After adventurers took to the skies, they decided to keep going and aim for the stars. Though humanity has dreamed of space travel for centuries, it wasn't until the 1960s that our technology finally caught up with our imaginations. In 1961, a Russian man named Lt. Yuri Gagarin was the first person launched into space. In 1969, Neil Armstrong spoke these famous words when he became the first person to set foot on the moon: "One small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind." In his speech, Armstrong used the word "mankind" to mean people in general, not just men. This is important to remember, because women, too, fought to travel beyond the limits of our world.

Geraldyn "Jerrie" Cobb was the first woman to pass all of the tests necessary to become an astronaut. Born in 1931, the daughter of a pilot, Cobb was a natural in the air. She earned her private pilot's license when she was just 17 years old, and her commercial license a year later.

At age 21, though she was not in the military, Cobb helped transport military fighter planes from Miami to Columbia for the Peruvian Air Force. Being a woman, Cobb was not the transport company's first choice for the job. However, many male pilots were not willing to fly the dangerous trip over mountains and across the water. Cobb jumped at the chance to prove that she had the skill and bravery needed to do the job. Though things did not always go smoothly while flying to South America, Cobb was a success, and eventually became the chief pilot for the company's South American operations.

In 1959, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was in the process of selecting astronauts for the Mercury space mission. Though they were not actually considering women for space flight at that time, they wanted to see how women would hold up to the difficult tests that every astronaut had to pass. When she was approached by NASA to take these tests, Cobb was a manager for Aero Design and Engineering Company, and had a record-setting career as a pilot. Among other awards, Cobb had received the Amelia Earhart Gold Medal of Achievement in 1949, and was named Pilot of the Year by the National Pilots Association in 1959. Cobb gladly volunteered to undergo NASA's testing, wanting to prove that women, like men, were fit for space travel.

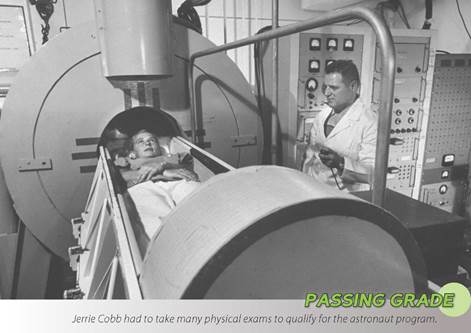

Out of the 25 women selected for testing, Cobb was the only one who passed every round. She experienced physical and mental exams that pushed her beyond what most people can endure.

For example, they tested Cobb's physical stamina by making her perform exercises, like riding a stationary bike, until she couldn't pedal anymore. A few of the stranger tests included electric shocks to check reflexes, ice water shots to the inner ear to find out how quickly a person could recover from being dizzy, and swallowing a three-foot rubber tube to test her stomach acid. They also had Cobb go through long periods of isolation, to see how she would hold up to the loneliness of being in space.

After passing all the exams, Cobb asked the government to let qualifying women train with men for space travel. However, at that time, NASA would only allow people who had military flight experience into their space program. In 1959, women were not allowed to fly in the military, and thus were not eligible for space travel. Many people thought that an exception should be made for Cobb—whose 10,000 flight hours was more than double that of some qualifying male astronauts.

Unfortunately, since those were not military hours, the government did not budge.

Jerrie Cobb never did travel into space, though such a journey always remained her dream. She continued to fly, and even won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1981 for flying medical supplies to struggling parts of the world, and for exploring new air routes.

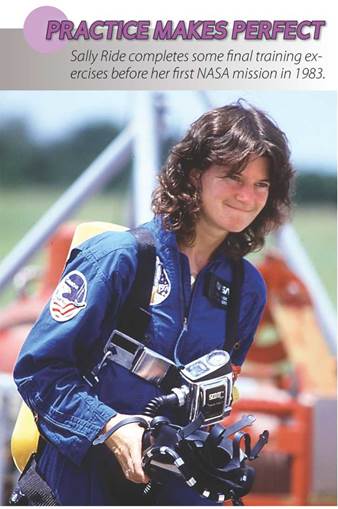

Many women have benefited from Cobb's tireless efforts to promote equality in the space program. In 1983, Sally Ride became the first woman from the U.S. to travel into space. Growing up, Ride's parents encouraged her and her sister to pursue anything they were interested in, even if those interests weren't typically for girls. In an interview, Ride's mother said that she and her husband "simply forgot to tell them that there were things they couldn't do." As a child, Ride was always the best at sports, beating other kids, boys and girls, at football and baseball. As she got older, Ride balanced athletics with academics. She was a tennis champion, and earned a PhD in physics from Stanford University.

In 1978, Ride saw an ad in the Stanford newspaper for the NASA Space Program. Ride jumped at the chance to become an astronaut. Like Cobb before her, Ride passed all of NASA's tests. After a year-long training program, Ride became eligible for space travel.

Before becoming the first American woman in space, Ride worked for NASA for several years. Among other accomplishments, Ride helped NASA develop a robotic arm for the space shuttle. When

NASA announced that Ride would be the first American woman to travel into space, many people in the media questioned how a woman would handle such stressful conditions. During an interview before the launch, some people even asked Ride if she would cry if something went wrong.

Ride patiently answered their rude questions, saying that she did not think of herself as a woman who was about to make history, but as an astronaut doing her job.

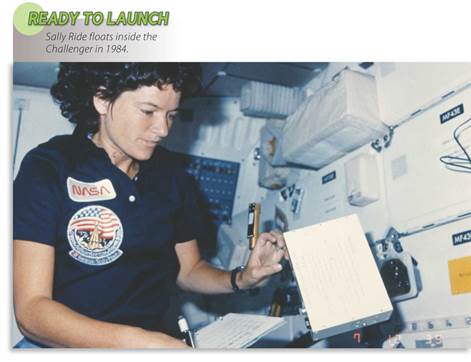

During her career as an astronaut, Ride went on two successful launches on the space shuttle Challenger, first in 1983, then in1984. She was not just along for the ride, but was an important member of the crew.

For example, one of her duties was operating the robotic arm that she had helped design. She was the first woman to retrieve a satellite with a robotic arm.

In her lifetime, Ride was inducted into the Astronaut Hall of Fame, the National Women's Hall of Fame, and was twice awarded the NASA Space Flight Medal. Ride always said that she owed a great debt to the women who came before her, who had fought so hard for equality.

To help future generations, Ride developed educational programs that encouraged children, particularly girls, to learn about science. After her death in 2012, Sally Ride was given the Space Foundations' highest possible honor: the General James E. Hill Lifetime Space Achievement Award.