The early days of flight were full of challenges. Airplanes were dangerous, and many men and women lost their lives while aviation was still developing. However, some people faced the more basic challenge of simply being allowed to fly. Though the early 20th century was focused on the future of technology, in many ways society was still stuck in the past when it came to judging people based on skin color.

While Amelia Earhart was able to earn a U.S. pilot's license in 1921, Bessie Coleman was unable to do so because she was an African-American woman.

Coleman did not let this prejudice stop her. In 1920, after finding out that she could qualify for an aviation license in France, Coleman learned to speak French and traveled to Paris. On June 15, 1921, Bessie Coleman became the first African-American woman to earn a pilot's license.

Even after Coleman received her license, no one in the U.S. would give her additional lessons. Not discouraged, Coleman trained in Europe and returned to America as a stunt pilot. Stunt pilots use their planes to perform exciting tricks in the air.

Coleman, or "Queen Bess" as she was often called, was a media darling. Her shows were wildly popular. She was even offered a role in a movie, which she later turned down because she disapproved of the content. Tragically, at the height of her popularity in 1926, Coleman was a passenger in a fatal plane crash. Her death was a shock, and a reminder of the bravery of early aviators. They risked their lives every time they stepped in an airplane, but continued to pursue their dreams of flight.

Coleman's determination was an inspiration to many people, including a woman named Willa Brown.

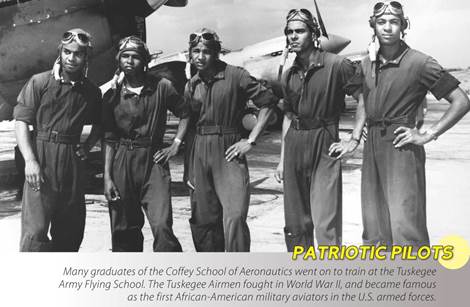

In 1938, one year after Amelia Earhart's plane vanished, Brown made history. She became the first African-American woman to earn a private pilot's license in the U.S. Brown and her husband, flight instructor Cornelius R. Coffey, wanted to improve opportunities for black pilots in the U.S. Together, they founded the Coffey School of Aeronautics in Illinois, and worked with the government to prepare African-American pilots for the military.

Before her death in 1992 at the age of 86, Brown broke many boundaries. She became the first African-American woman to hold a commercial U.S. pilot's license in addition to a private license, and the first African-American woman to become an officer in the Civil Air Patrol. During her lifetime, Brown worked tirelessly to prove that the bravery, determination, and intelligence needed to control an aircraft can arrive in any gender or color.

The fight for flying equality was carried on by women like Beverly Burns. In 1974, Burns was a flight attendant for American Airlines when the words of one man changed her life. She was waiting between flights at an airport, chatting with a pilot. He told Burns why he thought there weren't many female commercial pilots: "Women are just not smart enough to do this job."

Burns later described how his words affected her: "I knew as soon as the words came out of his mouth, 'women cannot be pilots,' that I wanted to be an airline captain immediately."

By the 1970s, flying by commercial airplane was becoming the norm. Though the demand for commercial airline pilots was rising, only a few of them were women. A 2013 study showed that only five percent of all commercial pilots in the U.S. and Canada were women. This number is low for many reasons. Most commercial pilots come from a military background, but women were not allowed to fly fighter jets until 1993. In fact, American Airlines was the first major commercial airline to hire a woman pilot in 1973.

Burns fought, not only to prove one man wrong, but because she loved flying and wanted to rise to the top of her field. She earned her commercial pilot's license, and became one of the best. Among her accomplishments, Burns was the first woman to captain a Boeing 747 jumbo jet. Since a 747 can hold more than 400 passengers, during each flight Burns literally held hundreds of lives in her hands. When she retired in 2008, Burns had been a captain for 27 years, and clocked more than twenty-five thousand hours of flight time.