CHAPTER 4

The Substantive Characteristics of Securities*

Types of Securities for Analytic Purposes

Control versus Non-Control Securities

Control and Non-Control Pricing and Arbitrage

Terms of Securities as Options

What a Security Is Depends on Where You Sit

In his 1938 book, The Theory of Investment Value (Harvard University Press), John Burr Williams stated that “investment value [is] the present worth of the future dividends in the case of a common stock, or of the future coupons and principal in the case of a bond” (p. 6). Williams was right on the money in describing the investment value of a performing loan, whether a bond, a trade credit, or a lease. For that definition to be functional, however, the investment value of a common stock has to contain many more elements than the present worth of future dividends. Thus, Williams’s definition ought to be restated: investment value is the present worth of future cash bailouts, whatever their source.

There are several forms of cash bailouts:

- Contractually assured payments by issuers to creditors in the forms of interest payments, principal repayments, and premiums for performing loans.

- Dividends to holders of equity securities, and repurchases of equity securities by issuers.

- Sale of securities to a market by an OPMI, whether an outside passive minority investor (OPMI) market or a control market (e.g., a merger and acquisition ([M&A] market).

- Other people’s money (OPM), which allows borrowing without disposing of the underlying security.

- The present value of benefits from control or elements of control that might exist because of securities ownership.

- Favorable tax attributes that might be created out of ownership of certain flow-through securities (e.g., a limited partnership interest in a tax shelter [TS]).

Since these bailouts attach to different types of securities, it is instructive to conceptually define the different types of securities for our analytic purposes.

TYPES OF SECURITIES FOR ANALYTIC PURPOSES

For analytic purposes, there are five types of securities:

CONTROL VERSUS NON-CONTROL SECURITIES

Probably the most important thing to understand in examining the substantive characteristics of securities is that control common stock is essentially a different commodity from OPMI common stock. Even though they are exactly the same in form most of the time and OPMI common can be converted into control (or elements of control) common, and vice versa, the differences between control common and OPMI common are far more important than the similarities:

- They tend to trade in different markets at different prices.

- They tend to be analyzed differently.

- They tend to be bought and sold by different, largely unrelated constituencies.

- The different constituencies seek different returns on the investment. Most OPMIs seem to seek to maximize total return mostly by sale to an OPMI market in the relatively short run; they seem to be influenced by daily changes in market prices. Most control buyers seek something off the top (SOTT), tax shelter (TS), the use of other people’s money (OPM), entrenchment, and sale to another control market, or partial cash out in an initial public offering (IPO). Most control buyers are not heavily influenced by day-to-day price swings in OPMI markets unless they are actually attempting to buy, sell, or borrow against their securities positions.

- Corporate law—especially state law court decisions in leading corporate states, and federal bankruptcy law—is designed to entrench control groups and managements in office at the expense of OPMI rights. In small part, securities laws, as embodied in the amended Securities Act of 1933 and the amended Securities and Exchange Act of 1934, also have the effect of delivering management entrenchment at the expense of OPMI shareholders. Three such regulatory areas entrenching management are securities’ regulations governing cash tender offers, exchange offers, and proxy solicitations.

- The bulk of U.S. securities laws, especially as embodied in the various acts administered by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), are designed to and do protect OPMIs. One of the areas of protection is against several forms of overreaching by control people through provision of:

- Orderly trading markets

- Disclosures

- Oversight of fiduciaries and quasi-fiduciaries, including those who control public corporations.

CONTROL AND NON-CONTROL PRICING AND ARBITRAGE

Much of the substantive differences between control pricing and OPMI pricing are resolved through long-term arbitrages, which are the very essence of the tendency toward efficiency that exists in all markets, specifically between and among disparate markets. There are times when OPMI market prices are super-high compared with what businesses would be worth as private concerns. In that case, new shares are marketed publicly in IPOs and in secondary underwritings and M&A in which newly issued common shares, valued at or near OPMI market prices, are part or all of the consideration paid for an acquisition. At other times, OPMI market prices might be quite low compared with prevailing prices in control markets. Then, there is a tendency for cheap shares to be acquired for cash and debt, in M&A transactions, in hostile takeovers, and in the particular form of M&A called leveraged buyouts (LBOs), management buyouts (MBOs), or going-privates.

There are built-in limitations to this tendency toward long-term arbitrages. OPMI stock markets tend to be rather capricious, and certain sections of OPMI markets tend to be even more volatile than others. One extremely volatile section is the IPO market. The ability to sell IPOs can be vigorously proscribed at times (as was the case from 1991 to 1993, in the fall of 1998 and in 2008–2009), although as is pointed out in Chapter 14’s discussion of promoters’ and professionals’ compensations, the financial community has a vested interest in encouraging IPOs.

As for a control group’s buying up common stocks from OPMIs, there are three key factors that often ameliorate this tendency toward efficiency. First, the businesses involved have to be reasonably well financed, have access to credit markets in order to whet the interest of most financial (nonstrategic control buyers), or both. Second, the entrenchment of incumbent management is frequently a showstopper preventing any real efficiencies from arising in the market for changes in control. Outsiders seeking control from entrenched managements usually have to incur huge up-front expenses and almost always are faced with uncertainty as to whether control will be attainable. Finally, any process involving changes of control entails considerable administration (i.e., deal) expenses for attorneys, investment bankers, accountants, tax advisers, and others.

In a very meaningful sense, nonperforming loans are much like common stock even though there probably are less dramatic price differences here between OPMI markets and control markets. In the case of nonperforming loans, obtaining elements of control usually refers to getting influence over the reorganization process for a troubled company rather than to getting control of a business. Control over reorganization is key for creditors, whether the company restructures out of court or in Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

As to control of operations, the tendency seems to be that there is almost as much management entrenchment in troubled public companies as in healthy companies. Corporate governance provisions are an important part of virtually all Chapter 11 plans of reorganization. Also, in dealing with nonperforming loans, loan governance provisions become crucially important, especially for out-of-court reorganizations. The key loan governance player for bank loans tends to be the agent bank. For publicly traded bonds, the indenture trustee—almost always the corporate trust department of a large commercial bank—is important.

In terms of corporate governance, management entrenchment provisions are now well nigh universal. In general, though, it is far harder, with public companies, to remove a general partner of a limited partnership than to remove the management of a corporation. Usual management entrenchment devices, both corporate and limited partnership, include one or more of the following:

- Limited voting for OPMI common

- Staggered board

- Supermajorities

- Poison pills

- Parachutes

- Reincorporation in management-friendly states, such as Pennsylvania or Indiana

- Blank check preferred stocks

- A lack of stockholder rights to call special meetings

Outside passive minority investor market prices, whenever they exist, always deserve weight in any analysis. How much depends on the objectives of the investor and the characteristics of the investment; weight might range from as high as 100 percent to as low as 2 percent. Market price deserves 100 percent weight when an OPMI has as a solitary goal the risk-adjusted maximization of total return consistently (consistently means all the time). It may deserve 100 percent weight also when a money manager’s job depends on stock-market performance, where the money manager/analyst knows little or nothing about the company in whose securities he or she is investing, or where the portfolio is fully financed with borrowed money. Finally, OPMI market prices probably deserve 100 percent weight or close to it in option trading and risk-arbitrage situations (i.e., such events as publicly announced mergers in which there will be relatively determinant workouts in relatively determinant periods of time). In all other instances, OPMI market prices deserve considerably less than 100 percent weight.

Most of the 100 percent situations involve trading by short-run–oriented speculators. When other conditions are introduced—for example, the investor, operating without borrowed funds, emphasizes contractually assured cash income rather than total return as an investment objective; the investor focuses on long-term buy-and-hold; or the analysis of a security involves great complexity (e.g., most common stocks)—weight to OPMI market prices in the analytic mix has to be reduced.

OPMI market prices are often a lot less important in the analysis of most performing loans than of non-arbitrage common stocks because:

| Years to Maturity | Price (%) | |

| 10 | 75.42 | |

| 9 | 76.90 | |

| 8 | 78.66 | |

| 7 | 80.53 | |

| 6 | 82.58 | |

| 5 | 84.84 | |

| 4 | 87.32 | |

| 3 | 93.06 | |

| 2 | 96.36 | |

| 1 | 100.00 |

For spread lenders OPMI market prices probably deserve considerable weight, though probably not as great as the spread between interest received and interest paid. Recent changes in Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) requiring portfolios to be marked to market, however, elevate the importance of OPMI market prices because accounting data, as reported and unadjusted, become important for regulatory or credit rating purposes. For those who carry performing loans on margin, OPMI market prices may deserve close to 100 percent weight.

TERMS OF SECURITIES AS OPTIONS

Loans made at interest rates greater than the risk-free rate of money are substantively equivalent to credit insurance and put options. The extra interest rate is equal to insurance premiums paid to the lender for taking credit risks. The extra interest can also be viewed as having the lender sell a put option. The lender collects a premium for the right to put to the borrower, or require the borrower to buy, certain assets in certain events.

EXAMPLE

In January 1996, Third Avenue Value Fund entered into a put agreement with Heller Financial for one year. The fund sold Heller the put for a 7 percent fee. The terms of the arrangement were that in the event Kmart filed for Chapter 11 relief in the next 12 months, Heller had the right to require the fund buy 100 percent of the principal amount of Kmart payables owned by Heller for 87 percent. This transaction actually went forward as a loan. The fund acquired from Heller for 80 percent cash a one-year medium-term note bearing interest at Libor plus 10 basis points (bips). If Kmart filed for Chapter 11 within the year, Heller could satisfy the note at its option by delivering to the fund either 87 percent cash or 100 percent in Kmart payables. If Kmart did not file, the note would be satisfied by payment of 87 percent cash to the fund.

Yield-to-maturity is an artificial calculation except for zero-coupon bonds, in that it assumes cash received over the life of the loan will always be reinvested at the original rates of return. Yield-to-maturity is an essential tool, however, for comparative analysis, comparing the theoretical returns available between and among different credit issues. It is the annual return to be earned on a performing loan over its life. The yield has two components where a loan is priced at some price other than the payment to be made at maturity. The first component is the interest rate. The second component is either the amortization of discount if the bond was acquired at a discount from the amount to be paid at maturity or the amortization of premium if the price is in excess of the principal amount to be paid at maturity.

Any term of a security ought to be viewed as an option, or privilege, granted to an issuer or as an obligation imposed on an issuer or a holder. Here is a breakdown of the status of various securities terms:

- Call feature: An option to the issuer.

- Mandatory redemption: An obligation of the issuer.

- Cash dividend: Once it is declared, the recipient is obligated to receive it. Before declared, an option of the issuer.

- Stock buyback: Any individual shareholder has the option of selling or not selling. The company has the option of putting a share repurchase program in place.

- Cash tender offer or exchange offer: Individual security holder has the option to accept or not accept it.

- Merger or use of proxy machinery: If the requisite vote is obtained, it is subject only to perfecting dissenter rights (which is hard to do); every security holder is obligated to participate.

- Change of terms of a loan agreement regarding cash payments outside Chapter 11: Each individual debt holder has the option of going along.

- Change of any other term of a loan agreement outside of Chapter 11: If the requisite vote is obtained, all debt holders have to go along.

WHAT A SECURITY IS DEPENDS ON WHERE YOU SIT

In reality, there are few rigid definitions of a security’s classification; what a security is depends on where you sit. Subordinated debentures are a good example of a security that ought to have more than one definition. From the vantage point of the common stock, subordinated debentures are debt. From the vantage point of senior lenders, however, to whom the subordinates are expressly junior (that is what subordination means), the subordinates are part of the borrowing base, akin to equity. Another example would be preferred stock issued by a subsidiary where the parent company’s sole asset is the common stock of the subsidiary. The parent company’s principal source of cash would be dividends paid on the subsidiary’s common stock. Payment of the subsidiary’s common stock dividends requires prior dividend payments to the subsidiary preferred stock. The proceeds of payments on subsidiary common stock are used to service parent-company bank loans. Thus, absent any other covenants (such as the subsidiary’s assets’ being pledged to parent-company banks), the preferred stock of the subsidiary has a senior position vis-à-vis bank borrowings by the parent. In the consolidated financial statements of the company prepared in accordance with GAAP, however, the subsidiary’s preferred stock appears to be junior to the parent company’s bank debt.

EXAMPLE

Back in 1990, Ambase’s principal subsidiary was the Home Insurance Company. Ambase owned 100 percent of the outstanding common stock of Home Insurance Company, and it was dividends on Home Insurance common stock that gave Ambase most of its wherewithal to service Ambase bank debt. Home Insurance Company 14¼ percent preferred was, in all meaningful respects, senior to the borrowings from banks by parent company Ambase.

In certain academic circles, it has been argued that little justification exists for issuing preferred stocks rather than subordinated debentures. The reasoning is that interest payable by the corporation on subordinated debentures is tax deductible, but dividend payments on the preferred stock are not tax deductible. In the real world, there are myriad reasons justifying the issuance of and the existence of preferred stocks; here are a few:

- Qualified domestic corporations that receive dividends from less-than-80 percent-owned domestic corporations can exclude from income 70 percent of such dividends received under Section 243 of the Internal Revenue Code. As a practical matter, the combined tax bills of the two corporations may be smaller when the security issued is a preferred stock rather than a subordinated debenture.

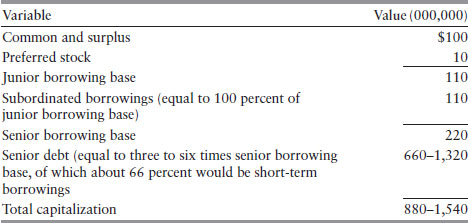

- Many—if not most—corporations have layer-cake capitalizations, and the issuance of preferred stock enables such corporations to issue considerably more senior debt than would otherwise be the case. For example, a typical finance company holding consumer receivables might have the capitalization, shown from the bottom up here:

- Assume the company can incur senior debt of four times its borrowing base. Without preferred stock being issued, such senior debt would amount to $800 million. With preferred stock outstanding, the senior debt issuable would amount to $880 million. In other words, the issuance of $10 million of preferred stock would allow the company to increase its senior borrowing by $80 million.

- Voting preferred stocks are an essential tool for tax-free exchanges in connection with mergers that qualify as reorganizations under Section 368(b) and (c) of the Internal Revenue Code. By use of preferred stocks and common stocks, it becomes feasible to satisfy the various needs and desires of disparate parties to the merger transaction:

- Those who desire to maximize long-term total return and control would receive common stock and/or super-voting-rights common stock.

- Those who desire cash income, relative seniority, or both, as well as something of an equity kicker, would receive convertible preferred stock.

- There frequently are regulatory and rating agency reasons for issuing preferreds rather than subordinates.

Preferred rights are spelled out in certificates of designation, which are part of a corporation’s articles of incorporation. Privately negotiated terms of preferred stocks can have quite meaningful protections for holders; whereas protections for publicly traded preferreds tend to be sparse. The most meaningful protection for publicly issued preferred stock seems to be one requiring a two-thirds vote of the outstanding preferred class if the company is to issue a new preferred stock equal or senior to the existing issue as to dividends or liquidation. The right usually given to the preferred to elect two directors if six quarterly dividends are missed is normally not much of a right at all, since the typical preferred holder has no special access to the corporate proxy machinery or to the corporate treasury to finance a proxy solicitation. An important right for preferred stocks that usually does not exist is the right to vote separately as a class on all matters.

In the case of troubled companies, preferred stocks frequently are in better positions, de facto, than subordinates. Subordinates have rights to accelerate if an event of default occurs and is continuing. Given the subordinates’ junior position in the capitalization, this right is often the right to commit suicide. The preferred, on the other hand, piles up dividend arrearages and might be in a better position to make reorganization deals.

In pricing convertible and other hybrid securities, there are a few simple computer-programmable variables resulting in a normal convertible curve:

- Yield

- Yield-to-maturity

- Percent premium over conversion parity

- Percent premium (discount) from call

- Beta of the underlying common stock

In a market tending toward instantaneous efficiency for new issues, convertibles might be offered at prices equal to 150 to 250 basis points below comparable credits in terms of yield-to-maturity and at 25 percent to 45 percent premiums over conversion parity compared with the prices at which the underlying common stock trades.

There are trade-offs in comparing straight debt characteristics with convertibles. A shorter maturity and strong mandatory redemption requirements tend to be more valuable for a holder of straight debt, provided the debt does not trade at a premium over call price. Early maturity, early redemption, or the presence of both qualities diminishes the value of conversion privileges. For any convertible or option, long life tends to be a highly favorable characteristic. Any convertible feature is translatable into an option feature.

Alienability refers to factors that cause a security to have a fair value different from an OPMI market price. In general, there are four alienability factors:

Alienability discounts for restriction and blockage can run from 15 to 50 percent of OPMI market prices. It is hard to put a percentage number on control premiums, however; they will vary case by case.

Securities Act restrictions on resale can exist for securities not registered under the Securities Act of 1933. The restraint against public resale can be engendered by one of two conditions: the holder is an insider or the securities were never registered. Sales can be made in OPMI markets, however, pursuant to Rule 144 or a Section 4(a) exemption.

Securities Act restrictions on resale have become considerably less onerous over the years as Rule 144 has been liberalized. Presently, restricted shares held fully paid for at least six months can be resold to the OPMI market without restriction other than the public information requirement. After one year, unlimited sales into OPMI markets are allowed without any restriction. A holder of restricted stock may obtain rights of registration of the piggyback, the trigger variety, or both.

Many insiders have incentives to have low OPMI market prices and thus have inherent conflicts of interest with short-run OPMI speculators. Such incentives include:

- Estate valuation purposes: The lower the OPMI market price, the less the value of the estate either at the date of death or six months thereafter.

- Going private: The lower the OPMI price, the less insiders will have to pay in a going-private transaction.

Control insiders have basic advantages over OPMIs in that the insiders control the timing of events. For example, those control people who seek to go private can wait for a bear market in OPMI prices. The fairness of going-private transactions will always be measured in part by premiums paid over current OPMI market prices.

The concept of dilution is never absolute. It is always relative to something: (1) OPMI price, (2) underlying values, or (3) percentage of capitalization owned.

In examining securities from the point of view of corporate feasibility, the central necessity is to be aware that a security issued by a company has to deliver one of two things to a holder: either the right to receive from the company cash payments sooner or later, or ownership interest in the company, present or potential.

The rights to receive cash payments from the company that attach to debt instruments and preferred stocks can constitute a cash drain on a business and thus detract from creditworthiness. Ownership interests—common stocks, warrants, and options—do not require cash service from the company, although such securities might not have much value to a holder unless they held promise of a cash bailout by prospects of sale to a market or of delivering control benefits to the holder.

Issuing ownership securities that do not require cash service (i.e., dividends) can detract from corporate creditworthiness insofar as the existence of non–dividend-paying equities detracts from a company’s ability to access capital markets to sell new issues of equity. In the past, this has been a factor causing electric utilities and many finance companies to follow policies of paying out 60 to 80 percent of net income as dividends. For the vast majority of companies, though, dividend policy seems to have little or no impact on their ability to obtain access to capital markets. Indeed, for high-tech companies perceived as growth vehicles, the payment of regular dividends may be looked at as a negative factor, detracting from growth, in OPMI markets.

The fact that any security has to deliver either cash pay or ownership can become quite important in the structuring of appropriate capitalizations in resource conversion contexts, as in both LBOs and the reorganization of troubled companies. The appropriate capitalization ought to be feasible—not too heavy on cash-payment instruments. Also, appropriate instruments have to be issued to participants in the capitalization. Banks and life insurance companies will desire cash-payment instruments with seniority and strong covenants. Control buyers could want ownership instruments because those instruments deliver elements of control, especially when these participants do not need cash-payment instruments to service the debt they may have incurred in their own entities. OPMIs and other non-control investors could want ownership instruments because those instruments have promise of delivering a cash bailout by sale to a market.

SUMMARY

The investment value of a marketable security is the present worth of its cash bailouts whatever their source. We show many sources of cash bailouts that are outside of the radar screen of conventional approaches to security analysis. We also show that control common stocks, while identical in form to OPMI common stock, are a totally different commodity, and the pricing between these two otherwise identical securities is resolved in long-term arbitrages. For analytical purposes we classify securities into five broad groups: performing credit instruments, non-performing credit instruments, control securities, OPMI securities, and hybrids. Although our classification is useful for analytical purposes, what a security really is depends on where you sit.

* This chapter is based on material contained in Chapter 6 of Value Investing by Martin J. Whitman (© 1999 by Martin J. Whitman). This material is reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.