and yelling … we were … fighting desperately to maintain the position.”

Brigadier General Wade Hampton’s charging horsemen crashed into the 10th New York. Stuart, following along nearby, yelled to the men as they entered the fight, “Give them the sabre, boys!”

Lieutenant Colonel Will Delony of the Cobb Legion remembered, “We moved up at a gallop our Regt in the advance and the enemy ran up two guns on our left flank & we were ordered to charge…. I was in the head of the Regt … off we went in fine style.” With Delony leading one column and their colonel, Pierce M. B. Young, leading another, the Georgians crashed into the Federals. “The day was ours in less time than I can tell it,” Deloney wrote. “We pursued them until called off. With the Jeff Davis Legion & one Squadron of the 1st S. C. Regt we drove off the support of their guns.”

A New Jerseyan and West Point graduate, Col. Judson Kilpatrick was the first Regular Army officer wounded during the war at the battle of Big Bethel. (loc)

Colonel John L. Black’s 1st South Carolina Cavalry slammed into the 2nd New York Cavalry. The commander of the New Yorkers, Lt. Col. Henry E. Davies, wrote, “By reason of an order improperly given, as is alleged, the head of the column was turned to the left, and proceeded some distance down the railroad.” There the South Carolinians struck them. During the ensuing fight, Davies had his horse shot out from under him and received a nasty saber cut that nearly severed his belt but barely missed his body.

The 2nd New York scattered and fled, with Black’s regiment storming after them “cutting down the fugitives without mercy.” When another of Hampton’s regiments threatened their flank, the Empire Staters skedaddled. Kilpatrick, who had previously commanded this regiment and expected a lot from his old command, was furious at their rout.

Attempting to rally his men, Kilpatrick called to the 1st Maine Cavalry—“Men of Maine! You must save the day! Follow me!”—and personally led a charge by the Maine troopers. “The order was received like an electric shock,” remembered a Maine officer. “One idea seemed conveyed to every man throughout those squadrons: This is our opportunity come at last! A spirit of emulation seized them.” A magnificent sight unfolded as the Maine men charged. One observer thought, “It was a scene to be witnessed but once in a lifetime.”

Wade Hampton’s brigade charged across ground inside the tree line in their assault to retain possession of Fleetwood Hill. (dd)

Their determined charge crashed into the Confederates and saved the Federal guns near Fleetwood Hill.

One of Gregg’s staff officers attempted to gain assistance in protecting Martin’s cannons. Spotting Kilpatrick, he galloped over and asked for help. “To hell with them!” responded Kilpatrick. “Let Gregg look out for his own guns.” Shocked, the staffer repeated his request. “No! Damned if I will!” was the reply.

Lieutenant Colonel Charles H. Smith of the 1st Maine ordered some of his men to dismount and fight on foot. One of Smith’s officers recalled that he “looked and acted as cool as though on dress parade. As soon as he had rallied his scattered men, he remounted the regiment, formed squadrons and moved directly toward those guns which the enemy had by this time succeeded in loading, and were just in the act of training on the regiment.” Just as the Confederate gunners were about to pull the lanyards, Smith turned the column to the right, narrowly avoiding the artillery fire. Smith then gave the order “Fours left into line!” and charged toward the Barbour house.

At one point during the fight, Kilpatrick squared off with one of his old comrades from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. The two had never liked each other and the war deepened their hatred. The Southerner spotted Kilpatrick, drew his pistol, fired, and missed. “Little Kil,” as he was known, drew his saber, and the two officers fenced. “Both men fought like tigers at bay,” remembered one soldier who witnessed the duel. Kilpatrick received a slight cut on the arm and slashed back, his injured opponent reeling in the saddle. He then slashed again, killing the Confederate. Riding away, he proclaimed, “That rights a wrong. I have wanted to meet him ever since the war commenced.”

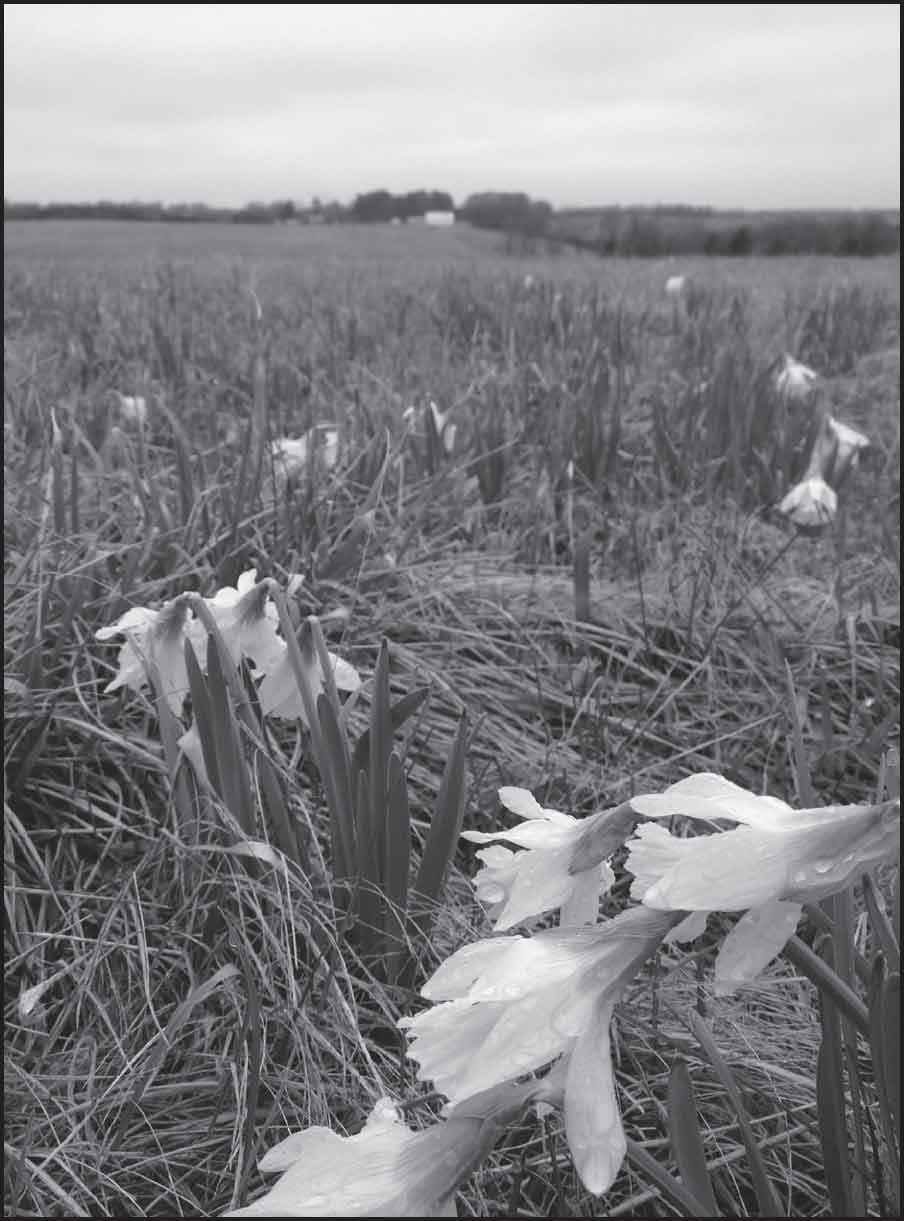

Looking south from the Confederate position atop Fleetwood Hill toward Brandy Station (cm)

The success of Kilpatrick’s attack was short lived. As one of Hampton’s troopers recalled, “The tide of battle alternated.” The Jeff Davis Legion, of Hampton’s brigade, attacked east of the railroad tracks, supported by Grumble Jones’ hard-fighting regiments. The “fierce struggle” shoved Gregg’s division back.

Hampton’s troopers bore down on them. Unfortunately, the South Carolinian was unable to drive home the assault. Stuart had ordered two of the South Carolinian’s regiments to remain on Fleetwood Hill, so Hampton ordered an assault without his full command. Afterwards, he bitterly complained, “No notice of this disposition of half of my brigade by General Stuart had been given to me by that officer, and I found myself deprived of two of my regiments at the very moment they could have reaped the fruits of the victory.” Fuming, Hampton watched Gregg withdraw from the field unhindered.

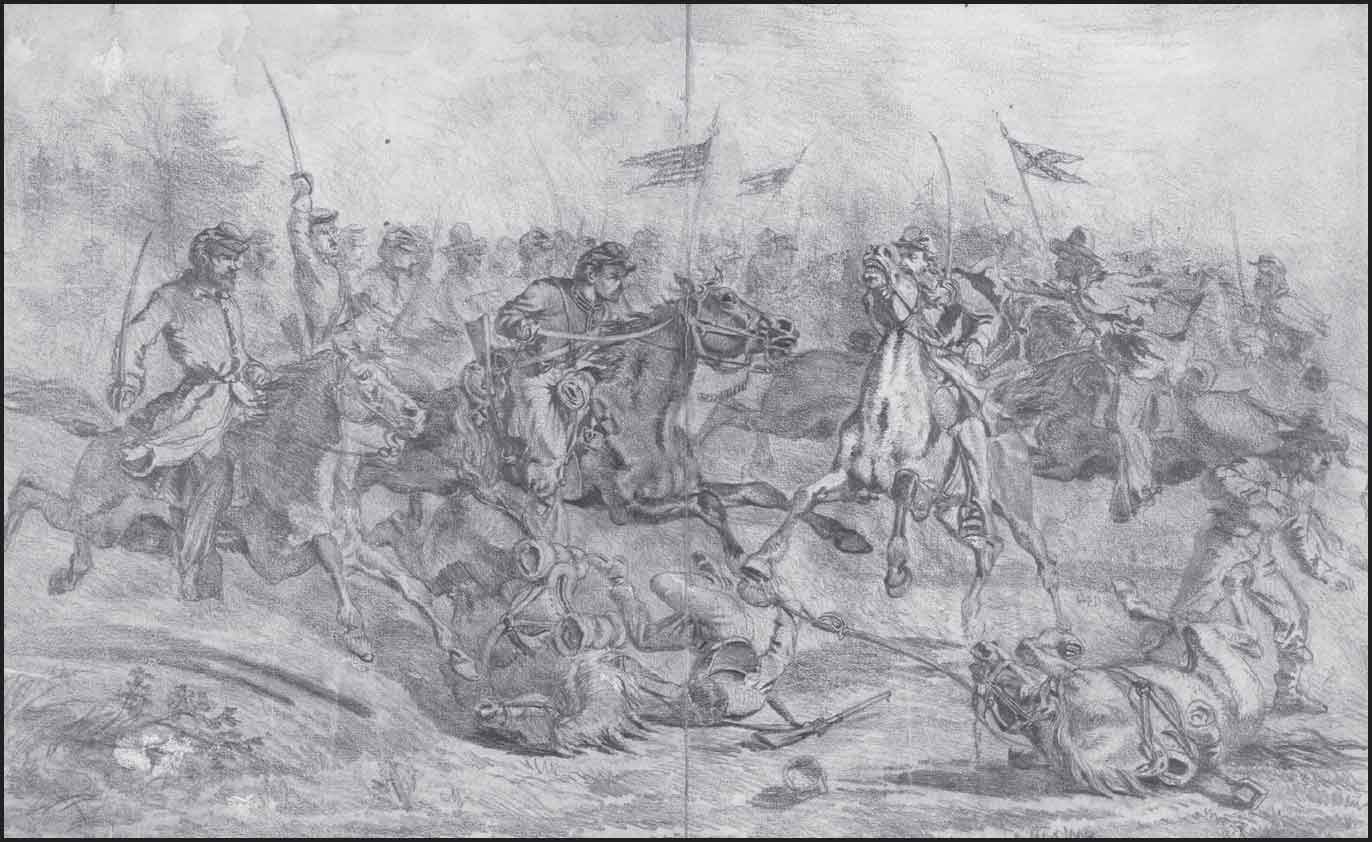

Artist Edwin Forbes drew this sketch of the battle of Brandy Station. The mounted fighting was typical of that which occurred for Fleetwood Hill. (loc)

The Federals, however, had left a section of Lt. Wade Wilson’s battery of horse artillery about 100 yards north of the railroad tracks. Kilpatrick had ordered Wilson to limber up and follow the rest of the column. Before they could do so, Col. Lunsford L. Lomax’s 11th Virginia Cavalry pounced on them “like a whirlwind.” Crashing into the guns, Lomax’s men engaged the dismounted troopers who were supporting Wilson. These dismounted cavalrymen held off the Rebels long enough for the artillerists to carry their guns off to safety. Chasing down the Union troopers, one man remembered, “Lomax and the men of the bloody Eleventh were among them, slashing left and right.”

Diverging from the artillerists, Lomax then attacked Wyndam’s brigade near the railroad. Lomax remembered, “I charged, and drove them from the station.” Advancing toward Culpeper, Lomax sent a detachment toward the village and then toward Stevensburg before finally rejoining Stuart.

A company of the 10th New York also lingered behind because the order to withdraw never reached them. A Confederate charge finally chased them off. Fortunately, they escaped without sustaining any casualties.

From his headquarters on Fleetwood Hill, Stuart watched as Gregg withdrew. With desperate fighting, Stuart parried a major threat to the rear of his line. “Thus ended the attack of Gregg’s division upon the Fleetwood Hill,” Major McClellan noted. “Modern warfare cannot furnish an instance of a field more closely, more valiantly contested. General Gregg retired from the field defeated, but defiant and unwilling to acknowledge a defeat.”

After two hours of ferocious hand-to-hand fighting, Gregg reformed his command in the fields to the south of Brandy Station. Unsupported, Gregg wrote later, “I ordered the withdrawal of my brigades. In good order they left the field, the enemy choosing not to follow.”

At Fleetwood Hill

You are now standing atop Fleetwood Hill. This is the epicenter of the Brandy Station battlefield. Immediately to your left is where Jeb Stuart’s headquarters was located. The United Daughters of the Confederacy monument was erected in 1926 to mark the spot and commemorate the battle on property eventually acquired by the Civil War Trust in 2014, which installed the trail and the interpretive markers. If you wish to walk the short loop, keep to your right to follow the action chronologically.

At the crest of the ridge to your right is the area where Major McClellan spotted Gregg’s division riding into Brandy Station, which is across Route 15/29 and directly behind you. It was here that Lieutenant Tucker engaged the Federals. Fortuitously, the 12th Virginia Cavalry arrived at the crest as Carter expended his last rounds. By then, the Yankees had nearly reached them.

The U.D.C. monument is the only historical monument on the battlefield. (cm)

Here, the Virginians engaged the leading Union regiment, the veteran 1st New Jersey Cavalry. Major Hugh Janeway of the 1st New Jersey remembered that his troopers “rode up the gentle ascent that led to Stuart’s headquarters, the men gripping hard their sabers, and the horses taking ravines and ditches in their stride.” The Jerseymen briefly gained the crest but were swept away by the attacking Confederates moments later. A Rebel artillerist recalled, “The two forces met with a crash that could have been heard miles away … back and forth they swayed across the slope of Fleetwood Hill.” Remembered Maj. Myron Beaumont of the 1st New Jersey:

The enemy had withdrawn behind the crest of the hill, and it was not until we were within a hundred yards of the top that they advanced to meet us. They were armed, principally, with pistols and carbines, our men using generally the saber. Then began the most spirited and hardest fought cavalry fight ever known in this country.

With the help of Civil War Trails and under the direction of historian Clark “Bud” Hall, the Civil War Trust has interpreted the crest of Fleetwood Hill. (dd)

The 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry also joined the contest. A Pennsylvania officer wrote afterwards,

Scarcely half the regiment had gotten into position, when the enemy opened a battery … from the eminence of the Barbour house … when we moved forward it was to storm the position … as we marched straight toward the smoking cannons’ mounts, they first saluted us with spherical case, and as the distance grew less, hurled grape and canister into our faces.

As you follow the trail, the Barbour house, also known as Beauregard, is the large brick house across the field on the ridge to your right. Late in the battle, Gen. Robert E. Lee came forward from his camps around Culpeper and observed the closing phases from the front porch of Beauregard. The pond at the base of the ridge was not there in 1863.

Wade Hampton and Judson Kilpatrick started a fued on this field at Brandy Station that would last all the way to Bennett Place, N.C., in April of 1865. (cm)

Arriving to reinforce their fellow Virginians was the hard-fighting 6th Virginia. The engagement continued to sway over the hillside. This combat was so desperate and confusing that one man from the 12th Virginia remembered that he was captured—and escaped—twice as his regiment engaged the Northerners. The 1st New Jersey lost 56 of the 280 men through the course of the three-hour contest.

In the area of tour stop 6, at the base of Fleetwood Hill, Captain Martin deployed a section of his guns. The 6th Virginia made the first attempt to capture them. Lieutenant Robert O. Allen, who had killed Grimes Davis earlier that morning, was severely wounded in the shoulder in this assault. After the repulse of the 6th Virginia, Lt. Col. Elijah White’s 35th Battalion of Virginia Cavalry attacked Martin’s guns on an axis that followed the route of Fleetwood Heights Road. Martin remembered that “of the 36 men that I took into the engagement, but 6 came out safely, and of these 30, 21 are either killed, wounded, or missing, and scarcely one of them will but carry the honorable mark of the saber or bullet to his grave.”

As you pass the gazebo, the area between it and the modern highway is where Hampton’s brigade engaged the 2nd and 10th New York from Col. Judson Kilpatrick’s brigade. Hampton personally led the assault against the 10th New York. Colonel Pierce M. B. Young, who commanded the Cobb Legion of Hampton’s brigade, remembered that his men “swept the hill clear of the enemy, he being scattered and entirely routed.” Young’s men received the personal compliments of Jeb Stuart, who rode up to them and declared, “Cobb’s Legion, you’ve covered yourselves with glory.”

Looking southward from Fleetwood’s hilltop. (cm)

Later in the action, the 1st Maine Cavalry charged directly toward where you are standing and across the face of Fleetwood Hill. Finally reaching the vicinity of Beauregard, the unsupported regiment was forced to ride through the fighting to reach the safety of the Union lines.

Wesley Merritt’s Federal cavalry moved across Yew Ridge from left to right to strike Rooney Lee’s horsemen. (cm)